Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

- The valuation disparity between Korean and Japanese equities has increased in recent years. This so-called “Korea discount” is due to conflicts of interest between controlling shareholders and minorities.

- Poor minority protection is the heart of the problem. High dividend and inheritance taxes have exacerbated it.

- Korea’s new Corporate Value Up program is a step in the right direction. However, since participation is voluntary, I don’t expect a wholesale shift in corporate governance.

- Individual companies might take some positive actions, including repurchasing discounted preference shares, selling cross-holdings, or canceling treasury shares.

- Towards the end of the article, I discuss 5 companies I’m paying attention to.

Three years ago, I expressed the view that the Korean stock market showed characteristics of a bubble. Since then, we’ve had a large decline and a stabilization in the main KOSPI index.

The key driver here is the consumer electronics boom we saw during COVID-19. But now, we’re starting to see a second driver of returns: corporate governance is slowly moving in the right direction.

In this post, I’ll discuss Korea’s ongoing corporate governance reforms and their implications for the Korean stock market.

Table of contents

1. The Korea Discount

2. Mechanisms for minority abuse

3. The Corporate Value Up program

4. The odds of success

5. Implications for investors

6. Conclusion1. The Korea Discount

The ”Korea Discount” refers to the fact that South Korean companies tend to trade at depressed valuations.

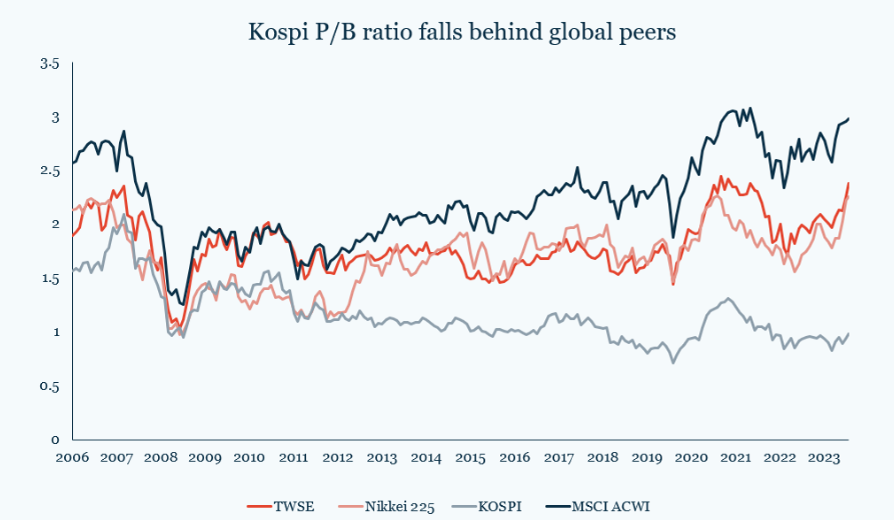

This discount has been around for decades, but it’s become even larger in the last few years. Today, South Korea’s benchmark KOSPI Index trades at just 1.0x book - way below Nikkei 225’s 2.1x book and the MSCI All Country World Index’s 3.0x book.

That Korean stocks are this cheap probably surprises many foreigners, who typically view Korea as a technology and manufacturing superpower. Samsung, Hyundai, and LG have become household names worldwide.

Even these highly successful companies trade at large discounts. Samsung Electronics - a world leader in memory chips, television sets and smartphones - trades at just 1.5x book and 12x forward P/E. Hyundai Motor trades at 0.7x book at 5x forward P/E.

On an index level, it gets even worse. Within Korea’s KOSPI index, almost two-thirds of the stocks trade below book value, compared to less than 40% in Japan and only 3% in the S&P 500.

The main culprit seems to be a low return on equity. That’s related to the fact that many of Korea’s industries are capital-intensive manufacturing businesses, along with poor capital allocation that hasn’t served the interests of minority shareholders.

Korea’s capital markets don’t function properly. 90% of the listed companies are controlled by families, and their control tends to be absolute.

In the early stages of South Korea’s development, the government openly supported its large conglomerates, known locally as chaebols. They frequently received support through bank loans, licenses and protection from foreign competition.

This support of family-owned businesses might have been fine when their highly entrepreneurial, original founders were still in charge. But today, many of Korea’s large corporations are controlled by second- or third-generation leaders who are frequently not well-equipped to run them. The focus is often on maintaining control rather than maximizing shareholder value. And as long as that remains the case, the Korean discount will probably remain.

2. Mechanisms for minority abuse

The main way that families remain in control is through convoluted corporate structures. A family might own 50% of a holding company, which in turn owns 50% in yet another holding company that owns the actual operating assets. Since the family controls each of the companies’ boards, they can also set the agenda for the operating company.

For example, in Samsung Electronics’ case, the Lee family continues to control it even though it only has 4.8% direct ownership:

![DECODED] Samsung, a giant in transition](https://www.asiancenturystocks.com/content/images/public/images/9116dee7-8566-44f7-bef4-36db84ae70d9_1200x900.jpg)

It achieves this through the control of Samsung C&T, Samsung Life, and Samsung Fire & Marine, all of which own additional shares in Samsung Electronics.

High inheritance taxes of 60% are part of the issue. After a patriarch dies, the next generation must find a way to sell down shares without losing control. That’s frequently when companies set up holding companies, and corporate structures start to become complex. Holding companies tend to own key intellectual property in the group, making it virtually impossible to separate them from the operating company.

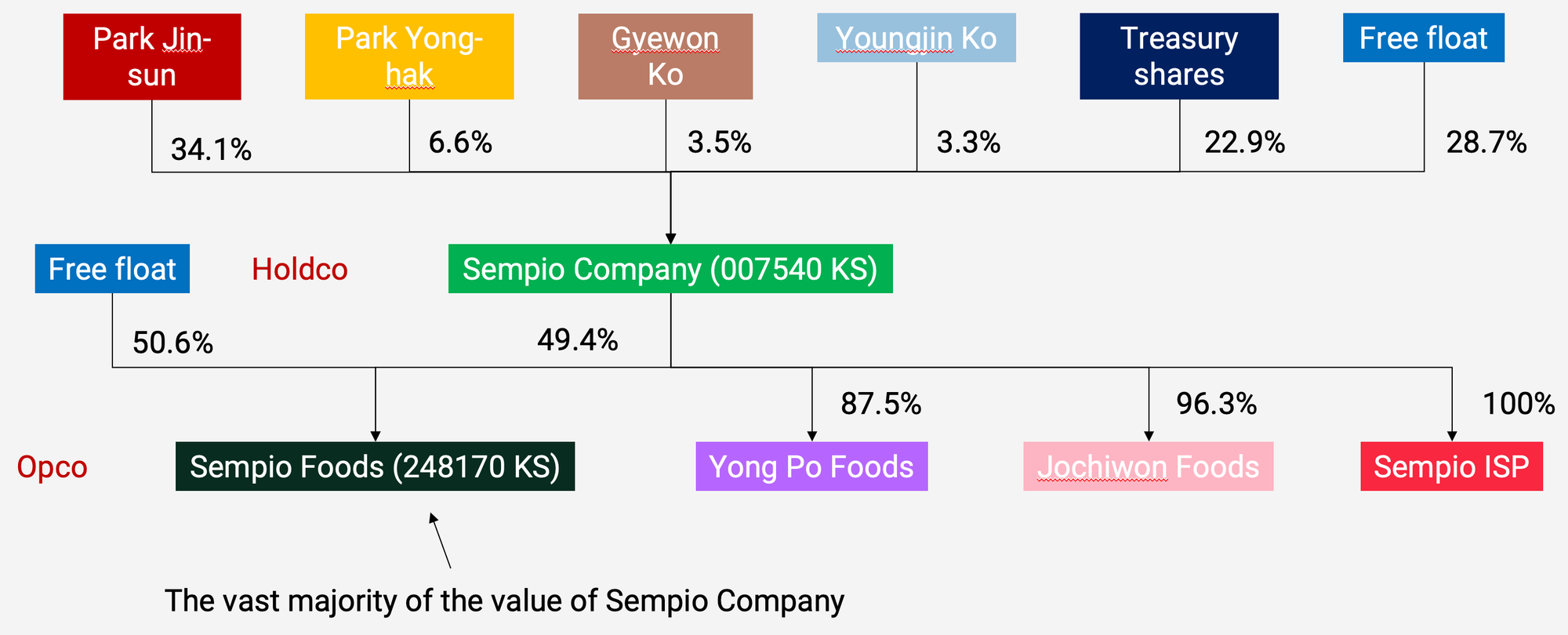

For example, take the case of Sempio Foods, a company I wrote about a few years ago. It’s one of Korea’s largest manufacturers of soy sauce. Sempio Company, with ticker 007540 KS, is the holding company in the group, and Sempio Foods, with ticker 248170 KS, is the operating company. Through this structure, the Park family can assert control over the operating company. Meanwhile, the key brand names are all owned by the holding company, giving it bargaining power against minority shareholders in the operating company.

The high inheritance taxes also provide incentives to keep stock prices low. The tax payment that the next generation is faced with is based on the total market value of shares owned. So, in this transition, families will try their best to keep aggregate market caps low to minimize inheritance taxes.

To achieve this, many families will keep dividend payments to a minimum. Corporate leaders often refer to dividends as “leakage”, revealing how they view minority shareholders: not as equals but as providers of cheap capital.

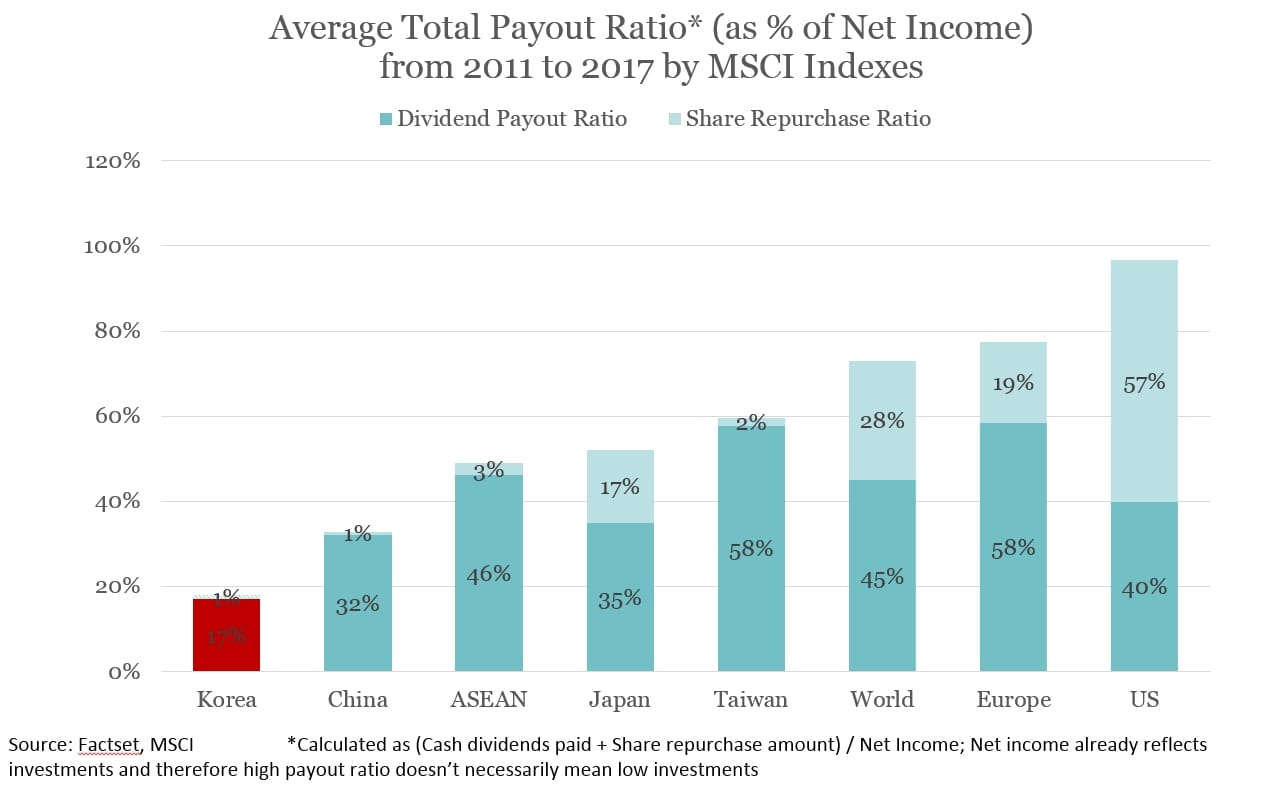

The following chart from Dalton Investments shows that Korea’s dividend payout ratio from 2011 to 2017 was just 17% vs 45% for the world as a whole:

South Korean tax laws also make dividend payments unattractive. Dividend income is included as part of overall income in tax assessments. In other words, dividend income is taxed at the top marginal tax rate of 49.5%, above a threshold of KRW 20 million per year (US$15,000).

So paying out dividends not only weakens the family’s ability to maintain control, it also leads to cash leakage to minority shareholders and unnecessarily high tax bills.

The other option for capital returns is share buybacks. And you do see share buybacks take place frequently. The problem is that acquired shares are rarely cancelled. Instead, they frequently stay on the balance sheet as treasury shares. Although such shares cannot be used as voting power, they are often sold to third parties on good terms with controlling families. It’s rare to find a company trading below book value that does not have a significant portion of its shares outstanding in un-cancelled treasury stock.

Another way to cement control is through the issuance of preference shares. In Korea, these are akin to non-voting common shares. As I wrote in the following article in 2022, they tend to trade at massive discounts to their common share counterparts, probably because they help raise capital for families without diluting their control.

So why do families care so much about control? Probably because money can funnelled out of listed companies without breaking any law. For example, unscrupulous individuals can make share prices go down on purpose and force minority shareholders to sell to them. Perhaps by merging a listed entity with a larger, more expensive and highly indebted related party. In Korea, minorities will find it difficult to prevent such underpriced takeovers.

Day-to-day related party transactions are also difficult to stop. They do not need minority shareholder approval, and they’re typically only disclosed after the fact in an annual filing. For example, if a holding company owns the group’s key brand names, then the pricing of royalties can easily move capital from one entity to another.

Certain shareholders activists have tried to deal with these problems. For example, in 2015, Paul Singer’s Elliott Management tried to stop the 2015 merger between two Samsung Group companies, Samsung C&T and Cheil Industries, which were underpriced and aimed to preserve the Lee family's influence. But Elliott failed to stop the transaction.

At the end of the day, it seems like controlling shareholders hold the upper hand. Anyone putting up a public fight can be sued for defamation, and in Korea, defamation includes any statement, even if it’s technically true.

My conclusion is that companies know exactly what needs to be done to close the “Korea discount.” They just don’t want to since doing so would be contrary to their own interests.

The government could certainly act, but the question is whether reducing tax rates is politically feasible. Korea’s conglomerates - the chaebols - are likely to put up a fight if and when greater protections are finally introduced.

3. The Corporate Value Up program

I’ve started paying attention to Korea’s corporate governance issue because Korea’s Financial Services Commission (FSC) has launched a reform program known as ”Corporate Value Up” or simply “Value Up.”

The program was announced in February 2024 and touted as a solution to closing the valuation gap between Korean equities and regional counterparts such as Taiwan and Japan.

The timing of the initiative has led many to conclude that Korea’s financial regulators have become envious of the success that the Tokyo Stock Exchange has had with its reform agenda and are now trying to copy its approach.

Given South Korea's and Japan's valuation disparities, closing this discount could lead to a massive upside.

The Value Up program will ask listed companies to submit plans on how they aim to enhance corporate value and shareholder returns. The purpose is to get them to pay higher dividends, reduce cross-holdings, and improve their capital allocation. These plans will be submitted early.

In late May 2024, the Korea Exchange introduced guidelines for the Value Up program on its Korea Investors' Network of Disclosure (KIND) website. According to these guidelines, companies are encouraged to provide yearly reports on how they plan to improve corporate values. In these reports, there will be disclosures of what each company plans to do to improve its corporate values and a set of financial indicators to track their progress. Some actions that will be encouraged include expanding R&D investment, reshuffling business portfolios, improving shareholder return via treasury stock cancellation and higher dividend payouts, selling underperforming assets and linking compensation schemes for executives to their corporate value-up plans.

In my mind, the key question is whether companies will be keen to participate in it. The program is voluntary, so what’s in it for them?

One of the key carrots is supposed to be tax incentives. The head of FSC, Lee Bok-hyun, has said that he wants the Value Up program to be included in the tax reform bill that will be presented to the National Assembly in July 2024.

Tax incentives could include lower inheritance taxes, a fixed dividend tax rate of, say 15.4%, or tax incentives for companies that prepare and communicate their Corporate Value Up plans. There could also be obligatory share cancellations after share buybacks and tax benefits for Individual Savings Accounts investing in Korean equities.

A key hurdle will be that the Korean public is seemingly obsessed with wealth redistribution, as highlighted in the Oscar-winning movie Parasite. Lowering taxes would be a stab in the back of voters, who typically hope for the rich to pay more rather than less.

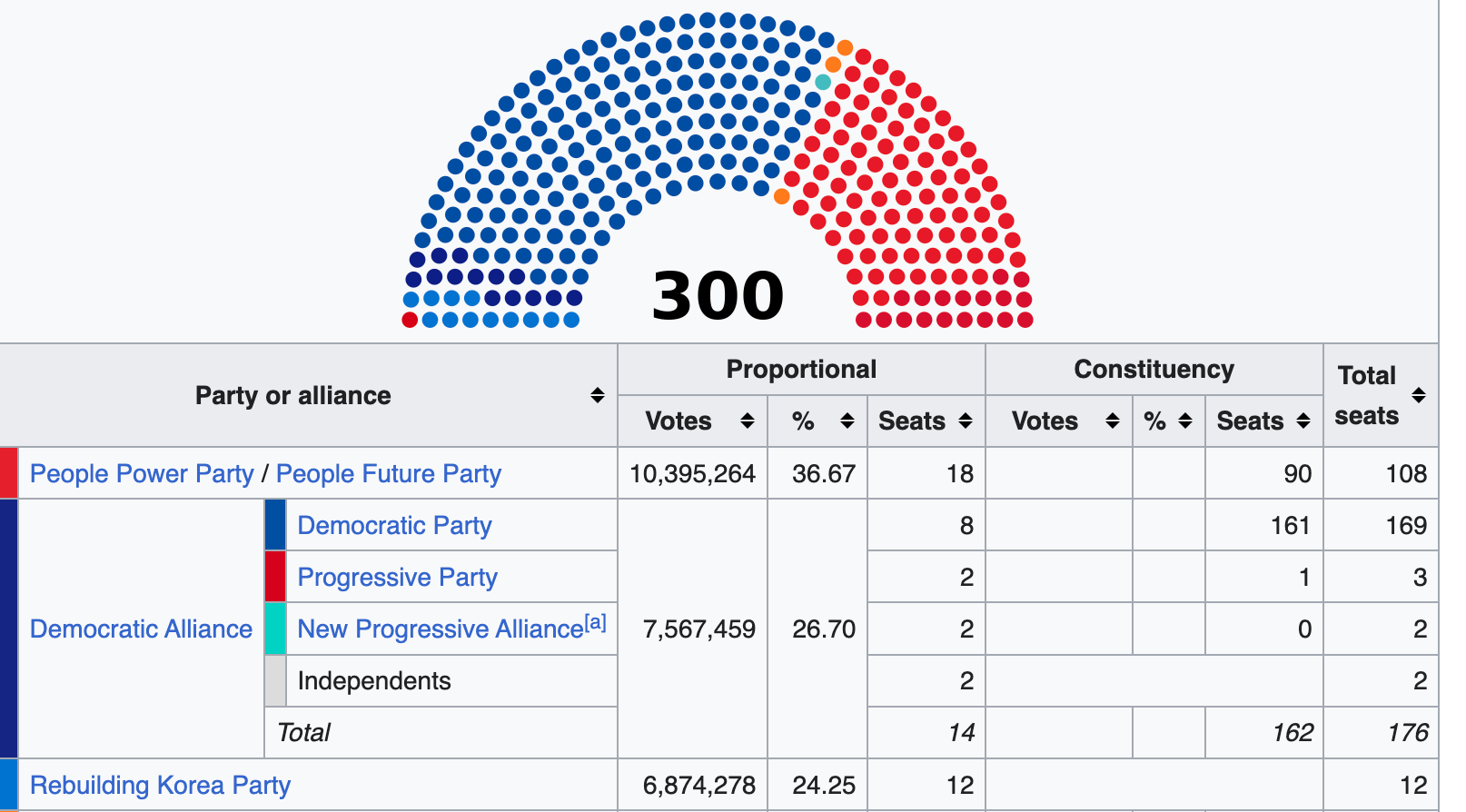

Another setback was the April 2024 legislative election, where the opposition won a landslide victory against President Yoon Suk-yeol’s People Power Party. Since the Corporate Value Up program is essentially his initiative, it is not clear whether he has parliamentary support for it.

So, while Yoon Suk-yeol is certainly pro-business, he has been unable to implement most of the deregulation policies that he has tried to push since becoming President in 2022.

There have been positive reforms on the margin. Yoon abolished the previous registration system for foreign investors. He’s also mandated English disclosures for listed companies and liberalized foreign exchange trading, enabling foreign brokerage firms to trade the Korean won.

These initiatives will improve foreign investors' access to Korean equities. Interactive Brokers apparently wants to offer its customers trading access to Korean equities.

But getting companies to improve their corporate governance will be a tougher nut to crack. The initial guidelines for the Corporate Value Up program were disappointing because they lacked concrete numbers on what the tax incentives were going to be.

Another carrot will be a new stock market index of companies that score best in corporate governance practices or show progress in their attempts to do so. This new “Korea Value-Up Index” is expected to be launched in September 2024. The National Pension Service of Korea and others will launch ETFs tracking the index in the fourth quarter of 2024. This should help allocate capital to companies that do better for their minority shareholders.

In any case, Vice Chairman of the Financial Services Commission Kim Soyoung has emphasized that this is only the beginning of the reforms, with more to come shortly.

4. The odds of success

This is not the first time that Korea’s financial regulators have tried to implement corporate governance reforms. For example:

- Under President Park Geun-hye from 2013 to 2017, the government tried to implement policies that improved shareholder returns. But after her impeachment, those plans were shelved. The public was largely against any reforms because tax reductions would disproportionately benefit the rich.

- Under President Moon Jae-in from 2017 to 2022, the government also tried to effect reform but had limited success due to strong opposition from Korea’s chaebols and the interruption from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Considering these failed reforms, it’s probably wise to be skeptical. At the heart of the issue is the fact that the families that control Korea’s chaebols have interests that diverge from those of minority shareholders.

For example, why would families want their companies to be part of an index that pushes up their share prices and thus leads to higher inheritance tax rates? And why would they willingly give up control of the companies they run?

Public pressure could lead specific companies to act, for example, by buying back discounted preference shares, selling non-core holdings, and cancelling treasury shares on their balance sheets. This would help on the margin.

But for a wholesale improvement in capital allocation, you’ll need much stronger financial incentives, including lowering inheritance and dividend taxes and making engaging in related party transactions more difficult.

There are success stories in the region. In Taiwan, individuals and corporations pay only a 10% withholding tax on dividends. Taiwan’s inheritance taxes are also low. Corporate governance is generally better, with higher dividend payout ratios and straightforward corporate structures.

However, public opposition to lower taxes means that revolutionary change is unlikely. Especially given that Yoon Suk-yeol’s People Power Party does not hold a majority in the National Assembly. And opposition from chaebols means that an improvement in minority protections is unlikely.

Another question mark is that Lee Bok-hyun, who spearheaded the Value Up initiative at the Financial Services Commission, is likely to leave and move to the presidential office. There is top-down support for the program, but it’s unclear whether it’ll be enough.

5. Implications for investors

The benchmark KOSPI index has performed nicely this year on expectations that the Value Up reforms will unlock value. Over US$10 billion has been spent on net foreign buying of Korean equities, with low-price/book stocks rising the most.

Korea is a retail-driven market, and many are now bidding up the share prices of banks, insurance companies, brokerage firms, carmakers, and capital goods companies. Some chaebols have started to cancel treasury shares, and banks have raised dividend payouts.