Table of Contents

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

- The book Spy the Lie describes tactics you can use to determine whether someone is lying.

- Identifying deception involves asking a question and then looking and listening for reactions to that question.

- These reactions can be verbal, such as failures to answer the question, failing to deny an allegation, attacking the person asking the question, inappropriate reactions, using qualifiers and efforts to influence your views on them.

- Reactions can also be non-verbal, such as delays in answering, grooming behaviors, face movements or shifts in a person’s anchor points, or a disconnect between body language and what the person is saying.

- If you find clusters of verbal or non-verbal red flags, you’re gaining confidence that the other person is probably telling a lie. The next step will be to dig deeper and perhaps even get a confession from the person.

A few weeks ago, a short-seller friend recommended me a book called Spy the Lie.

The book describes techniques to tell whether someone is lying or not. It was written by a former CIA interrogator who conducted thousands of meetings with suspects that might endanger US national security.

I think the book can also be helpful for investors, too. Understanding whether a management team is being truthful can help you gain conviction that the numbers are real and as positive as they say they are.

Table of contents

1. The Model

2. Questions to ask

3. Verbal behaviors

4. Non-verbal behaviors

5. Unreliable signals

6. Deception in practice

7. Conclusion1. The Model

The book Spy the Lie was written by three former CIA officers. The main author, Philip (“Phil”) Houston, specialized in polygraph tests, sitting down with people under investigation to assess whether they were lying or not.

A polygraph test is a lie detector, measuring a person’s pulse, perspiration or breathing pace after being asked a question. If they experience a fight-or-flight response, it will show up in the measurements.

But it’s possible to detect cues of lying even without using a polygraph. In the book, Phil and his co-authors describe verbal cues, such as evading the question, and non-verbal ones, like touching your face.

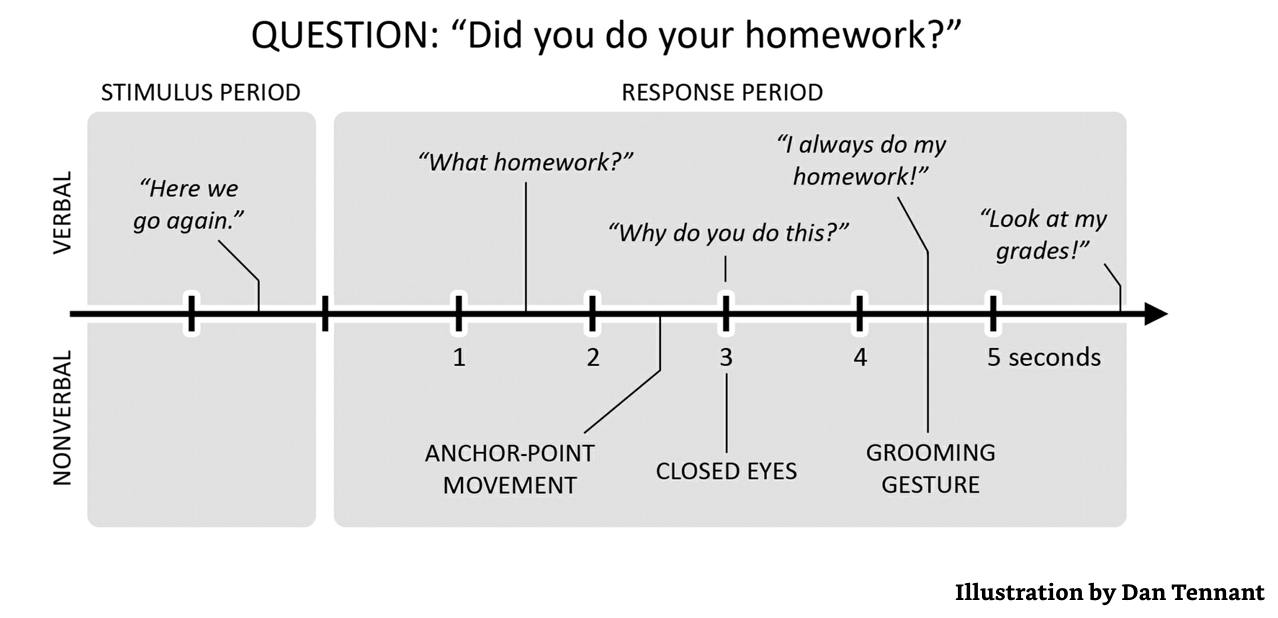

The assessment begins with a question and then waiting for cues that might either signal truthfulness or deception:

This process from start to finish is what’s referred to in the book as The Model:

- First, ask a question like “Did you do your homework?” This serves as a stimulus for potential reactions from the subject.

- In the first five seconds after delivering the stimulus, look and listen for clusters of deceptive behaviors. These could include pretending not to understand the question (“What homework?”), moving to a different sitting position, closing eyes, etc. The greater the number of deceptive behaviors, the greater our confidence that the person is indeed lying.

The Model doesn’t provide clear answers, though. You can never be 100% sure that someone is lying without actual evidence.

But if the deceptive behaviors add up, you’ve identified a potential problem area, and you’ll need to dig deeper. Handled correctly, you might even get a confession out of the subject.

The model should be applied rigorously. Only pay attention to deceptive behaviors occurring right after stimuli. You should ignore other truthful statements as they cause us to form biased views of the person. Discipline is needed.

2. Questions to ask

Before a question, you can start with a prologue statement that provides legitimacy and rationalization for the coming question. This can also help minimize the issue in the subject's eyes and make the person more cooperative.

For example, here is a prologue statement used before a question to increase the chances that a person will admit to having used drugs:

“The next thing I need to ask you about is drug use. Now, before we get into that, let me explain why it’s important that we ask this question, and what we’re looking for. First of all, we know that a lot of folks have tried things. That’s not a particular concern to us. What we are worried about is if someone has a significant drug problem.”

The question should be aimed at discovering the truth about a particular matter. Phil and his colleagues suggest that a question should fulfil the following criteria:

- Short: to provide less time for the other person to think through an alibi

- Simple: the person has to understand your question; otherwise, any reactions to it won’t contain any signal

- Singular: keep to one question only; otherwise, the person will avoid answering the one that could be incriminating to him

- Straightforward: the more upfront you are, the more likely the other person is going to trust you, increasing the likelihood of cooperation

Questions can be open-ended (“What drugs have you taken?”) or closed-ended (“Have you ever smoked marijuana - Yes/No?”). Open-ended questions are best in the beginning to set a foundation for a future discussion. And closed-ended questions are best towards the end to get to the actual truth.

To get the answers you’re looking for, you’ll want to ask questions the accused is unlikely to have prepared for. One trick is to ask presumptive questions, which presume some wrongdoing.

For example, murder suspect OJ Simpson was asked, “What happened at Nicole’s last night?” - presuming that he was indeed at victim Nicole’s house. The only correct answer in this instance would have been “I wasn’t there”. Anything else could be a red flag.

You can end the questioning by asking follow-up questions like “What else?” or “Tell me more”. To uncover lies of omission, ask them: “What haven’t I asked you that you think I should know about?”

Once you detect a lie, you don’t necessarily have to dig into the issue. You can also broaden your focus by asking more general questions to get a fuller picture.

Using the drug example above, for instance, if a subject admits to having smoked marijuana, you can ask him what other drugs he or she has tried. That will be perceived as less confrontational, more conversational - as if you’re two good buddies, just chatting back and forth.

Negative questions should absolutely be avoided. They’re leading questions that give the person a way out. For example, if you ask, “You’ve never smoked marijuana, have you?” the temptation will be too great to just say “No.”

Finally, avoid complex and vague questions. If your questions aren’t clear, you won’t get any clear answers either.

3. Verbal behaviors

Now that you’ve asked a question, the next step will be to spot deceptive behaviors within the first 5 seconds.

People will rarely lie straight to your face (“lies of commission”). They’ll go to great lengths to avoid it. Instead, they’ll most often leave out a part of the truth to deceive you (“lies of omission”). Or try to influence your perceptions of them (“lies of influence”) so as to minimize the crime.

The first deceptive behavior you should pay attention to is failure to answer. If people don’t answer your questions, it’s usually because they don’t want to lie to your face. However, be careful - there is a risk that they simply didn’t understand your question.

For example, check out the following video, where a Shark Tank contestant is asked whether he can give a discount (from 6:26 to 7:40). He refuses to answer the question, which suggests he cannot provide a discount.

Later on in the same video, a mother is asked where her missing child might be (from 7:40 to 9:00). In both of these cases, a failure to answer signals deceptive behavior:

Another type of deceptive behavior is denial problems, such as failing to deny a serious allegation.

For example, if a man is accused of cheating on his spouse, instead of saying “I didn’t do it”, he might say something along the lines of “I would never do something like that” - a non-specific denial that allows him to avoid lying straight to your face.

Alternatively, instead of denying the allegation, subjects might provide a long-winded answer in an attempt to create confusion and cover up a lie.

If the subject repeats the question asked, that might be a sign of trying to buy time while thinking of an alibi. Repeating a question can also be a way to fill in an awkward moment of silence. They’re afraid they might be caught lying.

A similar tactic is to provide a non-answer statement. For example, people might buy time by saying, “That’s a good question” or “I’m glad you asked that,” while thinking through an alibi.

If a person provides inconsistent statements, at least one of the statements must be false.

For example, have a look at the following interview. Former senate candidate Christine O’Donnell was asked whether she supported “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” policies. She replies that she’s not talking about policies, but also that she’s promoting policies that are “mostly fiscal, mostly constitutional”, two statements that are inconsistent with each other:

When people go into attack mode, that’s a sign that they have something to hide. They might attack your credibility or competence and try to get you to back off.

Another problematic behavior is when people reply with inappropriate questions rather than answering the question asked.

In the book, Phil tells the story of when he accused a man of stealing a computer. Instead of denying it, the man replied “How much did it cost?”. This question had nothing to do with the theft. Instead, it reflected a concern that he might be facing felony charges.

Sometimes, the person accused of something provides answers that are overly specific. For example, if you ask a CEO how the last quarter was, and he replies by saying that a small division of his company did well - that’s a red flag. He’s clearly trying to shift attention away from the fact that the last quarter wasn’t as strong as he would have liked.

Another example: in the following interview, former US President Bill Clinton is asked whether he had a twelve-year affair with a woman. He stutters and then replies that “the allegation is false”. He provided a specific answer to a specific question, and his answer was technically true since his affair only lasted for 11.5 years:

Sometimes, subjects might exhibit inappropriate levels of politeness to make the other person like him or her. If we like them, we’re more likely to believe in what they’re saying.

People who are accused of something might also try to diminish the importance of the issue. They might say, “Why is everybody worried about this?” and perhaps even joke about it. It’s a way to lower their anxiety and guilt. In the book, this tactic is referred to as an inappropriate level of concern, i.e. they’re not being concerned enough.

For example, in this clip, Scott Peterson laughs when asked whether he murdered his wife. Clearly, he exhibited an inappropriate level of concern.

Another sign of deception is a process or procedural complaint. For example, asking “How long is this going to take?” or “Why are you asking me this?”. Such complaints are simply a way to buy time and deflect the question.

Sometimes, a deceptive person will refer to previous statements, for example, by saying, “I would refer you to my earlier statement…” or “As I told you before…” These referral statements are ways to build credibility and deflect the question.

People who are accused of something might also invoke religion to dress up the lie. They might say, “I swear to God” or “God knows I’m telling the truth.” in an attempt to gain credibility and make it seem like they’re telling the truth.

Another type of deception is to display selective memory. If people say that they don’t remember, then that provides them with an alibi - we can’t force somebody to remember. They might say “Not that I recall”, “To the best of my knowledge”, “Not that I’m aware of” and “As far as I know”.

Here’s an example of a man not remembering a particular text message he sent:

If a person uses qualifiers such as “not really”, “basically”, “probably”, “usually”, “for the most part”, etc, it’s a sign that they’re withholding information about the specific circumstances of the case to avoid lying. Other qualifiers such as “frankly”, “truthfully”, “to tell you the truth”, etc. are used to enhance credibility.

Finally, a person accused of something might resort to convincing statements to get others to believe he or she is an upstanding individual. For example, the person might say:

“I would never do anything like that”

“Why would I risk my life for a few measly dollars?”

“I have a great reputation”

“It’s not in my nature to do something like that.”

“I always try to do the right thing.”

“I love you, I would never do anything to hurt you”.

Such statements appear convincing, but they’re intended to mislead and do not answer the actual question being asked.

If you’re faced with convincing statements from the subject, the best way to deal with them is to agree and repeat them. And then go back to the original question by saying something along these lines:

“Yes, I know you love your kids. I think that’s evident to everybody. But, we want to talk to you now about what really happened. We want to go over your story again”.

Even though they’re trying to convince you they’re upstanding individuals, you don’t want to let them off the hook.

4. Non-verbal behaviors

The majority of communication is non-verbal, i.e., it occurs through your body language. And there are certain non-verbal behaviors that tend to be associated with deception. Let’s go through them one by one.

First, if there’s a noticeable delay in an answer to a simple question, there might be a problem. If you ask a person: “Seven years ago, did you rob a gas station?” and there is a 5-second delay to the answer, there’s a problem here. The answer should come immediately, preferably along the lines of “No!”

If there’s a disconnect between verbal and non-verbal behaviors, then that might indicate a problem. For example, if a person nods his or her head sideways while saying “Yes”, that could be an issue, at least not outside of India.

If people want to cover up their tracks, they might unconsciously hide their mouths or eyes. They might pull up their hand to their mouth and cover it. Or simply close their eyes.

Clearing the throat or swallowing before answering a question might be a symptom of anxiety. That anxiety exhibits itself through discomfort or dryness in the mouth, part of the fight-or-flight instinct.

If subjects respond with facial movements, that’s another sign of anxiety. They might put a hand to their face, bite their lips or pull their ears. What’s happening physiologically is that the body is rerouting circulation to vital organs. The diminished blood supply to the face causes irritation in the capillaries, and they will consequently want to scratch their faces.

Anxiety also causes people to move their bodies, especially the anchor points which anchor the body to the floor. Examples of so-called anchor points include feet if a person stands up or buttocks if sitting down. For this reason, it’s best if interviews take place in chairs that have wheels and can move around to amplify any behaviours that occur in response to your questions.

Grooming gestures are also used to dissipate anxiety. Subjects might adjust their ties, shirt cuffs or glasses, straighten their shirts or move the hair behind their ears.

Here are some examples of unconscious behaviors that reflect building anxiety. In this example, we see a man putting his hand to his face, exhibiting grooming gestures as well as shifts in his anchor point:

5. Unreliable signals

There are also several behaviors that are unreliable when it comes to judging whether someone is lying or not. So, be careful when drawing any conclusions from them:

- Failing to make eye contact is commonly seen as a sign of deception. But there could be many reasons why a person doesn’t want to maintain eye contact, including shyness.

- A closed posture is another potentially false signal. The person might simply be cold or reflect a closed personality type. Similarly, clenched hands could be a signal of anxiety but also a sign that the person is afraid of authority figures.

- Nervous tension could also be due to many other factors, including medication. The person might be neurotic. The same is true of blushing or twitching.

- Some people think that it’s possible to observe the baseline of a particular person’s behavior and then watch out for deviations from that baseline. For example, if people belong to a certain group, then judge them based on their affinity to that group. The problem with that method is that our behaviors are incredibly complex, and you can’t attribute all deviations to deception.

So to summarize, it’s better to stick to more rigorous models, focusing on behaviors that have been proven to be associated with lying. Like the verbal and non-verbal behaviors described above.

6. Deception in practice

The book ends with an analysis of an interview with Congressman Anthony Weiner when he was accused of sending sexual text messages to female college students despite being of age and in a committed relationship with children. These Twitter messages came out to the public. Anthony Weiner claimed his account was being hacked and promised to prosecute whoever was responsible for the hacking.

Have a look at the following video and see if you can detect any deceptive behavior on the part of Anthony Weiner:

In answer to the first question at 0:08, Anthony Weiner fails to answer the question, uses qualifiers such as “I think” and “pretty”, downplays the issue by calling it a prank and uses referral statements to gain credibility and try to get out of the questioning.

In his answer to the second question at 0:36 about why he’s not asking law enforcement to investigate the supposed hacking of his accounts, Weiner touches his nose with his hand and then fails to answer the question again, instead downplaying the issue with an unrelated rhetorical question that seems intended to mislead.

In response to the third question at 0:52, Weiner attacks the interviewer by saying, “Do you want to do the briefing?” and then uses an inappropriate level of politeness by saying, “Sir,” again, not answering the question.

In response to a later question at 1:50, Weiner fails to answer another question, uses referral statements to gain credibility and again attacks the interviewer by saying “Why don’t you let me do the answers and you do the questions”, which doesn’t make any sense since they are asking questions. He’s getting frustrated at this point.

In the follow-up question at 2:17, he ridicules the question, shows an inappropriate level of concern for what is a serious allegation, and again fails to answer the question asked.

In answer to the question at 2:57, Weiner claims that there is a tactic of someone out there who’s out to get him framed, making a convincing statement that he’s the victim, even though he’s the person who made the statement that his Twitter account was being hacked. Again, he fails to answer the question asked.

Later on, in a question about why Weiner hasn’t asked the police to investigate the hacking, at 4:00 Weiner uses the “frankly” qualifier to gain credibility. He also provides another convincing statement: that all he’s trying to do is serve his constituents and the country. Fair enough, but he’s just trying to gain credibility and still not answering the question asked.

To summarize, Anthony Weiner was lying through his teeth. He avoided answering the questions asked, tried to change the subject, showed signs of being anxious, tried to downplay the issue by joking around, then attacked the interviewer and used qualifiers and convincing statements to seem like a decent person. But he was guilty of the accusations, and his evasive behavior gave it away.

7. Conclusion

Identifying deception involves asking a question and then looking and listening for reactions to that question.

- These can be verbal, such as failing to answer the question, failing to deny an allegation, attacking the person asking the question, inappropriate reactions, use of qualifiers, and efforts to influence your views on them.

- Non-verbal reactions include delays in answering, grooming behaviors, face movements or shifts in a person’s anchor points, or a disconnect between body language and what the person is saying.

You’ll need to find a cluster of red flags — at least two are necessary to determine that the person is lying. Now that you’ve identified a lie, the next step is to dig deeper to get closer to the truth.

I hope this post was helpful to you. If you’re interested in reading the entire book, you can find it on Amazon here. I highly recommend it.

Thank you for reading 🙏

If you would like to receive 20x high-quality deep-dives per year and other thematic reports, subscribe to Asian Century Stocks - all for the price of a few weekly cappuccinos.