Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Japan has been in a bear market for many years. But now, the twin locomotives of a weak currency and structural reform are finally pushing the Nikkei higher.

In this post, I’ll discuss the structural reform part of the equation: how Japan’s corporate governance reforms unlock value from those overcapitalized balance sheets, and discuss the companies leading the way.

Table of contents

1. Keiretsu capitalism

2. Abenomics

3. The Prime Market

4. Naming & shaming

5. Early signs of success

6. Potential beneficiaries

7. Conclusion1. Keiretsu capitalism

During Japan’s early industrialization phase, you saw the rise of Japanese conglomerates, including Mitsui and Mitsubishi. These became known as zaibatus - family-controlled groups of companies that dominated entire industries.

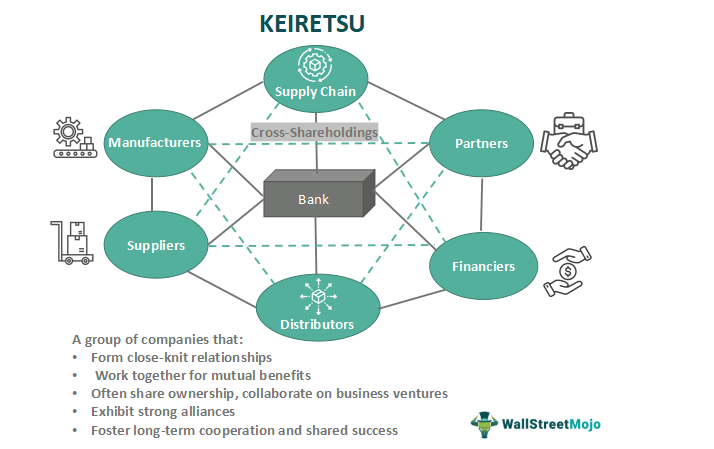

But due to their association with the Japanese war apparatus during the Second World War, they were eventually dismantled. In their place, a new commerce system arose, with companies forming around Japan’s largest banks. These new groups of companies became known as keiretsus - groups of companies surrounding a particular bank.

In keiretsus, banks provided businesses with loans and transferred their employees to important positions in the firms they lent to. And within each keiretsu, companies would buy shares of the others in the group. The environment became predictably clubby. Don’t believe me? Read this article about the keiretsu formed around Mitsubishi UFJ Bank in Kyoto. And it’s just one of many.

These arrangements pushed companies to grow at all costs, favoring management, clients, suppliers and the banks - practically everybody except minority shareholders.

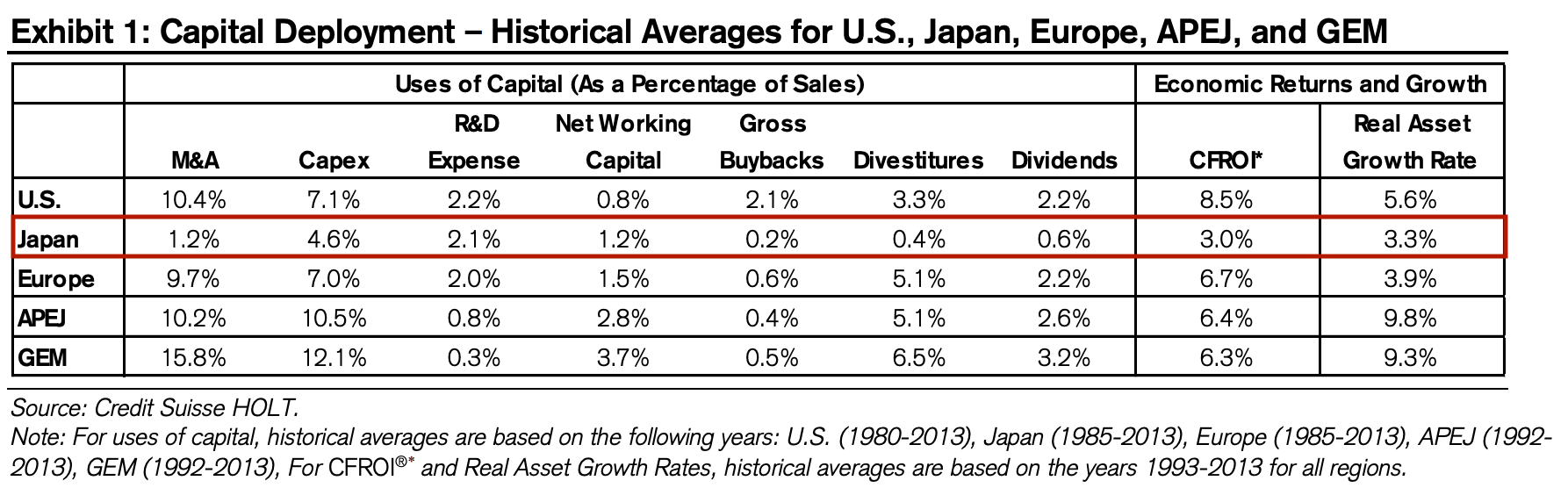

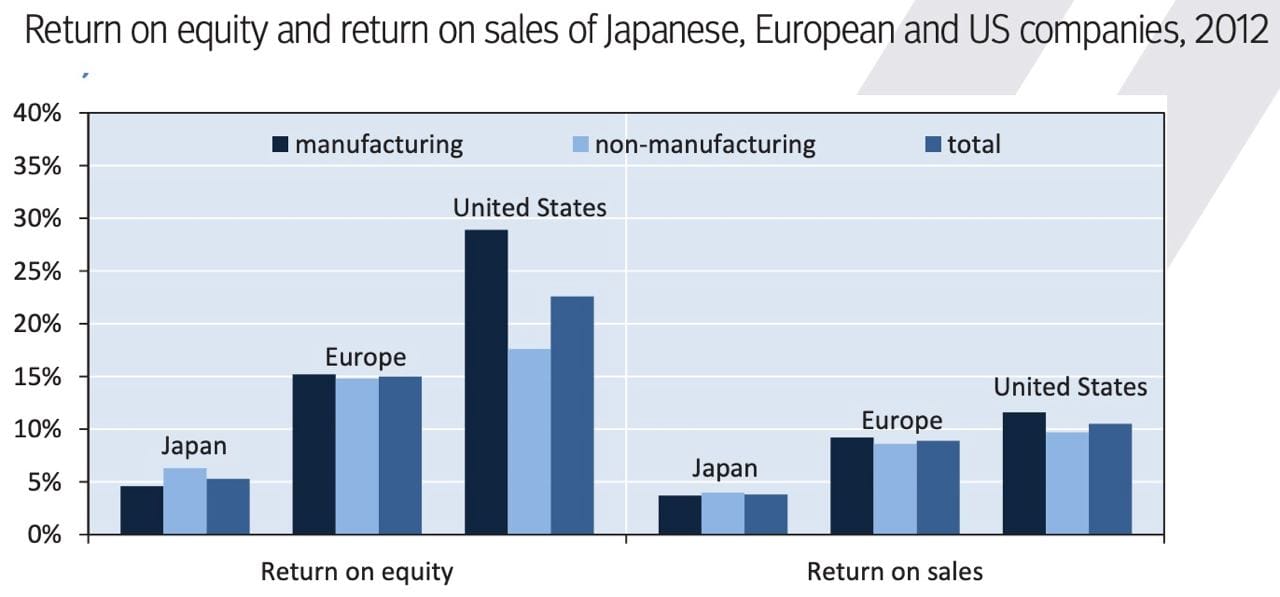

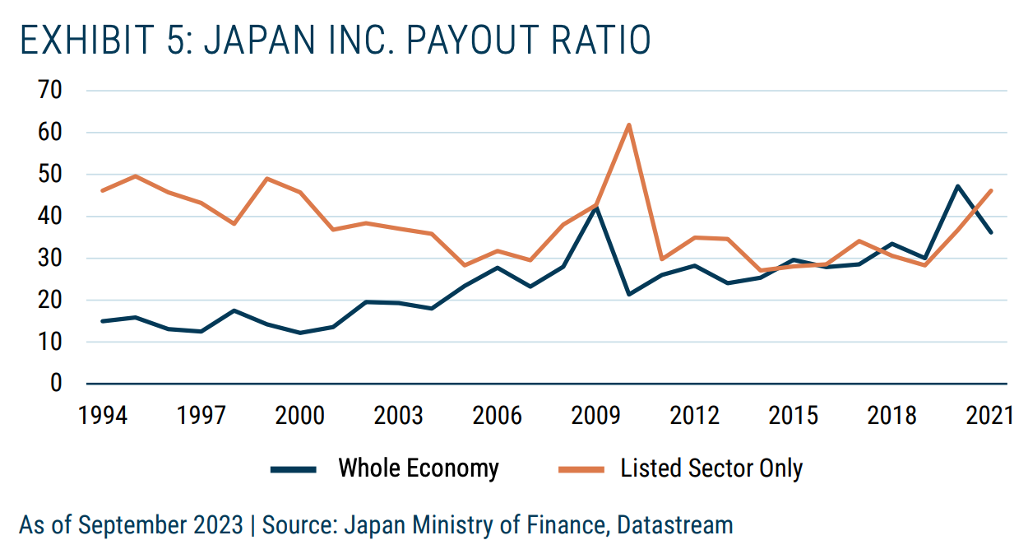

The result was poor capital allocation across Japan’s corporate sector. According to numbers from Michael Mauboussin, from 1980 to 2013, Japan’s capital allocation was among the worst of any major region in the world. It was characterized by low returns on capital, low dividend pay-out ratios, few share buybacks, and practically no market for corporate control.

The following chart from the OECD drives home the point that Japanese companies have been underperforming. Bloated balance sheets, an accumulation of cash and unnecessary cross-shareholdings caused their returns on capital to lag those in Europe and the United States:

2. Abenomics

The first signs of real change came with the election of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. In 2013, he introduced a new economic plan, which came to be known as “Abenomics”.

This reform plan rested on “three arrows” aiming to revive Japan’s stagnating economy: 1) aggressive monetary policy, 2) flexible fiscal policy and 3) structural reform.

The structural reform agenda was broad, including deregulation, labor market reform, free trade agreement and greater R&D. He also oversaw the introduction of two new documents that are now seen as having kicked off Japan’s corporate governance reform:

- The Stewardship Code in 2014 required fund managers to put clients’ interests first when voting in board meetings. For example, soon after it was introduced, voting proxy services firm ISS announced that it would recommend voting against the management of any company with a return on equity below 5%. This put real pressure on management teams to perform.

- The Corporate Governance Code in 2015 reformed listing rules and emphasized long-term value creation and ESG factors. This law was inspired by the UK’s shareholder-friendly corporate governance code. It discusses how the board is responsible for improving capital allocation and not just letting cash accumulate on the balance sheet. And it pushed for independent directors.

Since 2015, we’ve seen some improvement in the capital allocation of Japanese companies. For example, the dividend payout ratio has risen further:

There were also other signs of positive change. The number of poison pills - a takeover defense mechanism meant to entrench corrupt management teams - fell drastically. We saw the emergence of shareholder activism, with the number of shareholder proposals by activists rising almost five-fold. And it’s become the norm to have at least 1/3 independent directors on company boards.

3. The Prime Market

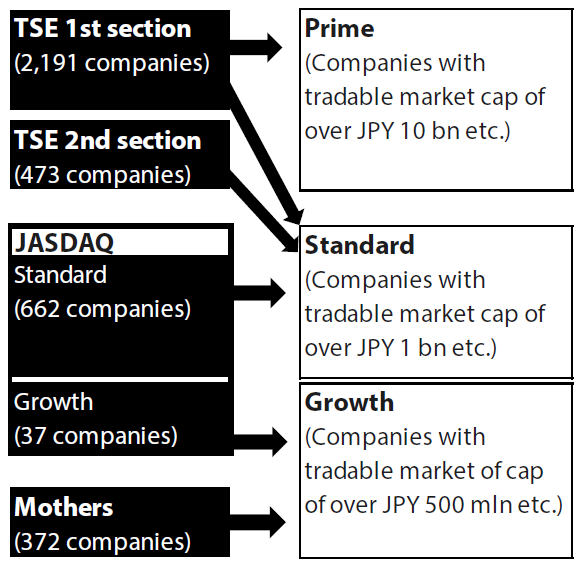

The next phase in Japan’s corporate governance reforms came in 2021 when the Tokyo Stock Exchange announced a new listing structure.

From now onwards, listed companies would move from the previous categories “1st section”, “2nd section”, “JASDAQ”, and “Mothers section” into the following three:

- Prime: High market cap and liquidity and strong corporate governance

- Standard: Market cap and liquidity above a certain level

- Growth: For companies with business plans to achieve high growth

It wasn’t just a change in the names of the sub-markets of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Japan’s listed companies would need to meet certain standards to qualify for a Prime Market listing.

To become a member of the Prime Market, they had to meet certain criteria such as a minimum market cap of tradable shares (>JPY 10 billion), a minimum tradable share ratio of 35%, divesting their cross-holdings and communicating with foreign investors in English.

For the Standard Market, the requirements were now having free-floating shares worth JPY 1 billion, a free-float ratio above 25%, ensuring that at least 2/3 of directors were independent and disclosures in English.

If companies don’t meet the criteria by 2025, they’ll be “designated for supervision” and given a 1-year grace period to get back on track. If they still don't meet the criteria at the end of this year, they’ll face a potential delisting.

An important detail in the 2021 document is that the exchange quietly shifted the definition of “tradable shares”. Since then, tradable shares no longer included shares owned by Japanese commercial banks, insurance companies or corporations.

This definition might seem minor, but it’s important: if companies face greater pressure to increase the market cap of tradable shares, they’ll be forced to reduce cross-shareholdings. Japan’s keiretsu arrangements are being further weakened. And minority shareholders are seeing their bargaining power improve.

4. Naming & shaming

The latest stage of Japan’s corporate governance reform might prove the most effective.

In early 2023, a Tokyo Stock Exchange document requested companies trading below book value to come up with. capital improvement plans - to devise a strategy conscious of their cost of capital and share prices.

This was a radical shift because now, companies will also have to take the market value of their shares into account when allocating capital.

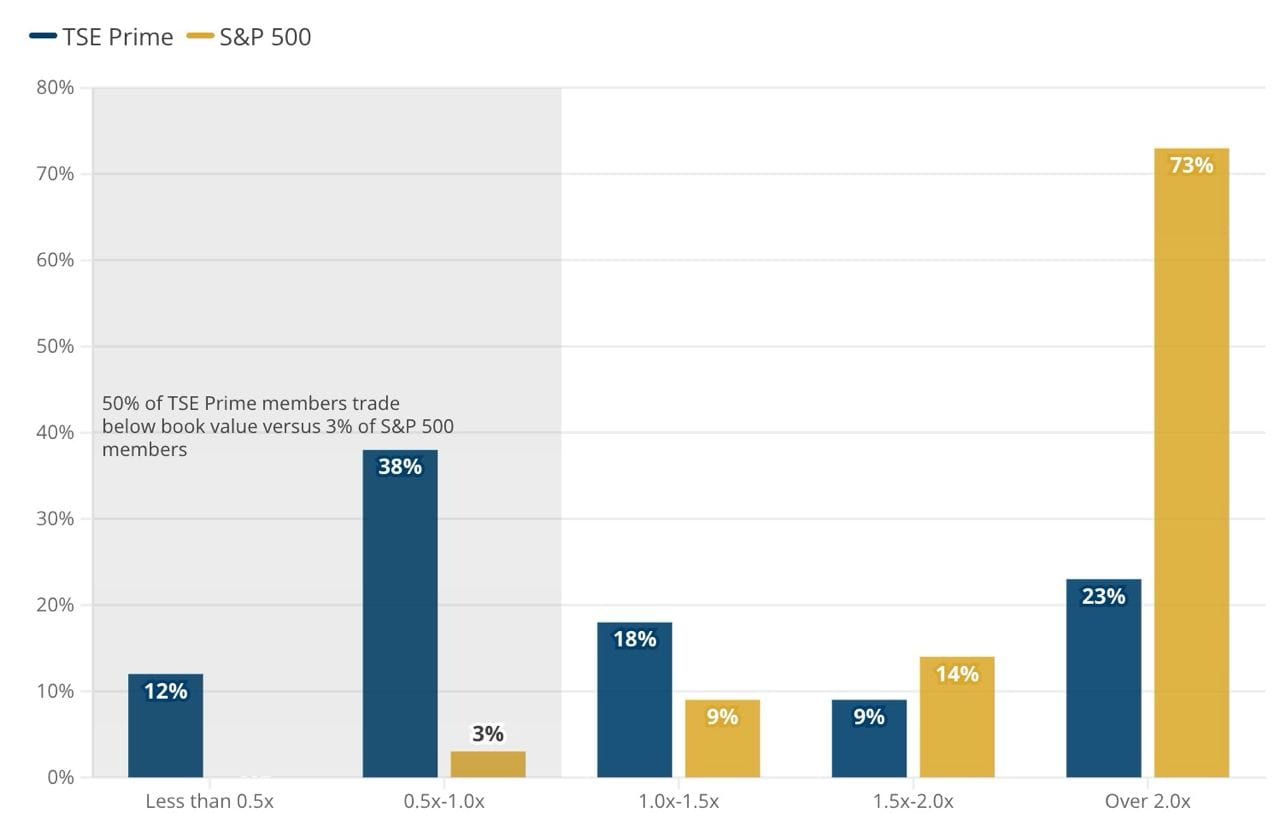

Roughly 50% of Japan’s TOPIX constituents have a price/book ratio below 1x. And 65% of the Russell Nomura Total Value Index trade below book. Just imagine what would happen to Japan’s stock market if the number of below-1x price/book stocks fell to the US level of 3%.

An 8% return on equity is the magic number to achieve this valuation. And so, the exchange is now pushing companies to consider this metric when allocating capital.

Low-price/book companies will not necessarily be delisted, but a weak return on equity will lead them to become potential targets.

In early 2024, it upped the ante by publicly naming the companies that have complied with its new rules. Conversely, the companies that haven’t met the new standards of the exchange will essentially be shamed into submission.

Now that the pressure is on these low price/book companies, I think they’ll finally take action. They’ll try to improve the profitability of businesses, sell underperforming subsidiaries, raise their valuations through greater investor communication, hike dividend payout ratios further, and sell their cross-shareholdings.

5. Early signs of success

The Tokyo Stock Exchange’s reforms are already bearing fruit. For example:

- The share of Japanese companies with two or more independent directors has climbed from 22% in 2014 to 99% today.

- The share of companies with investor materials in English has climbed from 80% in 2020 to 97%.

- Cross-holdings have reached a record low.

- And the number of companies announcing buybacks last year rose to 992 - a huge number compared to the 3,000 or so companies listed in Japan.

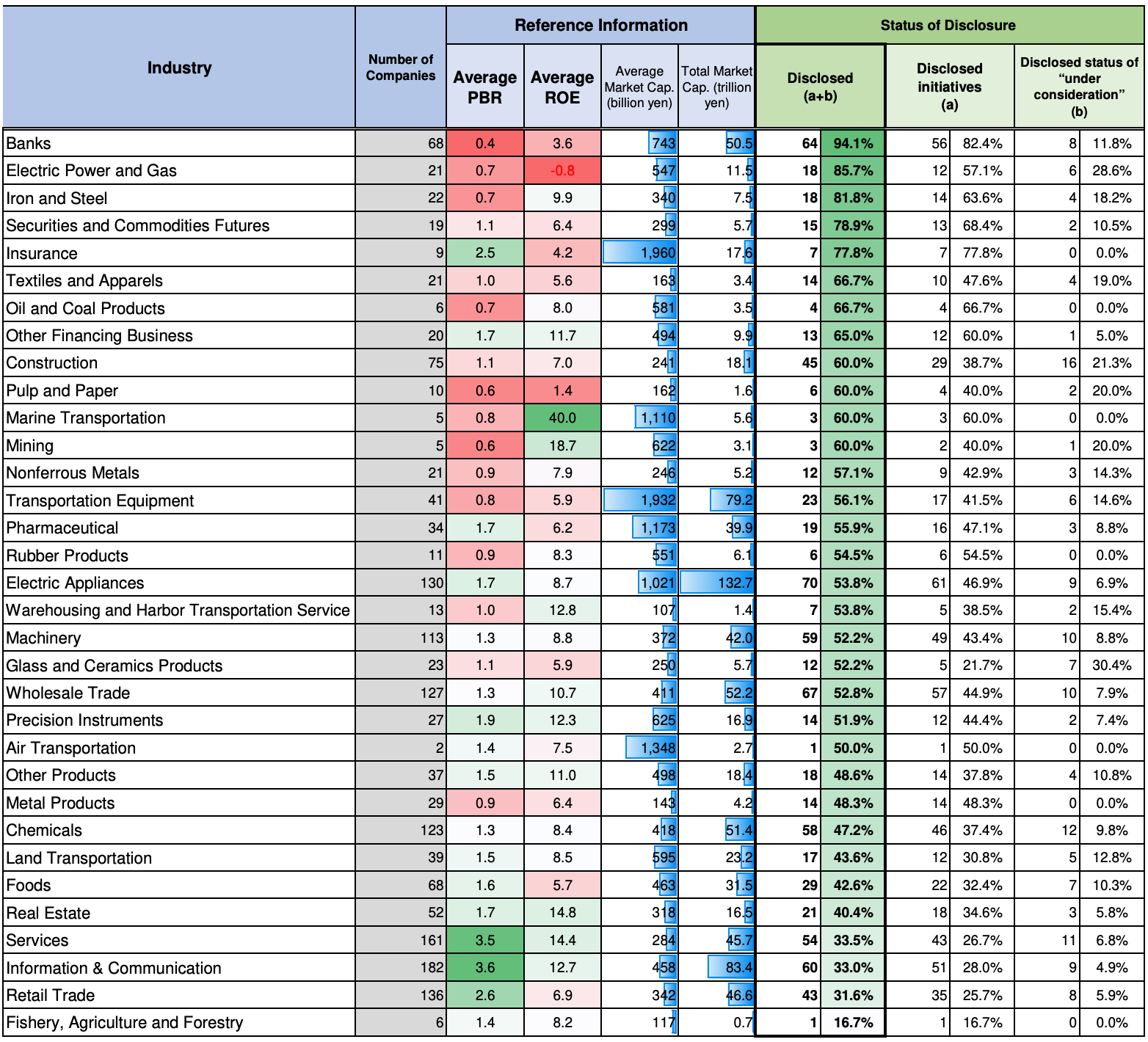

Of the 1,650 companies listed on the Prime Market, roughly 40% have announced steps to improve their capital allocation. For the Standard Market, the numbers are less impressive, with only ~19% having announced or said that they’re considering some measures to comply with the new rules. A few examples of such companies:

- Electronics company Takachiho Koheki set a goal of returning all profits to shareholders through dividends until it achieves its target return on equity of 8%.

- Kyocera announced a share buyback and a plan to exit low-margin businesses.

- Kansai Paint pledged to cut cross-shareholdings and boost returns to investors.

- Oil distributor Idemitsu set a return on equity target of 8% and revised it to 10%.

So far, the sectors with the greatest disclosure have been the financial services sector and energy. Conversely, retailers and IT companies have not been as keen to submit disclosures on how they’re planning to improve their capital allocation:

In any case, investors seem optimistic. Singapore-based activist investor Yoshiaki Murakami said in a recent interview that the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s push for better capital allocation will help them in their crusade against entrenched management teams. A visit by Warren Buffett to Japan in April 2023 also helped improve investor sentiment. He’s looking to buy more Japanese companies.

And the Tokyo Stock Exchange is not standing still. More measures will be released regularly. Expect more companies to be shamed if they fail to live up to the now-higher standards of the exchange.

6. Potential beneficiaries

The last section of this article is only available to premium subscribers. To read on, please subscribe by clicking the button below: