Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

I am not a macro prognosticator, so take the following discussion with a grain of salt.

But lately, I’ve been asking myself what might happen to the Japanese market if the currency ever strengthens.

The Japanese yen has gone through many such cycles of weakening and strengthening against the US Dollar. And it’s now hitting the upper limits of its historical trading band, having depreciated more than 30% against the dollar since 2021:

This weakness has been driven by widening interest rate differentials in the US and Japan, where short-term US deposits offer more than 5% compared to not much more than zero in Japan. Capital has flowed out of Japan to take advantage of this opportunity.

What caught my eye the other day was this chart, showing a tight correlation between the US 10-year government bond and the USDJPY exchange rate. The higher US yields go, the weaker the yen tends to become.

The trillion-dollar question now is whether the interest rate differential will narrow at some point, causing the yen to strengthen - either through lower interest rates in the United States or higher in Japan.

Table of contents

1. Why the USD-JPY interest rate differential might narrow

2. Prior episodes of yen strengthening

2.1. The Great Financial Crisis precedent

2.2. The Asian Financial Crisis precedent

3. Potential strong yen beneficiaries

4. Conclusion1. Why the USD-JPY interest rate differential might narrow

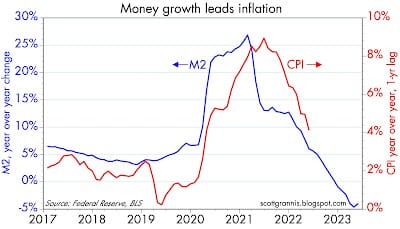

Economist Scott Grannis at the Calafia Beach Pundit blog likes to show the following chart about how the US M2 money supply growth has been a leading indicator of the year-on-year change in CPI since the pandemic began in 2020.

While the fiscal deficit on a federal level is edging towards 8% yet again, the private sector is deleveraging, causing the above contraction in the aggregate money supply.

Logic tells us that if interest rates are higher than the income growth of the average borrower, debt will accumulate. And borrowers will be less keen on taking on new debt.

That’s why I think it’s meaningful that with BBB spreads of 1.6%, total borrowing costs for an average corporate US borrower will be above 6%. And for individual borrowers, 30-year mortgages now cost 7%.

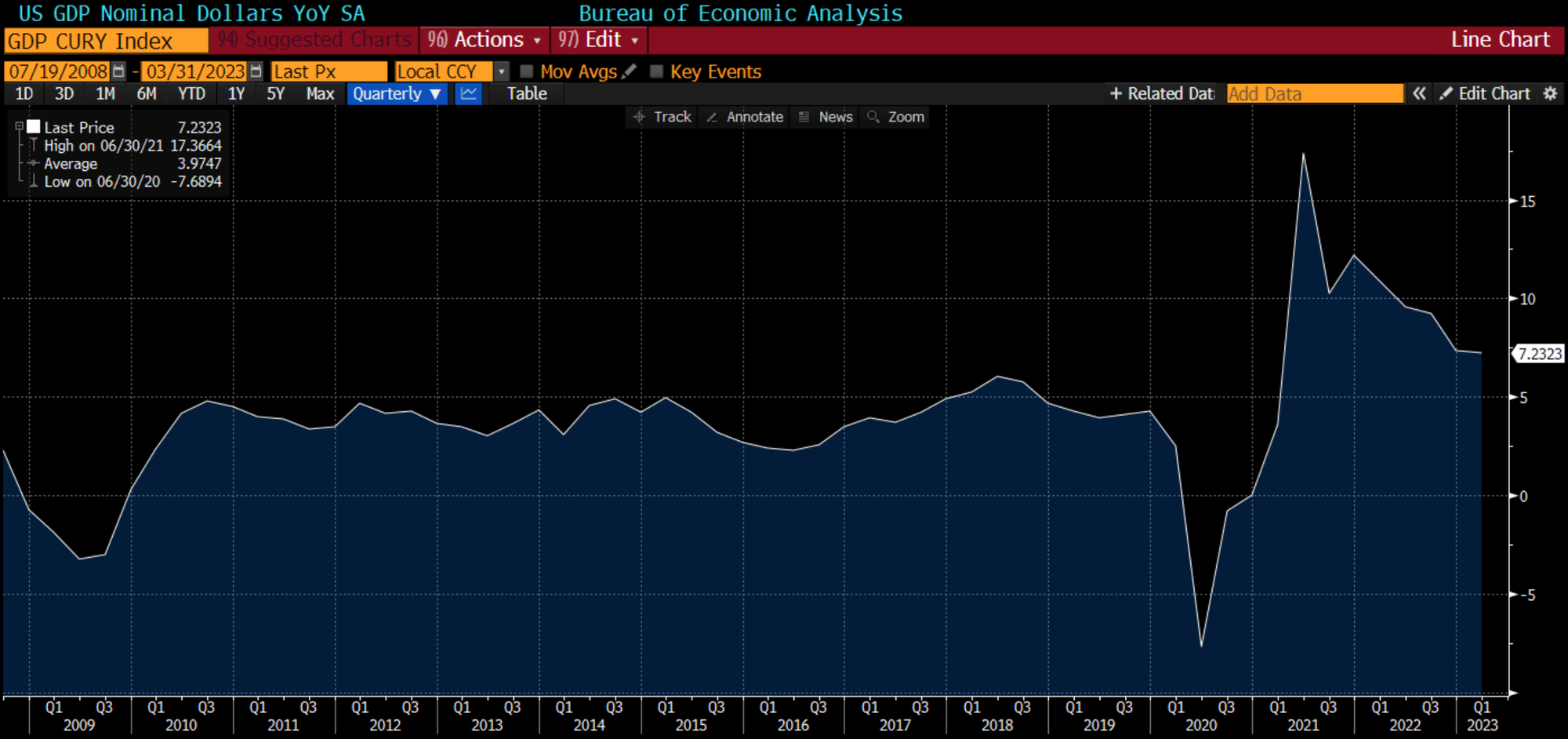

These are very high levels compared to the pre-COVID nominal GDP growth of around 4% per year. US interest rates are very high, indeed.

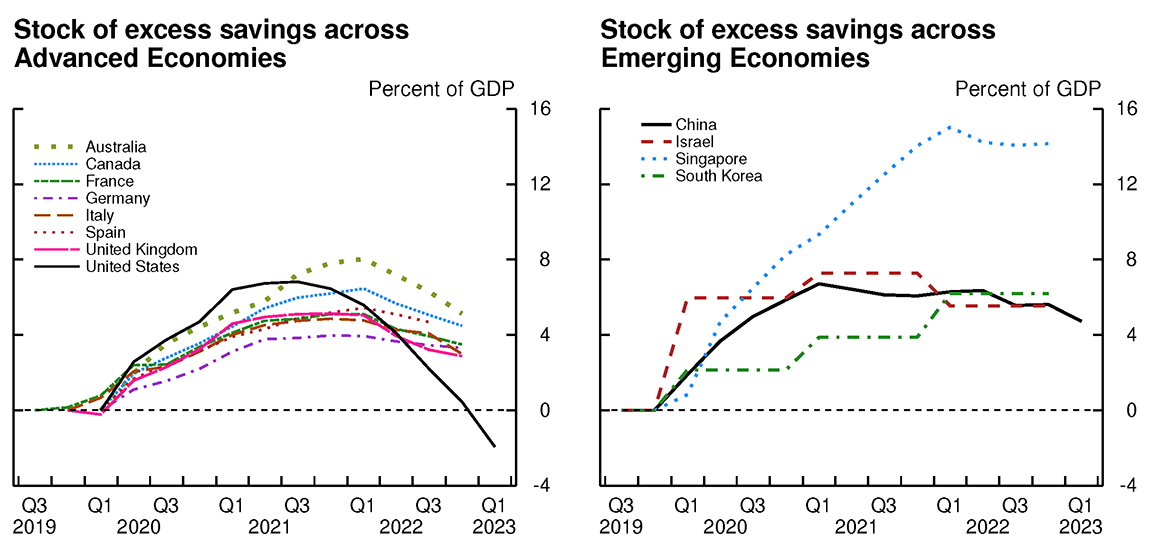

It’s also meaningful that household balance sheets in the US have already spent their stock of excess savings, meaning that they’re spending above their means. Surely, aggregate spending and hence GDP growth will have to come down.

Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) has an explicit policy of targeting 2% inflation. It’s not only controlling the short-term policy rate but also longer-term rates through the use of so-called yield curve control.

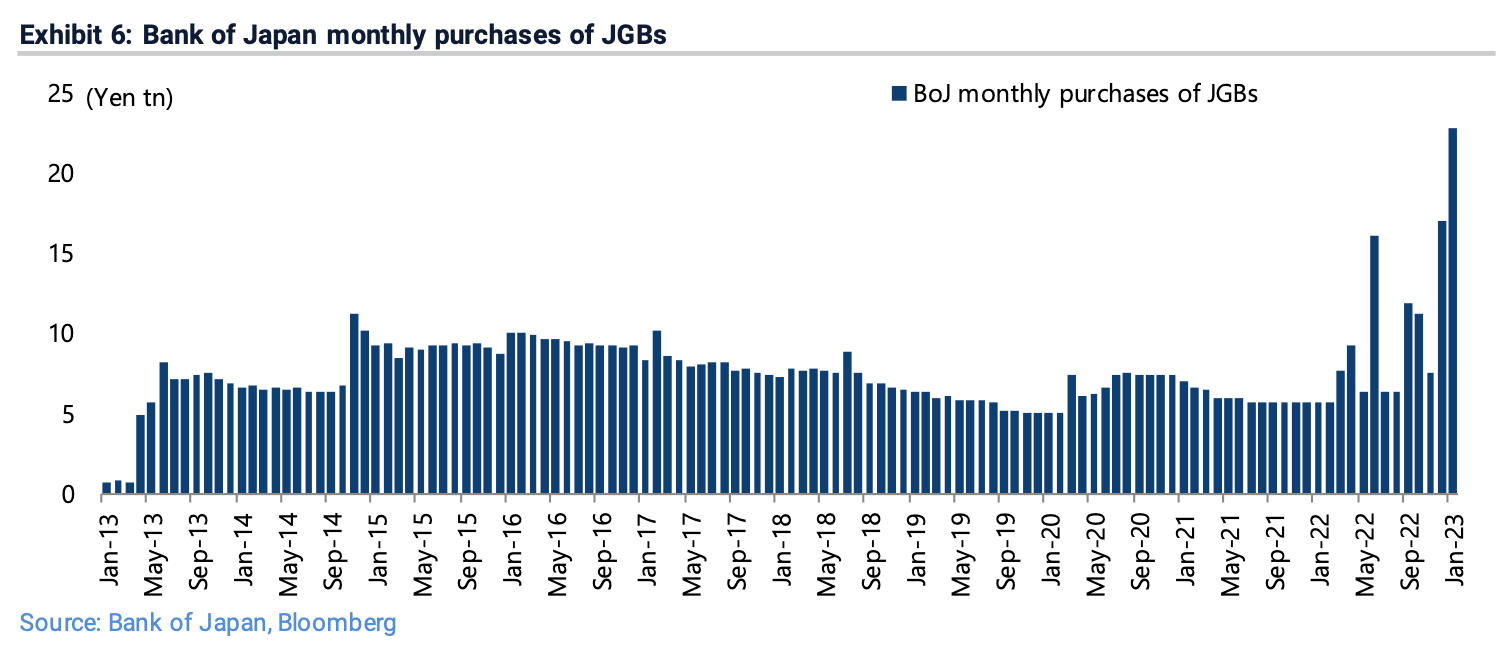

When US rates started rising in 2022, the BOJ engaged in large-scale quantitative easing to maintain Japanese interest rates where they were. The scale of these government bond purchases has been immense, as you can tell from the following chart:

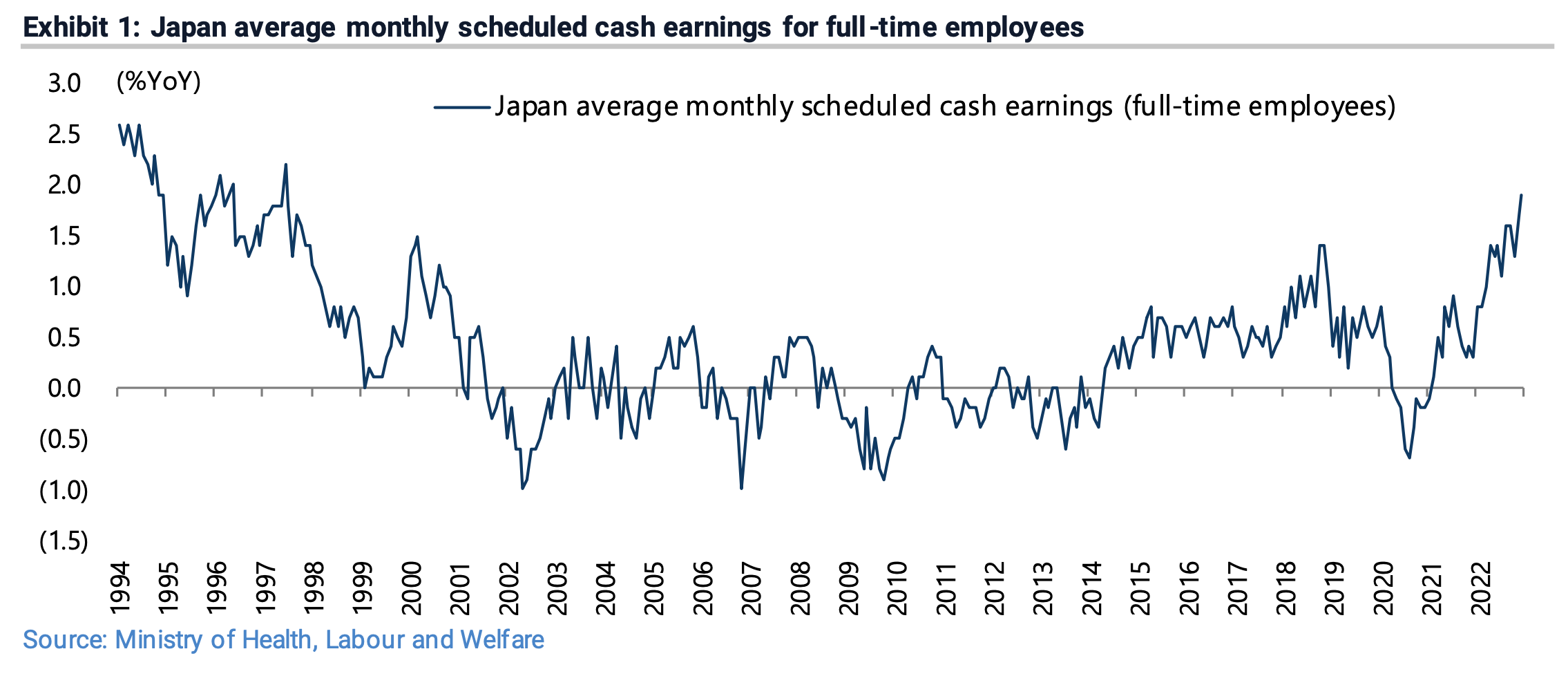

But we’ve now come to a point where it’s absurd to maintain the BoJ’s zero-interest rate policy. Japan’s wage growth is now the fastest since the mid-1990s.

Headline inflation hit 4% in late 2022 and remains above 3%. The BoJ Tankan Enterprises inflation expectations survey suggests about 2% longer-term inflation expectations - in line with BoJ’s target. And new BoJ governor Ueda has confirmed that the 2% inflation target will not change.

A shift in BoJ policy has become apparent in how 10-year bond yields were allowed to rise from 25bps to 50bps in late 2022. These are small steps, but the trend is clear.

So to summarise, while I’m certainly a macro tourist, it’s not inconceivable that the US-Japan interest rate differential will narrow at some point in the next 1-2 years. And it looks like the yen might appreciate against the dollar in such a scenario as carry trades are unwound.

2. Prior episodes of yen strengthening

Whenever we’ve had a global recession, the yen has strengthened. Japanese capital seeking safety after encountering losses overseas.

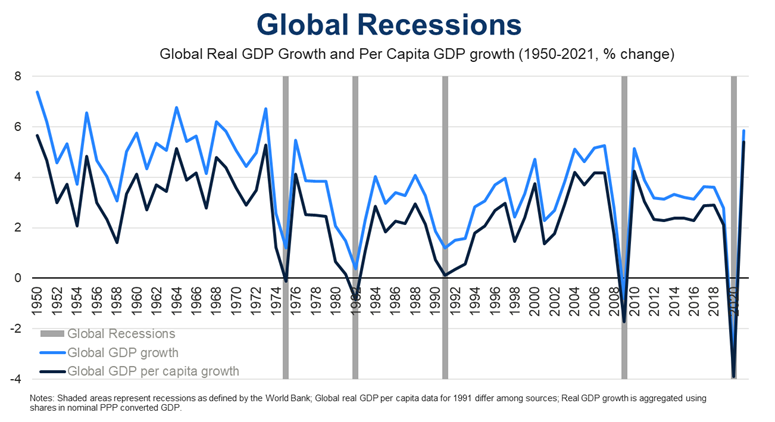

There’s been five instances of global recessions in the half-century: 1975, 1982, 1991, 2009 and the year 2020:

In the 1982 recession, the yen strengthened by around 20%, in 1991 by around 17%, towards 2009 by around 30% and in 2020 by just around 6%. Rough numbers, but I think you get the point.

I think this pattern will continue. The yen has traditionally been a funding currency for carry trades overseas, i.e. borrowing in yen to invest in higher-yielding assets overseas. Eventually, such carry trades reverse, and the yen returns to its prior level.

In his book The Art of Currency Trading, author Brent Donnelly recounts how such an episode of yen depreciation and appreciation can play out:

“The combination of low volatility and high carry in 2006 attracted huge pools of money to the long AUDJPY and NZDJPY carry trade and the strategy performed very well. Very well, that is, until the first tremors of the global crisis were felt and speculators decided all at once to unwind their carry trades as volatility roofed from abnormally low levels. This resulted in a colossal unwind of all carry trades and saw AUDJPY fall from 107 to 86 in about a month in the summer of 2007.”

Let’s now dig deeper to see what companies benefit from yen appreciation.

2.1. The Great Financial Crisis precedent

The Great Financial Crisis started with a credit crunch in 2007 and developed into a global recession by 2008.

The yen hit bottom on 22 June 2007 at 124 to the US Dollar and peaked on 17 December 2008 at 87, equivalent to a strengthening of around ~30%. Here is a chart of the USDJPY movements during this period:

Only 62 companies in Japan above a US$200 million market cap exhibited positive total returns during this period (price change plus dividends). Here is the list of the top names in this list: