Table of Contents

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

- Value traps are stocks that look cheap but end up delivering poor returns.

- The main reasons why stocks end up being value traps include hoarding cash, having obsolescent products, selling commodity products in a market with excess supply, related party transactions, aggressive accounting, industry cyclicality, high debt and government interference.

- Cash hoarding is the most common in East Asian market such as Japan and South Korea, while in emerging Asia, the issue is more often complex corporate structure where the owner abuses minorities.

- But in any case, I suggest going through my list to make sure all risk are considered.

Here’s a lighter post with some of the lessons learnt over the past fifteen or so years I’ve been involved in Asian equities.

I’ll give you eight suggestions on how you can avoid “value traps”: situations where you think the stock is undervalued, yet ends up delivering sub-par returns.

The most obvious case of a value trap is when the company does not deliver any capital returns. But there are many other reasons why a stock might end up being a value trap, including outright fraud, aggressive accounting, industry cyclicality and more.

Table of contents:

1. Avoid the cash hoarders

2. Avoid shrinking-demand products

3. Avoid commodity products

4. Avoid complex corporate structures

5. Avoid aggressive accounting

6. Avoid cyclicals at peak margins

7. Avoid highly indebted companies

8. Avoid government interference

9. Conclusion1. Avoid the cash hoarders

Some businesses are capital intensive, and others are not. That’s fine.

But what’s inexcusable if a company reinvests capital at a low rate of return. Companies with poor capital allocation often end up being value traps.

In early 2024, I personally invested in IMAX Corporation’s Greater China subsidiary IMAX China (1970 HK — US$351 million). I felt it was an asymmetric bet on a takeover by the parent, since Chairman Richard Gelfond had expressed an interest in privatizing it. At the time I invested, minorities had already rejected a privatization bid of HK$10/share. The company would be allowed to make a new bid from 10 October 2024 onwards, just a few months after I invested.

However, the bid never came. And without a dividend, cash simply builds up on the balance sheet. And so despite a strong Chinese box office earlier this year, the stock continues to be range-bound. I personally think that the stock is undervalued. It trades at 10.7x P/E. But without a dividend, there is no value anchor. In such situations, investors can end up with a low internal rate of return, at least if a bid never materializes.

A more positive example is that of Koshidaka Holdings (2157 JP — US$801 million). It’s run by an entrepreneur called Hiroshi Koshidaka, who built it from the ground up. While Koshidaka’s dividend has always been low, the company has reinvested capital successfully through a larger network of karaoke outlets. It’s also been very successful in carving out a niche for itself. In 2020, Koshidaka spun off its sister company Curves to unlock value for shareholders. And the results speak for themselves, with a return on equity of 21%.

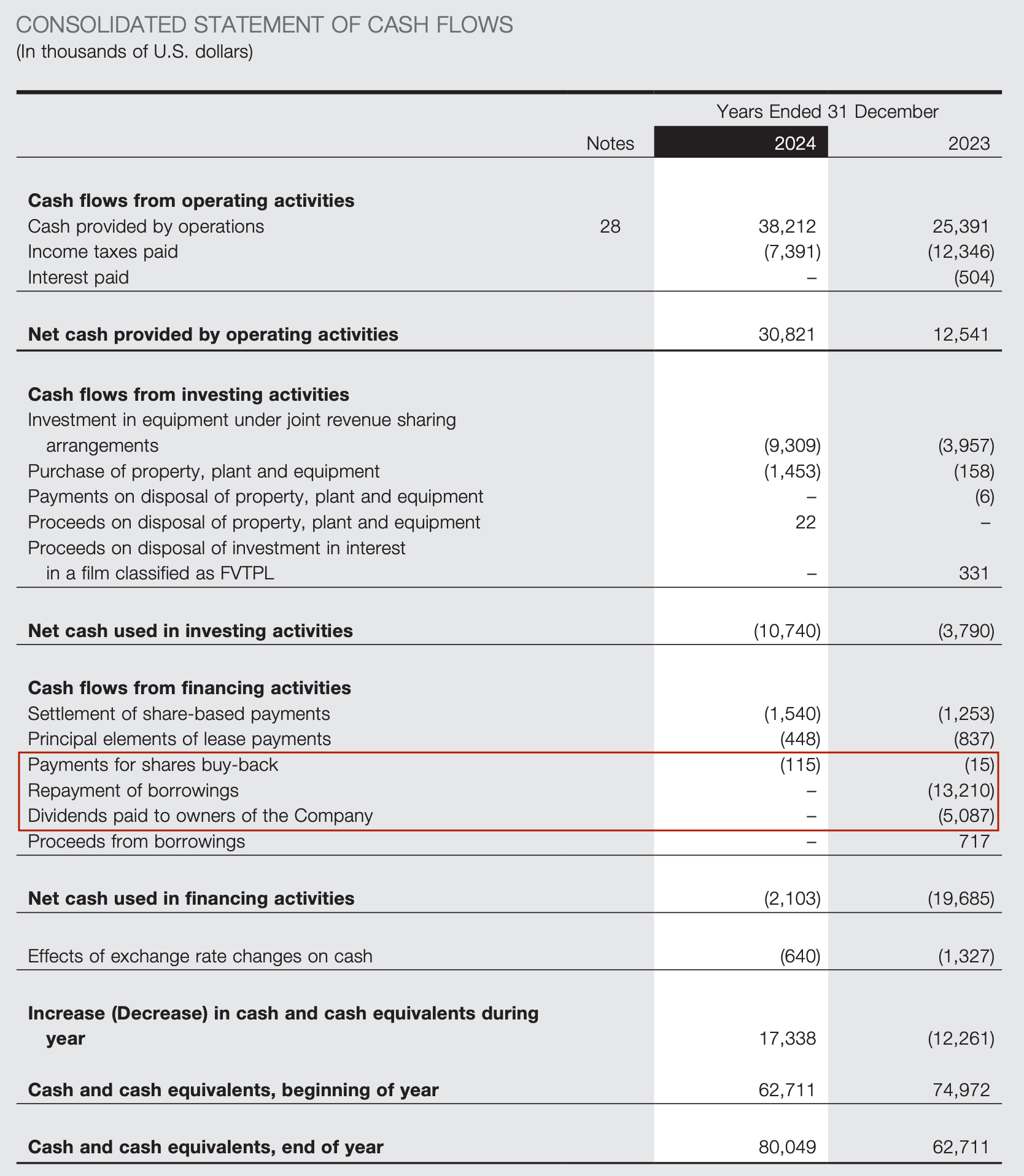

So, how do you avoid the value traps that simply do not return cash to shareholders? Check the company’s cash flow statement.

In IMAX China’s case, you can see that they pulled the dividend in 2023 and spent almost nothing on share buybacks in 2024. So US$17 million of cash built up on the balance sheet, unfortunately out of reach for us minority shareholders.

You can also look at the return on equity the company has achieved compared to its peers. If a CEO has done well, then the return on equity should be on its way to exceed that of the company’s sector peers. In IMAX China’s case, the return on equity is currently 12%, but that number will probably head lower the longer the dividend is omitted.

2. Avoid shrinking-demand products

To avoid value traps, you also need to invest in companies that are seeing growing demand for their products.

Companies selling fax machines, printers or other obsolescent products are not going to provide much earnings growth, and the dividend stream will likely shrink as well.

One good example is British American Tobacco (BAT) Malaysia (ROTH MK — US$352 million):

In 2015, the Malaysian government doubled its cigarette excise taxes. Coinciding with this rise was the start of the smuggling of illegal cigarettes from Indonesia. Such illegal cigarettes continue to take market share. And while the government has lost excise tax revenues, it still hasn’t responded.

Another problem for BAT Malaysia is the import of cheap vaping devices from China, further chipping away from BAT Malaysia’s cigarette monopoly. Since 2015, its earnings have declined by roughly 80% and indeed become a value trap.

In contrast, the demand for Samyang Food’s (003230 KS — US$8.3 billion) instant ramen is off-the-charts. I wrote about Samyang Foods in September 2024:

In the last financial year, the company’s earnings per share more than doubled, and the stock price has responded positively :

So what happened to Samyang Foods? Well, they have an ultra-spicy instant noodle product called Buldak Ramen that’s taking the world by storm. The product is now available across most major supermarkets in the US and Europe. Cardi B did a video doing the “Buldak Ramen” challenge on TikTok, trying to see whether she could take the spiciness level.

So how can you know whether the underlying demand for a product is rising or not? First, check the like-for-like volume numbers reported by the company. Second, observe consumer behavior through customer engagement metrics. Third, check alternative data sources such as Google Trends or Similarweb to see whether interest in the product is rising or falling.

You can also think long and hard about which new products are satisfying customers in a better or cheaper way. In Malaysia’s cigarette market, vaping devices are clearly superior in terms of cost. And when it comes to instant noodles, Buldak Ramen has carved out a nice niche for itself.

3. Avoid commodity products

With commodity products, you run the risk that excess supply will eat away at your margins and ultimately cause you to become loss-making. So products need some type of differentiation that will cause customers to stick with them.

