Table of Contents

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

- In the past year, cocoa prices have spiked to elevated levels. The culprit has been heavy rainfall in West Africa, leading to poor cocoa crops.

- There’s nothing suggesting that the tightness in the cocoa market will end anytime soon. Sea temperatures and the cocoa stock-to-grindings ratio remain at extreme levels. But if history is any guide, the cocoa market will return to balance within three years.

- High cocoa prices are a big headwind for processors like Barry Callebaut and chocolate manufacturers like Delfi. But they’ll eventually be able to pass on the higher costs to consumers, which typically takes about two years.

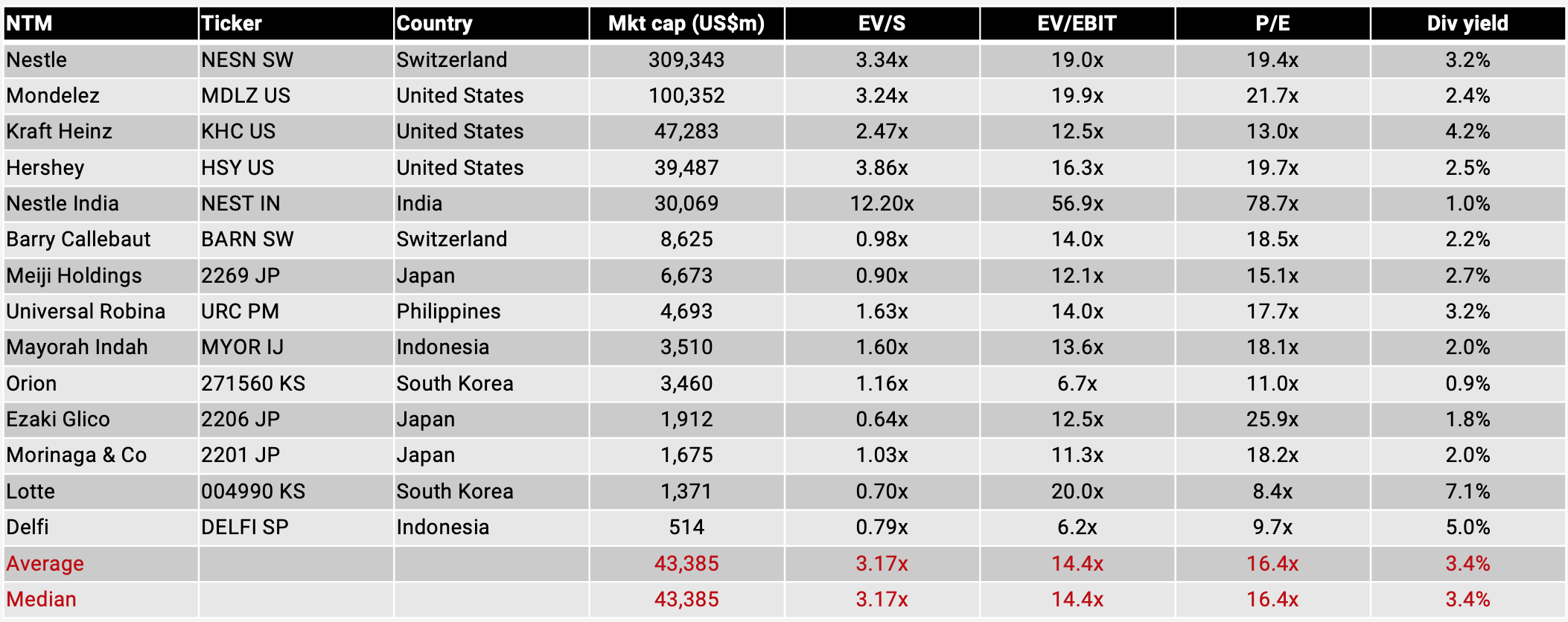

- The valuation multiples for Asian chocolate manufacturers such as Delfi and Orion remain lower than the global average, even though they have less exposure to geographies where the weight-loss drug Ozempic is popular. This strikes me as an anomaly. It probably reflects global investor preference for “quality stocks” in either the US or continental Europe rather than here in Asia. But that could change.

Cocoa prices have increased in the past year, leading to higher costs for chocolate producers like Delfi and Hershey. Prices are now roughly twice as high as they were in 2017.

The culprit for this increase in cocoa prices is extreme rain in West Africa, which has caused poor crops and a supply deficit.

The question is how long the current tightness in the cocoa market will last and when we should expect future prices to return to earth. This will impact chocolate producer margins, including those of Delfi. The current increase in cocoa prices is a repeat of the 2008-2011 period, leading to a temporary drop in margins for chocolate makers.

Introduction to cocoa

Cocoa is a key ingredient in chocolate - a US$47 billion industry. We consume 3 million tons of cocoa beans yearly, most of which is via chocolate. The attraction of chocolate is its mood-enhancing effects through phenylethylamine, anandamide and caffeine, which can provide a feeling of euphoria.

Consumption has occurred for several millennia, first in the Amazon rainforest of Ecuador and later on in present-day Mexico. Back then, it was mostly consumed as a beverage. For example, Spanish records suggest that Aztec emperor Moctezuma II consumed 60 portions of cocoa beverages each day.

Christopher Columbus encountered cocoa on his fourth voyage to the Americas and then spread the beans to Europe. After using it as medicine, entrepreneurs realized they could take away some of the bitterness by adding sugar to it. And voila, chocolate was born.

The raw ingredient of cacao comes from the cacao tree, theobroma cacao. These carry cacao pods, which ripen twice a year and contain 30-40 cacao beans each nestled in sweet, white pulp.

To extract the cacao, farmers scoop out the beans and place them in boxes covered with leaves to spark fermentation. After fermentation, the beans are dried in the sun for about a week before they’re cracked open to reveal the cacao nibs inside. These nibs are eventually ground into a thick paste called chocolate liquor. The raw ingredient is known as “cacao” and the end product is known as “cocoa”.

There are three main types of cacao trees: Forastero, Trinitario and Criollo. 80-90% of modern chocolate comes from beans from the Forastero trees, which tend to be hardy and disease-resistant. Criollo, on the other hand, is a prized variety that’s less bitter and more aromatic. It tends to be expensive. Trinitario is a genetic mix of the two.

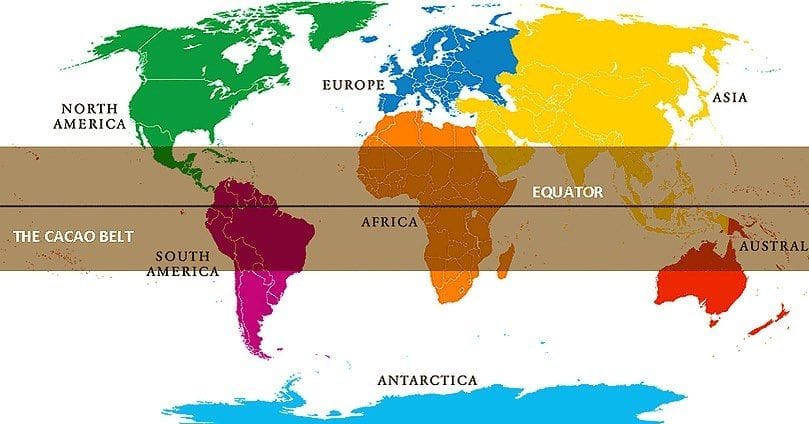

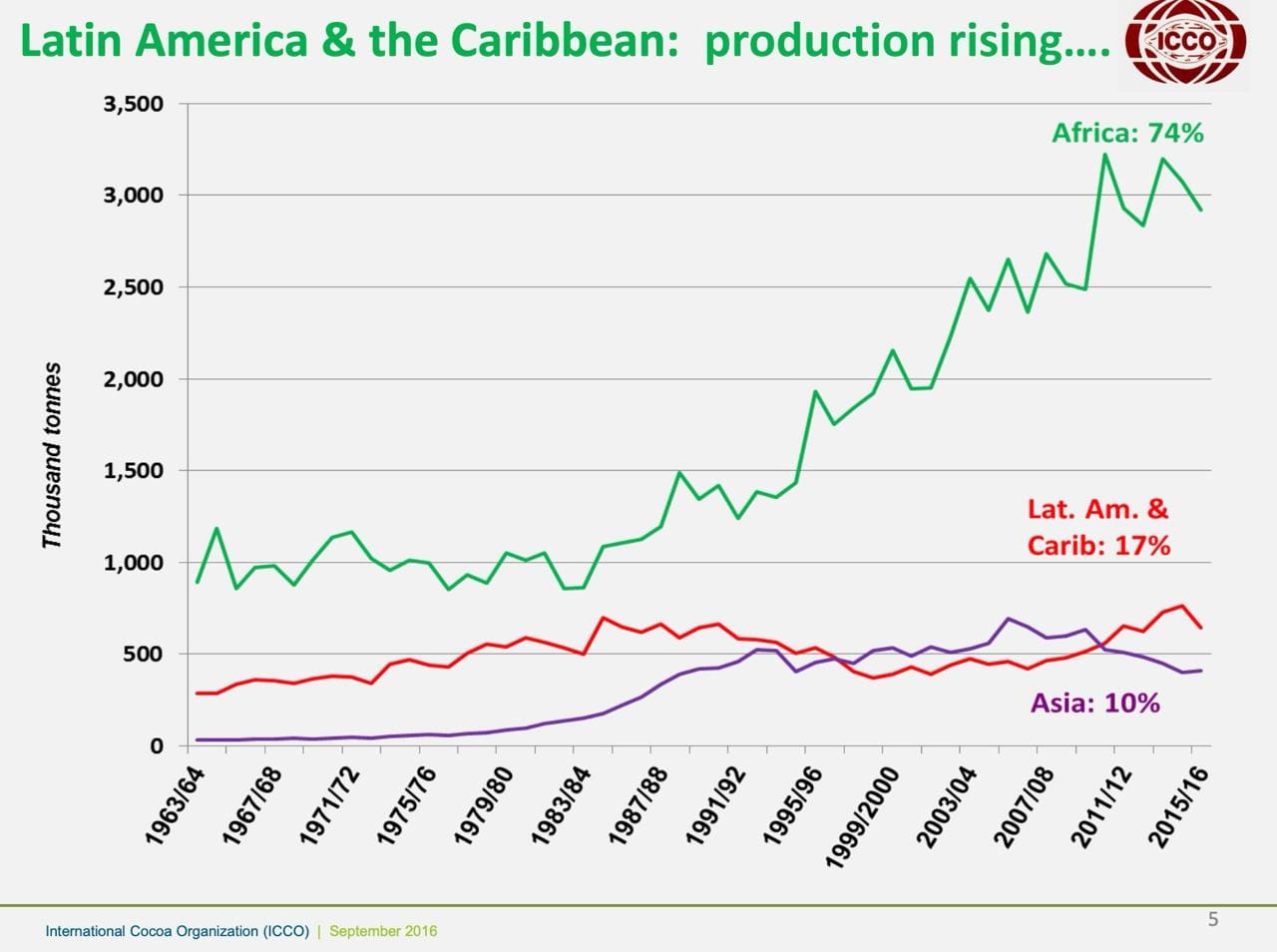

These cacao trees thrive in hot, humid climates near the equator. The fact that cacao trees need a specific climate 10-20 degrees from the equator has led a few countries to completely dominate the supply, primarily Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana. Roughly 70% of all cocoa is produced in these two countries. Ghana cocoa tends to be fruitier with floral notes, and Ivorian cocoa is nuttier with an earthier flavor.

Outside of West Africa, there’s also some cocoa cultivation in South America, and Indonesia has also emerged as a major grower. These countries tend to focus on premium varieties.

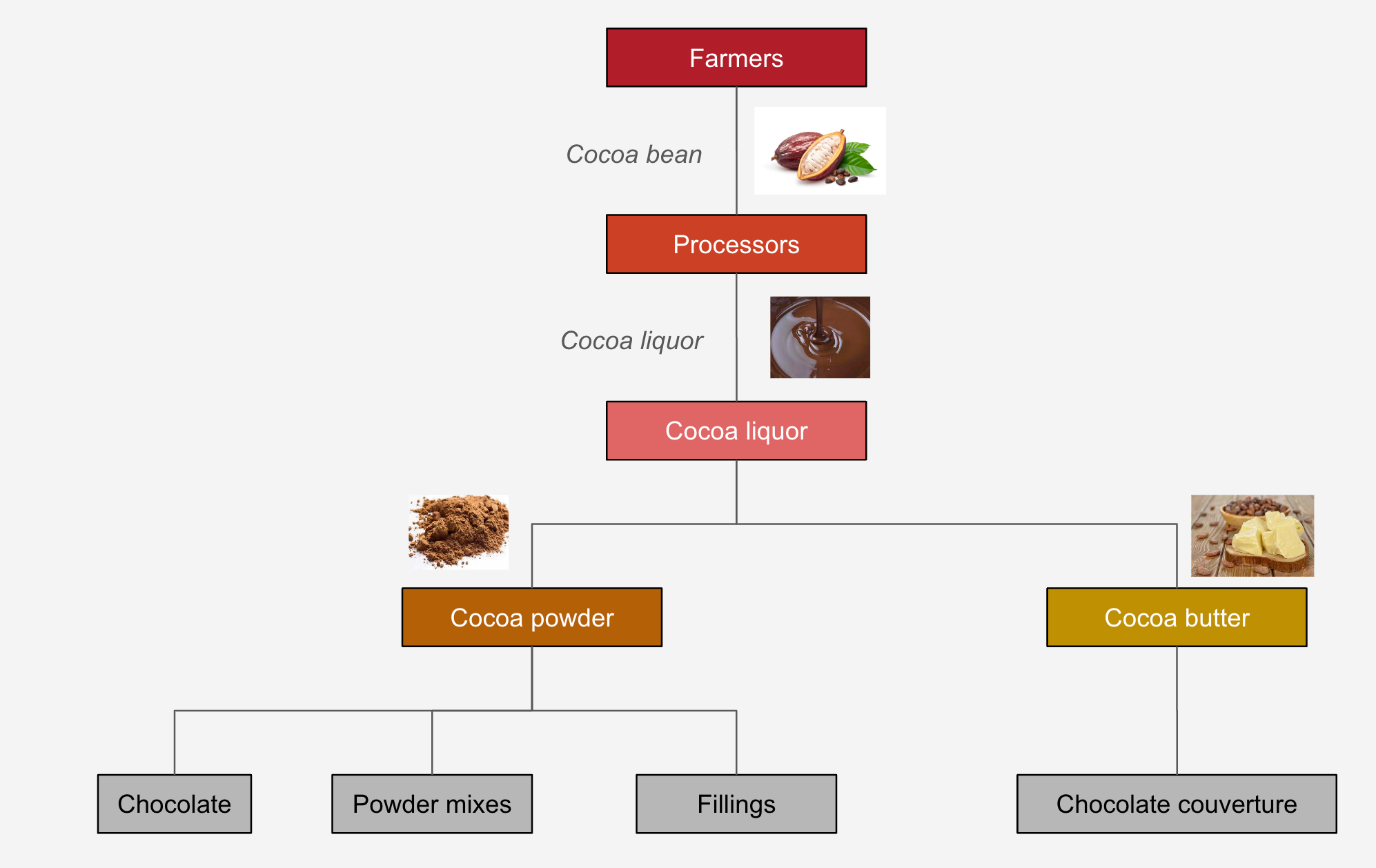

The cocoa supply chain is simple:

- Farmers harvest cocoa beans from pods on cacao plants, then ferment and dry them before selling them to intermediaries.

- Traders such as Cargill, Barry Callebaut and Olam export the packaged cacao beans to processing factories close to customers in Europe, North America, etc. The top 5 exporters totally dominate the trade, including, for example, 80% of Côte d'Ivoire supply.

- The processing companies winnow, roast and grind cocoa and convert it into cocoa liquor, cocoa butter or cocoa cakes, which are then mixed with sugar and milk to produce chocolate. The largest processing country is the Netherlands at 13%, but Europe controls roughly 40% of the market. Here is what the process looks like from farm to table:

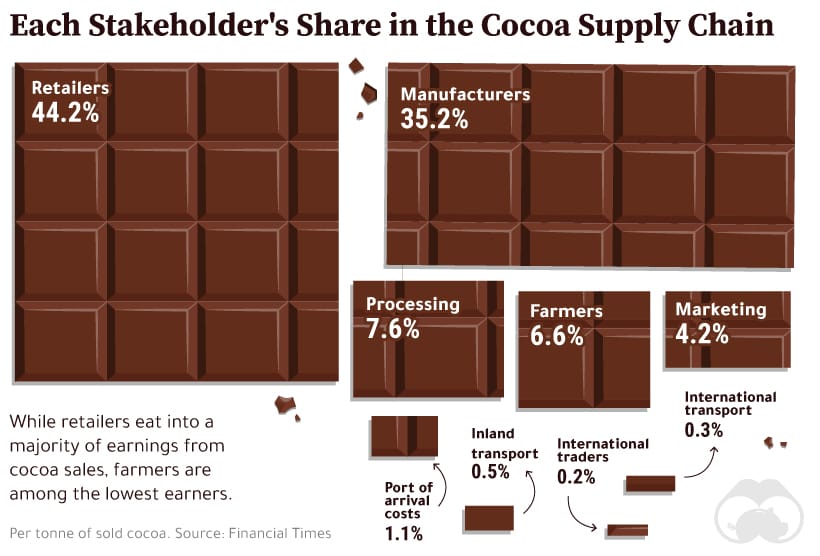

Chocolate production is profitable, but the vast majority of industry economics end up in the hands of either retailers or manufacturers. Farmers, on the other hand, only get around 5-6% of the total value, a number that’s dropped from about 8% previously.

Demand grows at a steady pace

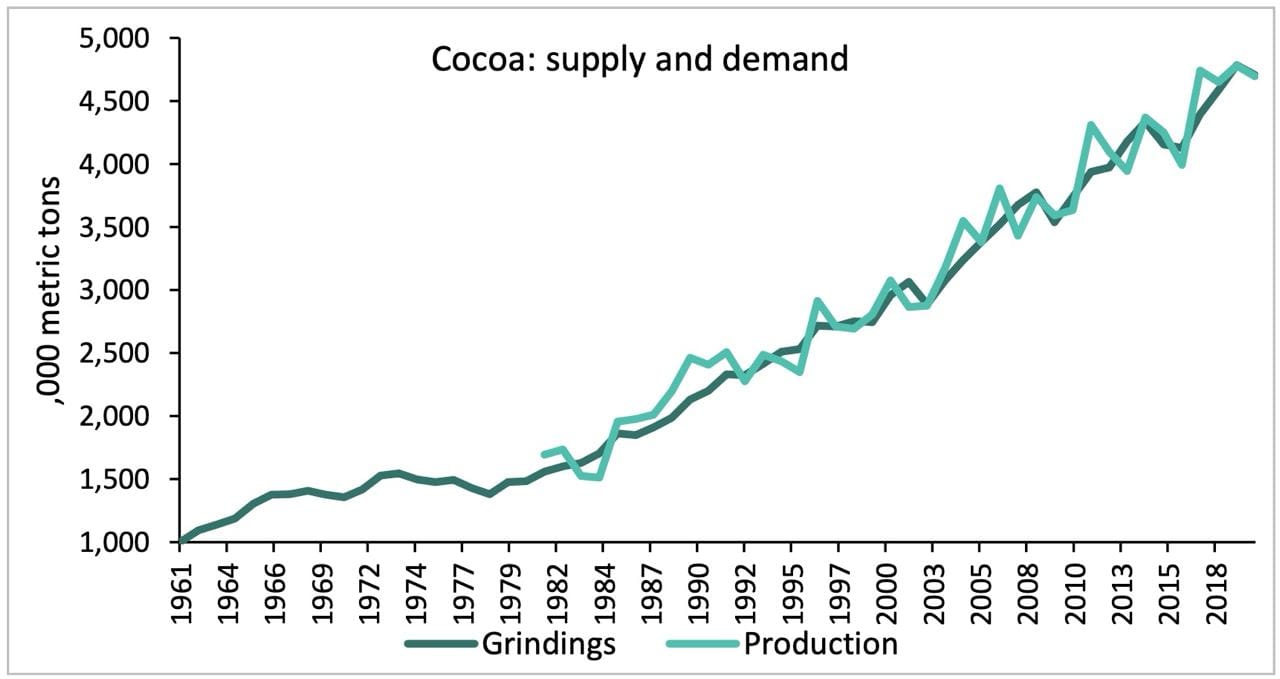

Over the past sixty years, cocoa consumption has grown at an average rate of about 2.5% per year. There’s been remarkably little variation, growing across almost all consecutive three-year periods. The chart below shows grindings (demand) measured in thousands of tons vs. a much more volatile production (supply).

What’s driving this 2.5% yearly volume growth is greater consumption in large emerging markets such as India and China, but also smaller markets that are adopting Western eating habits, including Indonesia and Vietnam.

In addition, developed market consumers are moving towards healthier and more premium chocolate products such as Lindt, which tend to contain less sugar and a higher level of cocoa. That also increases the demand for cocoa, all else equal.

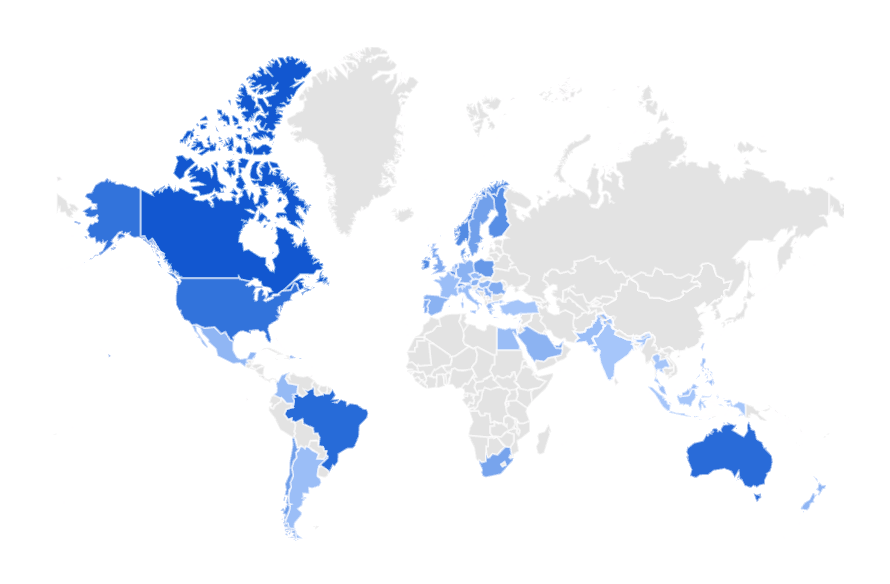

On the negative side, the emergence of the weight-loss drug Ozempic has raised the question of whether we might see a permanent drop in the demand for cocoa. There are signs that the demand for cocoa is weakening in markets where Ozempic is popular, including the United States.

The key determinants of cocoa supply

The broad picture is that cocoa bean production tends to meet demand in most years with only a few dislocations historically.

However, in recent years there seems to be an underinvestment in West African cocoa trees that might damage production for years to come. It takes about five years for a cacao tree to mature and produce pods. There’s also the issue that there are no more forests in Côte d'Ivoire to clear.

Part of the problem might be a lack of incentives for farmers to scale up production. Nearly 60% of world cocoa processing takes place through processors and trading houses Barry Callebaut, Olam and Cargill, which have a certain degree of bargaining power against West African traders.

In the past, Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana have tried to corner the market to drive up prices. In 2018, they signed the so-called Abidjan Declaration, which was meant to become the cocoa version of OPEC - or “COPEC” as it was known. But buyers complained, and they eventually had to back down on this initiative and charge market prices instead.

There’s been some hope that new techniques could help improve yields. Research in Côte d'Ivoire and elsewhere has tried to improve farming techniques. However, data on cocoa farming suggests no noticeable improvement in production yields.

In the short term, what matters most for prices is the weather. For example, in the past year, West Africa has suffered from high rainfall and severe winds, making it difficult to dry cocoa beans and have caused harvests to disappoint.

The weather factor

To understand cocoa prices, we’ll need to understand how the weather in West Africa impacts seasonal crops.

One of the greatest cocoa traders ever is Englishman Andrew Ward, known as “Chocfinger”, referring to the fact that he controlled the chocolate market in the same way that Goldfinger controlled the gold market.

Chocfinger has been famously obsessed with the weather factor in predicting cocoa prices. When he was actively trading cocoa, he would set up his own weather stations on the west coast of Africa to monitor cocoa crop growth at any given time. He would also send employees to count the average number of cocoa pods per tree to get proprietary data ahead of the market.

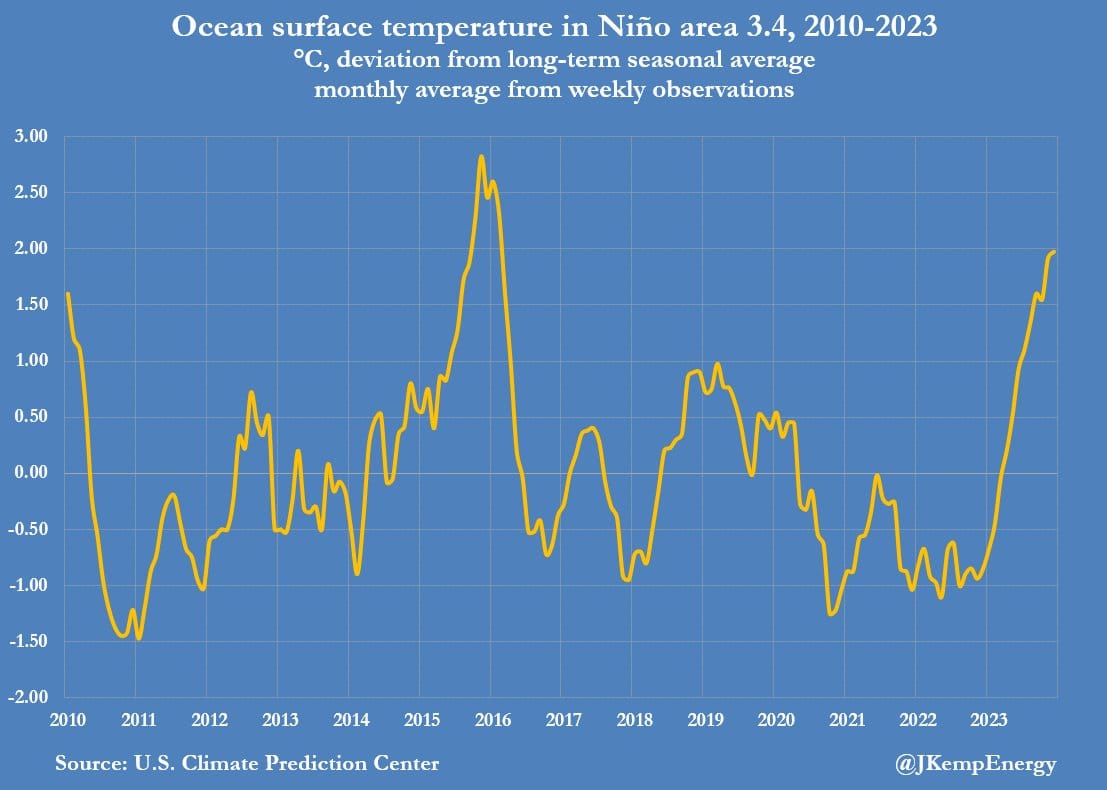

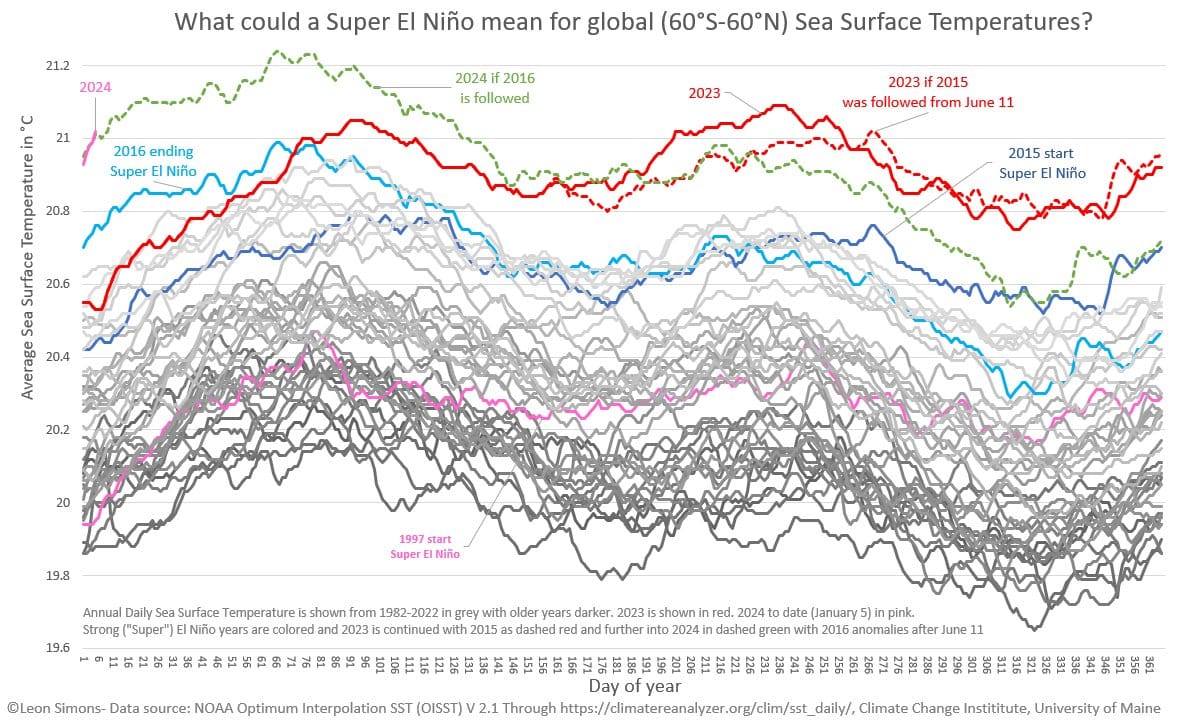

In any case, the weather in 2023 has been extreme. The so-called El Niño-Southern Oscillation has occurred for centuries, with regular warming and cooling of sea surface temperatures occurring every other year or so. The warm phase of the oscillation is called “El Niño” and the cold phase “La Niña”.

But in 2023, we not only had an El Niño pattern, but temperatures rose significantly beyond what was predicted by most weather models:

Sea surface temperatures reached record highs, causing trade winds to weaken, the Atlantic jet stream to shift southward and heavy rains to occur through most of West Africa. Such rainfall has not only made it more difficult to dry cocoa beans but has also promoted black pod disease, causing beans to turn black and rot.

In early 2023, an El Niño pattern was identified, and scientists expected slightly higher surface temperatures. But the actual temperatures measured ended far higher than expected, which is what caused the heavy rainfall in West Africa by the end of the year.

Nobody knows what caused this massive upward shift in temperatures: perhaps lower sulphur emissions after the introduction of IMO 2020, perhaps a belated effect from factory shutdowns and restarts after COVID-19, perhaps sun spots or perhaps certain volcanic eruptions.

In any case, the latest production data suggests that we’ll end up with the second consecutive year of a supply deficit in the cocoa market. The deficit is improving somewhat, though, with production for the past year up +2.6% while the demand is up about +0.2%. But the market is still tight.

Data from the International Cocoa Organization (“ICCO”) shows that crops arriving at ports in Côte d'Ivoire since the start of the season on 1 October 2023 are down 35% compared to the same period last year. And in Ghana, crops from September to November were down 51%. ICCO’s commentary is bleak:

“The rise in prices for the ongoing season has been underpinned by supply tightness. It currently seems there is no sign of respite from price increases.”

The best measure of whether the cocoa market is in over- or undersupply is the stocks-to-grindings ratio. This measures the inventory (stocks) of cocoa beans compared to the estimated grindings in tons for the current year. ICCO estimates that the stock-to-grinding ratio, on average, explains 83% of annual changes in cocoa prices in the long term. I view the stock-to-grinding ratio as a coincident indicator.

Typically, a stocks-to-grindings ratio above 40% suggests that there are enough stocks to meet processing needs even if future harvests should turn out lower than expected. Any ratio below 35% would suggest a tight market. And today, the stocks-to-grindings ratio is 34.9%, suggesting extreme tightness in the cocoa market.

On the demand side, however, we’re starting to see weakness:

- US chocolate sales in the four weeks ended October 8 fell -9.2% year-on-year (source: Circana)

- North American Q3 cocoa grindings fell -18% year-on-year (source: The National Confectioners Association)

- Asia Q3 cocoa grindings fell -8.5% year-on-year (source: The Cocoa Association of Asia)

- European Q3 cocoa processing fell -0.9% year-on-year (source: The European Cocoa Association)

So, as you can tell, the weakness is particularly pronounced in North America, and I think that’s probably due to the impact of the weight-loss drug Ozempic. The Asian weakness probably has more to do with economic weakness and a customer pushback to higher prices.

The impact of record cocoa prices

Cocoa beans, cocoa butter and cocoa powder have active futures markets, with London focusing on West African cocoa and New York on Southeast Asian cocoa. London prices are now just a hair off their previous peak of £3,500/ton, but still almost twice the level seen in 2017.

What typically happens when you see such price spikes is that farmers respond by planting more trees. ICCO estimates that a 10% increase in farmer prices on average leads to +0.6% higher supply in the same year year. Given global cocoa production of 4,938 tons per year and a deficit of 116 tons - a 2.3% deficit - it’s not difficult to see that the current high prices could encourage enough supply to bring the market back to balance again, even within 12 months.

This story has played out before. There was a massive boom in cocoa prices in the 1970s and another spike in 2008. The latter led to a decline in margins for the chocolate manufacturers, and it took them roughly four years to recover from it. Though even if prices drop, chocolate manufacturers hedge cocoa costs 2-3 years out, so the effect from the cycle tends to be lagged.

Chocolate makers have pricing power and will try to pass on the costs through 5-20% higher chocolate prices. But it typically takes about two years for them to push through price increases to the end customer. And there is also a limit to what customers are willing to pay, especially in emerging markets.

The ICE futures curve is now in backwardation, suggesting lower prices ahead. But the market is not pricing in a recovery to 2022 price levels yet.

To conclude, the cocoa market remains tight, with no fundamental reason to expect prices to drop right now. But, eventually, prices will drop. While surface temperatures are rising most years, 2023 was extreme, and the market will most likely get back into balance within the next three years.

To track the tightness of the cocoa market, I’d suggest looking at the stock-to-grindings ratio. Whenever it goes above 40%, we should expect spot prices to come back to earth.

Also, look at sea surface temperatures on a seasonally adjusted basis. Here, you can see that 2024 temperatures are the highest they’ve ever been, suggesting continued rainfall and weak crops in West Africa. Fundamentals are still strong for cocoa prices and weak for the buyers.

Implications for stocks

Among the traders and processors of cocoa, we find Switzerland’s Barry Callebaut, which deals with 2.3 million tons of cocoa and chocolate yearly. Since Barry Callebaut buys and processes cocoa beans with low margins, it should be hit by the currently high cocoa prices. And the weak share price suggests that its margins are about to get hit by the higher prices.

The chocolate manufacturers have also been affected by the high cocoa prices. Roughly 40% of their cost of goods sold comes from cocoa, split evenly between cocoa beans and cocoa butter. The prices for these two products tend to be highly correlated since they come from the same source. Other, less important expenses for them include sugar and milk.

Other than the cocoa price headwind, manufacturers are also facing weak demand in certain regions, either as a reaction to high prices or to the weight-loss drug Ozempic. The number of Google search queries for “Ozempic” is particularly high in North America, Brazil and Australia. Ozempic seems to be less of an issue for European chocolate consumption.

Most chocolate manufacturers trade at P/E multiples in the mid-teens, with some Asian names like as Delfi and Orion significantly below the average, despite lower exposure to markets where Ozempic is popular, and despite better underlying growth.

Conclusion

Cocoa prices have reached record highs due to rising sea surface temperature, leading to excess rainfall in West Africa and poor cocoa bean crops. Nothing is suggesting that the tightness in the market will be over anytime soon. One will need to follow sea temperatures and the cocoa stock-to-grindings ratio to understand when the tightness eventually gives way to a more balanced market. If history is any guide, the current headwind should be over within three years, even in a worst-case scenario.

While rising cocoa prices lead to higher cost of goods sold for processors such as Barry Callebaut and chocolate manufacturers such as Delfi, they will eventually be able to pass on the higher costs to consumers. That process typically takes about two years. After the 2008 price spike, chocolate manufacturers such as Lindt saw headwinds persist for about four years, potentially due to hedging, which tends to take place 2-3 years out.

Regarding valuations, Asian chocolate manufacturers such as Delfi and Orion trade at lower multiples than in America, even though the impact of Ozempic seems to be much larger than for, say, Hershey. That strikes me as an anomaly. But fundamentals for Asia’s chocolate manufacturers won’t improve until the cocoa question is finally resolved.