Table of Contents

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

- The watch industry has hundreds of years of history, with challenges and technological progress. But people continue to want to tell the time.

- The Apple Watch created significant challenges for the lower end of the market, causing luxury wristwatch brands to focus on the higher end instead.

- The luxury segment also benefitted from China’s credit boom, which now appears to be slowing - especially as speculation in the housing market has cooled down.

- Another key trend is towards watch collecting, which benefits those companies adept at playing that game. Casio has been a master of introducing limited edition models and colourways to get buyers excited. But Swatch Group has also entered the game after orchestrating its successful MoonSwatch collaboration between Swatch and Omega.

- There was a boom in wristwatch sales during COVID-19, which I think was related to the stimulus unleashed during those years. That boom has now turned into a bust, implying lower earnings for the watch retailers that benefitted from it.

When researching watchmaker Casio last year, I dived deep into the world of wristwatches. While challenged by the rise of smartwatches, I became convinced that the industry offers opportunities. For that reason, I’ve decided to provide an overview of the industry: its history, how companies make money and what the future holds for them.

Table of contents:

1. A brief history of watches

2. Recent trends

2.1. Smartwatches

2.2. A polarisation of the industry

2.3. The Swiss monopoly fraying at the edges

2.4. China’s credit boom

2.5. Speculation

2.6. Social media marketing

2.7. Vertical integration

3. The universe of listed watch stocks

3.1. Wristwatch brands

3.2. Wristwatch retailers

4. Conclusion1. A brief history of watches

Let me provide a short history of the industry. In the past, time has been a way to measure the impact of the sun on our lives.

The first attempts to measure time were sundials that used shadows to indicate the progression of time throughout the day:

But the most important innovation was the water clock, which enabled “regulation” - ensuring that each block of time was consistent throughout the day. Much like a modern hourglass, water clocks enabled us to measure time in a uniform, dependable fashion.

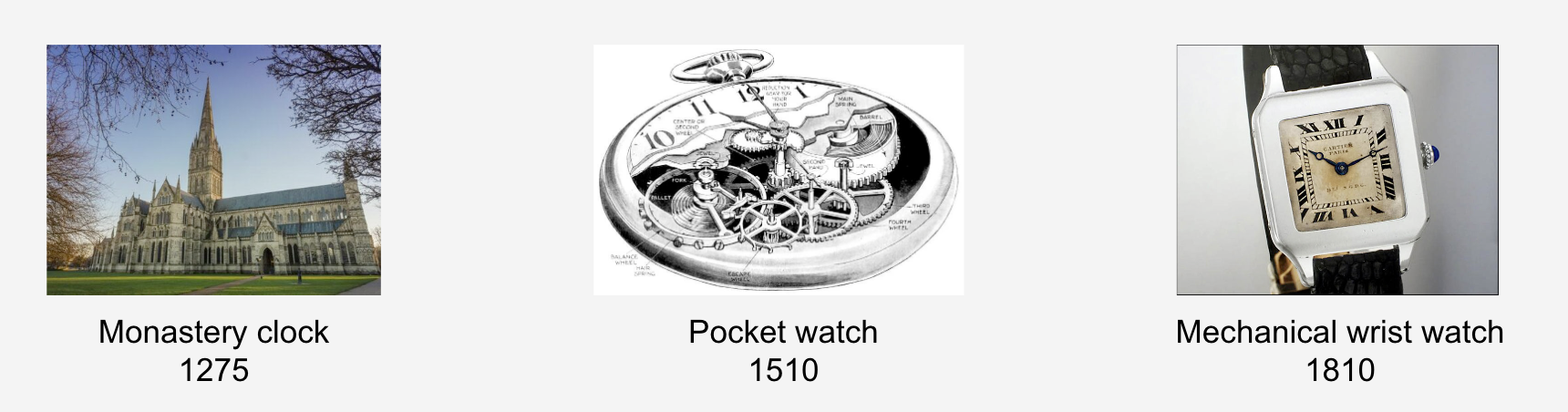

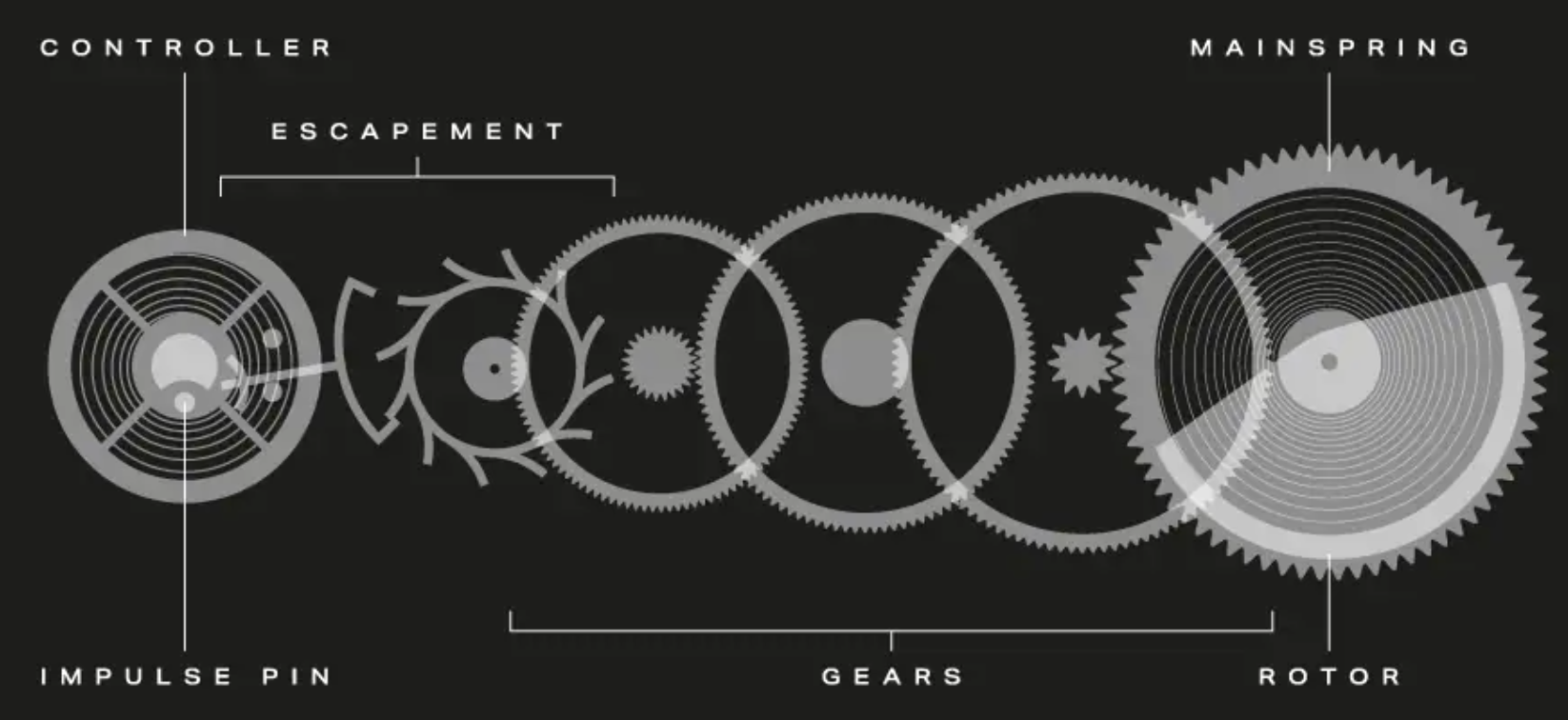

The first mechanical clock was invented in 1275 as part of the Salisbury Cathedral in Britain, and several hundred years later, we got pocket watches worn in the waistcoat for maximum protection. These mechanical clocks worked by letting a mainspring unwound, moving gears throughout connected to hands that would then tick along a 12-hour dial.

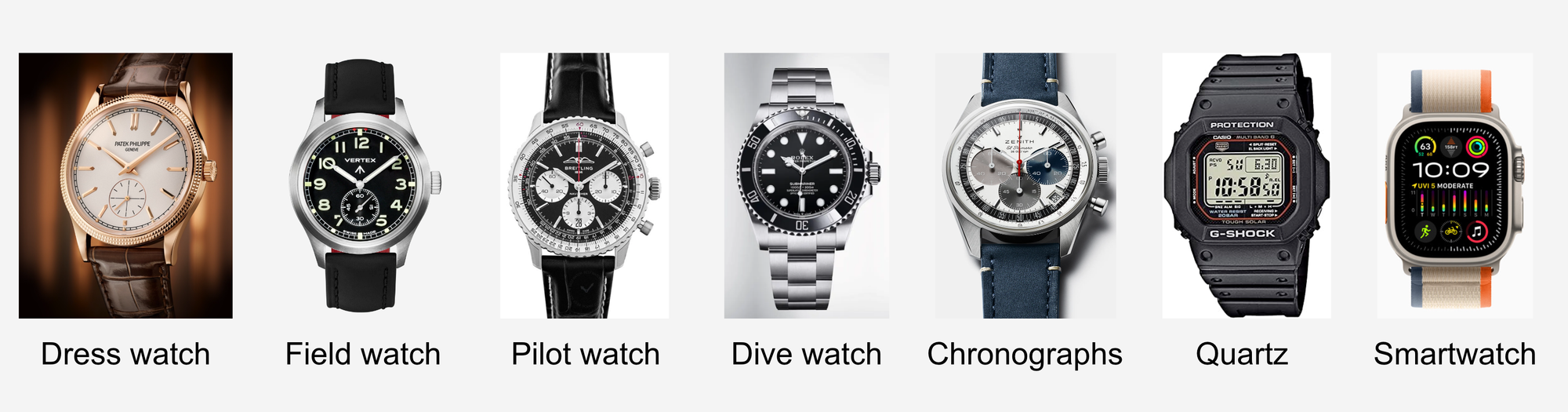

But wristwatches came much later. They were seen as feminine and not suitable for men. The first actual wristwatch was created by Abraham-Louis Breguet for the Queen of Naples in 1810. But it was really a piece of jewellery, a dress watch if you will. In this era, watchmaking moved to Switzerland, specifically in the Vallée de Joux in the Jura Mountains close to Lausanne.

It was a war that popularised the wristwatch for men. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, naval officers started wearing pocket watches on wrists. And then, in World War 1, soldiers started wearing field watches to tell the time while freeing up their hands for combat.

The problem with these early watches is that they had to be wound daily by hand. A revolutionary invention came in 1923 with the invention of self-winding automatic movements. With these, simply by moving your wrist, the watch would charge itself and keep time with little effort for the wearer.

Rolex invented the first waterproof watch in 1926 through its “oyster case”, which prevented water from seeping in. That led to dive watches in the 1940s and 50s, first with the Panerai and then Blancpain and Rolex’s Submariner.

Then, from the late 1960s onwards, we saw the first automatic chronographs, which are used to time events like car races. Examples include the Zenith El Primero, Rolex Daytona and Tag Heuer Monaco.

A major shift in the industry was the invention of the quartz watch in the 1960s and the popularisation of it by the Seiko Astron in 1969. These quartz watches replaced the mechanical movement with a battery-driven mechanism that used quartz crystals to create a periodic thrust on the watch hands.

In the following 15 years, these cheap and reliable quartz watches caused a crisis for the Swiss watch industry. The number of Swiss watchmakers dropped from 1,600 to just 600. In 1983, the two biggest Swiss watch groups, ASUAG and SSIH, merged to form Swatch Group in a last attempt to save the industry. Even James Bond started wearing a digital watch.

Swiss mechanical watches staged a comeback by becoming luxury items. Swiss watch exports grew strongly up until the early 2010s.

More recently, the watch industry has faced some challenges. One such challenge was Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign in 2012. At that time, the Chinese government banned using public funds to purchase luxury goods.

The second challenge came in 2015 with the “Apple Watch” smartwatch. Its key selling point was health & fitness tracking and the ability to check messages. On the other hand, it required daily charging. It’s become a major success, taking market share from the lower end of the luxury wristwatches, the segment around CHF 1,000 and lower.

And some even question whether we need to wear a watch in the first place when we can tell the time perfectly fine on our smartphones. Technological progress if forcing the industry to evolve.

2. Recent trends

2.1. Smartwatches

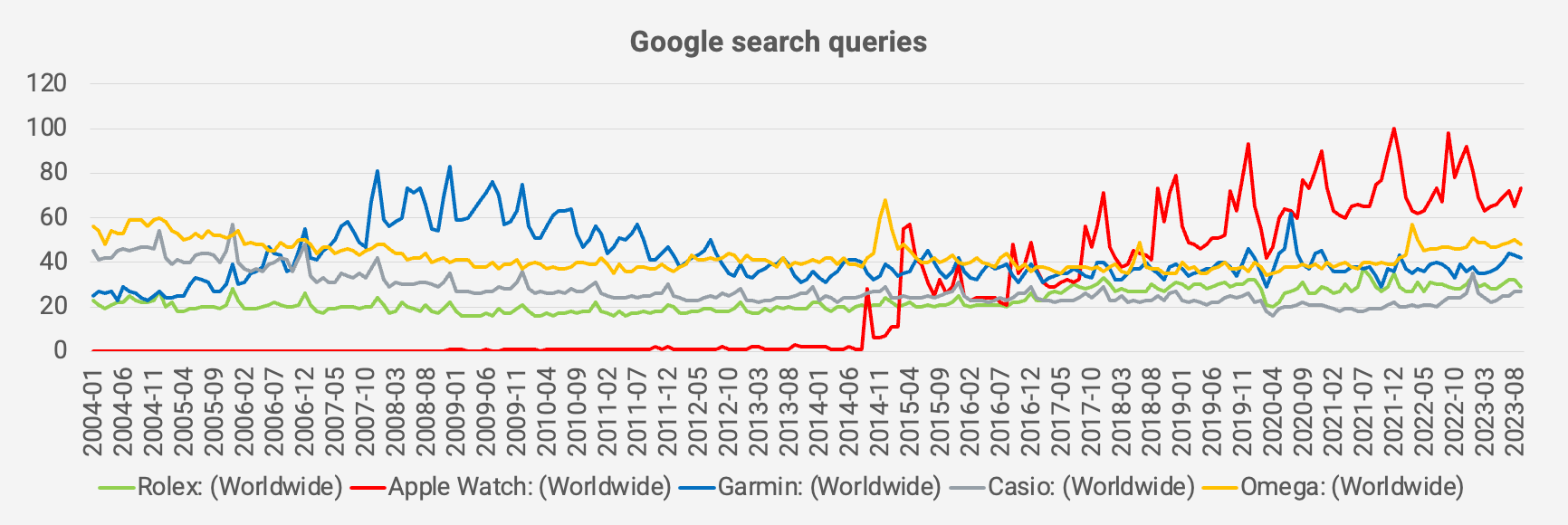

Today, smartwatches continue taking market share as they become more capable. An index of the number of Google search queries for the Apple Watch is now higher for the Apple Watch than any of the major watch brands: Rolex, Omega, Casio and others:

Around 40 million Apple Watches are sold each year. Not much compared to the total production of 1.2 billion watches, but significant compared to the 20 million or so higher-priced watches exported from Switzerland each year.

What’s the appeal of the Apple Watch?

- First of all, it’s stylish. Wearing a watch is not all about status; it’s also about showing your good taste and being up-to-date on the latest trends. Potential partners might assume that a person who pays attention to clothing will also pay attention to other parts of his life, including his relationships and career.

- Another appeal of the Apple Watch is its functionality: the feeling of control, being able to glance at calendar events or messages by just raising your hand.

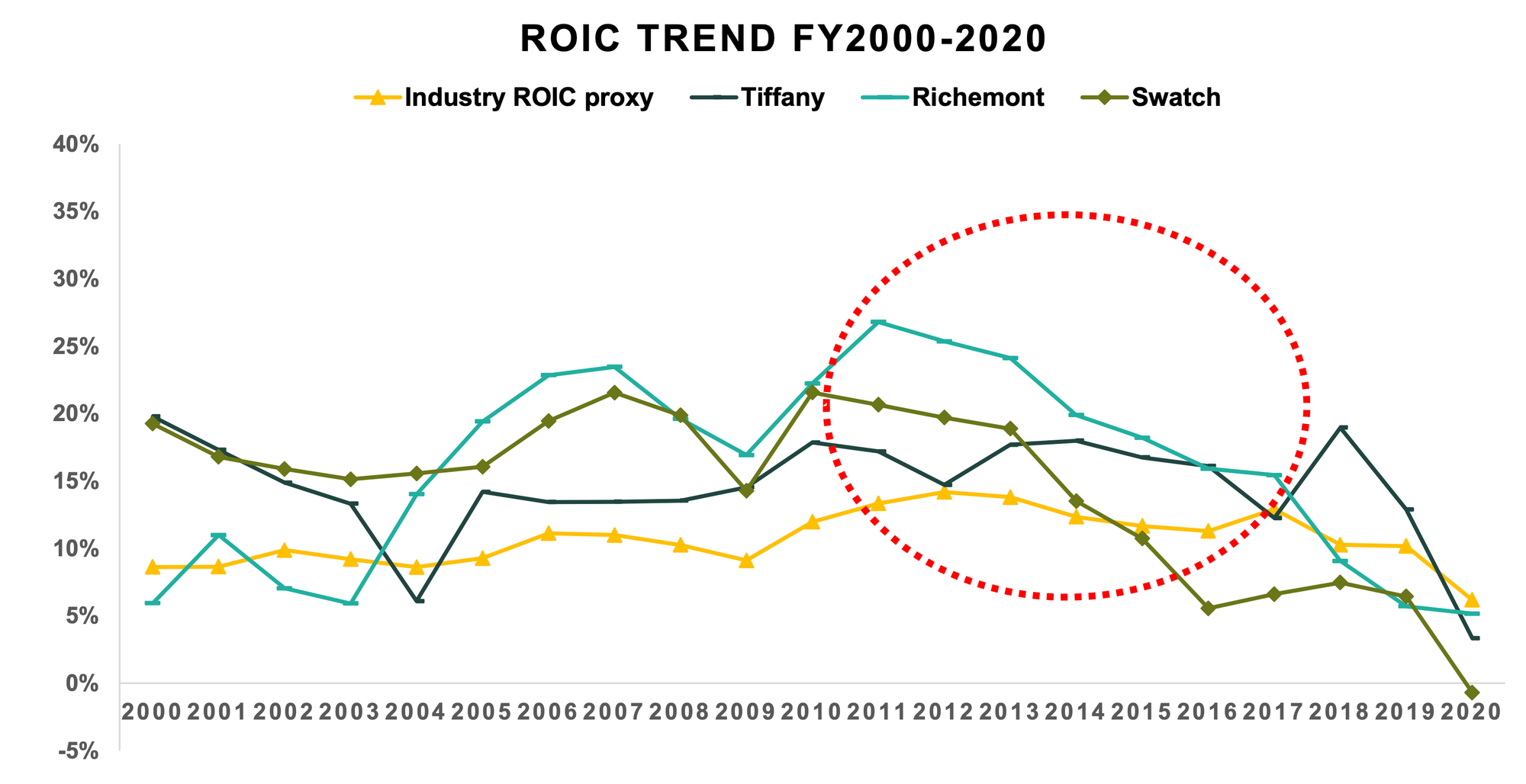

Another way to illustrate the Apple Watch's challenge on the industry is the return on invested capital (ROIC) by the largest companies in the industry. Pure-play watchmakers Richemont and Swatch have both seen their ROIC fall, but especially Swatch, given its larger exposure to the entry-level segment.

And other fitness trackers are popping up as well. Garmin running watches, Fitbit fitness trackers, Oura rings and Whoop bands also take wrist space from competing wristwatches.

2.2. A polarisation of the industry

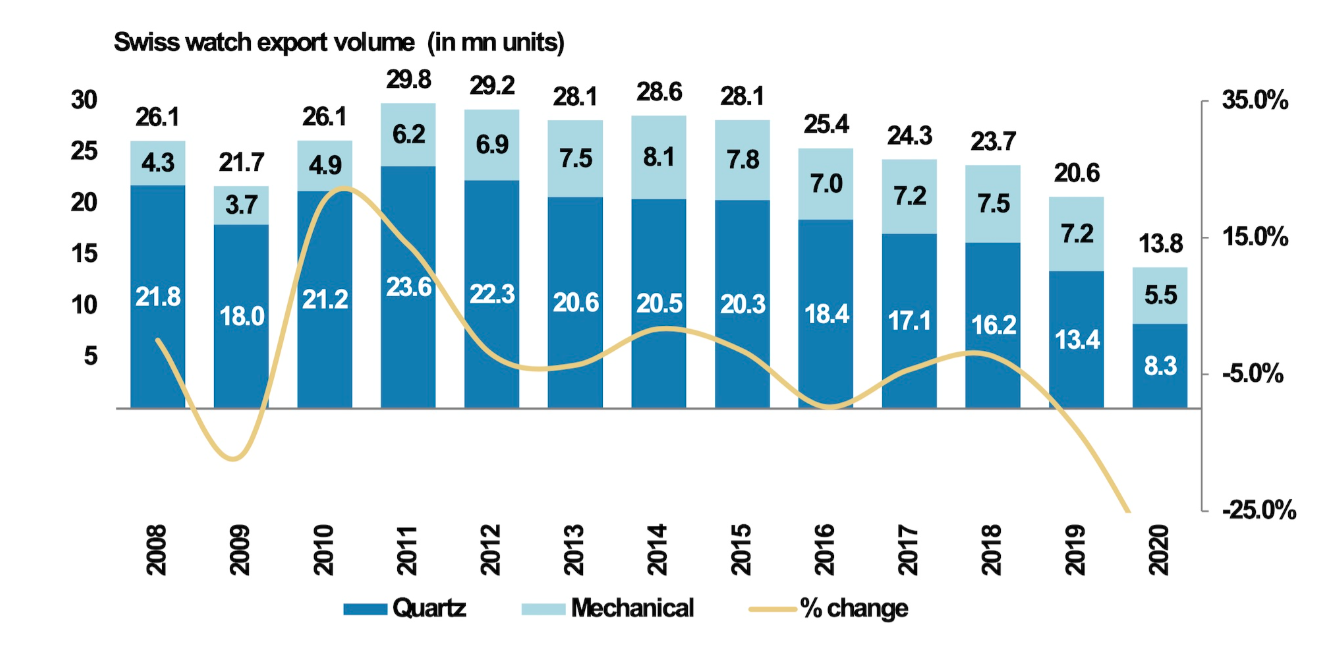

Even since the Apple Watch was released in 2015, Swiss watch export volumes have been in structural decline:

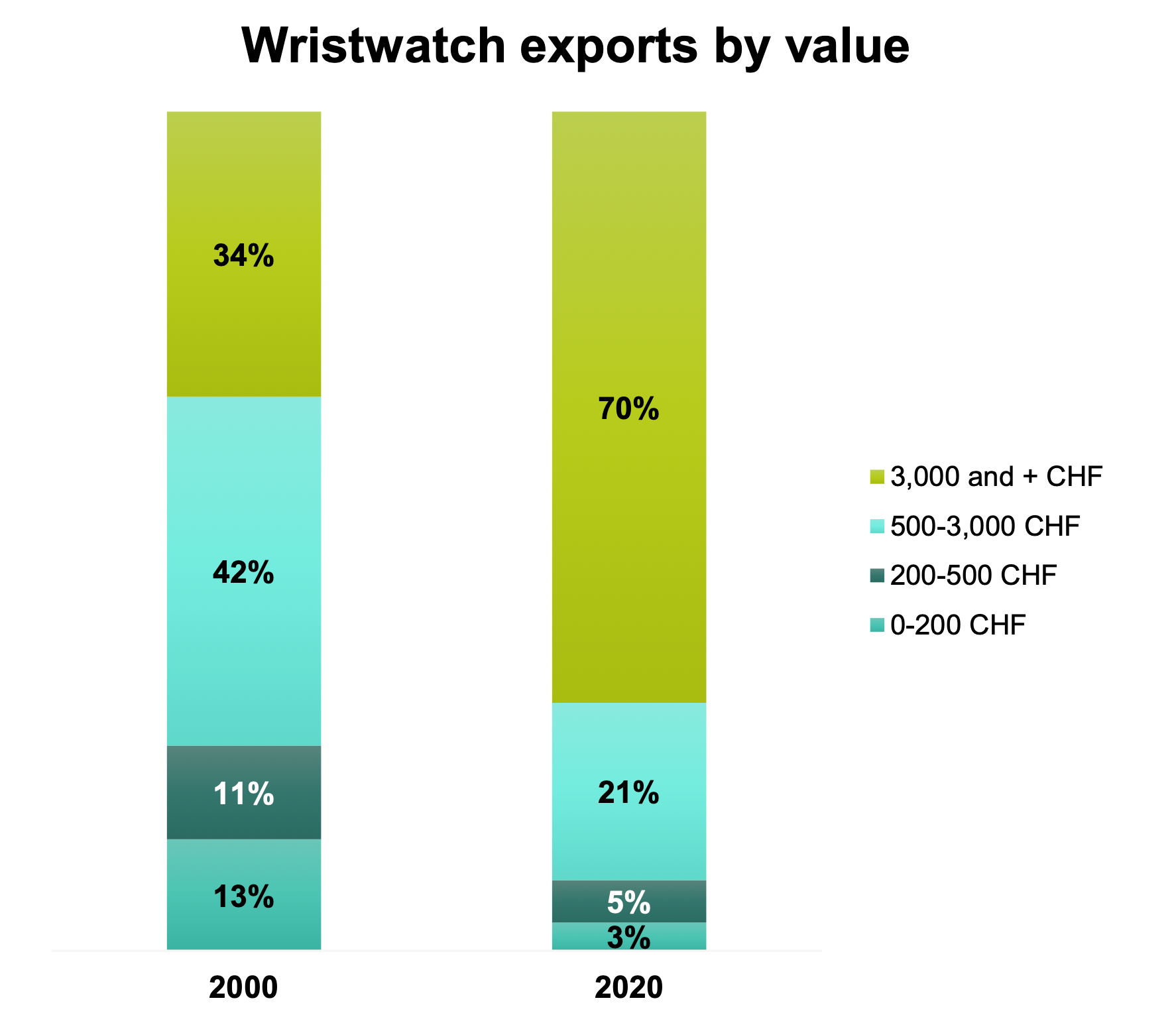

And the data is clear: it’s mostly the lower-end watches that are suffering from this new competition. Here’s a chart from Bernstein showing how the Swiss luxury watch market has shifted from mid-priced watches to luxury.

At the lowest end of the market, you have low-maintenance quartz watches produced by the likes of Casio, Timex and Titan. And at the higher end, you’ve got the likes of Rolex and Omega trying to sell watches not as necessities but rather luxury products. This is the polarisation I’m referring to. The middle segment is essentially dying.

Why would anyone spend thousands of dollars on a luxury wristwatch? Usually to signal status or as a marker of achievement. We want to feel special. And since most mechanical wristwatches are made by hand, they will continue to be expensive and perceived as such.

At the same time, the industry will remain fragmented since there is no universally perfect solution to the problem of telling time. Apple Watches are technologically impressive but require daily charging. Quartz watches offer less functionality but require close to zero maintenance. And while mechanical wristwatches offer sex appeal, they’re usually not as accurate as their much cheaper quartz alternatives.

The largest Swiss watch brands have shifted their approach to adapt to this new reality. Companies like Rolex have started increasing their prices at nearly 2x GDP growth and introducing more luxurious materials. They’ve started to manage the supply of watches actively to avoid discounting and maintain a perception of exclusivity. And they’ve also started to play up their heritage through clever storytelling.

Such story-telling usually brings out older iconic models from the back catalogue and explains why they’re special. Such vintage reissues have become popular in the past few years, with Longines, Tudor and Seiko focusing on such campaigns.

The trend towards smaller watches below 40mm case sizes is also part of this strategy of returning to the past. Buyers deserting the Apple Watch tend to want something different, and vintage reissues promise them a different value proposition, a return to simpler times.

2.3. The Swiss monopoly fraying at the edges

Luxury wristwatches are still mostly produced in Switzerland, especially in the higher-priced category. Swiss watchmakers created the industry in the 19th century, with brands such as Patek Philippe, Longines and Rolex becoming industrial powerhouses in the early 20th century.

Within Europe, Switzerland is facing competition from Germany. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the watch factories in the East German town of Glashütte were revived, leading to the rise of German brands like A. Lang & Söhne, Nomos and Glashütte Original.

And East Asia is taking market share as well. The “Swiss Made” label only means that 60% of the components were produced in Switzerland. The rest usually come from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

From the 1960s onwards, Japanese watchmakers like Seiko and Casio seized upon the opportunity presented by quartz watch innovation by taking market share in the lower-end segment. Today, Seiko is muscling into luxury wristwatches through its well-regarded Grand Seiko brand.

The big question now is whether Chinese brands can undercut Swiss and Japanese competitors through manufacturing prowess. For example, former state-owned watchmaker Tianjin Seagull has started to produce mechanical watch movements directly competing with Swatch Group’s movement manufacturer ETA, though with poor accuracy.

2.4. China’s credit boom

Some argue that there’s a correlation between M2 money supply and the consumption of luxury goods. I haven’t seen hard data to prove this point. The intuition is this: when a new loan is issued, wealth is concentrated into the hands of the few, enabling the purchase of high-ticket items like wristwatches.

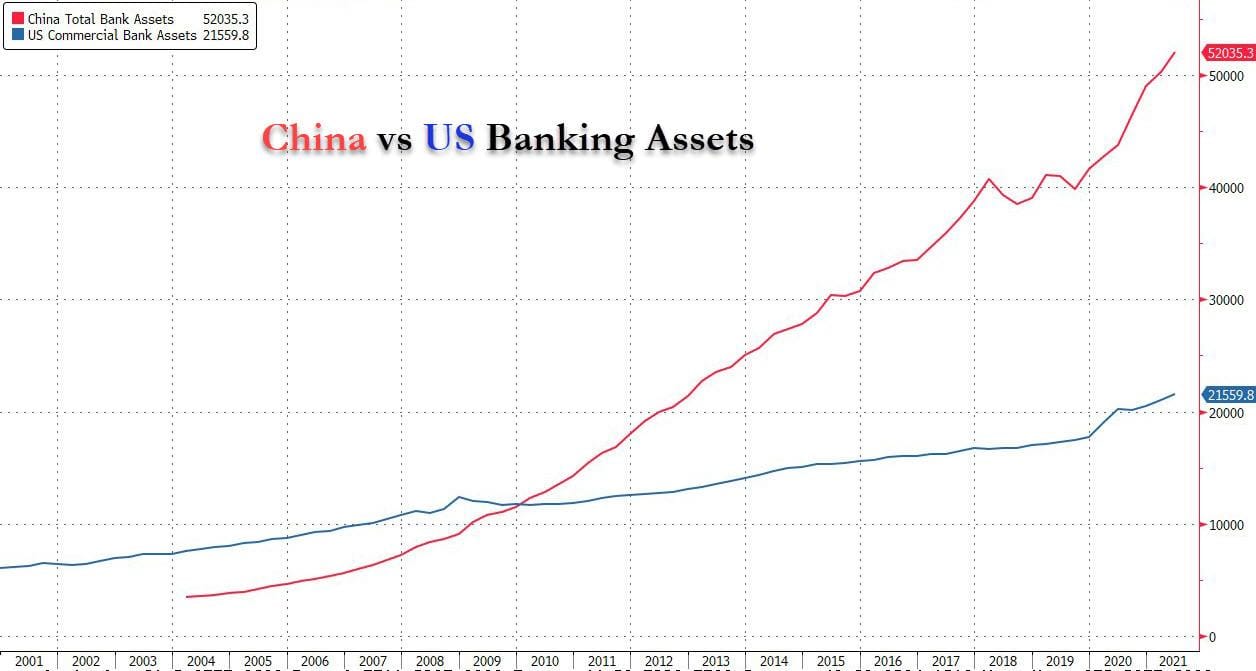

Growth in the money supply could explain the boom in luxury goods consumption in China in the past 10-15 years. In the past 20 years, Chinese banking assets have increased by over 10x.

A 2013 Beijing-based Fortune Character Institute survey suggested that 46% of all luxury goods sales globally were to Chinese individuals. The ratio between luxury goods consumption and GDP has also been out of whack for China. Not unlike Japan in the late 1990s when that country had represented roughly 25% of global sales.

It’s possible that some of these purchases of luxury wristwatches were done to funnel capital out of the country. Experts say that Rolex is so popular among mainland Chinese because they consider it equivalent to cash, given the liquid second-hand market for Rolex watches. If you travel with a Rolex watch to Hong Kong, you can easily sell it on the second-hand market and convert the proceeds to the US Dollar.

The government is clamping down on this practice, though, by making it more difficult to purchase high-priced luxury goods items and also making it more difficult to bring them across the border.

Weakness in China’s property market now puts the credit growth story in question. Most state-owned enterprises are already over-levered, and private companies in China no longer have much access to credit. Meanwhile, households remain relatively indebted. And home prices are already expensive, at least in tier 1 cities.

2.5. Speculation

There’s been a bubble in the luxury wristwatch market in recent years. I believe it was caused by cash handouts given out during COVID-19.

Indices of second-hand prices for luxury wristwatches like those from Rolex almost doubled into 2021 before deflating again:

In 2021, some shoppers started seeing watches as inflation hedges or investments. It reminds me of similar trends for Moutai rice wine, vintage cars and art. An index of Google search queries for watch investing peaked in late 2020 and has now returned to normal levels.

The bubble is deflating. At the bubble's peak, the waiting time for the privilege of buying a Rolex increased to 2-4 years and has returned to just 3-4 months.

I believe that the bubble episode caused dealer profits to become unsustainably high:

- Some authorised dealers convinced potential buyers of sought-after Rolex Daytonas or Patek Philippes to buy lower-priced items first to get ahead in the queue.

- There are also signs that some perhaps authorised dealers might have resold watches directly to the grey market, capturing some of the spread between the MSRP and the second-hand market price.

Whatever the reason, it’s plausible that the bubble boosted watch dealer profits. They might have resold watches to the grey market or just pushed consumers to buy watches to qualify for waitlists.

It’s also plausible that consumers have been speculating on watches in the hope of near-term gains. Such momentum-buying tends to dry up in the down phase of any speculative episode.

2.6. Social media marketing

Young people in the developed world have almost entirely stopped watching TV. Instead, eyeballs are flocking to YouTube and platforms like Bilibili. The number of monthly active users on YouTube is now nearing 3 billion people.

I think this shift is having an immense impact on how consumers make purchase decisions regarding watches. They take cues from influencers on Instagram, TikTok or YouTube.

These days, brands send watches to influencers for “review”, hoping the products will go viral. And maintaining relationships with these influencers becomes crucial for brands’ marketing efforts.

I also believe that social media marketing has created a boom in watch collecting. A Google search query index for watch collecting has increased significantly in the past three years.

Collectors are motivated by the thrill of the hunt - seeking a dopamine hit as the collection approaches completion. Acquiring a watch provides a sense of accomplishment. The concept of hedonic adaptation suggests that once a collector obtains a coveted piece, dopamine will return to baseline levels, requiring him or her to continue collecting to achieve the same level of satisfaction. Collecting is a never-ending pursuit.

And it’s not just rich individuals collecting. The success of Swatch’s Moonwatch collaboration and the ever-increasing colourways of Casio G-Shocks show you that the collecting trend is also starting to show up in the sub-CHF 500 category.

2.7. Vertical integration

Rolex’s acquisition of watch retailer Bucherer a few weeks ago took the industry by storm. Rolex has traditionally only been a watchmaker, relying on authorised dealers to distribute its watches. However, acquiring Bucherer marks a shift in Rolex’s strategy, potentially moving towards vertical integration.

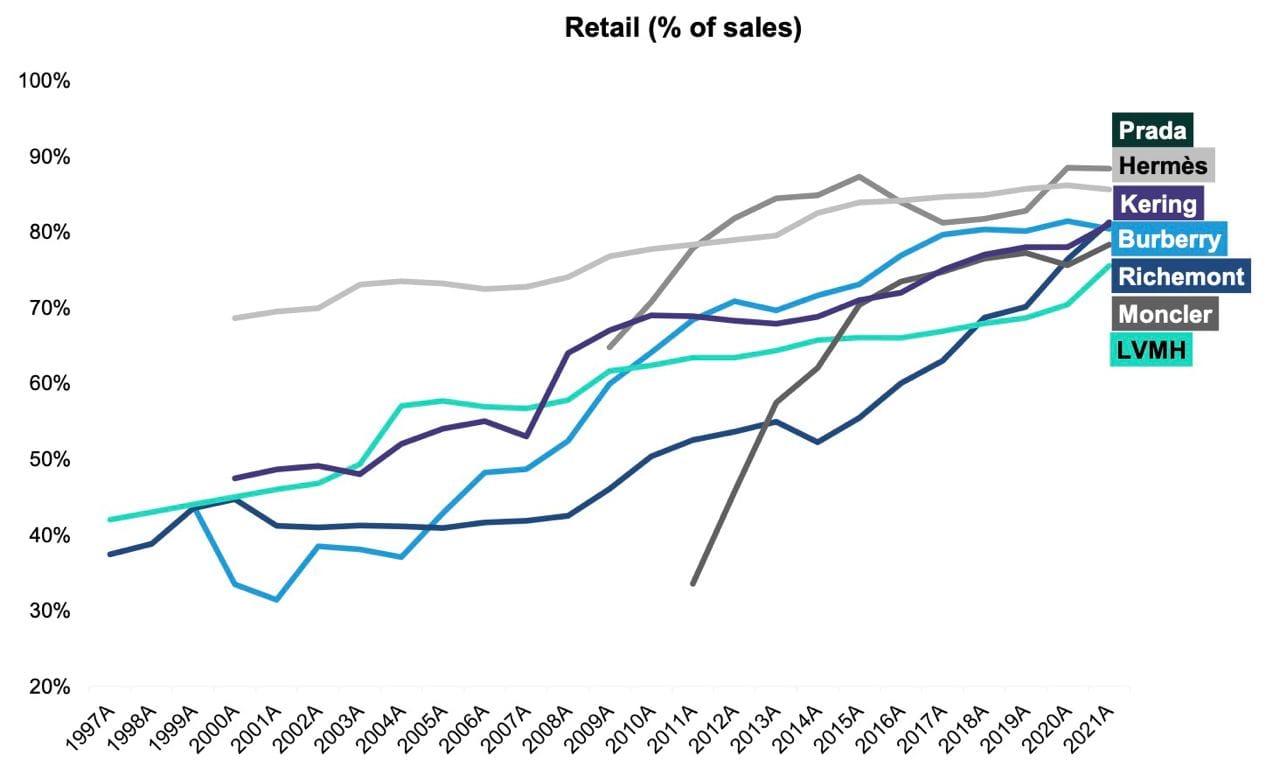

In the luxury goods industry, vertical integration has been a long-term trend pioneered by LVMH, Richemont, etc.

Why are we seeing this trend? Partly because price discipline helps maintain a perception that a product is valuable, difficult to obtain and scarce.

In psychology professor Robert Cialdini’s best-selling book Influence, he made the point that consumers value a particular item more if it’s perceived to be scarce. We’re particularly attracted to scarce resources when competing with others for them. And we feel special when we obtain them.

Today, watchmakers are trying to unify prices across wholesale channels when there's instant price discovery online. But that’s difficult unless you control distribution via your website or fully operated offline stores.

The need to control prices is why Richemont bought back inventory from the wholesale after Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign from 2012 onwards. Discounts would have ballooned without these buybacks, hurting brand perception.

3. The listed universe of watch stocks

So, how can companies stand out and win in the industry? In my view, there are a few levers to pull:

- First, they need to create stories around iconic, distinctive watch models that can help build a perception of scarcity. They need marketing that brings images, memories or feelings to mind. The Omega Moonwatch is marketed as the first wristwatch worn on the moon. Stories like this make consumers think their watch is special - something they should treasure.

- Second, to maintain that scarcity factor, brands have to tread carefully by actively managing the supply of watches in the retail and wholesale channels. This includes not stuffing the wholesale channel and controlling inventory through extensive data collection.

- Third, by controlling the shopping environment by building beautiful stores and shopping experiences, companies can improve the perception of brands in the eyes of consumers.

The company that’s done best at achieving these four factors is undoubtedly Rolex and its sister brand, Tudor. The Rolex brand name has enormous consumer mindshare the world over. Supply has historically been managed well. They operate through a system of authorised dealers that control the shopping experience.

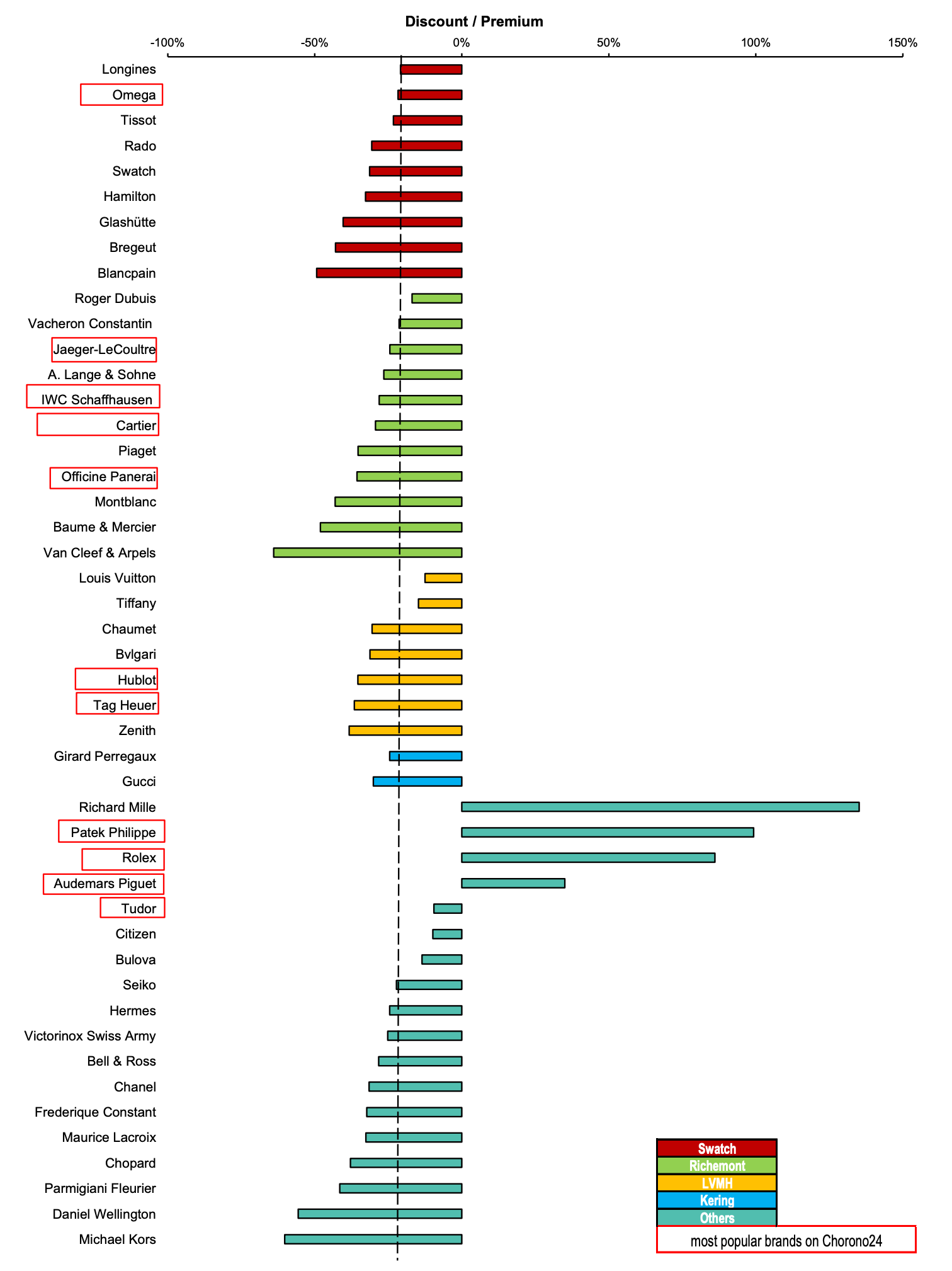

This chart from Bernstein, with data from Chrono24, shows the discounts vs. premiums that different brands enjoyed in the second-hand market in 2021:

As you can tell, Rolex is one of the few brands that traded at a premium, together with Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet, which sells the Royal Oak luxury wristwatch. Most other brands, such as those by Swatch and Richemont, are sold at deep discounts in the secondary market, suggesting weaker brand perception.

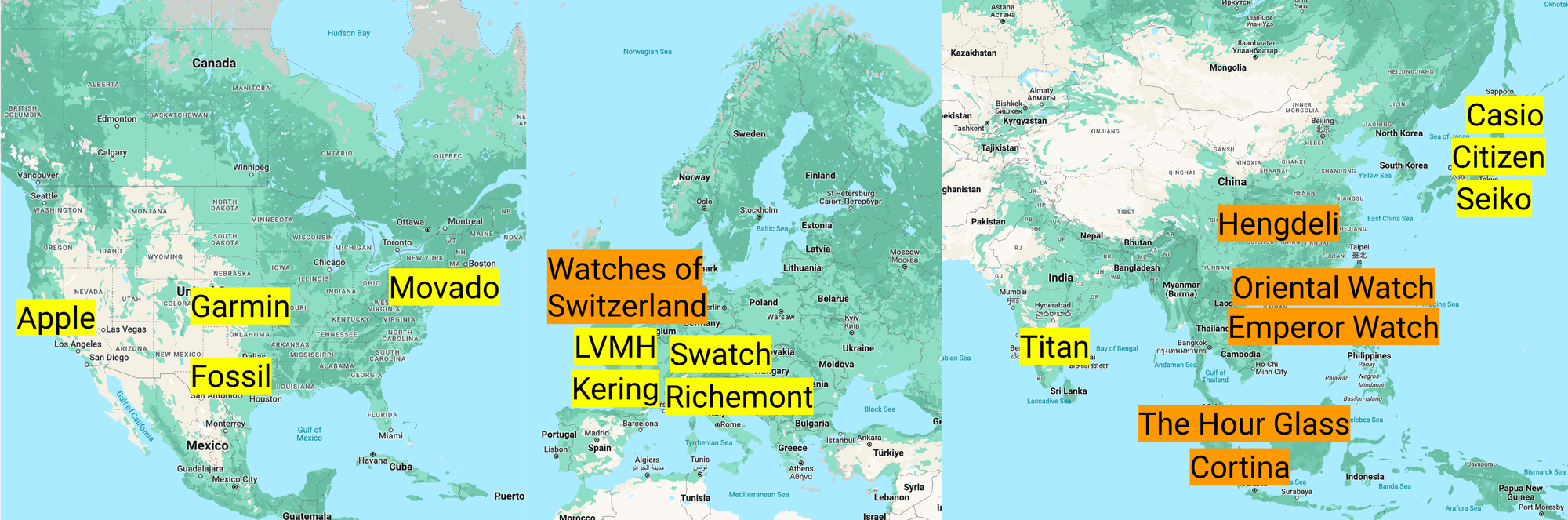

The luxury wristwatch makers in the chart above are mostly based in Europe, with Swatch and Richemont listed in Zurich, LVMH, and Kering in Paris.

In the United States, you have several tech-focused watchmakers, including Apple, Garmin and Fossil. In Japan, Casio, Citizen and Seiko tend to be more focused on quartz watches, but Seiko, in particular, is also moving into higher-end mechanical wrist-watches. India’s Titan produces watches primarily for the local market.

Meanwhile, most of the listed watch retailers are based in either Hong Kong or Singapore, cities with historically low sales tax and a large concentration of wealth.

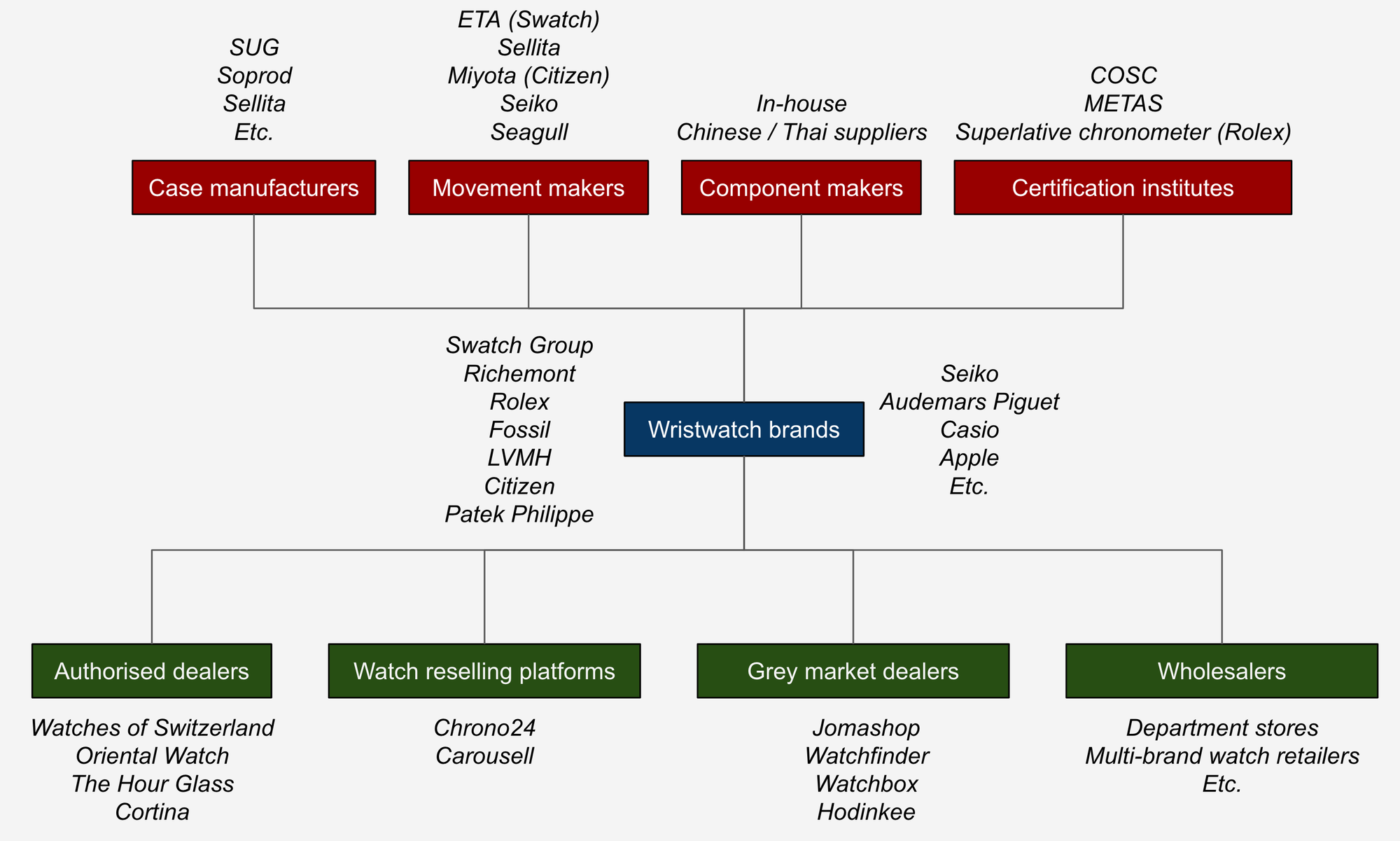

The supply chain is simple, with many components produced in-house among the larger groups:

Mechanical wristwatches are typically assembled by hand in Switzerland, while the manufacturing of quartz watches tends to have a greater degree of automation.

Mechanical wristwatch movements are often produced by third-parties, such as Swatch-owned ETA or Citizen-owned Miyota. These movements are sometimes modified by the purchaser and then combined with cases, dials, and bracelets to create a watch.

Outsourcing the manufacturing of movements to ETA saves on cost but also commoditises the product.

Meanwhile, certification institutes like COSC and METAS help ensure regulation, i.e., that watches are accurate within certain parameters.

Distribution typically occurs through authorised dealers, the wholesale market, or multi-brand watch retailers. Authorised dealers work with specific brand names, getting privileged access to watches in return for maintaining high professionalism and price discipline. However, authorised dealer contracts can be revoked at any time, making the value of their cash flow streams uncertain.

Thanks to the Internet, we now have online watch reselling platforms like Chrono24 and Carousell. As well as grey market dealers such as Jomashop or Shopify stores run by Instagram or YouTube watch influencers.

The raison d’être for these grey market dealers is that they can arbitrage differences in prices and taxes across regions and help brands eliminate excess inventory. Though at the risk of hurting the brand.

3.1. Wristwatch brands

The titans of the wristwatch industry are Rolex and Patek Philippe. However, neither of these are publicly listed companies.

The largest listed entities have not performed as well in the competition with the Apple Watch. For example, Richemont (CFR SW - US$74 billion) has an incredible stable of brands, including Cartier, Panerai, Vacheron Constantin, IWC, Jaeger-LeCoultre Mont Blanc, A Lange & Söhne and more. After its 2008 spin-off of British America Tobacco, Richemont is almost exclusively focused on jewellery and wristwatches. However, its return on equity remains barely higher than the cost of capital.

The Swatch Group (UHR SW - US$14 billion) was formed through the merger of two major Swiss watchhouses that failed in the early 1980s after the quartz crisis and were revived by Nicholas Hayek through the 1980s and 1990s. Its ownership of movement maker ETA provides a competitive advantage, though it has recently lost market share. It owns Omega, Longines, Tissot, Hamilton, Blancpain, Glashütte Original, Rado, Certina, etc. It’s lost market share in recent years due to its exposure to products at similar prices to the Apple Watch, but it’s had recent success with the marketing of its new MoonSwatch collaboration.

There are also several fashion houses owning wristwatch brands. Bernard Arnault’s LVMH (MC FP - US$393 billion) entered the watch industry by acquiring Zenith, Tag Heuer, Hublot and Bulgari brand names from 1999 onwards. Kering (KER FP - US$57 billion) owns Ulysse Nardin and Girard-Perregaux, two watch brands that are not particularly relevant in consumers’ eyes. But through its ownership of Gucci, Balenciaga, Bottega Veneta, etc., it’s achieved a return on equity at the top of the industry.

In the smartwatch category, you have Apple’s (AAPL US - US$2.7 trillion) Apple Watch, which dominates the industry with its smartphone compatibility and vivid OLED screens. Kansas-based Garmin (GRMN US - US$20 billion) used to produce navigation systems for vehicles, before pivoting into smartwatches in the past ten years with great success. Other American watch brands like Fossil (FOSL US - US$115 million) and Movado (MOV US - US$594 million) are struggling.

Japanese watchmakers were hit hard by this new competition from the Apple Watch. Seiko Group (8050 JP - US$14 billion) is perhaps the most well-known watch manufacturer in Japan, selling watches under the Seiko as well as the Grand Seiko brand names, increasingly moving upmarket as brand recognition has improved. Citizen Watch (7762 JP - US$1.6 billion) has been selling cheap quartz but reliable watches in the past few decades and, therefore, has been hit hard by the smartwatch trend. The brand recognition is not nearly as strong as with Seiko’s. Ownership of movement maker Miyota provides a competitive advantage. Casio (6952 JP - US$2.1 billion) is most known for its G-Shock line of rugged digital watches, which, in my view, dominate the lowest end of the watch market. It’s also been adept at appealing to collectors with an ever-increasing variety of G-Shock colourways and material choices. I wrote about Casio in October 2022 here:

I’m personally seeing continued growth at Apple and Garmin if and when they introduce new features to their products, including continuous glucose monitors and better battery life.

In line with my view of the increasing polarisation of the market, I also think that luxury brands such as Rolex, Tudor, Moser, Patek and others will continue to do well thanks to regular price increases.

At the other end of the market, I think Casio will survive by dominating the lower-end niche and appealing to collectors. Whether the company will grow in absolute terms is another question, though. Due to China's zero-COVID policy, Casio trades at a high multiple but against a low base.

Some believe the “MoonSwatch” collaboration between Omega and Swatch diluted the Omega brand name. But one could also argue that Swatch Group is finally starting to appeal to the collector’s market. Rising Google search queries for the Omega brand indicate a potential turnaround. Swatch Group now trades at a forward P/E of 13x.

I also think that Grand Seiko will continue to take market share. Grand Seiko's manufacturing prowess is up there with the top Swiss brands, at least regarding dial complexity. Seiko Group Corporation now trades at a P/E of 12x and benefits from the weak yen.

However, the return on equity for the Swatch Group, Casio and Seiko are not impressive. Certainly not in comparison to the French luxury houses Kering and LVMH. Bigger changes to their corporate strategies would be needed for them to compound capital at truly high rates.

3.2. Wristwatch retailers

Wristwatch retailers are essentially middlemen between brand owners and customers. They add value by service execution and lowering the customer's purchase risk. If you buy through Torneau or Oriental Watch, you can be sure you’re buying an authentic product. And if something happens to the watch, you know where to get it fixed.

But watch retailers must manage their relationships with brands, which is easier said than done. Break Rolex’s trust and your entire business model is at risk. Therefore, watch retailers' economic moats are not nearly as strong as the brands' owners.

Retailers benefitted from customer largesse during COVID-19, when many households received direct cash payouts from their governments. On the other hand, borders were shut, making it difficult for Chinese to visit Hong Kong or Singapore to buy watches.

Singapore’s watch retailers might benefit from capital and individuals moving from Hong Kong and mainland China to Singapore. We can observe this flow of capital through Singapore’s FX reserves, which rose from 2019 onwards.

I only found one listed wristwatch retailer in Europe: the UK’s Watches of Switzerland (WOSG LN - US$1.8 billion). It offers the typical luxury wristwatch brands such as Rolex, Patek Philippe, Omega, Cartier, etc. In Hong Kong, you’ll find Rolex dealer Oriental Watch (398 HK - US$265 million), Emperor Watch (887 HK - US$155 million), Citychamp Watch & Jewellery (256 HK - US$639 million) and China’s Hengdeli (3389 HK - US$107 million).

I don’t think valuation multiples are helpful indicators for watch retailers right now since their earnings might not be sustainable, boosted by the watch market bubble we observed from 2020 onwards. It is unclear whether their high profitability was driven by stock market gains, crypto speculation, or high second-hand prices for luxury wristwatches. But in any case, the bubble has probably not deflated entirely just yet.

Regarding the listed watch retailers, I’m personally treading with extreme caution. But I’m keen to cover Singapore’s listed watch retailers sometime soon.

4. Conclusion

Most of the impact of the Apple Watch has already been felt. But one cannot rule out innovation that will further impact the lower end of the watch market. Some companies, such as Casio and Swatch Group, may be able to counter this challenge by appealing to collectors.

But otherwise, the watch market faces continued pressure to move upwards in price. And for that, you need to manage brand names skillfully. Rolex and Patek Philippe are among the only companies that have achieved strong brand perception and pricing power.

Speculative activity and an unsustainable boom in watch purchases benefitted the listed watch retailers during COVID-19. We’re now seeing the tail end of that boom. There’s also a risk of Rolex starting to compete with them now that it’s started to get into retailing itself. That said, watch retailers such as Hour Glass and Cortina have been highly profitable across the cycle and might be worth covering in the future.

If you would like to support me and get 20x high-quality deep-dives per year and other thematic reports like this, try out the Asian Century Stocks subscription service - all for the price of a few weekly cappuccinos.