One of my biggest losses over the past few years was investing in Chinese electric bicycle designer and manufacturer Niu (NIU US — US$336 million):

I thought the designs of the motorbikes were compelling, and that lithium-ion battery bikes would take market share from lead-acid battery bikes. Niu’s CEO Yan Li seems to have a sharp mind. Finally, I believed that the end of China’s COVID-19 lockdowns would cause foot traffic to return to Niu’s stores.

But in reality, demand never came back for Niu’s motorcycles. Why? Because competition with China’s Yageo and Aima caused prices to go lower and lower. Niu has now been forced to support its dealers through greater incentives, causing great losses. The crux of the issue is that while Niu’s designs have been beautiful, electric bikes are easy to produce, and there are no switching costs from one brand to another. They’re simply commodities.

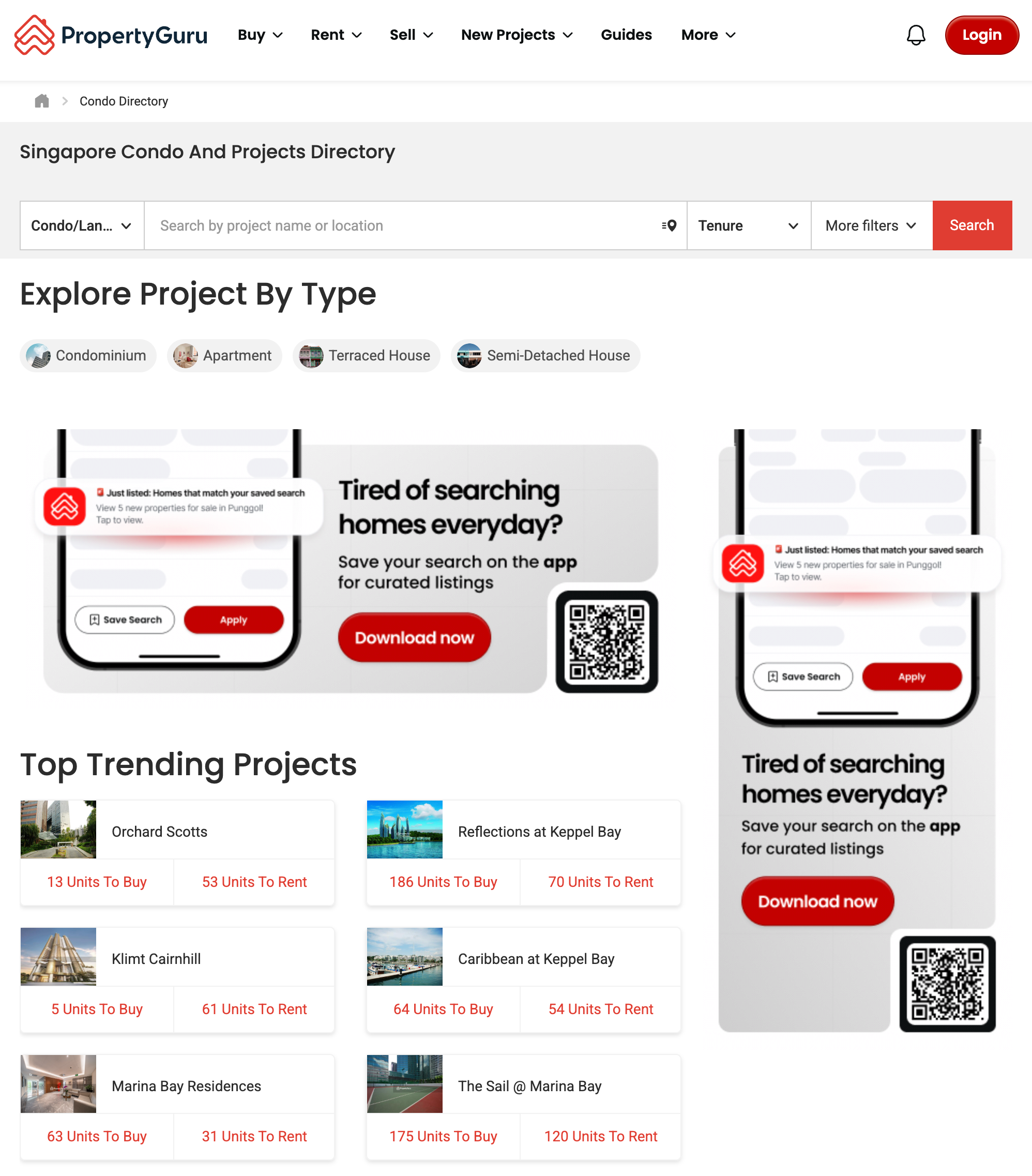

At the exact opposite end of the spectrum, you have a company like PropertyGuru (PGRU US — delisted), which was taken out by Swedish private equity firm EQT in December 2024 in a US$1.1 billion transaction.

I wrote about the company here:

What’s unique about PropertyGuru is that its property listings platforms dominate its key markets of Singapore and Malaysia. Consumers default to the largest platform, so real estate agents are forced to pay up. The platform is in a stable equilibrium that competitors will find difficult to disrupt. In other words, it has a strong economic moat.

So, how do you know if a company is selling a commodity product or not?

- You can check the company’s market share: if it’s greater than 50%, then it probably has some type of competitive advantage.

- You can ask customers why they buy the product: is price the determining factor, or are they focusing more on other attributes when buying?

- Finally, is there a market price for the product that fluctuates with supply & demand? If so, then you’re most likely looking at a commodity.

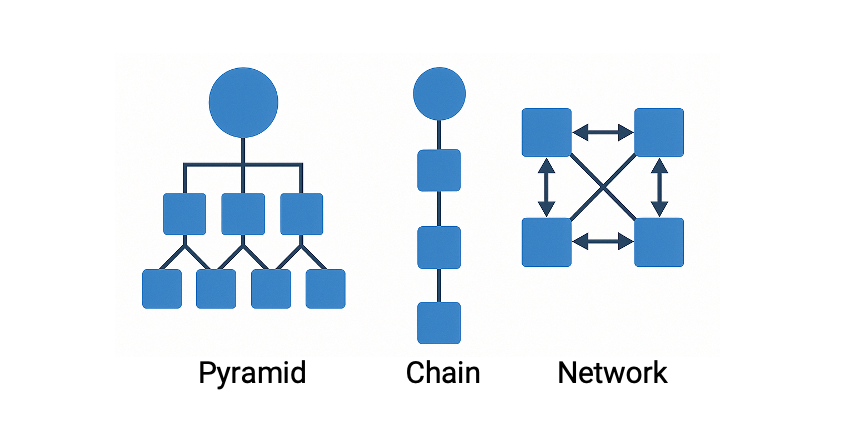

4. Avoid complex corporate structures

Earlier this year, I wrote a guide to corporate governance:

One of my key points was that complex corporate structures introduce conflicts of interest. If there are separate listed entities within a group, how can management possibly do what’s right for all minorities simultaneously?

In such corporate structures, what often ends up happening is that the parent gets involved in the business through related-party transactions. It might acquire intellectual property and require the ListCo to pay royalties to it. Or it might get involved in the distribution or the manufacturing of the products sold by the ListCo.

In such situations, hard decisions will ultimately need to be made. Will such decisions be beneficial to minority shareholders? Sometimes, but sometimes not.

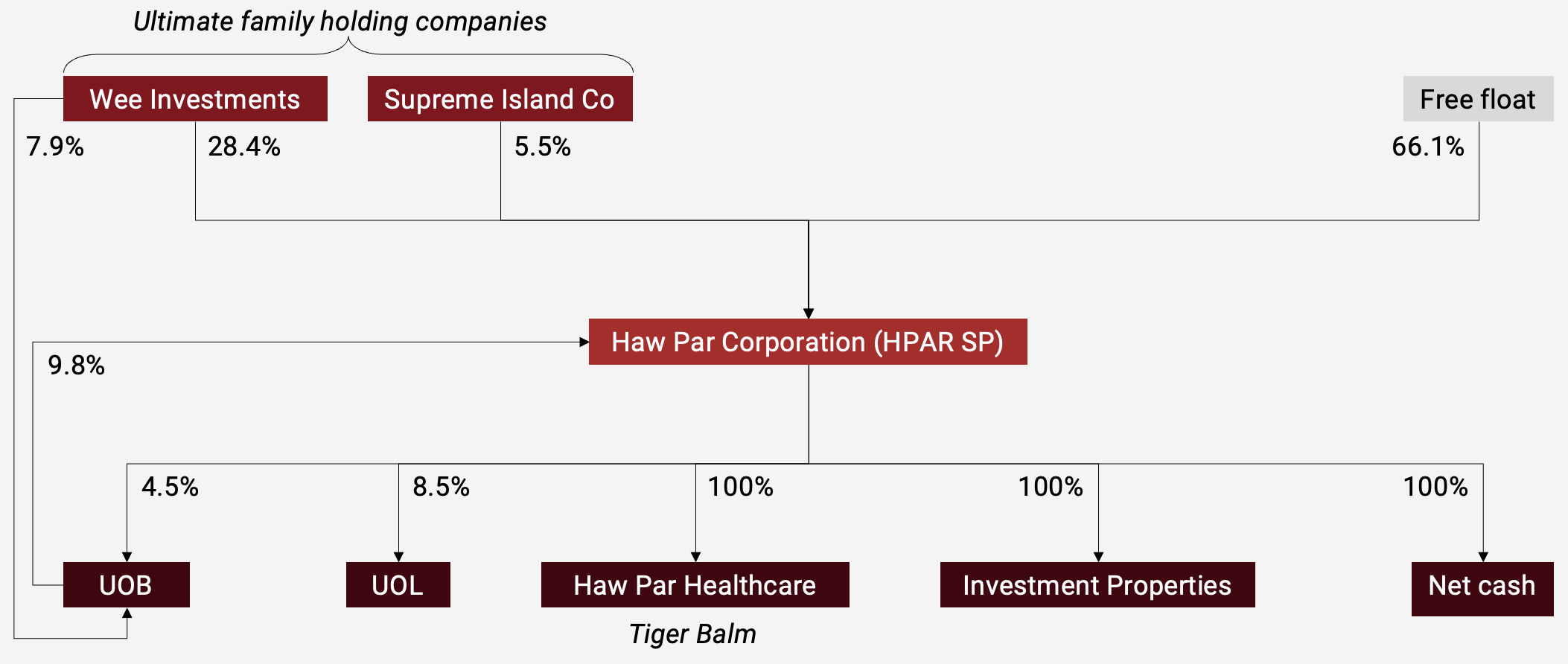

One example of a complex corporate structure is that of Singapore’s Haw Par Corporation (HPAR SP — US$2.5 billion). It’s a family-owned conglomerate with significant shareholdings in both UOB and UOL:

I wrote about the company here:

I argued that there’s significant value in its portfolio of assets, in particular the Tiger Balm franchise, the 4.5% stake in commercial bank UOB and the net cash of SG$853 million.

Now that patriarch Wee Cho Yaw has passed away, the jury’s out on whether the value of these assets might actually be realized. I argued in my post that the Wee family is facing a quandary: if Haw Par Corporation sells or distributes its share in UOB, then the family might lose control of the bank. And as a proportion of the family’s wealth, UOB matters a lot more than Haw Par Corporation itself. So there are clear conflicts of interest here.

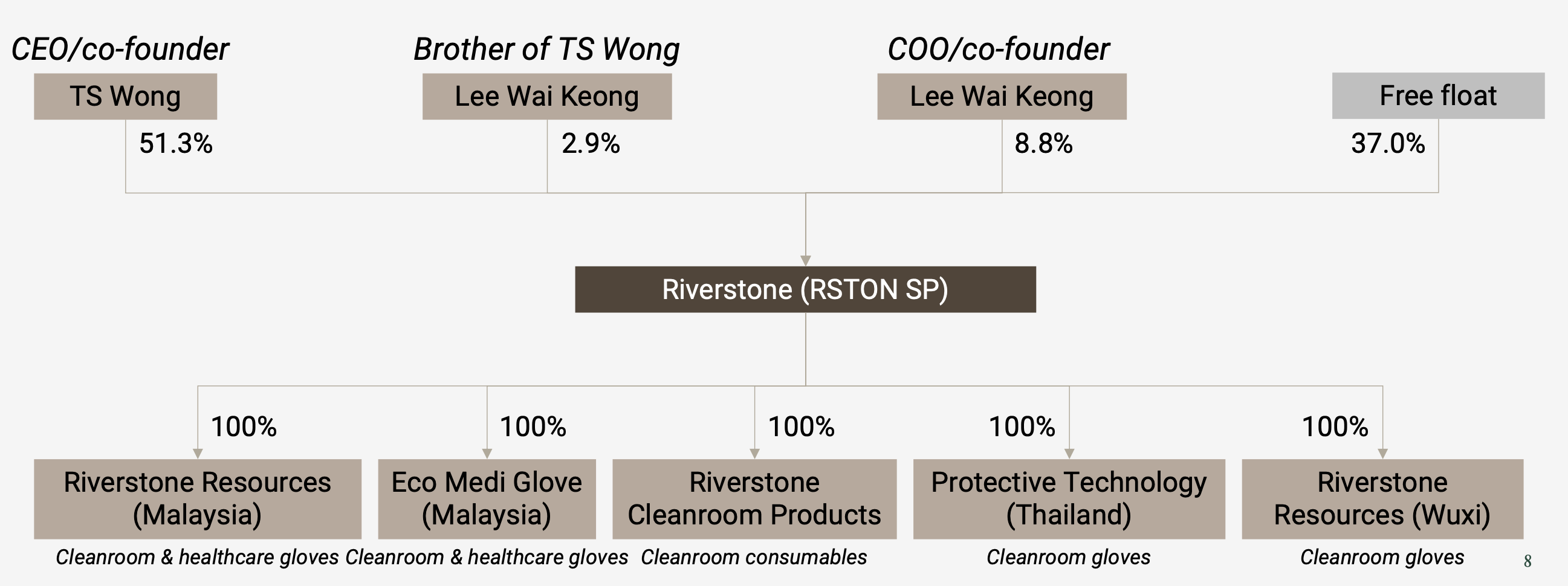

An example of a much simpler corporate structure is that of Singapore-listed Riverstone (RSTON SP — US$888 million). I wrote about the company here:

Riverstone is 51% owned by TS Wong, meaning that he has significant skin in the game:

Meanwhile, the board is mostly made up of independent directors who will hopefully take minority interests into account. I think that’s part of the reason why Riverstone’s earnings per share has compounded at a +15% annual rate since its IPO in 2006.

So, how do you check whether a company has a complex corporate structure? Search on TIKR using the company name and then click on the Ownership tab. If the parent is a holding company, ask ChatGPT what business the parent is involved in. Finally, open up the annual report and search for any related party transactions.

5. Avoid aggressive accounting

If the accounting is aggressive, that means that profits are partly illusory. Once the market realizes what the sustainable earnings power of the business truly is, the shares will probably trade down.

How do companies play these games? They might adjust their depreciation schedules, push products to customers on looser payment terms, capitalize expenses, under-estimate credit costs, etc.

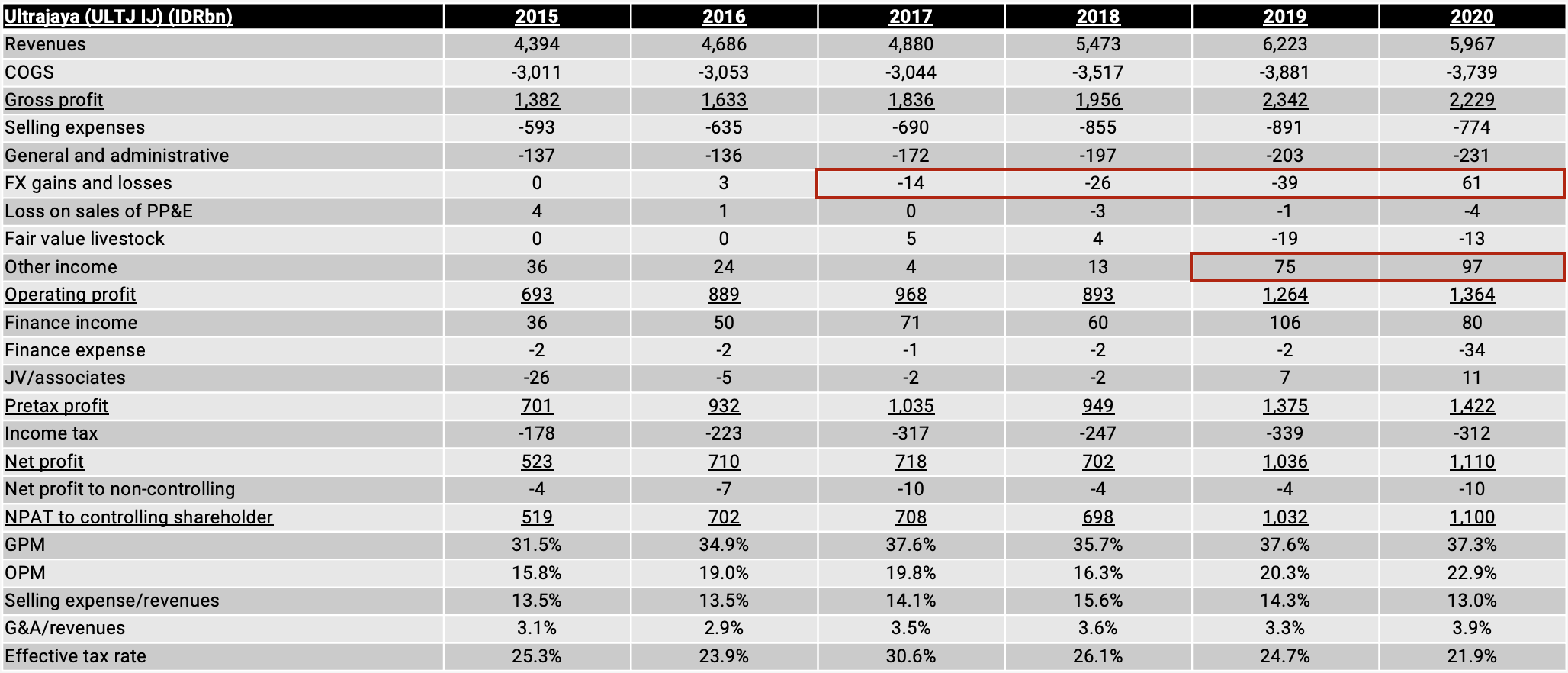

One company that I’ve previously owned is Indonesian milk producer Ultrajaya (ULTJ IJ — US$828 million):

In 2020, it had enjoyed foreign exchange gains on top of inventory revaluation gains, boosting earnings per share through 2020:

While cheap, Ultrajaya’s inventory revaluation and FX gains disappeared in 2022. And the demand for the product stays more or less flat. Since 2020, the share price has gone nowhere for almost five years. With a modest payout ratio of about 30%, the total return hasn’t been particularly high either. So it’s been a value trap.

At the opposite side of the spectrum, you have companies with accounting that’s overly conservative. China Tower (788 HK — US$828 million) is a perfect example of such a company:

China Tower owns towers where telecom operators place their antennas and other types of network equipment. These telecom operators then pay China Tower monthly rent. The profitability of tower companies can get really high if more than one operator occupies each tower.

What I felt was special about China Tower is that since 2015, its towers had been depreciated over just 6-10 years, despite useful economic lives of 10-25 years. So I was assuming that through 2025, the towers would already have been depreciated down to zero, and therefore stop weighing on earnings.

And that’s exactly what happened. China Towers earnings per share has gone from CNY 0.50 to 0.64 in the past few years and is expected to rise to CNY 1.02 on 2026e consensus estimates. China Tower would then end up trading at 10.6x P/E.

To detect aggressive accounting, you’ll need to parse through the footnotes of a company’s financial statements. Or alternatively, feed the annual reports from the last few years into NotebookLM and ask each the chatbot about each potential issue. Here is a list of items you can check:

Revenue recognition policies over time and vs peers

Receivable days vs peers and historically

Inventory days vs peers and historically

Depreciation/gross PP&E vs peers

Policies for the capitalization of R&D or software development

One-off gains or losses in the income statement

Effective tax rate much lower than the statutory rate

"Buying of R&D" through acquisitions6. Avoid cyclicals at peak margins

Cyclicals often appear the cheapest at the top of the cycle. Their margins are volatile, causing the P/E ratio to compress when margins are at their peak.

A good heuristic is therefore to avoid buying cyclicals at the peak of the cycle, even if the near-term P/E ratio looks low to you at the time.

One company whose earnings have cratered is Hong Kong-listed discount store International Housewares Retail (“IH Retail”) (1373 HK — US$78 million). I wrote about the company in the summer of 2023, when it traded at a trailing twelve-month P/E of 10x:

At the time, IH Retail had benefited from the COVID-19 pandemic, selling household goods to consumers at a time when everyone was locked up at home. IH Retail had also become a large seller of face masks. In my report, I believed that IH Retail’s profits would drop somewhat following the end of the COVID-19 pandemic.

But I didn’t expect profits to fall as much as they did: down 77% from the 2022 level.

The end of the COVID-19 pandemic was part of the issue, but IH Retail also ended up becoming a casualty of Pinduoduo’s and Taobao’s entry into the Hong Kong market. The Hong Kong discount retail market has become ultra-competitive.

A company at the bottom of its industry cycle was Singapore-based events organizer Pico Far East (752 HK — US$457 million) back in 2021.

I wrote about the company close to the bottom, arguing that the industry cycle was close to its bottom:

In 2021, Asia was suffering from the COVID-19 pandemic, and borders had closed off. As a result, conference activity ground to a halt.

However, Pico had a net cash position of HK$600 million, and it remained profitable, even through the depths of the pandemic. So I thought that the company would ultimately recover.

And indeed it did. Pico’s profits are now far higher than in 2019. When it comes to Pico’s operating margins, they bottomed out at 1.0% in 2021 and are now back to 6.9%. Investors responded by bidding up its share price.

In reality, I sometimes struggle to judge whether an industry has hit a bottom. But I like to look at a company’s operating margins over time, to see whether they’re mean-reverting or not. You can also look at the operating margins of companies in the same industry. Property developers, auto companies and chemical companies are famously cyclical. So to avoid value traps in these industries, consider whether margins may one day head lower.

7. Avoid highly indebted companies

Levered entities magnify gains and losses in both directions. On the positive side, you could argue that the debt is non-recourse to your portfolio. You’ll never risk blowing up your entire portfolio.

On the other hand, levered entities will find it difficult to invest for the long term. And if profits head south, lenders might become cautious, refuse to roll over loans and put them in a vicious spiral that eventually leads to bankruptcy.

There’s an entirely different reason for avoiding indebted companies. If a company doesn’t have any debt, it’s relatively easy to judge if it’s undervalued or not. But if a company carries a significant amount of debt, there’s always a risk that I misjudged the value and end up with a risk-reward skew that’s positive at all.

The prime example of a company with a significant amount of debt is Hongkong & Shanghai Hotels (45 HK — US$1.3 billion). When I wrote about the stock at the end of 2024, it traded at 0.28x book, roughly a third of the value of its investment properties after deducting the net debt. In that report, I argued that Hongkong & Shanghai Hotels’ earnings would probably recover as interest rates eventually came down.

However, the devil was in the details. While both Peninsula London and Peninsula Istanbul had recently opened up to the general public, they carried a significant amount of debt. And today, after paying interest expenses, they’re not contributing much to earnings at all. So with a poor return on reinvested capital and high interest expenses, the stock has gone nowhere in the past few years, despite a forceful recovery for the hospitality industry after the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s been a value trap.

A company at the opposite side of the spectrum is Japan’s BASE Inc (4477 JP — US$265 million).

I wrote about the company earlier this year:

Like many other Japanese companies, BASE has a massive cash cushion representing half of its market capitalization. While it continues to face competition from Shopify, BASE does have its fans. And given the stability of its balance sheet, it’s now attracted activist investor interest in Hiroyuki Maki. With that much cash, BASE has plenty of leeway in its attempt to stage a comeback, including in its now-successful payment segment:

How do you check whether a company has too much debt?

- Start with the EBIT/interest expense ratio. If it’s below 2x, then the company doesn’t have much room to manoeuvre, especially if its earnings are cyclical.

- For asset-heavy businesses, such as commercial property owners, you can also check the debt/assets ratio. I’d get very nervous if that number gets above 30%.

- Finally, check the yield-to-maturity on any longer-term bond that the company has outstanding. If the company has to borrow at a rate above 10%, then it’s probably in trouble. It’s going to find it hard to find projects that can justify the cost of financing.

8. Avoid government interference

Warren Buffett once said that his favorite stocks are those not targets of government regulation.

Companies can be exposed in a variety of ways: taxes or tariffs, price caps, license requirements, antitrust regulation, etc. In some regions, the rule of law might itself be lacking, in which case you’ll have no idea how you might get screwed in the future. It’s a recipe for negative surprises.

One of the first companies I covered on Asian Century Stocks was China’s Weibo (WB US — US$3.1 billion):

Weibo is a private company running a social media service that’s similar to Twitter. It completely dominates the Chinese market with 500 million users who come back to its app or website daily.

In 2020, the Chinese government cracked down on its tech platforms, including Alibaba-backed Weibo. The company was hit with 44 penalties in 2021 alone, allegedly due to the misuse of data. The government removed parts of Weibo’s key features, moving it towards safer, state-aligned content — significantly raising the moderation costs. Weibo’s ad revenue dropped, and the platform has struggled to grow ever since.

Conversely, I think that the Chinese state-owned oil & gas exploration and production company CNOOC (883 HK — US$122 billion) has actually benefited from its strong government support.

At the time of writing about CNOOC, oil prices had just turned negative, and investors were more negative than ever. But I argued that CNOOC enjoyed a monopoly on production sharing contracts in offshore China, along with great assets in offshore Guyana.

Today, CNOOC remains a growth stock, with 6% production growth annually and a reasonably generous dividend payout ratio of 40%.

While CNOOC was targeted by Trump’s Executive Order 13959 on Chinese Military Linked Companies, it has always enjoyed strong government support.

In 2022, the Chinese government invited the company to list on the A-share market, supporting the listing through direct funds. And it’s now entered into alliances in Abu Dhabi, Brazil and several other countries, also thanks to the government’s support.

So what do we learn from this? At one level, I think it’s helpful to invest in countries with a reliable rule of law, just to avoid negative surprises in the future. But if you have to invest in countries with a poor rule of law, it’s helpful to invest in entities that are aligned with the top leadership. Because if any government interference occurs, it will most likely be on the positive side.

9. Conclusion

In East Asian markets such as Japan and South Korea, value traps often end up being those that refuse to pay out cash to shareholders. In emerging markets such as Vietnam or China, the problem is more often related-party transactions and earnings being illusory in some way.

In any case, it’s always helpful to go through the list of issues that can end up causing a stock to become a value trap, including poor capital allocation, aggressive accounting, product substitutes, complex corporate structures, a high debt load, government regulation and industry cyclicality.

If you like this post, make sure to share it with your friends: