Table of Contents

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. From time to time, I may have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

1. Backdrop

Shortly after the big COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan in late 2019, the government undertook strict lockdown measures to mitigate the spread. It has had a zero-tolerance against infections, aiming to reduce the number of cases to essentially zero.

China’s zero-COVID measures were initially successful. But with the Omicron variant in late 2021, it’s become increasingly difficult for the government to eradicate the spread completely.

In 2022, Shanghai became the epicentre of a large Omicron outbreak. What soon followed was a 2-month harsh lockdown causing the economy to grind to a halt.

But Shanghai was not the only city imposing harsh lockdown measures. In fact, by April 2022, close to 200 million people in China were under some form of lockdown, affecting 22% of the country’s GDP.

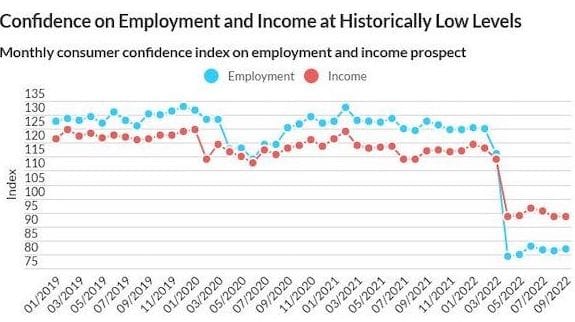

The impact on consumer confidence with regard to employment and income was dramatic:

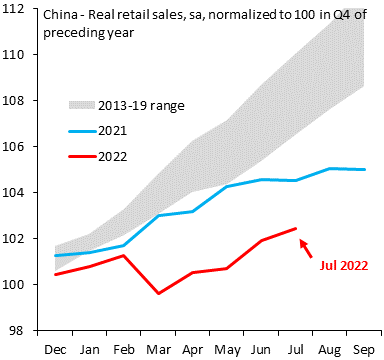

And with weaker job prospects, consumer spending took a severe hit:

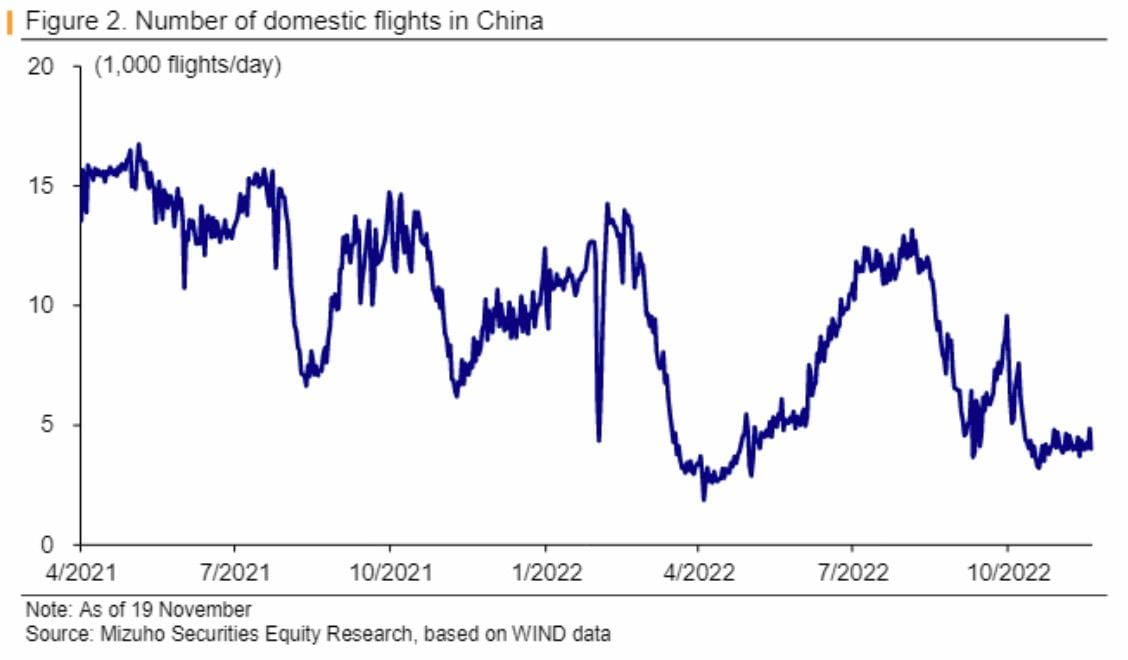

The extent to which movement restrictions were imposed can also be seen in subway traffic and flight data. For example, the number of flights per day in China decreased to around 3,000 in April and around 4,000 in October, compared to 10,000 in early 2021.

2. Consensus view

In late October, Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index reached a multi-decade low in terms of price/book. And in absolute terms - Hang Seng hit its lowest level since 2008.

But since late October, we’ve had a strong rebound. Many investors and analysts think that this rebound has gone too far. For example:

“Some investors see spreading protests against Covid-19 restrictions as an excuse to take profits after the Hang Seng gained more than 17% so far in November.” - Hao Hong, chief economist at Grow Investment Group

This rebound has really been driven by increased optimism about China’s zero-COVID policy. It looks like the government is moving away from its previous stance. Yet investors and analysts continue to be sceptical:

“Most economists doubt China will move especially swiftly, with authorities instead opting for a step-by-step approach to relaxing their Covid strategy. Mr. Lu and others say that process is unlikely to even begin until the second quarter of next year.” - Nomura

“We think that between now and April is a likely transition for the general public to adapt to the new norm. While China’s international flights have risen since May albeit off low base, domestic flights have stalled, highlighting general caution still in the current transition.” - JP Morgan

“Many public-health experts said Beijing has missed the window to put in place a gradual exit plan out of zero-Covid. For the past three years, the government has spent significant resources on building quarantine facilities and expanding mass-testing capabilities, while China’s progress on developing more-effective vaccines has been slow.” - Lingling Wei, The Wall Street Journal

“Changes to China’s COVID-19 policy do not appear to be about transitioning to the with-COVID era but rather changing the emphasis of the dynamic zero-COVID policy from zero to dynamic. Minimizing the number of cases, as with the zero-COVID policy, will remain the goal while stressing flexibility to contain outbreaks sooner, to shorten their duration, and reduce their scale.” - Mizuho

“Even if China were to end zero-covid immediately, the positive economic effects would probably not be felt until 2024… The interim period would be one of turbulence and instability. Growth would be low—and, depending on how local authorities carry out covid restrictions, protests may very well continue.” - Capital Economics

Other analysts and journalists agree that while China’s zero-COVID policy might be easing, any mass spread of COVID-19 will probably lead to chaos for an extended period of time:

“The Chinese government on November 11 released a circular on further optimizing the COVID-19 response measures. We think the impact of COVID-19 on the economy is likely to diminish in 2023, but how fast it will diminish is uncertain, so scenario analysis is required… looking forward, while we believe the worst is probably behind us, the path could still be volatile given the uncertainties in COVID-19 conditions. A more sustainable rally relies on more catalysts, especially on domestic growth.” - CICC

“Sudden reopening could lead to millions of intensive care admissions in a country with fewer than four ICU beds per 100,000 people, and where many elderly still haven’t been fully vaccinated, according to public-health experts and official data.” - Lingling Wei, The Wall Street Journal

“There is also potential for an even more disorderly 2023, in which cases run wild and authorities are forced to abandon zero-covid.” - The Economist

And finally, some argue that the zero-COVID policy simply cannot be deserted, given how central it’s become to building up the legitimacy of Xi Jinping’s rule. And that making any kind of compromise on the zero-COVID policy would be seen as a weakness.

“Such a compromise would send a signal to the general public that mass protests are an effective means to win change.”

I think that such scepticism about the end of zero-COVID is unwarranted. While stock prices have risen quite a bit since October, the bull market grow on scepticism, and it’s quite clear that the government policy is moving in the right direction.

3. Variant view

The more COVID-19 spreads in China, the closer we will be to recovery.

This is how I envisage the process playing out:

- First, the political landscape will allow China’s leaders to move to a normalisation while saving face

- State media will shift its propaganda to downplaying the threat of these newer COVID-19 variants, such as Omicron

- COVID-19 restrictions easing nationwide

- The number of COVID-19 infections will then rise rapidly before peaking sometime in early 2023

- Finally, we’ll see consumption patterns coming back to normal by around mid-2023

3.1. The political landscape shifting

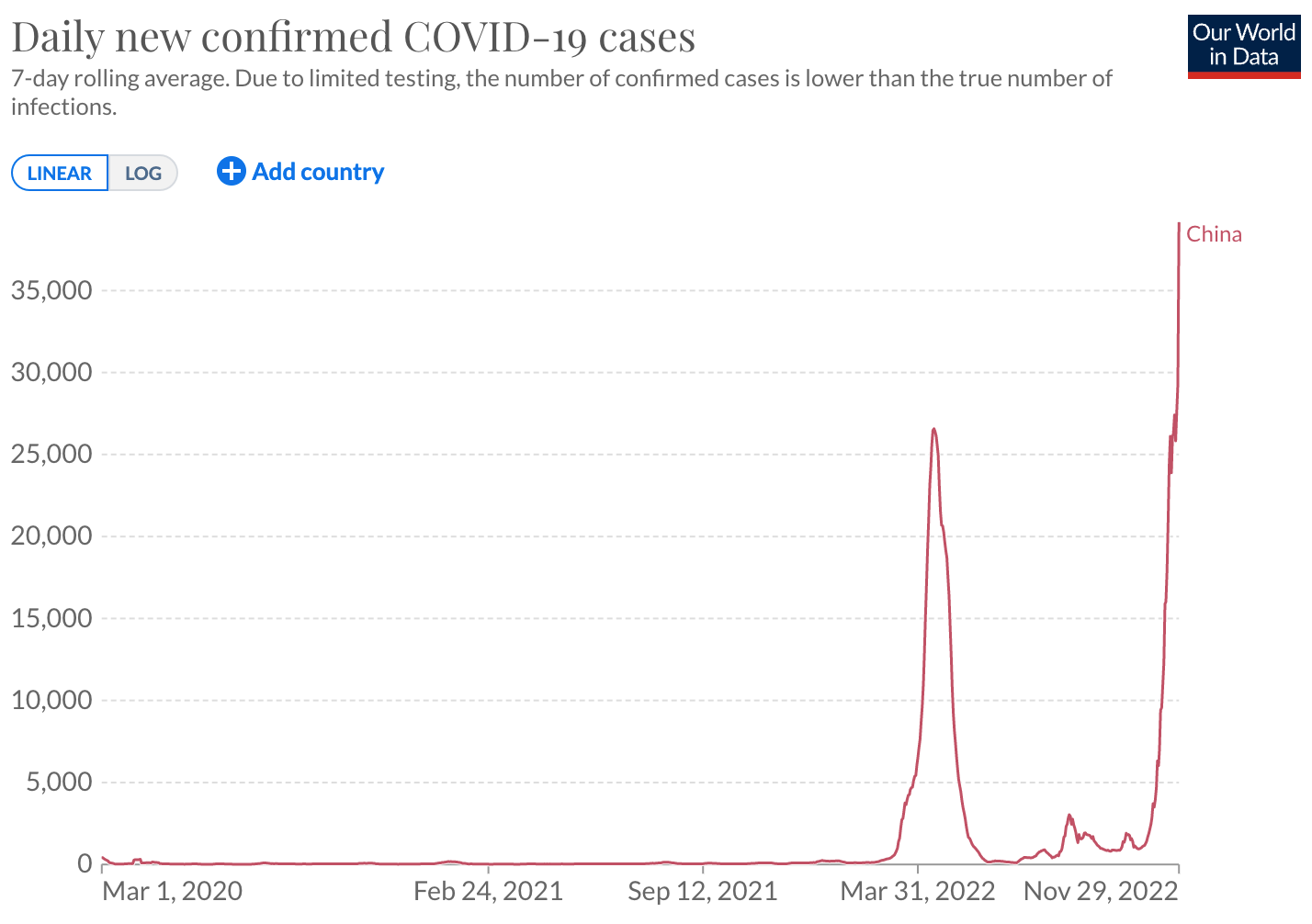

A key turning point for China’s COVID-19 policy seems to have been the Party Congress in mid-October 2022. The number of COVID-19 infections shot up right after the Party Congress. It cannot have been a coincidence.

The reason why the 20th Party Congress in October is significant is the fact that Xi Jinping secured a third term as General Secretary of the Communist Party and Chairman of the PRC (a role typically referred to as “President”).

By amending the Party Constitution to say that Communist Party members must uphold Xi Jinping’s leadership, he’s practically become a supreme leader, potentially for life. He’s finally secure in his position.

It’s also worth mentioning that he has installed loyalists in every single position on the Politburo Standing Committee, ensuring that whatever wishes he might have, they will be implemented. So Xi Jinping’s own goals and ambitions are crucial in understanding how the zero-COVID policy might be adjusted, if at all.

One of the earliest signs of a shift in China’s zero-COVID policy was Xi’s trip to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in September 2022. These were his first overseas trips in three years - a significant departure from his prior behaviour.

Then, in November 2022, Xi Jinping visited the G20 meeting in Bali. Not only did he visit Bali himself, but he also did not wear a mask - suggesting that he really doesn’t worry much about getting infected himself.

I think it’s also significant that politics have shifted domestically. An increasing number of protests have broken out, testing the government’s willingness to maintain its restrictive COVID-19 policies.

A breaking point for the protest movements seems to have been a fire in Urumqi, Xinjiang, which led to the deaths of residents in an apartment block that were locked inside due to efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19.

Social media vids from Urumqi in Xinjiang say a fire killed ten people but fire trucks were blocked from entering the compound because of Covid zero lockdown controls. #China

— Bill Birtles (@billbirtles) 5:16 AM ∙ Nov 25, 2022

Videos of the incident were not censored, at least not initially, leading to widespread opposition against such harsh measures.

Another lockdown in Foxconn’s iPhone factory in Zhengzhou caused virtual mayhem for its 200,000 employees. Food became scarce, rubbish piled up. Employees became impatient In early November, factory employees decided they had had enough, tried to flee and had clashes with local police forces.

As the world watched China erupt in protest today, YouTube once again censored our coverage. Our episode on the enormous protests at Foxconn was age-restricted, essentially killing the viewership. No reason was given. This is a travesty @TeamYouTube #China

— China Uncensored (@ChinaUncensored) 12:32 AM ∙ Nov 28, 2022

youtu.be/ZGRCtFJu-6A

By late November, similar protests had erupted across the country:

In Beijing, students came out on the streets protesting not just against the dynamic zero-COVID but also against the Communist Party and the current leadership. Such videos were censored on the mainland.

This was such a brilliant video I subtitled it so more people can watch it. Beijing students' response last night to accusations that there are 'foreign forces' at play in this weekend's protests

— Cindy Yu (@CindyXiaodanYu) 3:13 PM ∙ Nov 28, 2022

'The foreign forces you are talking about – are they Marx and Engels?'

Professor Minxin Pei wrote in Nikkei a few weeks ago that China’s restrictive zero-COVID policies are now leading to mass discontent that could even threaten the Communist Party’s hold on power:

“What zero COVID has done politically is to victimize people from all social backgrounds at the same time -- and make them relate to each other in terms of their shared frustration with a seemingly tone-deaf, arbitrary and incompetent government. In other words, the party's zero-COVID policy has inadvertently forged a common identity -- as victims of a senseless policy -- for people across various social divides…. Leaders have to make tough choices. Ending zero COVID would be by far the lesser of two evils, however unattractive it may seem to Xi and the party.

The current situation is untenable. Chinese citizens are increasingly opposed to strict zero-COVID measures. And Xi Jinping himself is probably secure enough in his own position to be able to make a compromise and let Omicron spread.

3.2. State media shifting its messaging

Over the past two years, the prevailing narrative around COVID-19 in China has been that the vaccination uptake hasn’t been good enough. And that if you let COVID-19 spread, it would pose a massive risk to the elderly population. State media has also repeatedly said that the country’s medical system would be unable to deal with the deaths resulting from any large-scale COVID-19 outbreak.

Such claims are, in my view, dubious. Roughly 90% of China’s population has been vaccinated with the homegrown Sinovac vaccine. It offers some protection against Omicron. And Omicron does not lead to particularly high case fatality rates, at least not in other countries. Hong Kong’s inability to deal with its early 2022 Omicron outbreak was self-inflicted, as it required all patients even with mild symptoms to stay in hospitals.

I think that we’re finally starting to see the narrative about COVID-19 shifting in China. For example, on 4 November, the pro-Beijing newspaper Ta Kung Pao wrote reported that Omicron infections are actually mild in general:

"Compared to the Delta variant and the original strains of COVID-19, the proportion of patients who suffer serious severe cases has been greatly reduced with Omicron. The risk of asymptomatic infections leading to long-COVID is extremely low, and the risk of mild infections leading to long-COVID is far lower than those of those had severe infections." (Translation of “相较于德尔塔变异株和原始毒株,奥密克戎大流行阶段的新冠后遗症比例已大大降低。无症状感染者出现新冠后遗症的机会微乎其微,轻症者出现新冠后遗症的比例也远远低于重症者”)

And since then, we’ve seen several other state media publications suggest the same thing.

For example, on 29 November, Global Times commentator Hu Xijin downplayed the severity of Omicron, saying that the proportion of severe cases is only 0.025% (data source unknown). And that most Chinese people are no longer afraid of being infected:

The new Omicron variant is spreading fast,pushing adjustment in COVID response in many parts of China.China's current rate of severe cases is about 0. 025%.Most Chinese people are no longer afraid of being infected.China may walk out of the shadow of COVID-19 sooner than expected

— Hu Xijin 胡锡进 (@HuXijin_GT) 4:58 PM ∙ Nov 28, 2022

Also, on 29 November, the local state newspaper “The Beijing News” published a 5,500-word interview with people who had been infected with COVID and recovered. The main message was that infections were generally mild:

Important signal from official media. The Beijing News, a paper affiliated to the municipality, today published a 5,500-word interview with various people who had Covid and recovered to speak their experiences. Main message: everything is fine. Trending in China's Weibo!

— Chen Long (@chen_long) 5:51 AM ∙ Nov 29, 2022

Then, on 1 December, Vice Premier Sun Chunlan commented that Omicron’s pathogenicity is weakening, suggesting that the virus is no big deal anymore:

“With the weakening of the pathogenicity of Omicron virus, the popularization of vaccination and the accumulation of prevention and control experience, China is facing a new situation and new tasks in epidemic prevention and control.”

State media outlet Global Times quoted an expert from Wuhan University who suggested that COVID-19 is no longer as dangerous as it used to be:

"COVID-19 is no longer as dangerous to humans as it used to be, so we do not need to panic about Omicron variants."

In mid-November, the state-run newspaper People’s Daily started reporting on serious COVID-19 cases - or rather the lack of serious cases - in China’s key cities. In those stories, it suggested that the lack of serious cases is thanks to the government’s early detection and control. You get the impression that People’s Daily is now trying to downplay the threat of Omicron - that if you get infected, you have nothing to worry about.

Several articles about COVID-19 in the past month have also failed to mention the concept of “dynamic zero-COVID”. Instead, they’re now using words such as “active control”. In the past, state media would typically argue that China should “unswervingly stick to its zero-COVID policy”. I believe that we’re witnessing a change from the past.

Finally, the government has started to listen to citizen complaints about the zero-COVID policy and signalled its intent to adjust it:

“The most important development from the past few days is that there is a public debate on the zero-Covid policy in China… The government did not react by shutting those voices down. Instead there are signals that the government is listening to the public and taking actions to address their concerns.” - Zhiwei Zhang, PinPoint Asset Management

3.3. COVID-19 restrictions easing nationwide

The population has increasingly become fed up with excessive COVID-19 restrictions. And people increasingly realising that Omicron, in most cases, does not lead to serious disease. With this backdrop, the government is probably feeling empowered to deal with COVID-19 in a more scientific fashion.

Officially though, there has been no shift away from the zero-COVID policy. But small steps have led to an incremental - de facto - loosening of restrictions.

On 11 November, for example, the government released a circular announcing 20 new prevention and control measures. These new measures confirm the general policy of “dynamic zero-COVID” but emphasise “optimising” and “adjusting” the COVID-19 response.

Specifically, the central government wants local authorities to consider virus mutations to make the response “more targeted and science-based”. The new policy also emphasised “minimising the impact of the epidemic on economic and social development”. I interpret this to mean that COVID-19 can spread as long as people’s health and livelihoods are protected.

We’ve seen a number of new measures being introduced. For example, cutting the quarantine period for inbound travellers, a lack of contact tracing for secondary infections and a seven-day home quarantine for those who have visited high-risk areas instead of dedicated quarantine facilities.

There are now rumours that supplementary COVID-19 policies will allow even positive cases to quarantine at home. That would mark a shift towards living with endemic COVID-19, similar to the policies that many other Asian countries have adopted since Omicron came into the picture in late 2021.

#China to release supplementary COVID-19 measures in the coming days, which will allow positive cases and close contacts to quarantine at home with conditions.

— CN Wire (@Sino_Market) 7:01 AM ∙ Dec 1, 2022

China to step up antigen testing for covid-19, reduce the frequency of mass testing and regular PCR tests. -Reuters

Cities are now being classified as either high-risk or low-risk zones. Cities with a low amount of infections will then enjoy lax restrictions. For example, Guangzhou just opened after becoming classified as “low risk”:

广州解封:解除所有疫情防控临时管控区,按低风险区管理。广州躺平了。

— Hao HONG 洪灝, CFA (@HAOHONG_CFA) 7:30 AM ∙ Nov 30, 2022

Guangzhou reopens, re-classified as “low-risk” zone.

And the central government is now criticising local governments of excessively their excessively strict implementation of China’s zero-COVID policy. It seems to be shifting the blame:

“The NHC named seven cities where their pandemic prevention and control policies need be corrected during a Saturday press conference held by the Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council. Some of the problems cited were local governments applying excessive quarantine and lockdown measures and extending movement restrictions to unaffected areas.”

No longer are local governments judged favourably if they implement strict lockdowns as Shanghai did in March 2022. Today, local government officials will be penalised if they take things too far. In practice, this means a sequential loosening of the COVID-19 control policy.

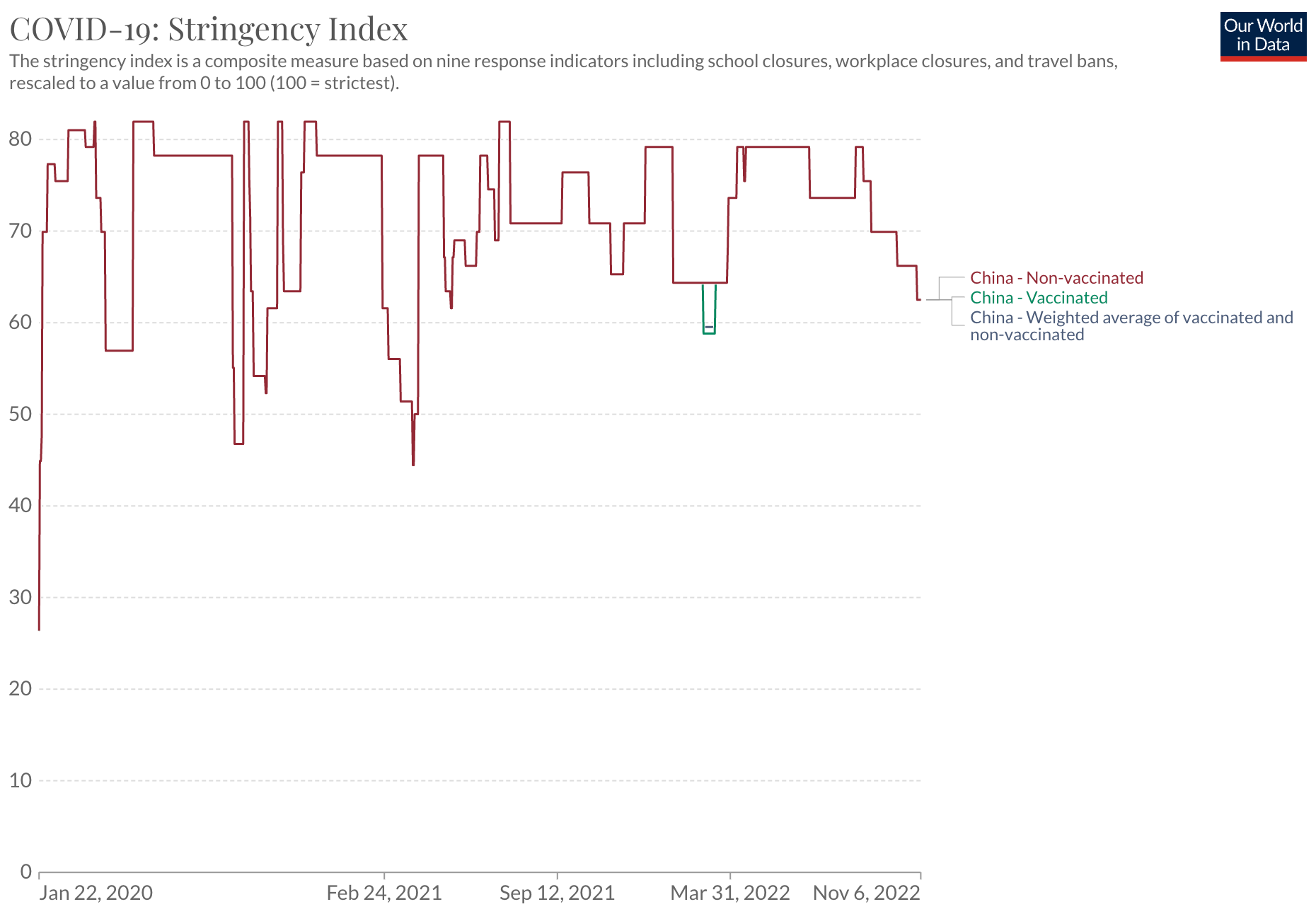

So the result of all of these above reforms is that China’s COVID-19 stringency index - which measures the severity of movement restrictions - has dropped steadily since October:

Chris Wood at Jefferies speculates that further easing in China’s zero-COVID policy could take place if the World Health Organisation’s shifts its view of the pandemic at their next meeting in January 2023. He believes that such a shift could give China a face-saving out for a policy change. For the record, WHO still considers COVID-19 a “public health emergency of international concern”.

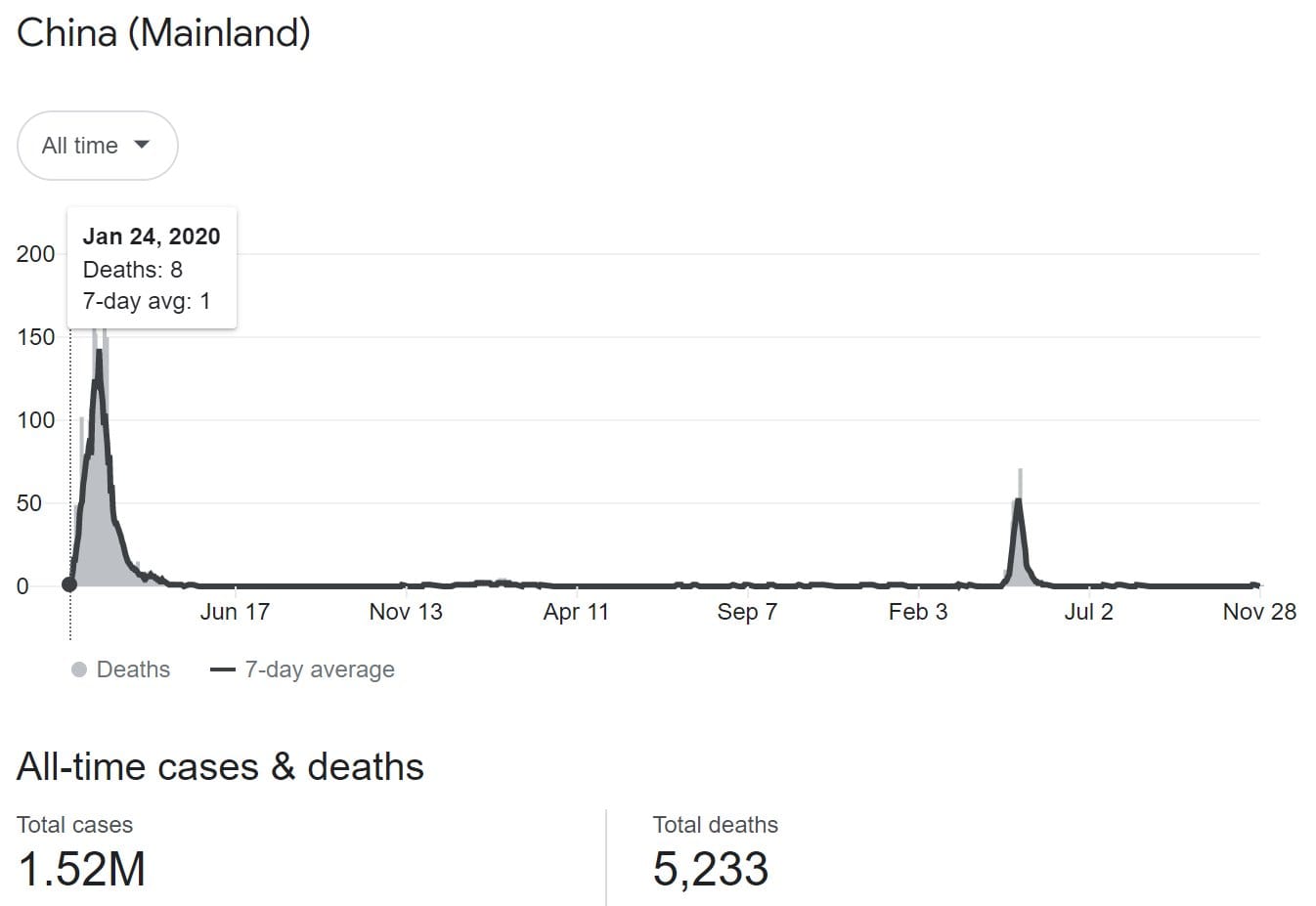

COVID-19 is now spreading across China. But what’s remarkable is that the death rates remain low, at least on the government’s reported numbers. Some analysts believe that deaths are underreported. But even if that’s the case, it still signals the government’s intent to downplay the threat of Omicron.

Given the large-scale construction of makeshift hospital beds, it looks like the government is preparing for mass outbreaks. It wants to be prepared if and when Omicron starts spreading.

One of the largest quarantine camp in China's Guangzhou city is being built, per AP.

— unusual_whales (@unusual_whales) 12:51 PM ∙ Nov 29, 2022

It has 246,407 beds, including 132,015 in hospital isolation wards and 114,392 for people who are infected but have no symptoms of Covid.

I believe we’re now witnessing the early stages of a controlled spread of COVID-19, which will last for a few quarters. China’s zero-COVID policy has essentially shifted from containment to mitigation.

4. Implications for investors

The sectors that have suffered the most from China’s zero-COVID policy are consumer related. Consumer spending has been weak, especially regarding offline retail, restaurants and so on. These businesses are likely to recover at some point.

The transportation sector has also been weak. Toll road volumes, airport passenger numbers and railway ridership are still much lower than they were before the pandemic. I expect mean reversion as restrictions lift in the next few months or quarters.

I believe that oil demand will also shift upwards as air travel resumes and cars get back on the road. This will have implications for oil & gas producers as well retailers of gasoline.

Next week, I’ll write about one of the companies that should benefit from China’s re-opening. To make sure you don’t miss it, subscribe by clicking the “Subscribe now” button below: