Table of Contents

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

- Corporate governance is a dry subject, but nonetheless important.

- It deals with managing conflicting interests between shareholders and insiders, and maximizing the value of the company.

- I argue that best practices include 1) small boards, 2) a balance between insiders and independent director,s 3) insiders having a sizeable stake in the company,y 4) presence of a nomination committee, 5) pay-for-performance CEO remuneration,n 6) no dual class shares, 7) no takeover defenses and 8) limited cross-shareholdings.

- In the Asia-Pacific region, protections for minorities have improved dramatically, especially in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. In Emerging Asia, legal protections are weaker, making it even more important to pay attention to the alignment of interests. You don’t want to be completely in the hands of corporate insiders.

I spent part of the last week reading through Bob Tricker’s textbook Corporate Governance. It’s an incredibly dry but helpful 500-page tome about the ins and outs of corporate governance.

In this post, I want to provide the main takeaways from that book, along with a tentative checklist that you can use to assess the quality of a company’s corporate governance.

Table of contents

1. The basics of corporate governance

2. Corporate governance around the world

3. An eight-step scorecard

3.1. Small board size

3.2. Balanced ownership concentration

3.3. Balanced board independence

3.4. Nomination committees

3.5. Pay-for-performance

3.6. No dual-class shares

3.7. No takeover defenses

3.8. No cross-shareholdings

4. Conclusion1. The basics of corporate governance

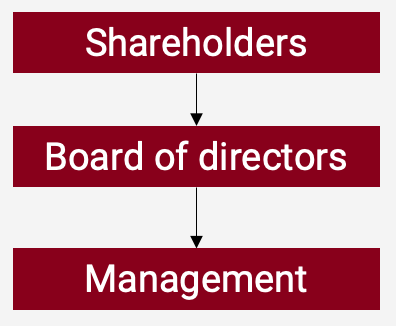

The term “corporate governance” is about ensuring that a company is run in the best interests of its shareholders.

They exercise control by electing a board of directors, which then sets the company's strategic direction and supervises the management team.

In the past, people conducted business as sole traders or through partnerships. The owner and the business were the same legal entity. And if it failed, the owner became liable for the debts incurred.

That all changed in 1855, when Britain began allowing companies to be established as limited liability companies. These companies were incorporated as separate legal entities, capable of entering into contracts and maintaining their own accounts. And most importantly, owners were not personally liable for the company’s debts beyond the amount they had invested in the business.

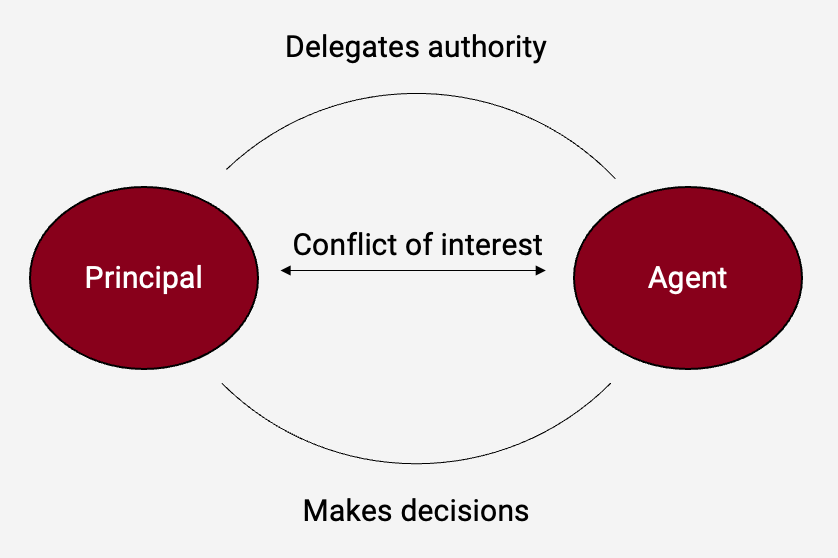

However, a conflict of interest then arose. How could the owners make sure that management would make sensible decisions and not take unnecessary risks with their money?

This is at the heart of the principal-agent problem — principals, such as shareholders, delegate authority to agents such as company management teams. Insiders know more about the business, so they’re in a position to take advantage of shareholders.

So checks and balances are needed. These include:

- Company law: How companies are formed, governed and dissolved

- Securities law: How companies can issue securities, and how these can be traded. For example, public companies are allowed to offer shares to the general public, whereas private companies are not.

- Company constitution: a document specifying how the company should be governed: the company’s objective, information about the share classes, paid-up capital, etc.

The company law in each country codifies shareholder rights. Such rights include receiving dividends, attending annual general meetings (AGMs), receiving disclosures about the business's performance, electing directors, and voting on important matters such as mergers and acquisitions.

In practice, shareholders primarily exercise control through AGMs. These are to be held yearly. The board presents the company’s financial accounts to shareholders. Meanwhile, shareholders elect a new board, approve dividend payments and appoint a new auditor.

Sometimes, shares are owned by a complex chain of intermediaries, and voting is done on behalf of other shareholders. That’s why documents are sent to shareholders well in advance of the AGM, allowing them to make informed decisions about how to vote. These documents are known as proxy materials, as they allow shareholders time to appoint somebody else to vote on their behalf.

At the AGM, shareholders elect boards of directors, which typically include:

- A Chairman, who sets the agenda of board meetings, facilitates discussion and serves as a public face of the company

- Executive directors, company insiders working full-time in executive positions and helping the board make better decisions

- Independent non-executive directors (INEDs) are typically older individuals with extensive experience in the industry. They’re brought in to provide new perspectives and act as a counterweight against the interests of insiders

- A company secretary, who prepares the agenda, files annual returns and sometimes communicates with investors about how the business is doing

While listed entities are “limited liability companies”, it doesn’t mean that directors’ liabilities are limited. If they fail to obey company laws or mislead auditors, they can be punished. In China, they can even face the death penalty. So it’s not a responsibility to be taken lightly.

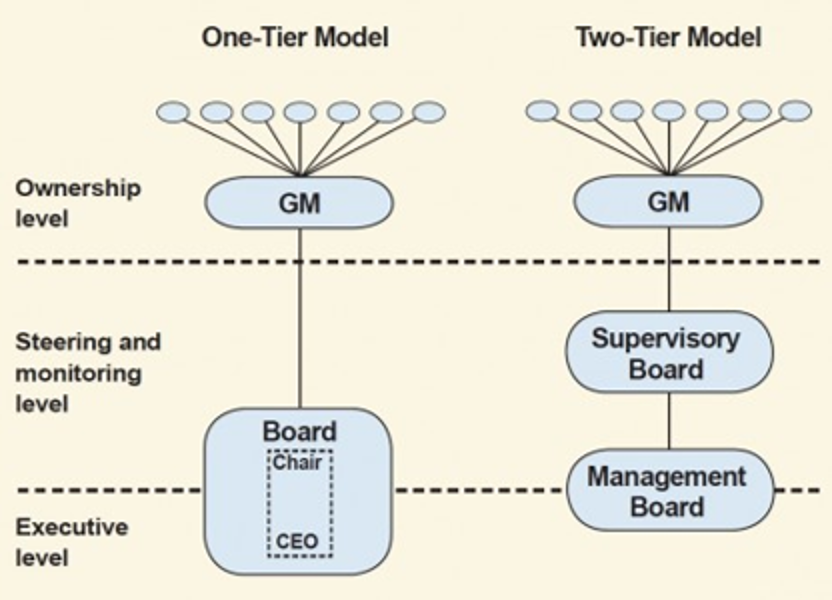

There are two types of board structures: unitary boards and two-tier boards. In the United States, shareholders elect boards that include both executive and non-executive directors and the Chairman and CEO positions are typically combined. In other countries, such as Germany, the board has two tiers: shareholders elect a supervisory board, which then elects a management board.

There are pros and cons to each approach. In unitary boards, you could argue that executive board members are giving scorecards to themselves. However, on the other hand, they have more knowledge about the business and are in a better position to make informed decisions.

Modern boards will also typically be supplanted by three subcommittees, comprised entirely of independent directors:

- Nomination committees, which nominate new board members who are then ratified at the AGM

- Remuneration committees, which determine the salaries of directors and senior executives

- Audit committees, which serve as the contact point between the board and the auditor

In a true shareholder democracy, anyone should be able to propose a new director for the board. But in practice, including the United States, director nominations are typically done by the incumbent board and then approved at the AGM. In other words, boards essentially elect themselves. That’s problematic.

Once elected, the board sets the direction of the company, often in conjunction with management. This direction will be reflected in the company’s mission statement or long-term plan.

The board is also responsible for key disclosures to investors. Listed companies often establish investor relations departments to address questions that investors may have.

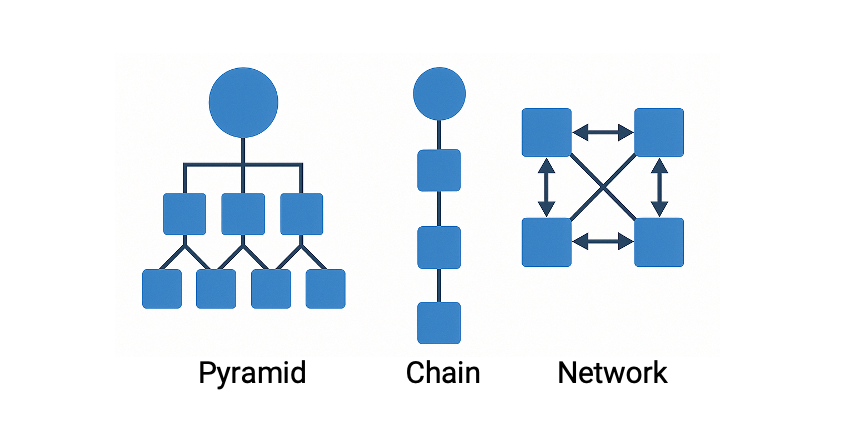

Once set up, companies can own other companies in long chains, and even shares in themselves (treasury shares). Here are some common corporate structures:

Specifically:

- Pyramids are when a single holding company at the top owns a set of subsidiaries, which in turn own other subsidiaries. Most listed companies are structured like this.

- Chains are when a single holding company owns subsidiaries in a straight line down to an operating company. Magnificent Hotels in Hong Kong come to mind, as do the typical HoldCo/OpCo structure in South Korea.

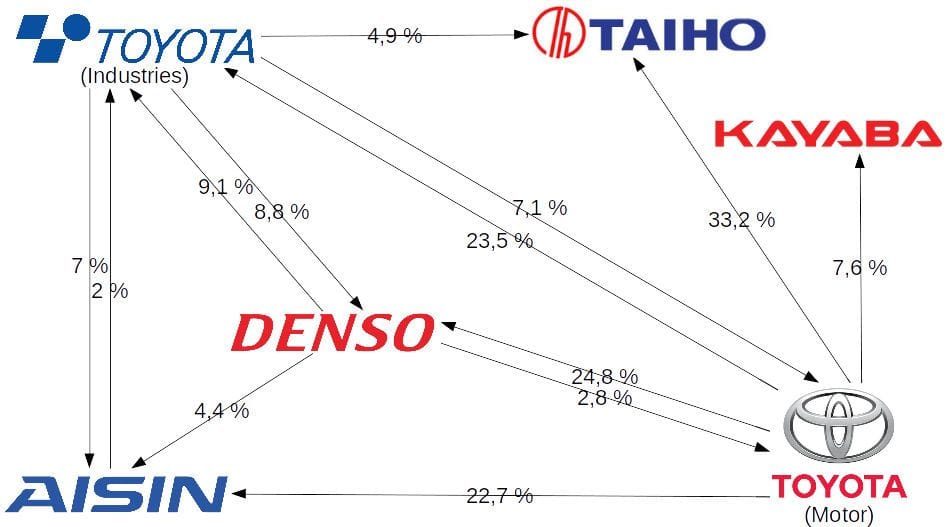

- Networks are when a set of companies own shares in each other, perhaps to fend off hostile predators and reduce the influence of outsiders. Keiretsus in Japan and Chaebols are examples of network structures.

It’s usually best for minorities if the corporate structures are simple. If there are listed companies in several parts of the hierarchy, conflicts of interest will arise between each of these minority groups. Even if independent directors run the board at the top, they’ll look after the interests of their own shareholders, not the minorities of each subsidiary company.

So why do companies end up with these complex structures? Sometimes, due to years of mergers and acquisitions. At other times, due to tax or payroll.

However, it can also be due to controlling shareholders seeking to control a broader range of assets. If there are minorities in each step of the hierarchy, then a small stake, say 5%, can be used to control, for example, 30% of the operating company at the bottom. This type of behavior is clearly problematic.

Equally problematic is the use of dual-class shares, technically known as “weighted voting rights”. Dual-class shares allow insiders to control a majority of the votes, despite owning only a small portion of the cash flow rights. If insiders fail to perform, it will be virtually impossible for minorities to remove them. So pay attention to the corporate structure.

2. Corporate governance around the world

As mentioned earlier, companies are governed by company law and securities law. However, companies need incentives to follow these laws; otherwise, they’re not worth the paper they’re written on. Enforcement is facilitated through independent judicial systems, robust regulators, and active stock exchanges. And the rules need to be in favour of minorities, not vested interests.

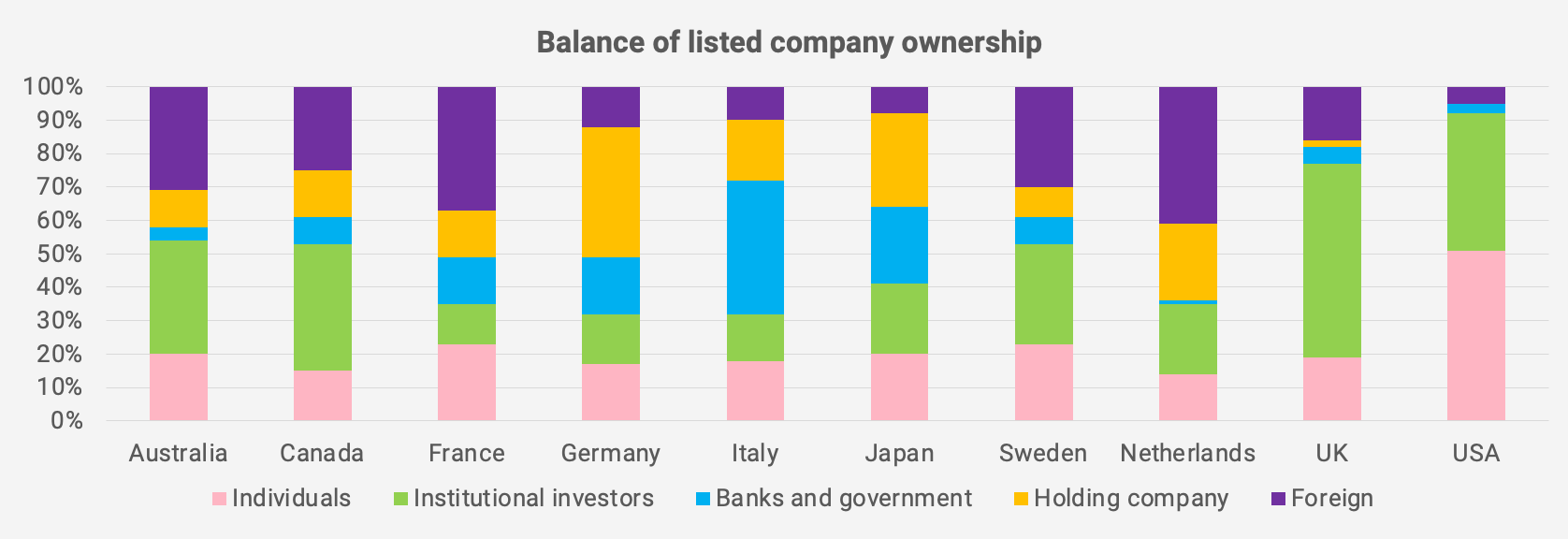

The identity of the actual shareholders also influences governance. The distribution of ownership is not the same across all countries, as you can tell from the following chart:

In the United States and the United Kingdom, for example, listed companies are owned by institutions and individuals. Conversely, in Italy, listed companies are more often owned by banks and family holding companies. They have their own interests, and don’t always align with those of minorities.

US regulation is known to be rules-based. Investor protections, auditing requirements, and disclosures are all federal responsibilities. And if companies don’t live up to them, they’ll face legal repercussions. The same is true for China, South Korea, India, Thailand and Vietnam.

In other parts of the world, such as the United Kingdom and its former colonies, corporate governance rules tend to be principles-based. Companies are encouraged to comply with corporate governance codes; otherwise, they must explain why they have not. This approach is commonly referred to as “comply or explain” regimes. The benefit of this approach is that it provides flexibility. But on the other hand, many companies will do the bare minimum and leave minorities in the dust. In Asia, principles-based regimes include Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, Malaysia and the Philippines.

Another distinction between board practices is between unitary boards and two-tier boards:

- Unitary boards are used in the United States, the United Kingdom and much of the rest of the world. Shareholders elect a single board which then controls management.

- Then there’s the two-tier board system, as practised in continental Europe, Indonesia and historically, in Taiwan. These have supervisory boards elected by shareholders, and the supervisory boards then elect executive boards. In Germany and the Netherlands, employee unions appoint part of the supervisory boards.

In Asia, there are also cultural and country-specific peculiarities. For example, in Japan and parts of East Asia, the culture tends to emphasize social cohesion. Confrontation tends to be frowned upon. That could be one reason why minorities tend to have less influence in Japanese corporations. Boards tend to side with the management teams they have elected.

Another peculiarity is the use of cross-shareholdings in Japan and South Korea. Companies own shares in each other in complex networks called keiretsus, often based around banks that lend to them. By forming these networks, they ensure access to debt-based financing. And they ensure that outside investors won’t be able to challenge their grip on power.

China, Vietnam and other communist nations have their own peculiarities. In these countries, courts serve the state and the party. Within China’s two-tier boards, members of the Communist Party committees often chair the supervisory board, ensuring the companies are aligned with the Communist Party's interests. And under Xi Jinping, all listed companies are now required to have communist party committees, which serve as shadow directors able to hire and fire senior management teams.

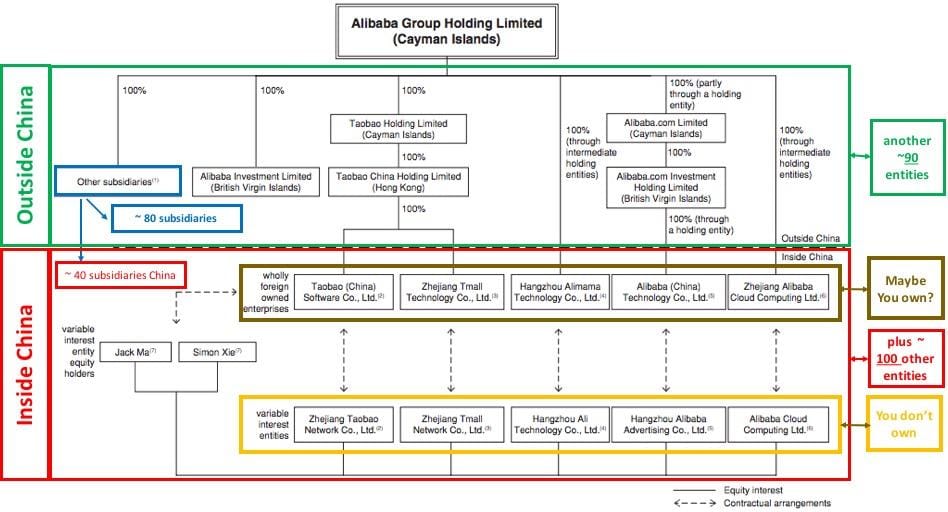

In China’s case, additional conflicts of interest emerge from the fact that many overseas-listed Chinese companies are structured as variable interest entities, where the operating companies are governed by separate boards completely disconnected from the foreign shareholders.

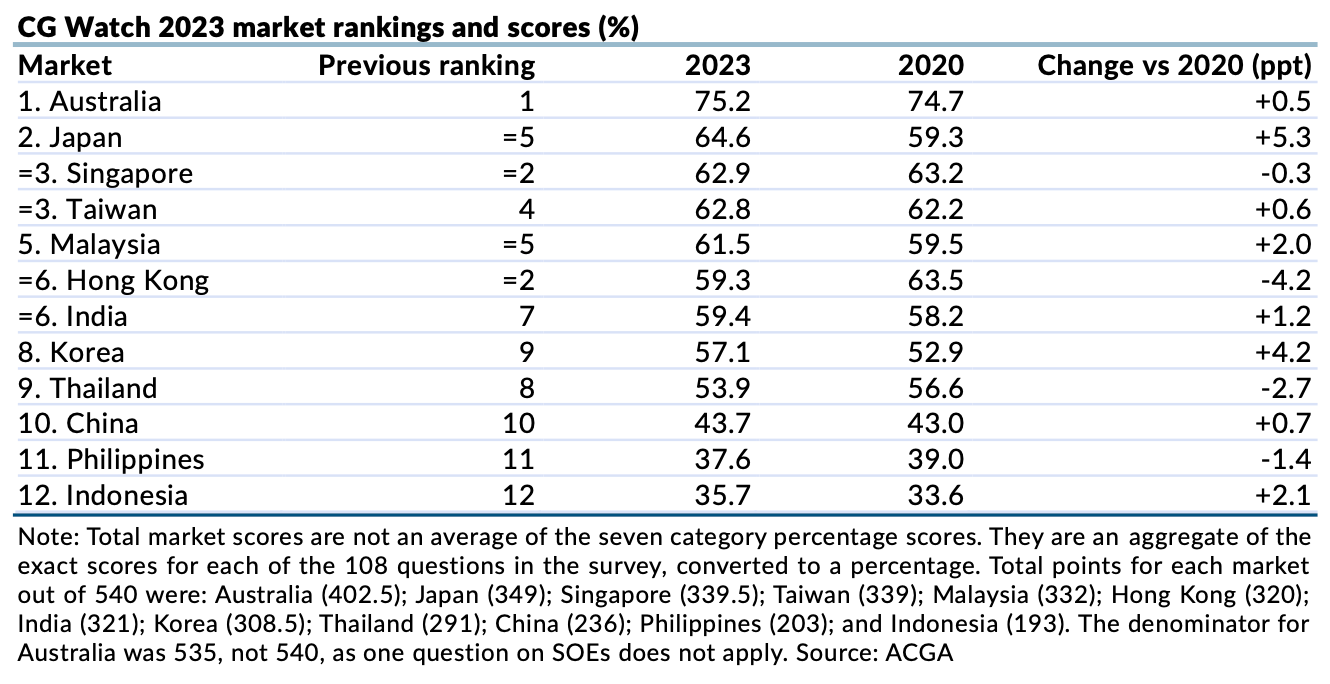

In its latest 2023 report, the Asian Corporate Governance Association (ACGA) ranked corporate governance as the strongest in Australia, Japan, and Singapore. Minority protections have improved significantly, especially in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Here is a summary of the strengths and weaknesses of each jurisdiction. As you can tell, the main issues include takeover defenses, dual class shares, cross-shareholdings, poor enforcement and an inability to stop companies from engaging in related party transactions:

As you can see, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Malaysia have robust protections for minorities. But in the case of Hong Kong, companies listed there often have their primary operations in other jurisdictions, making it challenging to stop related party transactions at unfavorable prices.

While Japan and South Korea have strong minority rights on paper, cross-shareholdings and tax policies frequently prevent minority interests from being taken into account.

Meanwhile, Indonesia and the Philippines lag when it comes to enforcement, with minority abuses rarely addressed in courts.

Finally, China and Vietnam have their issues, with a lack of independent courts, and in the former case, communist party control setting policy behind the scenes.

3. An eight-step scorecard

What if you’re tasked with assessing a company’s corporate governance policies? What should we consider to be best practices?

I’ve gone through the literature and come up with a list of eight metrics that I think are worth tracking:

3.1. Small board size

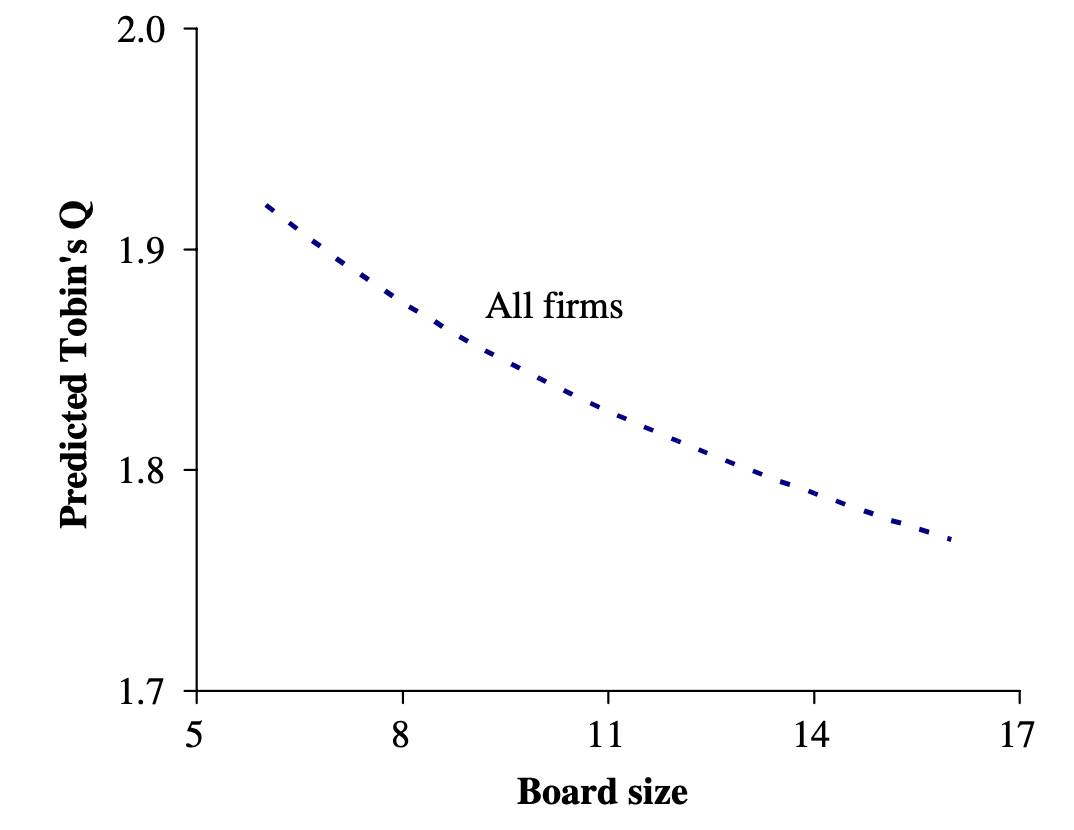

Smaller boards are generally better. A European study by Conyon and Peck (2010) found a negative relationship between board size and return on equity, as well as market valuations. The more people you add to the board, the worse the performance gets.

The explanation seems to be that each extra director raises coordination costs and slows down decision-making. Large board meetings may encourage passivity. And they may allow CEOs to dominate meetings more than smaller groups might.

At the same time, there is evidence that in complex companies with significant research & development or in regulated industries, larger boards may add some value.

So, a board of no more than 7-9 directors is probably ideal for most companies. And if a company is highly complex, then up to 12 directors is perhaps okay.

3.2. Balanced ownership concentration

McConnell & Servaes (1990) showed that insider ownership between 30-50% leads to a higher market valuation for listed companies:

Why? Because insiders typically have strong incentives to maximize shareholder value. But beyond a certain level, the risk of unchecked empire building and minority abuse starts to build.

When it comes to founder ownership concentration, the sweet spot appears to be somewhere in the middle, around 30-50%. This result seems to be consistent across both developed and emerging markets.

3.3. Balanced board independence

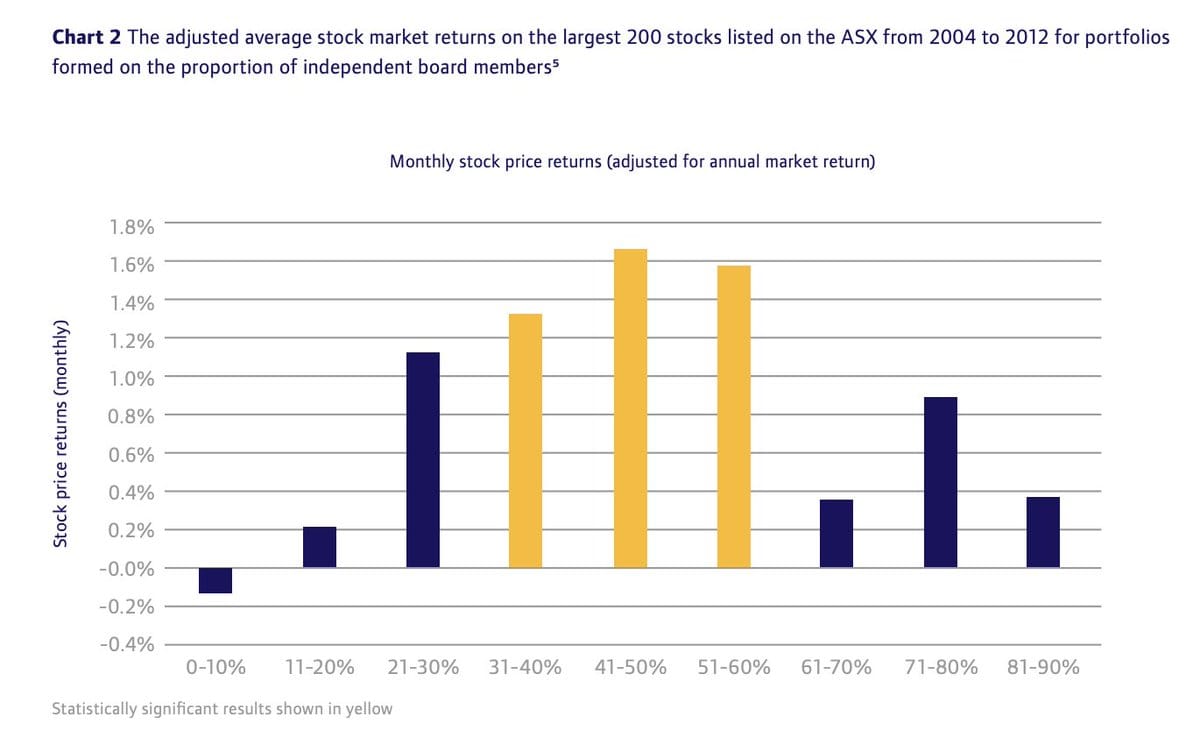

As Blackbull Research recently pointed out, fully independent boards are not always ideal. While independent board members can stop the empire-building tendencies of corporate insiders, they’re also less informed about the business. And as Louis-Vincent Gave of GaveKal has repeatedly pointed out, many of them are only out to collect salaries and “cover their asses”, to use a technical term.

This paper from Alex Frino supports the view that more independent directors are not always better. Using data from the ASX, he showed that companies with balanced boards of 40-60% independent directors tend to outperform when it comes to market-adjusted stock price returns.

3.4. Nomination committees

Another study by Agyemang-Mintah (2015) in the UK showed that financial institutions with nomination committees led to higher market returns and higher return on equity. And especially when members brought relevant expertise to the committee.

Another study by Aldegis et al (2023) from Jordan (of all places) showed that non-financial companies with nomination and remuneration committees showed a positive and significant relationship with market valuations.

The reason is that with a nomination committee, insider board capture is much less likely. And especially if the nomination committee is staffed by independent board members with industry expertise.

3.5. Pay-for-performance

The most effective way to remunerate CEOs is by linking their compensation packages to total shareholder returns over the long term. And the pay shouldn’t be too high.

According to this Harvard Law School article, CEO incentives that only pay out if the company beats a peer group’s total shareholder return tend to lead to higher stock prices.

Longer vesting periods are better. Gu, Lu & Yu’s (2023) research shows that longer vesting terms lead to lower perceived crash risk for any given stock. Edmans, Fang & Lewellen (2014) demonstrated that equity grants with short-term vesting periods led to managerial myopia.

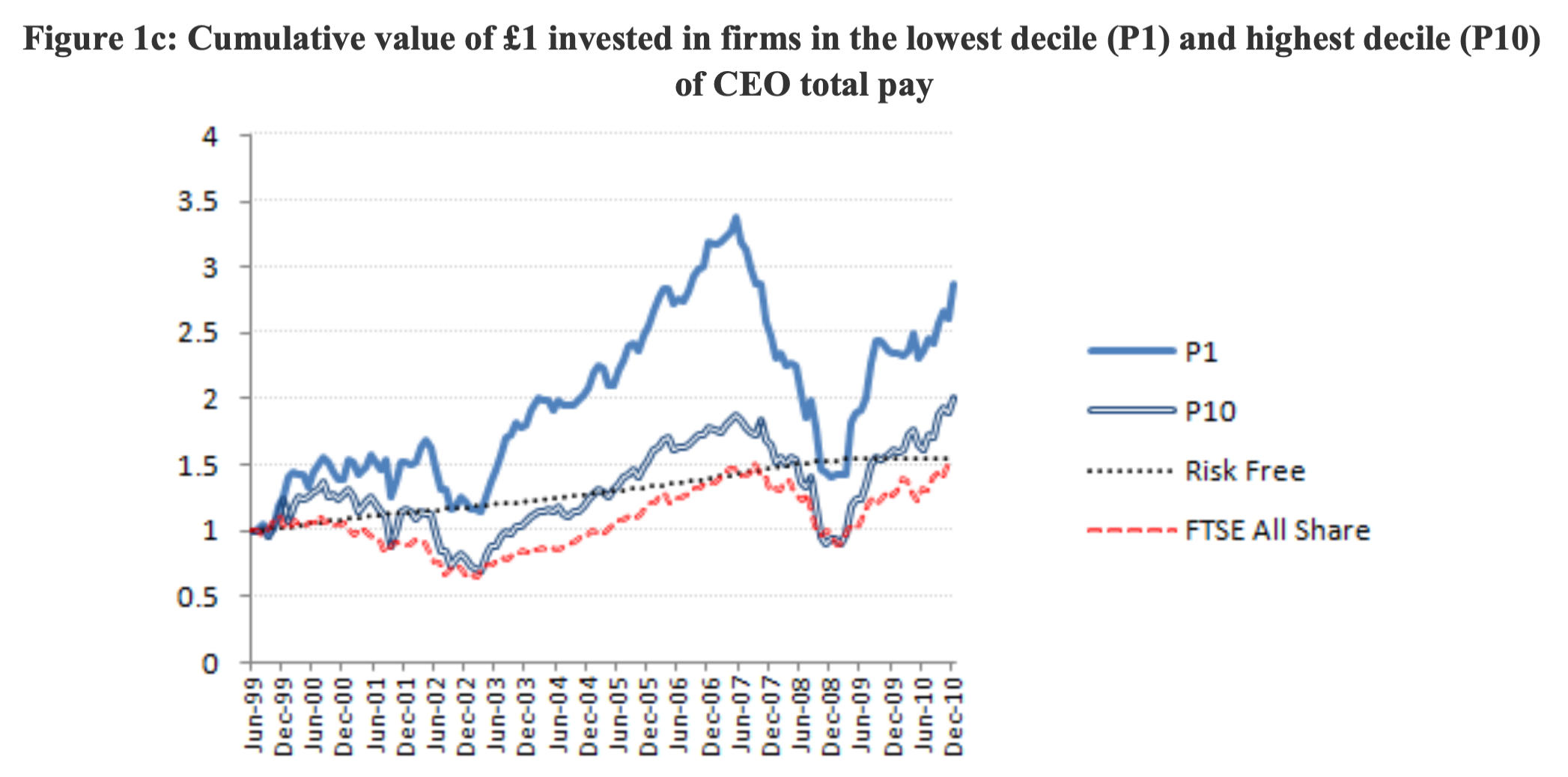

And lower CEO pay is probably better, too. Balafas & Florackis (2014) showed that LSE-listed firms that pay their CEOs the least enjoy positive abnormal returns.

3.6. No dual-class shares

Dual-class shares weigh on market returns over the long run. While dual-class shares might help brilliant companies enter the market, they can eventually become a burden.

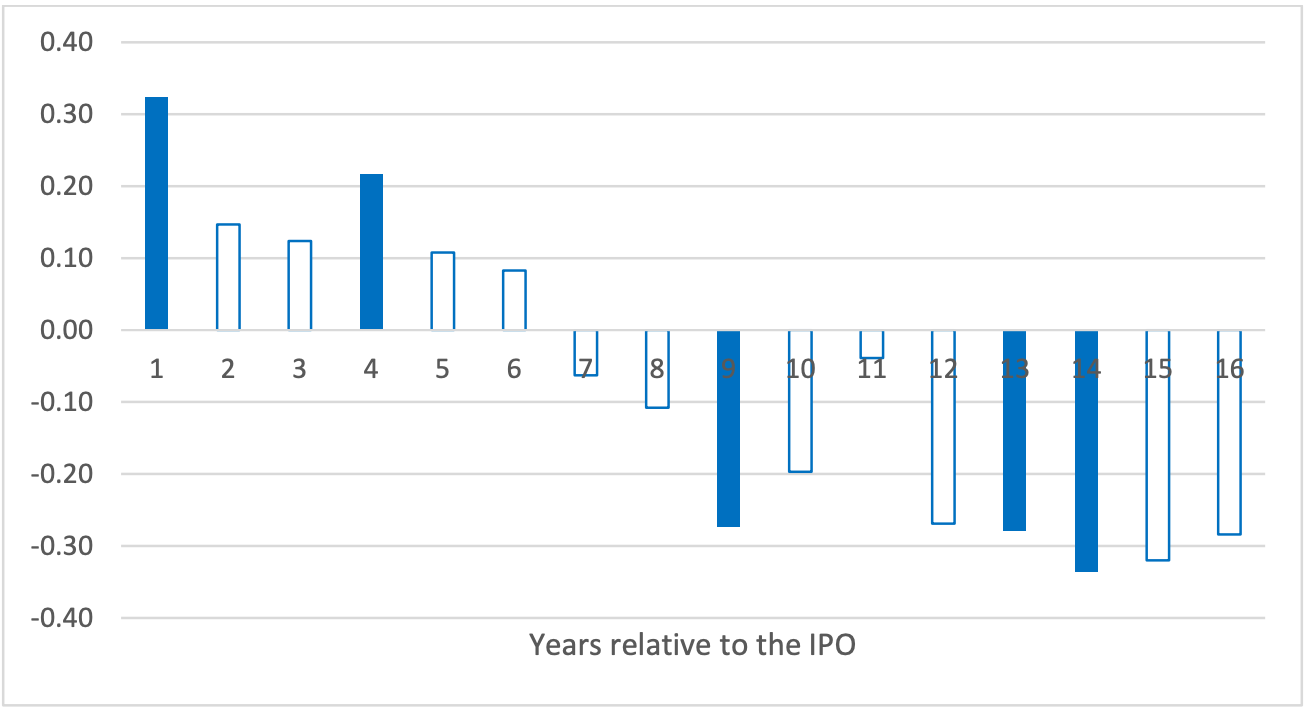

Smart & Zutter (2003) showed that dual-class IPOs underperformed single-class IPOs by -26% over the three years following the IPO.

Cremers, Lauterbach & Pajuste (2018) showed that dual-class IPOs enjoy valuation premiums during their IPO, but this premium eventually turns into a discount:

Furthermore, an ISS/IRRCI study showed that multi-class stocks underperformed relevant benchmarks on all time horizons longer than 1 year.

The explanation is obvious: brilliant entrepreneurs have enough bargaining power to create dual-class share structures, but if they start to underperform, minorities will have no way to get rid of them. So buyer beware.

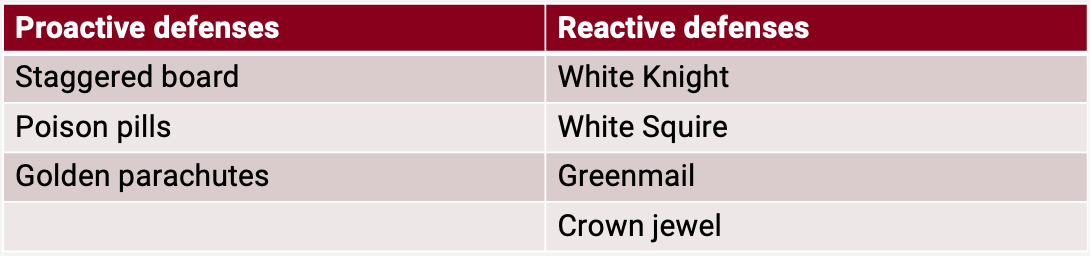

3.7. No takeover defenses

Management teams use a poison pill to defend themselves against hostile takeovers. Whenever there’s a takeover, it allows existing shareholders to buy shares at a discount, thus diluting the acquirer.

Since poison pills entrench management teams and create a failure in the market for corporate control, it’s no surprise that they lead to lower shareholder returns. Malatesta & Walkling (1988) showed that the poison pills lead to -1% to -3% abnormal return on the day of adoption.

Another way for company insiders to protect themselves against hostile takeovers is through the use of staggered boards, which cannot be replaced quickly. Another way to protect against hostile takeovers is through golden parachutes, which provide large payments to management in the event of a hostile takeover.

In any case, Eisdorfer, Morellec and Zhdanov (2023) showed that:

“Distressed firms experience a significant decrease in value and increase in returns and market betas after the passage of anti-takeover laws”

The explanation is that poison pills reduce the likelihood of a takeover at a premium. When companies are acquired, bidders usually pay 25-30% over the last close for a controlling stake, and when poison pills are active, minorities lose this premium.

3.8. No cross-shareholdings

Miyajima & Kuroki (2006) demonstrated that high bank ownership and corporate cross-holdings in Japan lead to lower valuations.

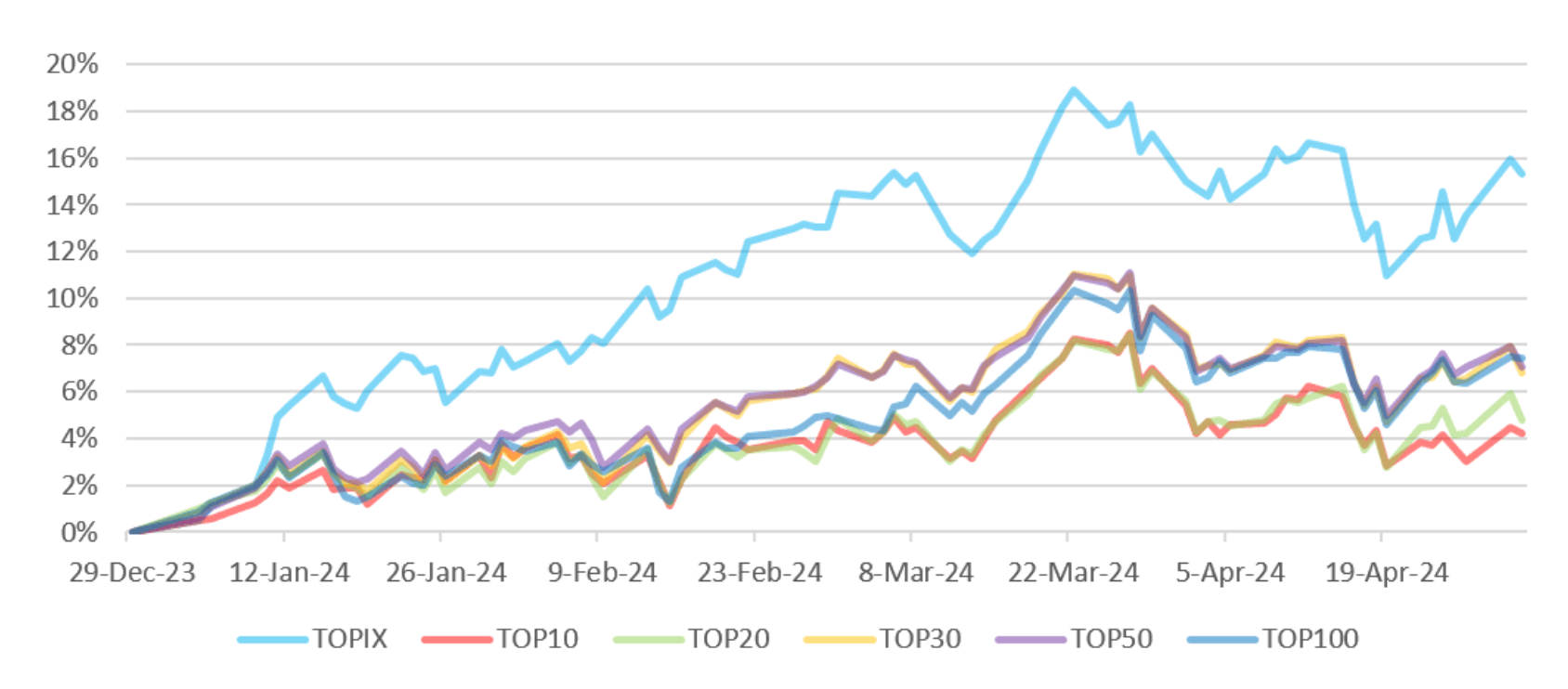

Another study available here shows that stocks with the highest cross-shareholding ratios significantly underperformed the TOPIX in a recent time frame.

A similar result has been seen in Western Europe, with Bennedsen & Nielsen (2004) reporting a negative impact on valuations from a high degree of cross-ownership, though perhaps less so than dual class shares.

4. Conclusion

Corporate governance sounds boring — perhaps because the subject has been taken over by the ESG mafia and box tickers at corporate compliance departments.

But I’m convinced that good governance leads to higher shareholder returns. And if my tentative checklist is as well-designed as I think it is, then you should invest in companies with small boards. They should have a balance between insiders and independent directors. The founders should have a sizeable stake in the company. The board should have a nomination committee. Ideally, the CEO should be rewarded based on shareholder returns, with lengthy vesting periods. Finally, avoid companies with dual-class shares or other takeover defences, including cross-shareholdings. They’re not in the best interests of minorities.

Thanks for reading Asian Century Stocks.

Consider becoming a subscriber! You’ll get 20x high-quality deep-dives per year, thematic reports and full portfolio disclosure — all for the price of a few weekly cappuccinos: