Table of Contents

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may from time to time have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is disclosure and not a recommendation to buy or sell.

EV stocks went vertical during the pandemic and it looks like the speculative bubble is over. For that reason, I thought it might be worth reviewing the sector and making a few predictions.

I will start by looking at the value proposition of buying an EV vs a conventional car, then looking at customer response to new EV models, industry-wide data, a discussion about the industry’s subsidy reliance, and finally, a survey of companies and stocks in the industry.

1. The benefits of buying an EV

Buyers are primarily attracted by a number of key features:

Fast acceleration. Early adopters of Tesla’s Model S were drawn to its fast acceleration, with many reviewers emphasising the hair-splitting experience of accelerating from zero to 60 mph. Conventional sports cars cannot match the acceleration of EVs since EVs operate at instant-full torque. While the average consumer rarely pushes his or her car to the limit, fast acceleration makes a car more responsive and more fun to drive.

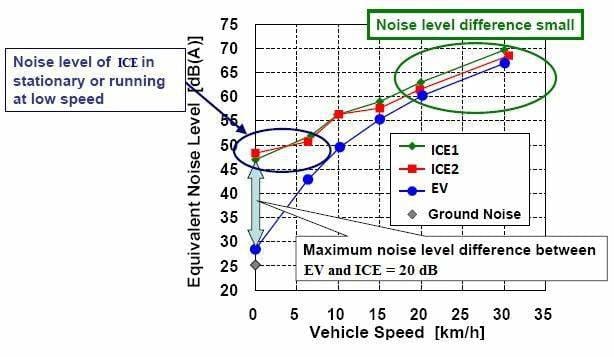

Lower noise. Noise levels are lower for electric vehicles than internal combustion engine vehicles, but only at sub-15km/h speeds. At speeds above 15km/h+, tire noise overwhelms any noise from an engine. Cabin design, therefore, becomes a more important issue in minimising the overall noise level.

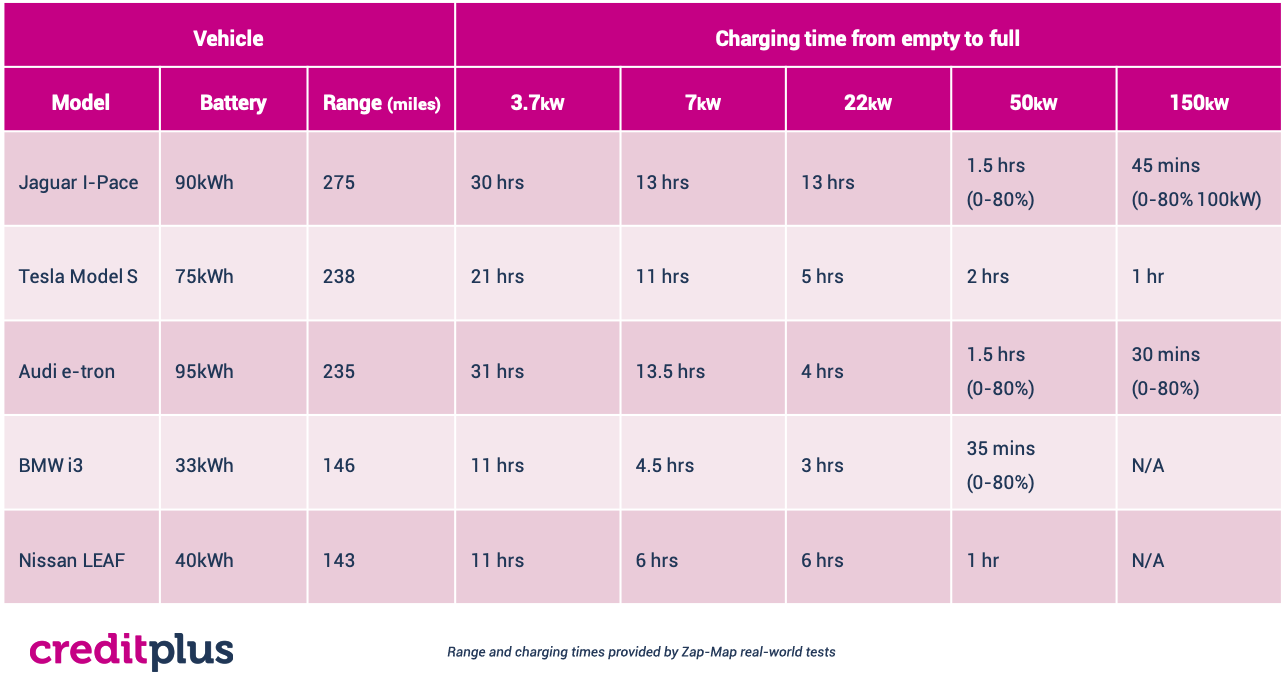

Overnight charging. Roughly 85% of plug-in electric vehicle charging is done at home in the US. Some may view overnight charging as a benefit since consumers can avoid trips to the gas station. With a 7kW level 2 charger, you can expect a close to full charge overnight some of the popular EV models available today (~13 hours, which will give you close to a full charge overnight assuming you don’t drive late at night):

Lower repair costs. US Consumer Reports shows that consumers who purchase an EV can expect to save an average of US$4,600 in repair and maintenance costs over the life of a vehicle compared to a gasoline-powered car.

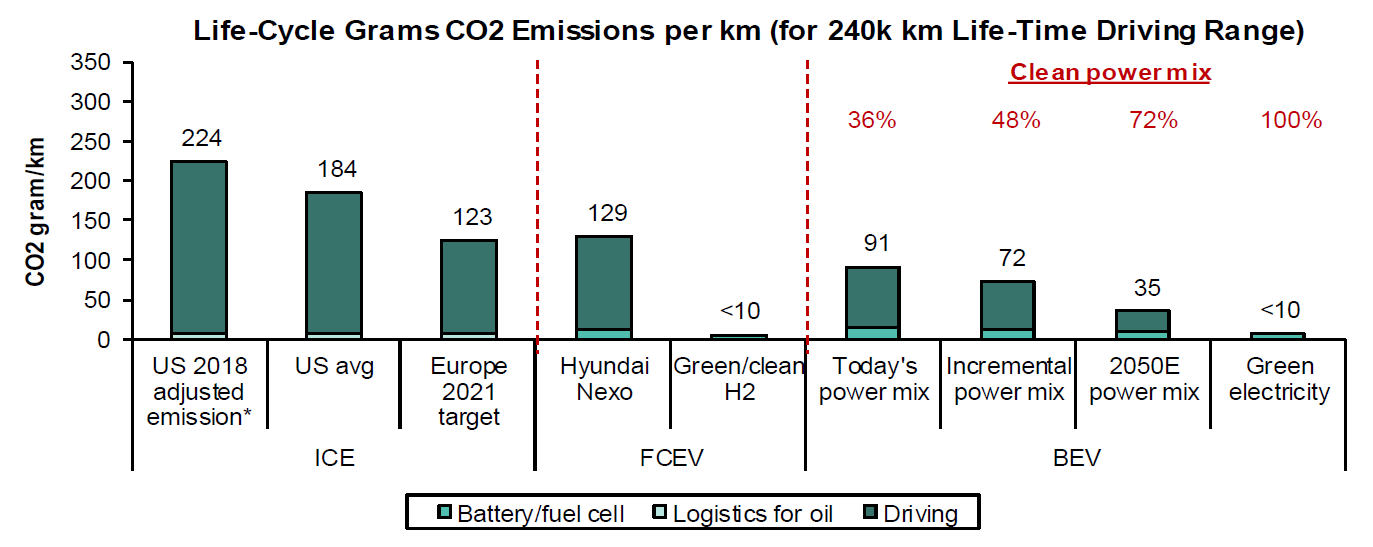

Environmental concerns. Electric vehicles could potentially be more environmentally friendly than conventional gasoline vehicles. At today’s power mix, it seems plausible that life-cycle carbon dioxide emissions for EVs are lower than those of ICE (internal combustion engine) vehicles - though that is not necessarily the case for all countries.

A complement to home solar panels. If your house has solar panels, you might be able to use your EV car battery as temporary home electricity storage.

2. The drawbacks of buying an EV

But there are also several drawbacks:

Reliance on coal and natural gas in a country’s power generation. If EVs are to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, then their batteries must not be charged with electricity generated from the combustion of fossil fuels. But 60% of all electricity generated worldwide comes from fossil fuels (primarily coal and natural gas). Also, Arthur D Little has estimated that over a 20 year period, EVs produce roughly 3x the amount of toxicity as that of a conventional vehicle, potentially impacting both freshwater systems and the human body.

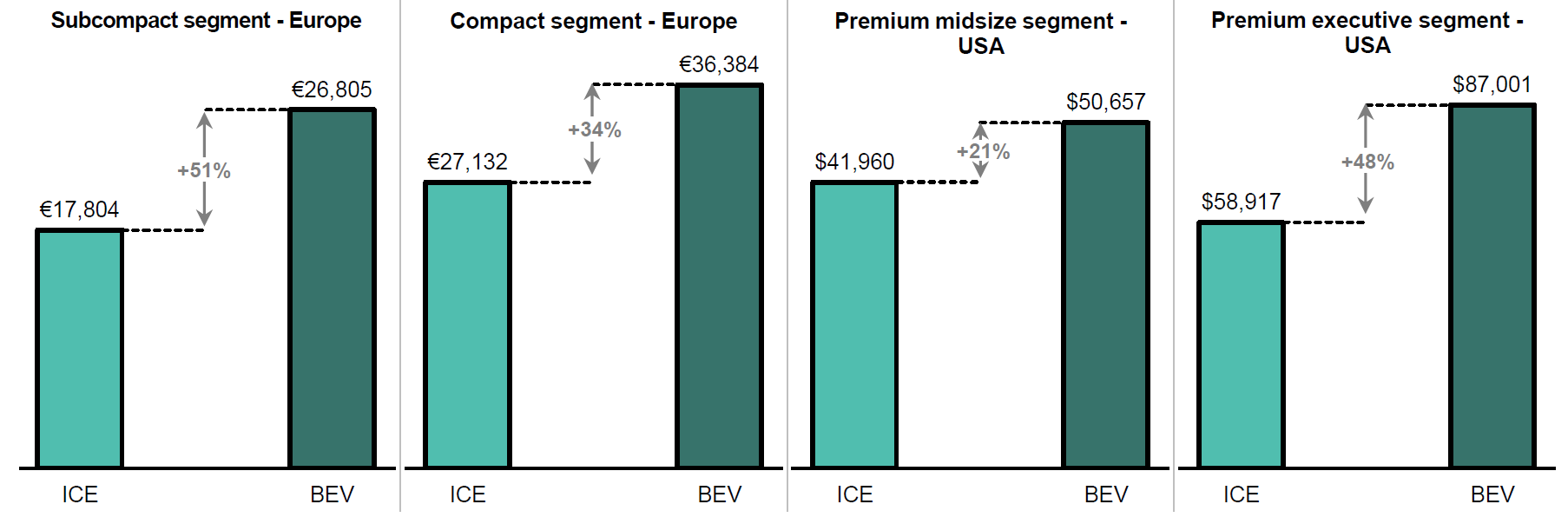

Higher prices. Today’s EVs cost around US$10,000 more than an equivalent ICE vehicle, and EV gross margins are not higher than those of ICE vehicles.

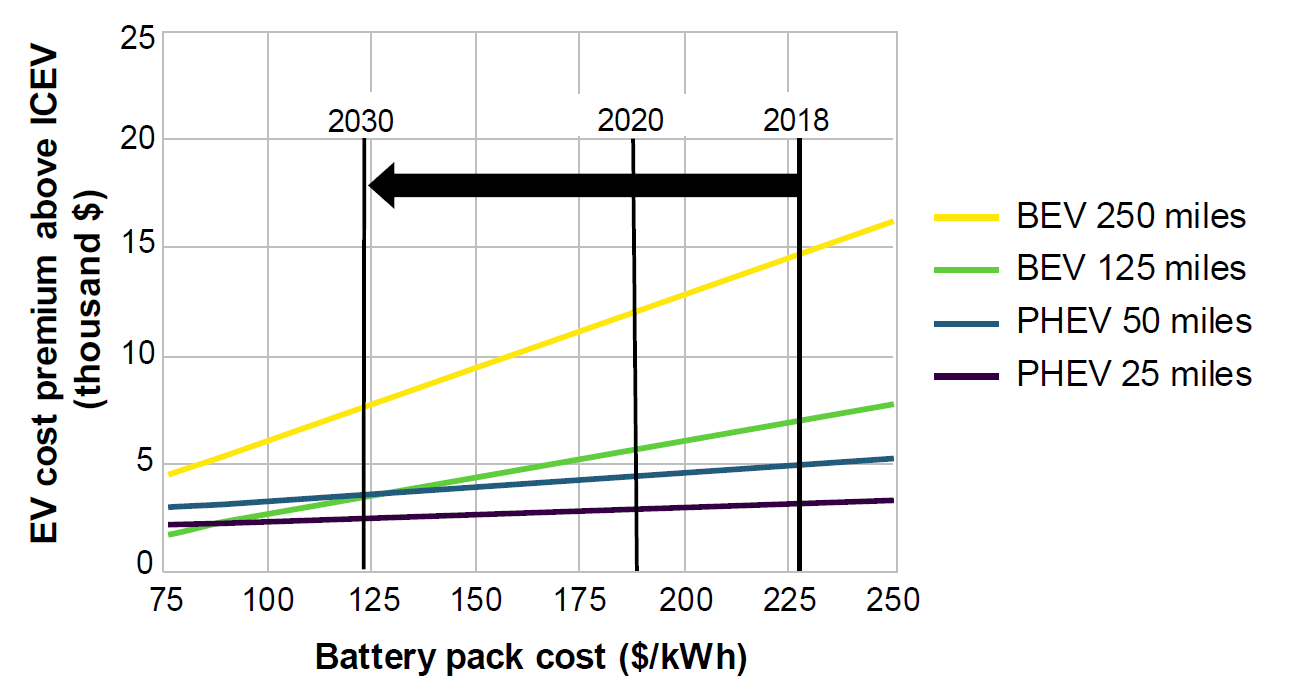

Battery pack prices are expected to drop around 50% between 2018 and 2030, reaching US$124 per kWh by 2030, according to MIT’s Future of Mobility report. It further argues:

“A price target of $100/kWh for widespread EV adoption is very unlikely to be achieved by 2030 with the continued maturation of existing NMC-based LIB technology. The $100/kWh target can be achieved only if mineral prices stay roughly the same as in 2016; however, significant uncertainty remains about the steady-state price of cobalt in the future as demand and supply continue to increase”

With the above assumption of US$124/kWh in battery pack prices, an EV with a 200-plus mile range will remain upwards of $5,000 more expensive than a similar ICE vehicle in 2030:

What could change the equation is a breakthrough in solid-state battery technology. But according to Munro & Associates, neither of the dozens of claims about near-term breakthroughs in the commercialisation of solid-state batteries has shown any real promise.

Weak range. The range of most electric vehicles tends to be 250-300 miles on a full charge. A 2020 Toyota Prius can get 650 miles on a single gas tank.

Lack of charging infrastructure. The majority of the world’s population lives in apartments. Charging infrastructure in many parking garages often do not exist and building such infrastructure would require large investments, presenting the industry with a chicken-and-egg problem. The required density of charging infrastructure for EVs to meet the needs of consumers is around 40/80 plus per 1,000 EVs in cities/rural areas. Most developed countries meet these standards, but investments will be needed to match the growth in the overall EV parc, potentially putting pressure on government budgets in the process.

Slow charging speeds. If you get stuck on the road with no more charge left in the battery, you’ll have to charge outside your home. According to Alternative Fuels Data Centre, the vast majority of chargers outside the home are level 2 chargers (80% in the US). But even with level 3 chargers, it can still take an hour for a decent top-up in battery charge. Roughly 1/5 of individuals in a California survey purchasing EVs between 2012 to 2018 switched back to conventional vehicles due to the inconvenience of charging the battery. Solid-state batteries will be needed to get recharge times down to 15 minutes or less, at which point they will become a lot more competitive compared to conventional vehicles.

Battery degradation. Batteries can lose 30-40% of their capacity in very cold or scorching weather. The pace of battery degradation is disputed but seems to be about 2% per year in a non-linear fashion with faster degradation at the end of its life (total lifespan roughly 8-12 years). Warranties across most major EV models cover retention of at least 70% of battery capacity for eight years, roughly in line with the yearly 2% estimate.

Fire hazards. Data from the London Fire Brigade suggests an EV fire incident rate of 0.1%, more than double that of petrol and diesel cars’ 0.04%. EV battery fires are also more difficult to put out: if a person is stuck inside a vehicle for a significant period of time, he or she is more likely to be subsumed by flames in an EV than an equivalent ICE vehicle.

Reliance on unstable supply of lithium, cobalt and rare earth metals. There are signs that China has been hoarding the supply of rare earth minerals during 2020. Given that China represents close to 90% of the production of rare earths, that opens the question of whether the Western world is becoming too reliant on the supply of minerals from a single country. In terms of cobalt, half of the supply comes from the politically unstable Democratic Republic of Congo.

3. Will electric vehicles take over?

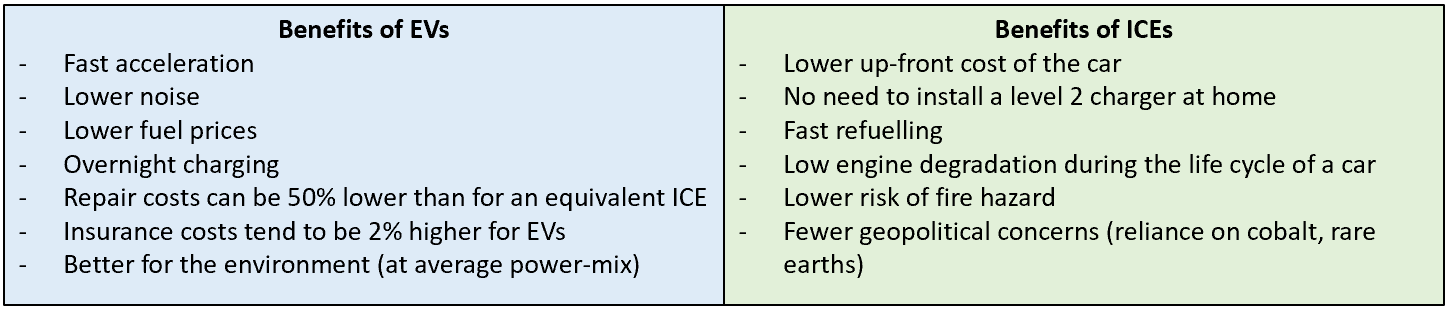

Summing up the above points, it seems clear that the benefits of EVs are fast acceleration and the environmental aspect - at least in countries that rely on clean energy in the power grid. The benefits of ICE vehicless are lower price and convenience in terms of quick refuelling and a longer range.

Most consumers are price-sensitive, however. And assuming flat gasoline prices, it seems unlikely that EVs will reach cost parity before 2030. It might take yet another decade to 2040 before cost parity is finally reached.

That leaves customers weighing the benefits of fast acceleration, low noise, range anxiety, fire hazard and charging convenience. To me, it seems that the net of these features favours ICE vehicles, so even cost parity might not be enough for a wholesale shift to EVs.

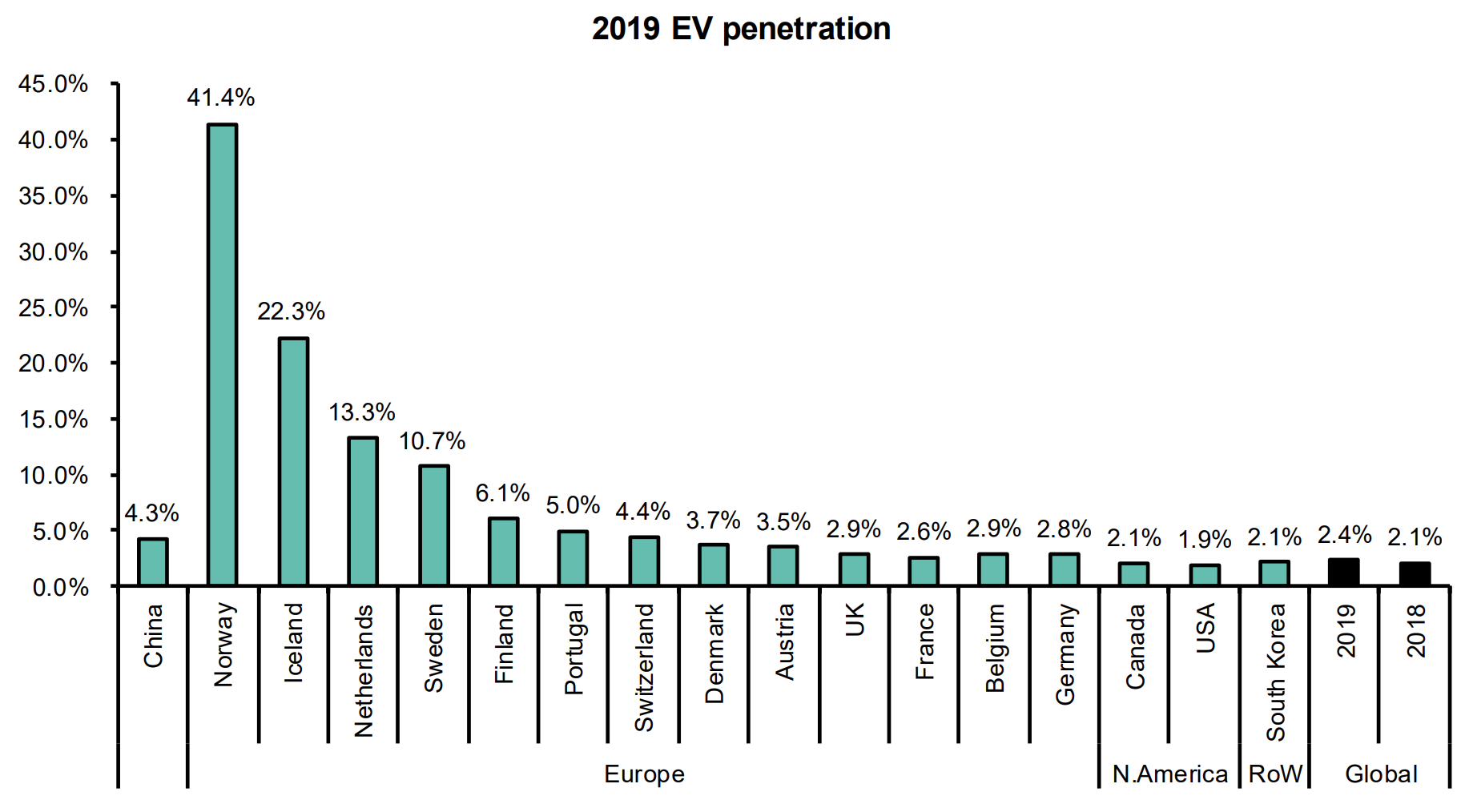

Absent any subsidies and government policies, I, therefore, find it difficult to see EVs making up the majority of new car sales before 2040. Significant subsidies will be needed for the shift to occur at the speed that many investment banks are forecasting. Today, the EV penetration rate is heavily skewed towards countries who are either rich (less price-sensitive) and/or offer generous subsidies, with Norway being the prime example:

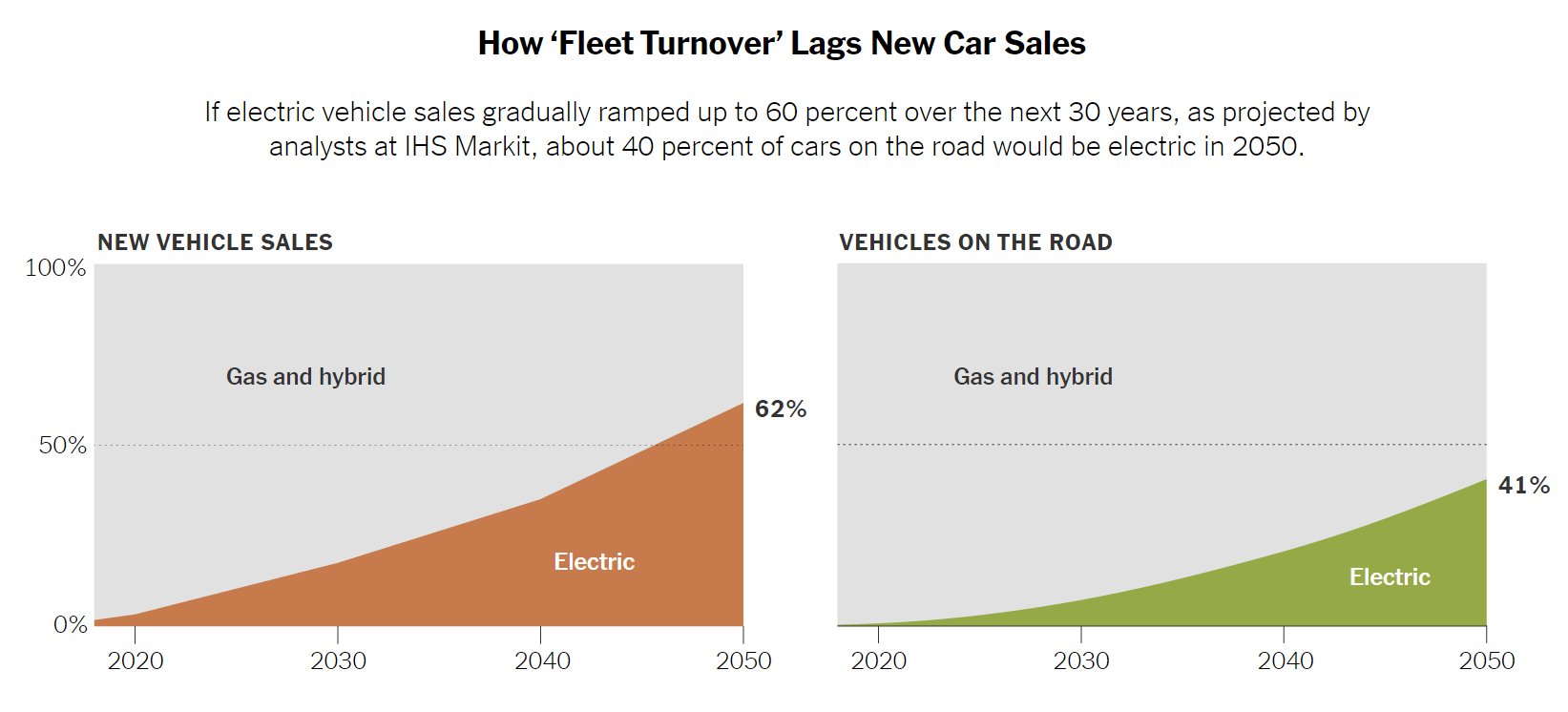

In other words, full-scale adoption of EVs seems unlikely in the near term. The shift is likely to take place over many decades as batteries continue to improve. IHS Markit expects 62% of new car sales by 2050 to be electric over a 30-year shift. That seems like a reasonable estimate to me. Crucially, that would imply an 11% yearly growth in volumes. Impressive, but not explosive. And most of the shift will probably occur when cost parity is reached.

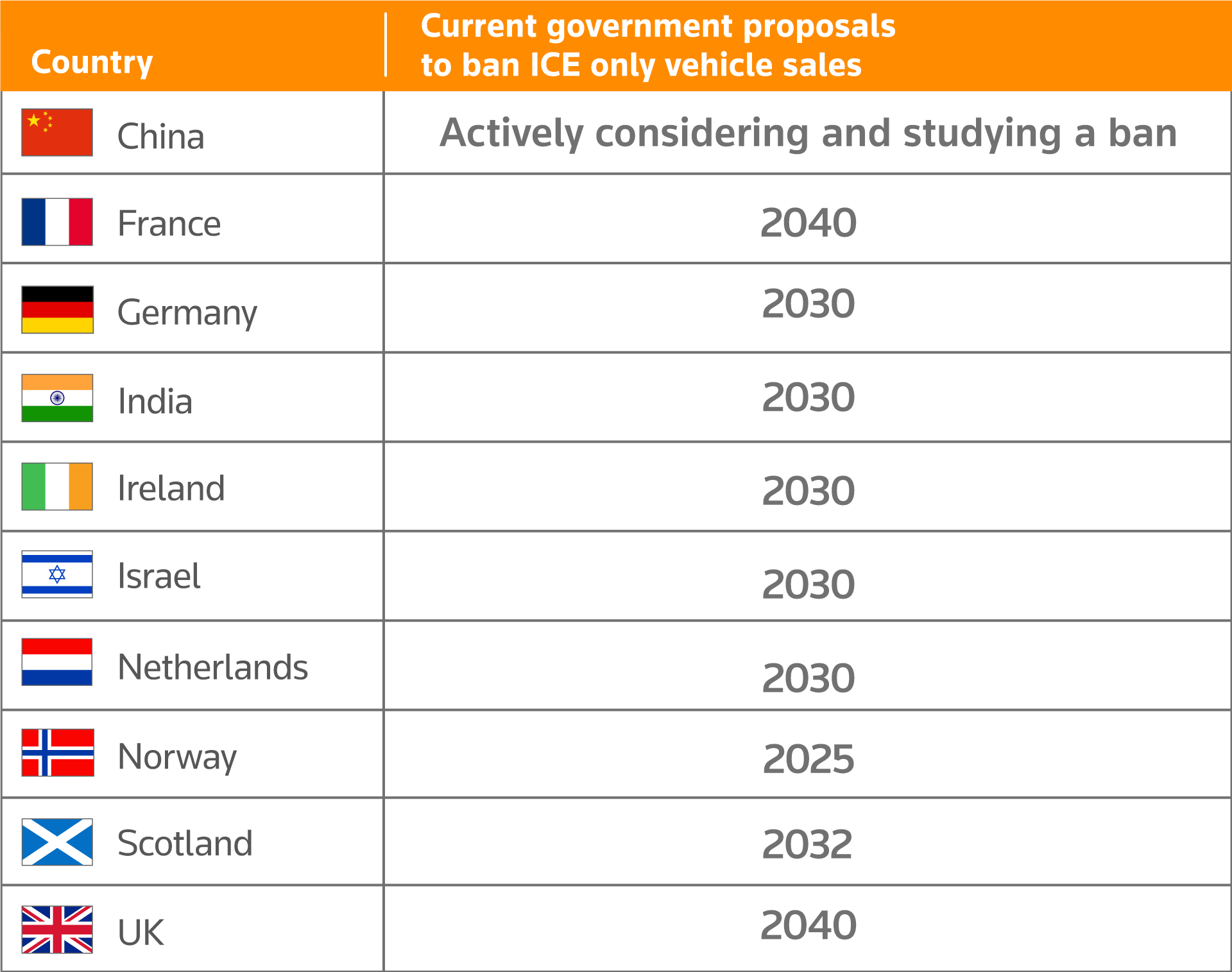

Governments could speed up the process, with many governments setting specific targets banning internal combustion engine vehicles by 2030-2040. The question is whether the general population will support paying higher prices for their transport. Don’t forget the ferocity of the gilets jaunes protests in France in 2018. They were initially sparked by rising fuel prices. Will the average consumer and taxpayer be willing to pay US$10,000 extra for an EV to lower greenhouse gases somewhere around the order of 5%?

4. Measuring customer engagement

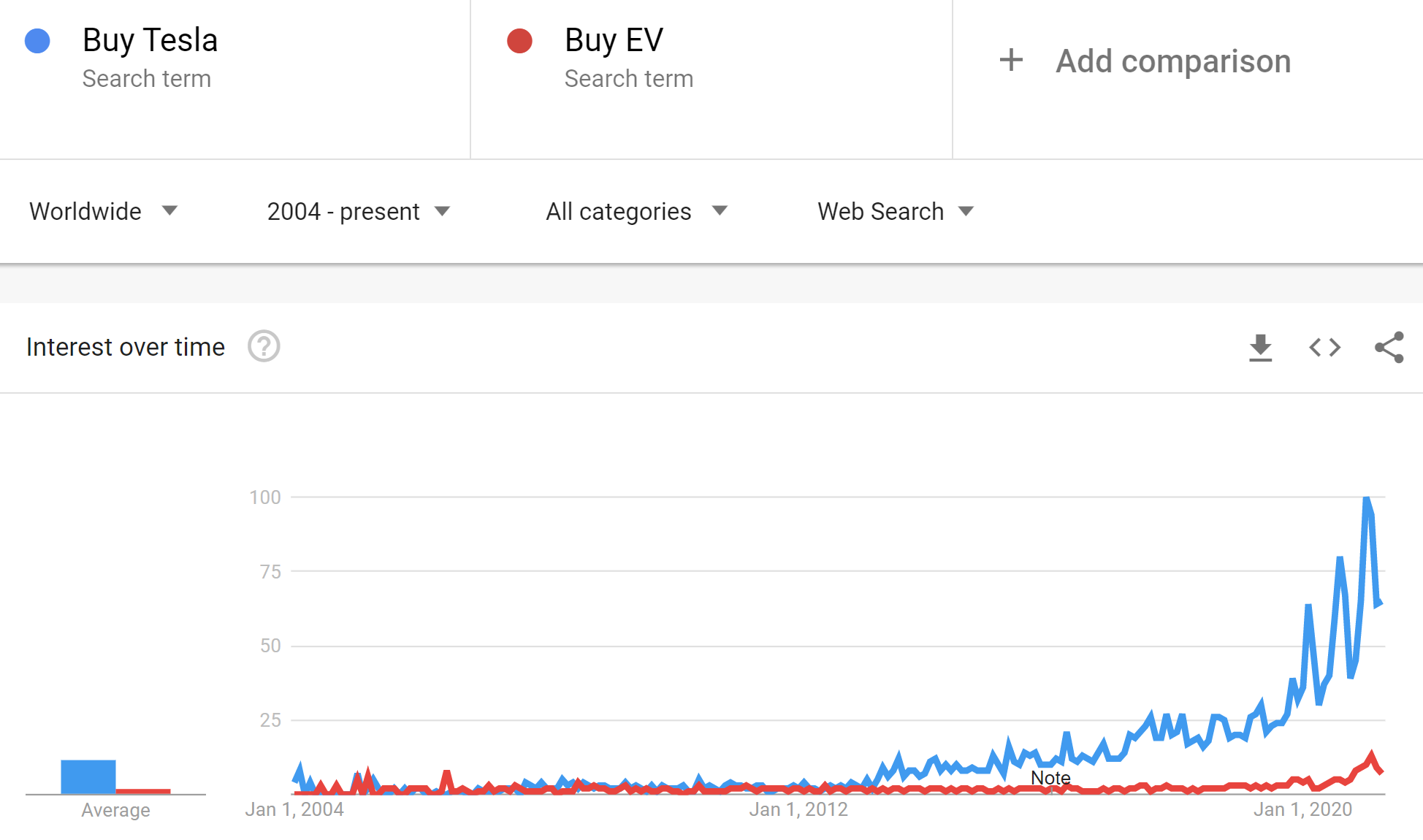

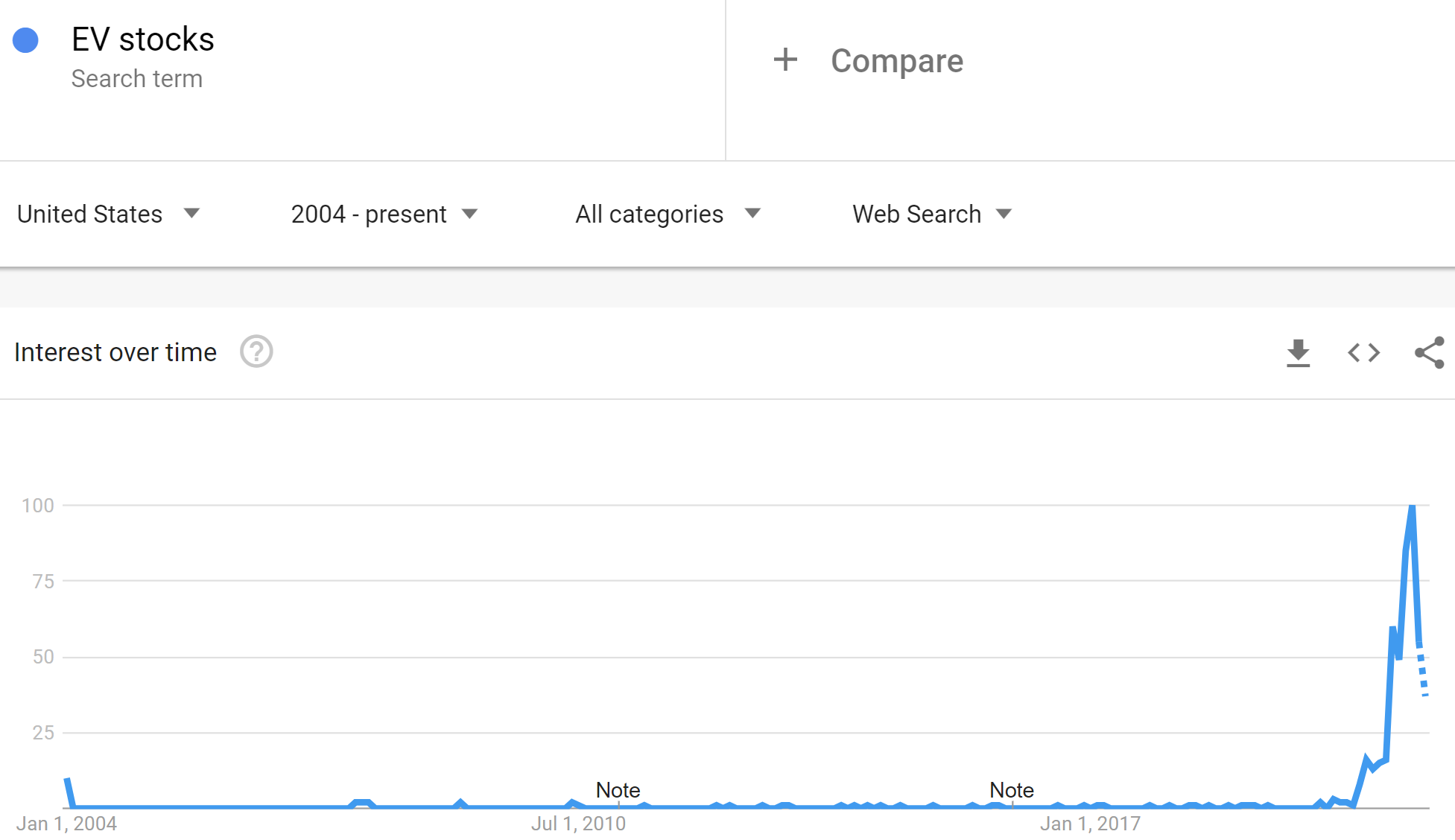

Google search queries on the topic of EVs are mostly related to stock speculation: what EV stock to buy, information about Tesla’s stock price, etc.

You will find that there is an increasing interest in buying electric vehicles as well. At least Teslas. If you compare the search interest for “Tesla” and “EVs”, it looks like consumers are actually more interested in the Tesla brand itself rather than EVs as a product.

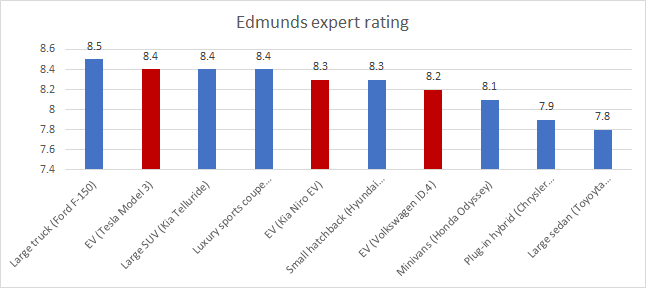

Expert reviews from Edmunds seem to be similar for EVs and ICE vehicles, with no apparent advantage between one and the other.

Typical comments about EVs in consumer reviews emphasize fast acceleration, the convenience of charging overnight, a fun riding experience, range anxiety and significant purchase subsidies:

- “The instant torque and regenerative braking make this thing handle like a supercar.”

- “I plug it in at home at night and wake up with the preset charge I need for the next day. No stopping twice weekly for gas.”

- “This car is so much fun to drive—the instant torque without shifting needs to be experienced.

- “You have to be nuts not to go EV in NJ with all the incentives, and this and the Kona (not quite as practical as the Niro) are the only real choices for value, performance and style.”

- “We, of course, had range anxiety due to our distance from purchasing dealer, but we were pleasantly surprised. Electrify America stations did give us a couple of issues (some were because of operator error), but their support line has a human answer the call within 1-2 minutes, amazing! We made it home with no worries and are already planning the next mini road trip.”

- “The Kona EV is a great and fun car; the downside is that I lost 40 miles on the charge due to the way I drive, I expected to get the 258 miles per charge, but if you drive fast, the battery will only charge to 216 miles for me.”

Anecdotal evidence from Norway suggests that while many households use EVs as secondary vehicles - they don’t drive them as much as ICE vehicles. EVs are used to reduce congestion charges in Oslo or drive in bus lanes, while ICE vehicles are used for longer trips. Norway’s oil consumption has not decreased materially since the country’s wholesale shift to EVs.

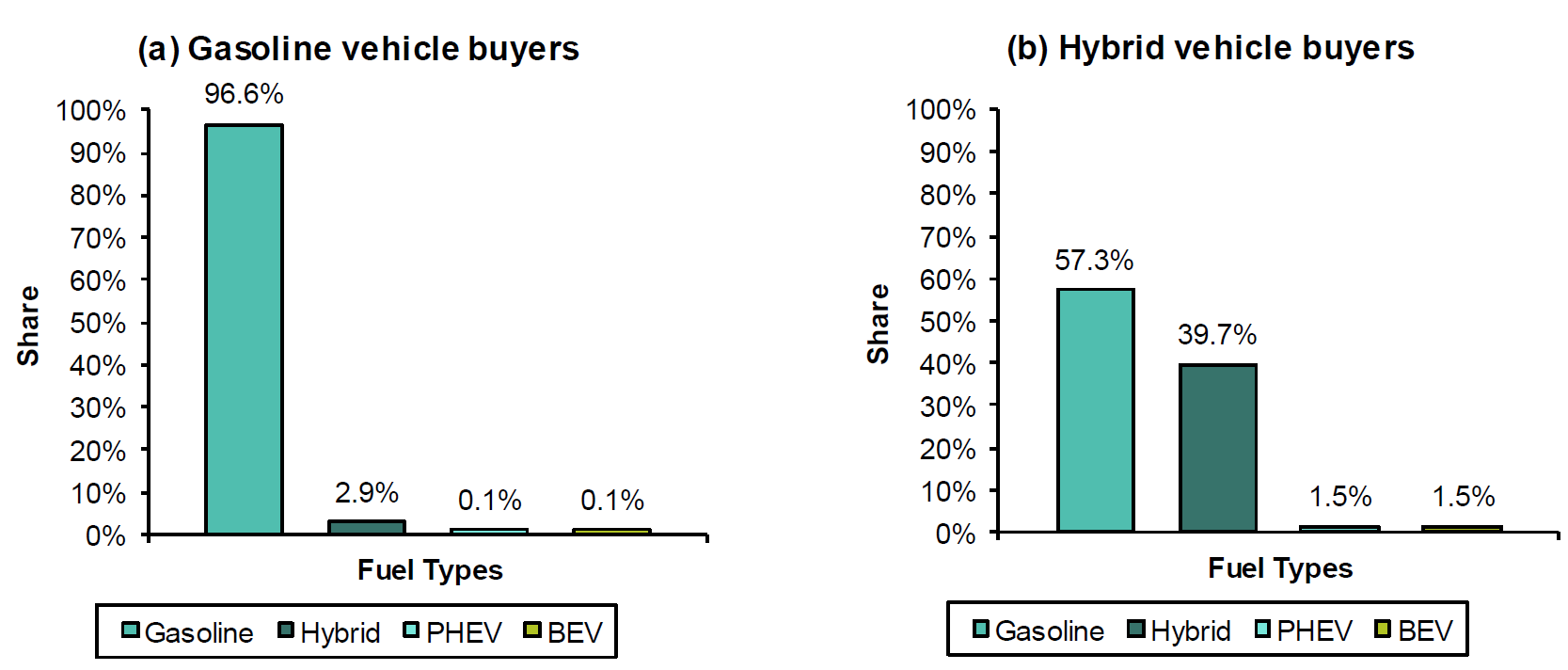

According to research from Xing, Leard and Li in 2019, existing ICE vehicle and hybrid buyers seem to have little interest in shifting to EVs. Fewer than 3.4% of current gasoline vehicle owners had an EV as a second choice. That number may increase, but it’s still relatively low.

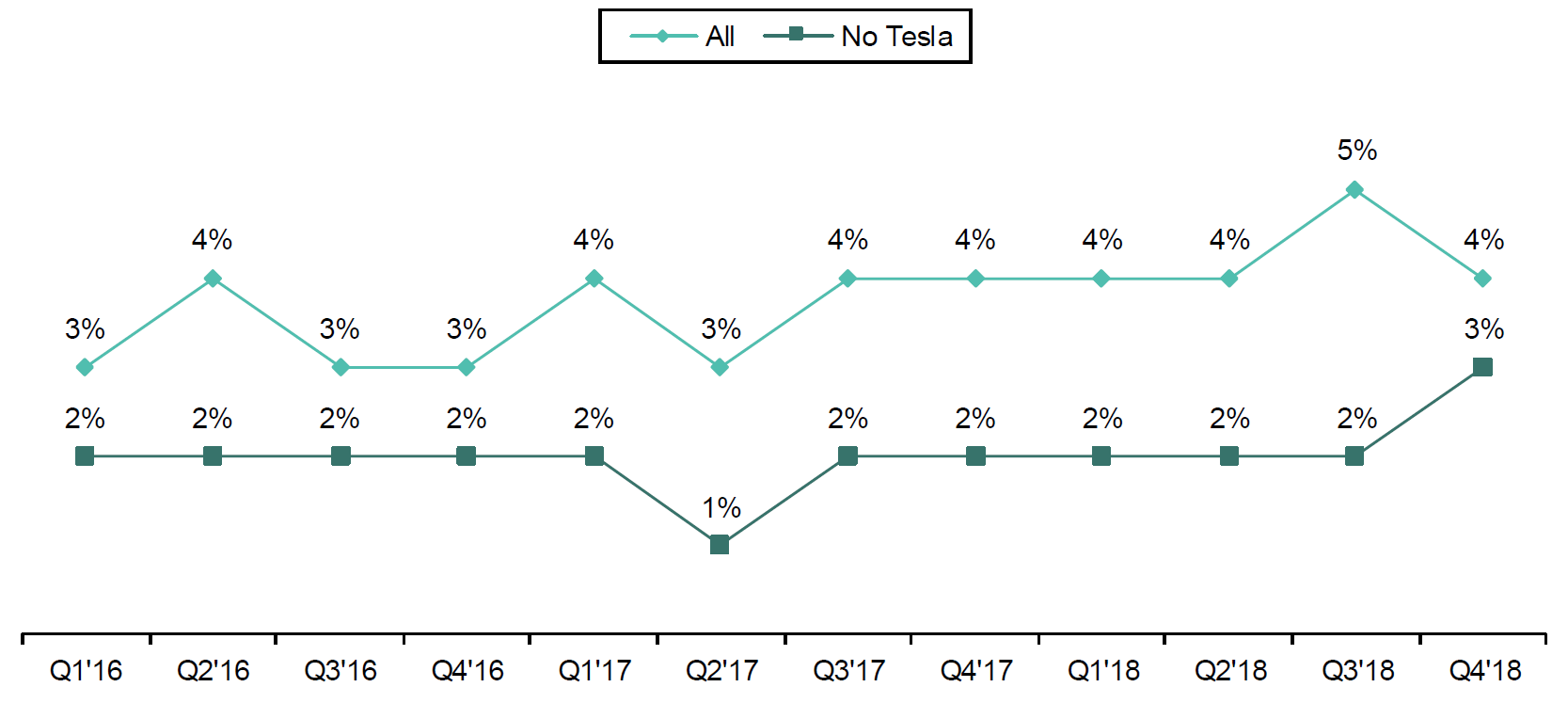

A Cox Automotive survey found that in 2018, around 4% of US car buyers considered an EV. That number had been roughly flat over the two preceding years.

A significant 11% of buyers say they will research EVs as their next purchase but remain uncommitted. Again, what attracts people seems to be driving a sexy Tesla rather than EVs themselves being particularly convenient.

5. Sales performance by region

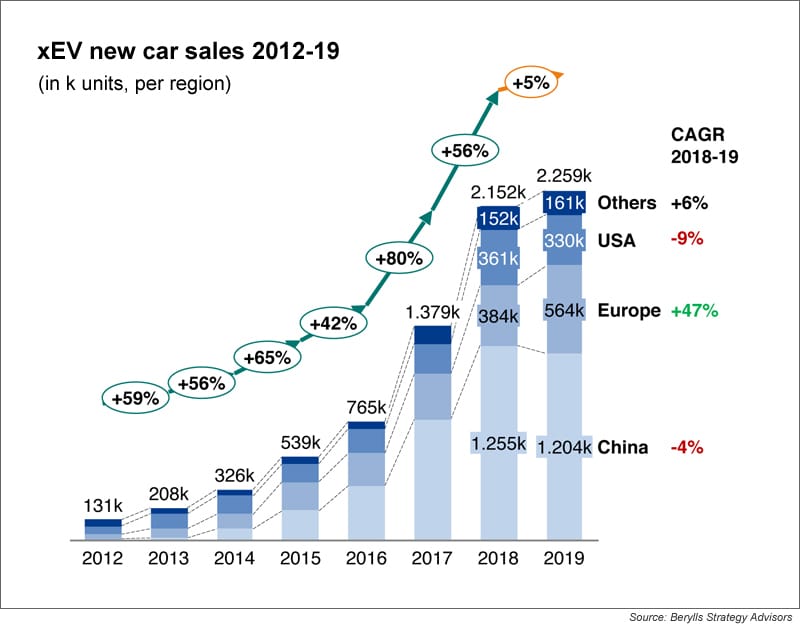

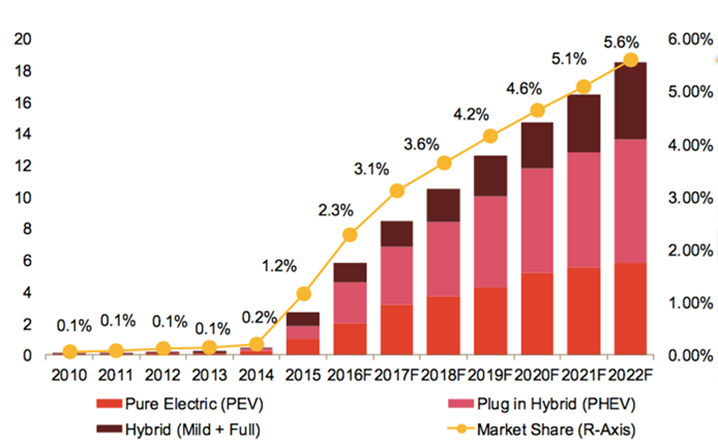

In 2019, total EV sales were about 2.3 million, most of which were in China. That compares to total car sales of about 99 million, giving EVs a market share of 2.4%.

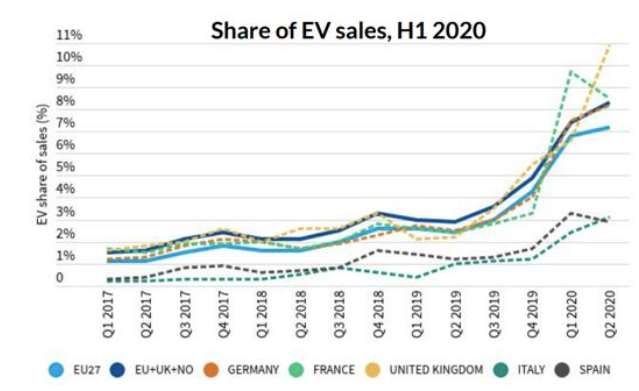

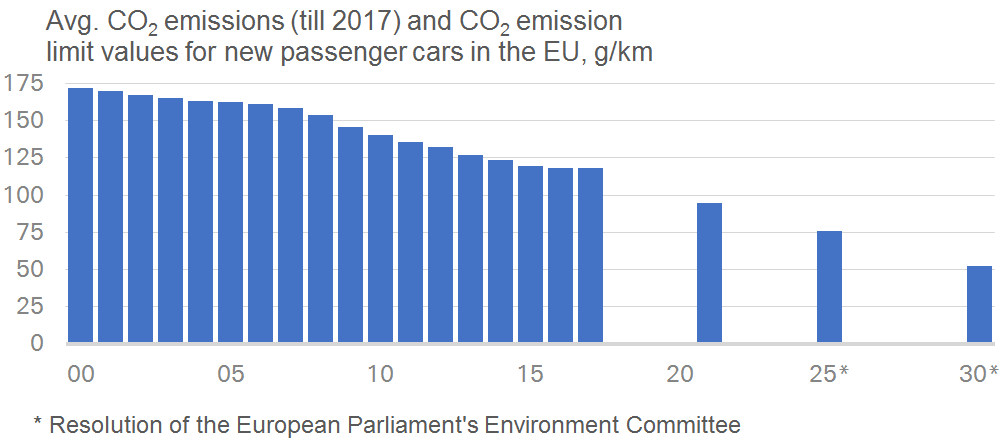

European EV sales boomed in 2020 due to new CO2 emission limits and penalty charges for OEMs who didn’t meet the required targets.

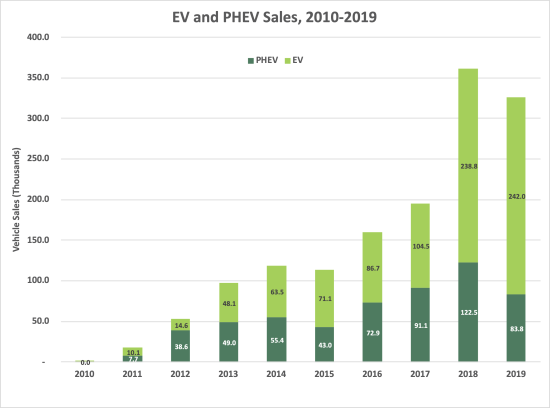

US EV sales increased to 328,000 in 2020, just +4% compared to 2019, giving EVs a market share of 2.3%. That follows a year of strong growth in 2018 when federal subsidies were phased out for several major car brands.

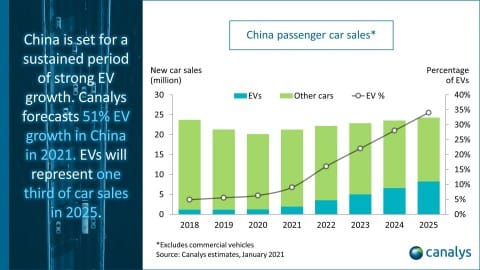

China’s EV sales reached 1.3 million in 2020, roughly 5% of China’s total EV sales and an increase of +8% compared to the prior year. But a large portion of China’s EV demand has come from micro-EVs (= glorified golf carts) and government demand. Some say as much as 70% of EV sales has gone to the government.

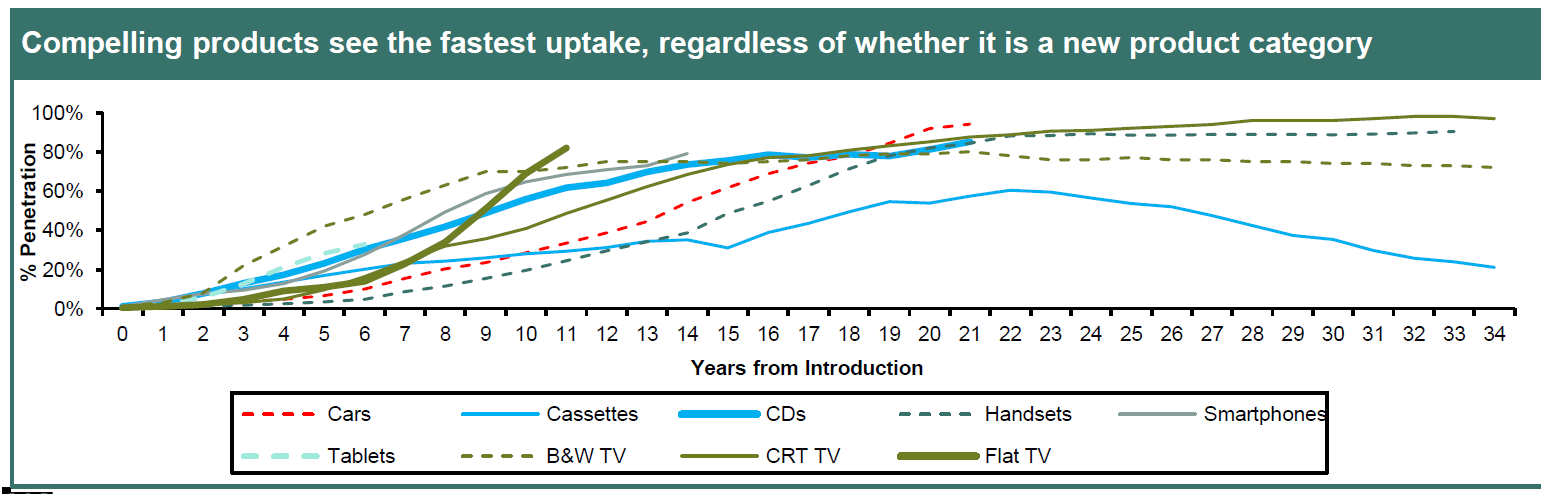

The uptake of electric vehicles as a product has been slow compared to other major inventions. Most major inventions in history reached 70%+ penetration rates within 15-20 years. In the absence of subsidies, growth has been modest. That seems to suggest that the value proposition of EVs is not yet compelling to most consumers.

6. The industry’s reliance on subsidies

Consumers have, however, responded very strongly to government subsidies.

Norway, for example, has offered the following incentives for ICE vehicles:

- No annual road tax

- Maximum 50% of the total fare on ferries

- Parking fees maxed out at 50% of full

- Access to bus lanes

- Company car tax reduction reduced to 40%

- No purchase/import taxes

- Exemption from 25% VAT

- Before 2018, there was also a 50% reduced company car tax, free municipal parking and lower congestion charges in Oslo.

In other words, the subsidies have been massive. A Norwegian woman interviewed by the New York Times in 2018 said:

“If it wasn’t for the subsidies, I guess most people would still choose fuel.”

In the EU, the policy has been focused on adjusting the region’s CO2 emission limits. New average fleet CO2 limits set by the EU in 2020 limited emissions from passenger cars to 99 grams of CO2 per kilometre. If car manufacturers don’t meet the required levels of CO2 emissions, they face a penalty of 95 euros per gram of excess CO2 they emit. That could easily add up to thousands of euros in penalties per ICE vehicle, given that the prior limit in 2018 was 20 grams of CO2 per kilometre higher. These CO2 emission standards will only get tighter as time goes on.

In the US, a federal tax credit for EVs was introduced in 2009 and phased out gradually for the major car manufacturers (Tesla, GM) from 2018 onwards.

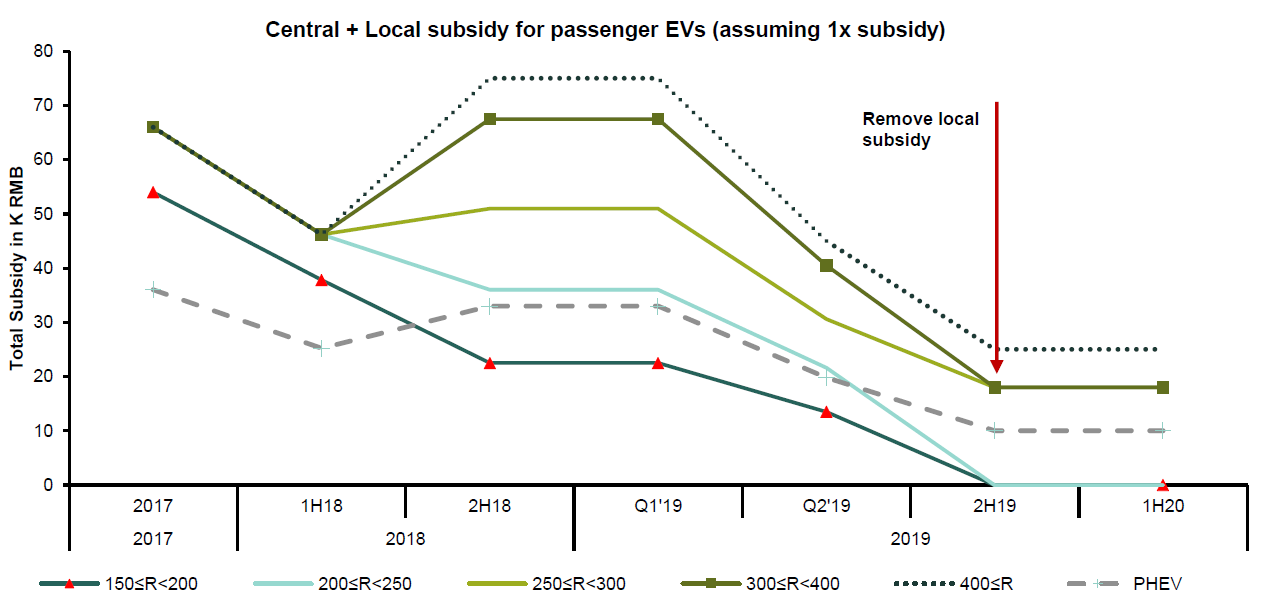

China’s EV subsidies began with carrots around 2014. Following the higher subsidy levels, sales started to skyrocket:

Specifically, China’s EV subsidies have included:

- 10% purchase tax rebate

- Central government subsidies: Range >250km: CNY 44,000

- Local government subsidies: No more than 50% of central grant

- Free license plates or bypassing license plate lotteries

China’s subsidies are now decreasing and could potentially reach zero by 2022. That creates an enormous challenge for the Chinese EV market if the government does indeed follow through on its initial plans of phasing out its subsidies.

With subsidies moving towards zero, the government will instead use supply-side policies to increase the share of EVs as a proportion of total new car sales. These supply-side policies include penalties if a car maker doesn’t produce enough NEVs for every ICE vehicle (“NEV credits”) as well as corporate average fuel consumption credits (CAFC). Therefore, you can expect car companies to sell NEVs at a loss to avoid penalties, pushing down gross margins in the process.

China’s 13th five-year plan announced in 2015 set a sales target of 5 million EVs by the end of 2020. The 14th five-year plan instead aims for NEV sales to constitute 20% of overall new car sales by 2025 - a tall order, to say the least. I can’t see that happening without significant pain for the local OEMs.

The end of EV subsidies in Hong Kong had a very negative effect on Tesla’s sales in the city, with sales dropping to almost zero:

When Denmark out its EV subsidies in 2016, sales fell from 5,000 in 2015 to 700 in 2017, a drop of around -86%.

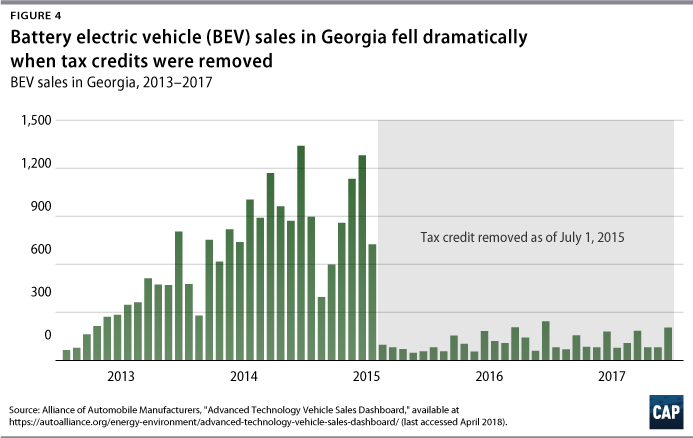

When the US state of Georgia phased out its EV tax credits, sales also fell approximately -90%:

In other words, in the next two decades, at the very least, the EV market will be highly reliant on changes to subsidy policies. That means that EV sales are likely to increase in Europe and decrease in China. And producers of conventional vehicles in both Europe and China are likely to suffer from higher penalties and production requirements.

7. Parts of an electric vehicle

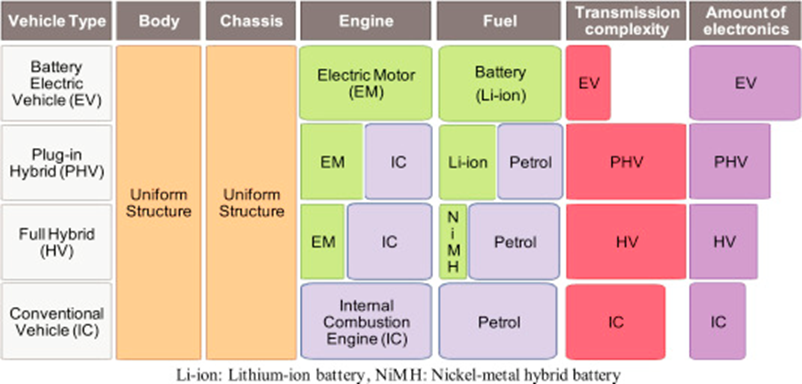

The shift from conventional vehicles to electric vehicles will lead to a shift in demand in auto electronics. The electronics content for hybrids might be even higher than that of typical EVs. The EV drivetrain is simpler. The body and chassis will look largely the same.

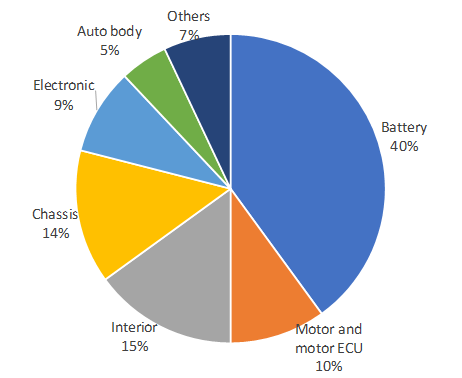

The battery pack represents the major cost of building an EV. That makes their customers (auto OEMs) price-sensitive.

Giving the shift to a higher electronics content, I suspect that auto-related software and electronics will end up as the big winners in this shift.

8. The EV stock universe

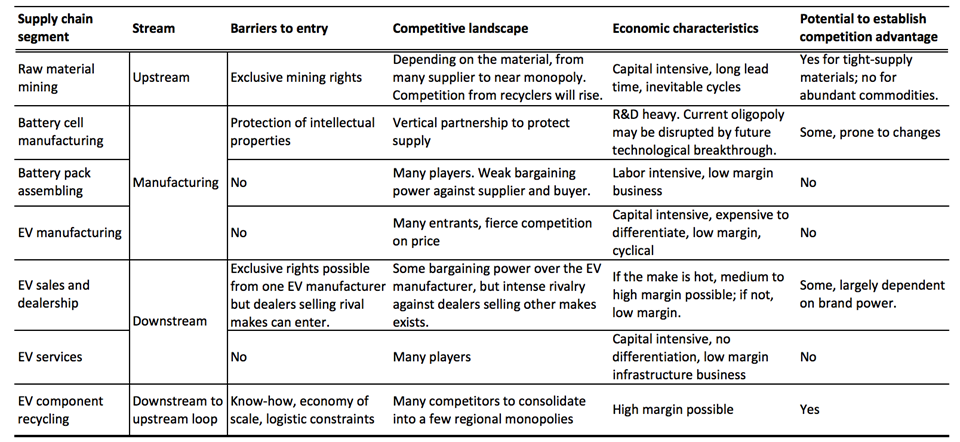

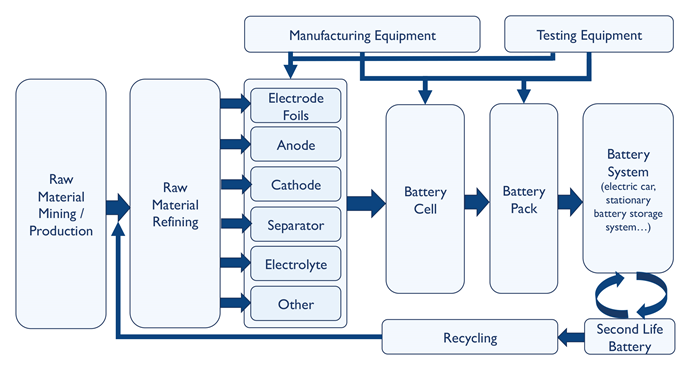

The main areas of the EV supply chain are raw materials, battery cell manufacturing, battery pack assembly, EV manufacturing, EV sales and dealerships, EV repairs and component recycling.

Here is a specific flow chart for the EV battery industry:

Which part of the supply chain holds the bargaining power?

- Raw material mining: Mining is a commodity industry. Some resources are in truly scarce supply, however, including cobalt and rare earths.

- Battery makers: Battery packs represent a major portion of the total cost of buying an EV, so battery pack producers are likely to face pressure to reduce overall costs.

- Auto OEMs: Competition is cutthroat between EV OEMs and traditional OEMs, with little product differentiation. China has 400+ EV OEMs alone and 100+ actively producing vehicles.

- Dealerships: Tesla has done away with dealerships entirely. But traditional auto OEMs are likely to use the same dealership networks as before.

- Electronics suppliers: The products within the supply chain that are unique include power semiconductors and assisted driving system software. It will be hard to replace say Infineon power chips or Waymo autonomous driving software.

- Recycling: High margins could be possible in EV component recycling, due to the licensing requirements that are typically imposed for companies dealing with hazardous materials.

In summary, the auto industry is competitive. There may be examples of pick-and-shovel stocks that benefit from the industry's growth without much competition or the need to make risky investments, but they are few and far between. I believe the sweet spot is in software and electronics.

9. Speculative sentiment

Buzzwords such as “3D Printing”, “AI”, “machine learning”, “cyberspace”, etc. tend to go along with every major speculative bubble. In the case of electric vehicles, speculators now refer to them as “EVs”, and that has become the buzzword on stock related messaging platforms. The attention to EV stocks began in early 2020 following the pandemic and has now reached unprecedented levels.

Among the most traded stocks among Fidelity customers, you will find several EV-related stocks, including Tesla and NIO.

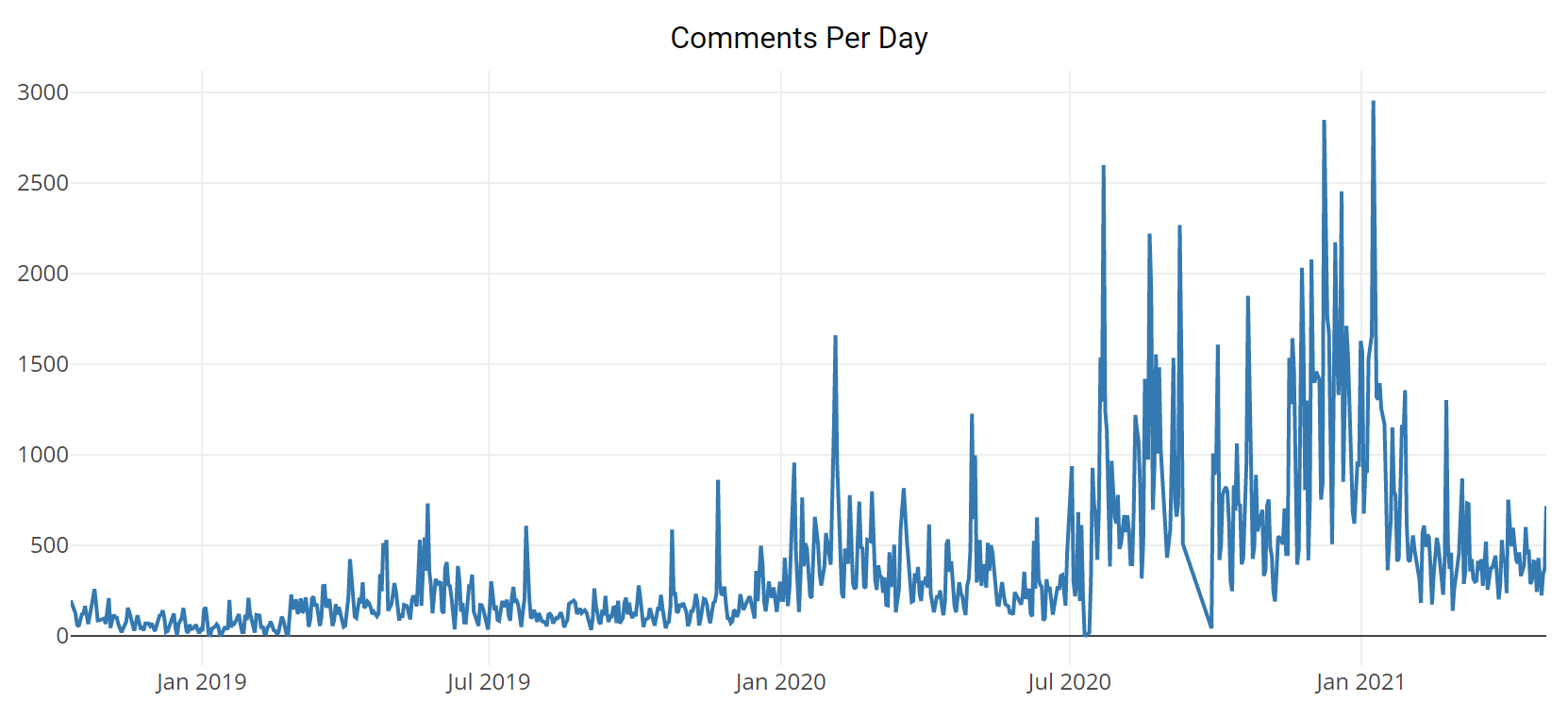

The number of comments per day on the r/TeslaInvestorsClub subreddit peaked in December 2020 after rising around 10x compared to 2019:

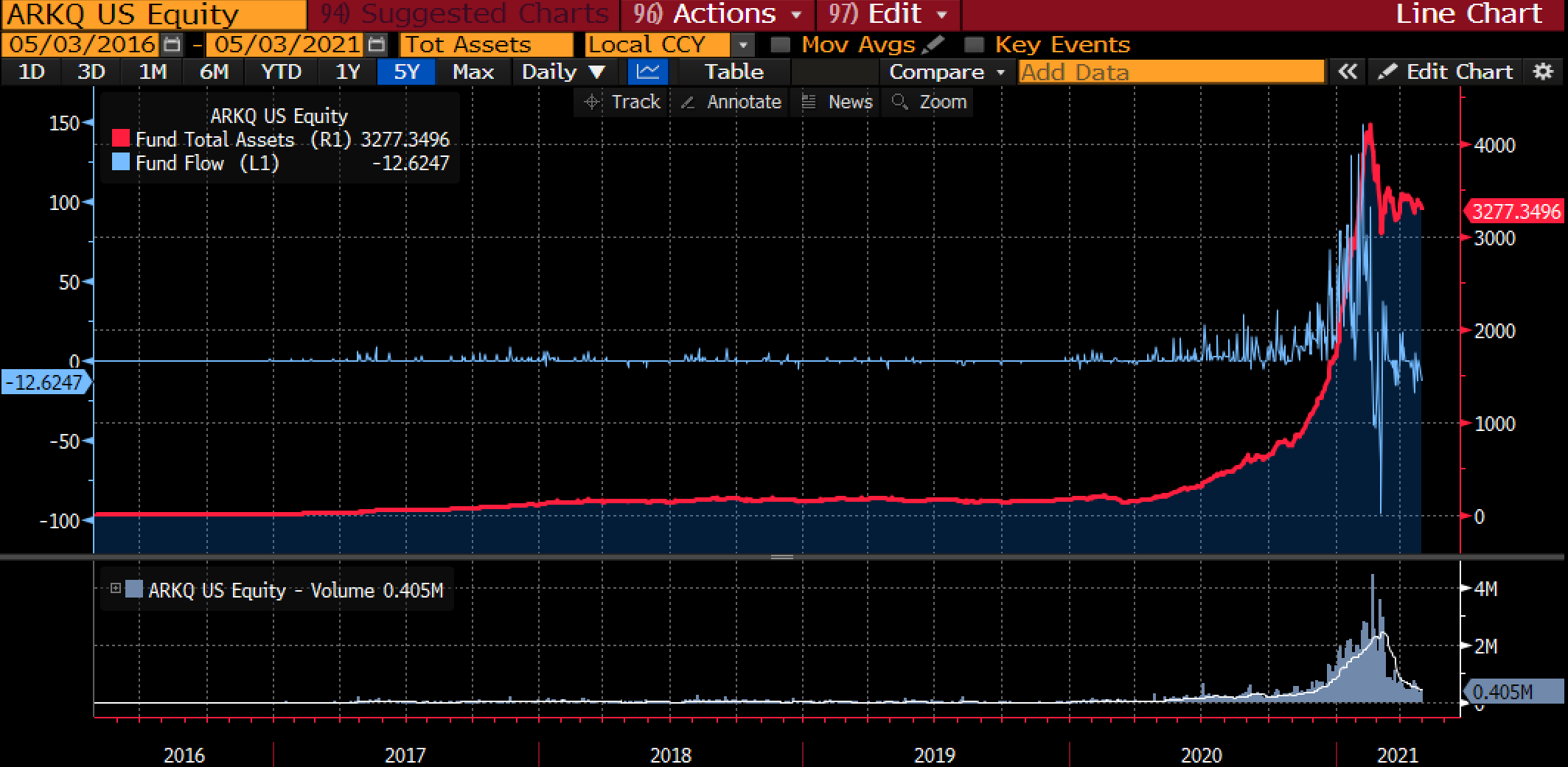

ARK Invstment’s Autonomous Technology & Robotics ETF saw its total assets and volumes peak in February 2021. The same can be observed for several related ETFs, including the Global X Autonomous & Electric Vehicle ETF (DRIV US), Global X China Electric Vehicle ETF (2845 HK) and iShares Electric Vehicle ETF (ECAR LN).

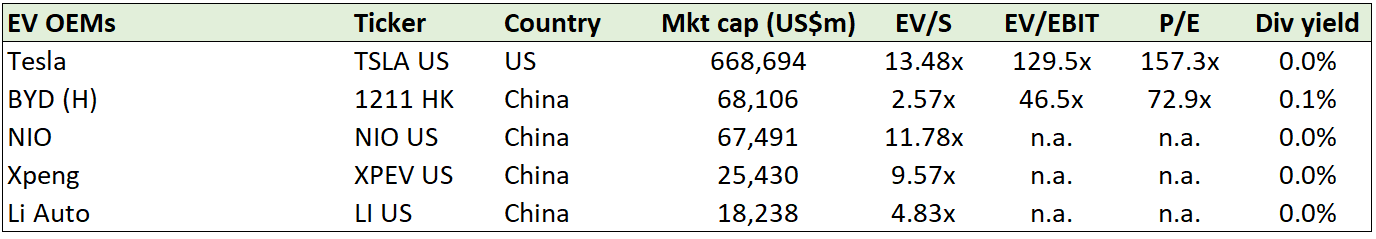

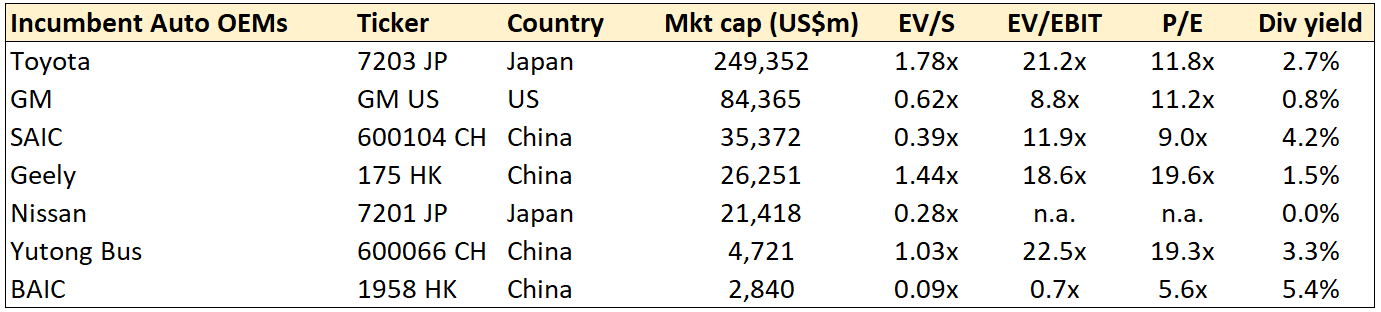

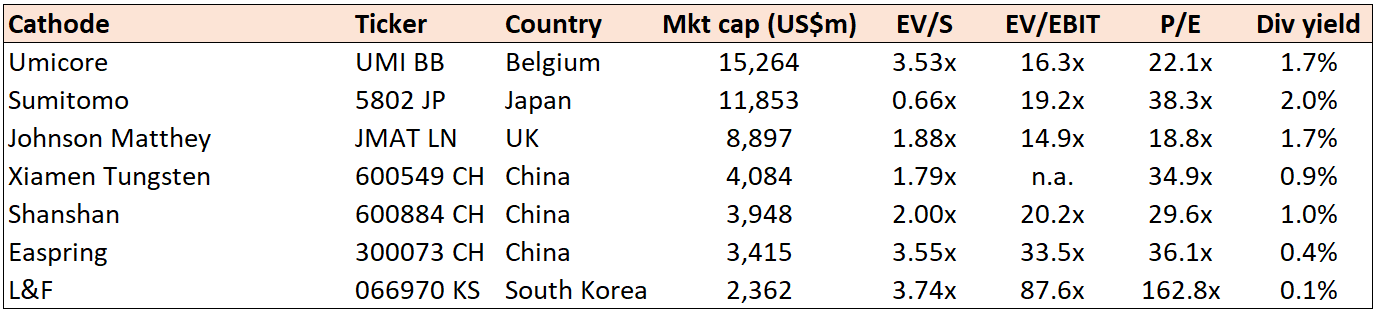

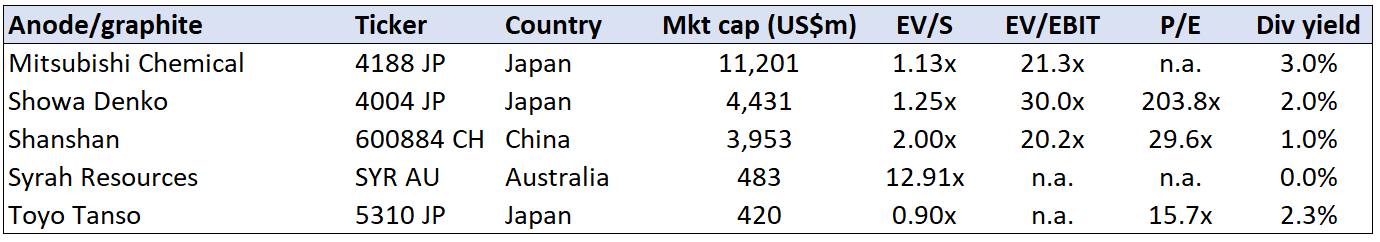

10. Valuation multiples

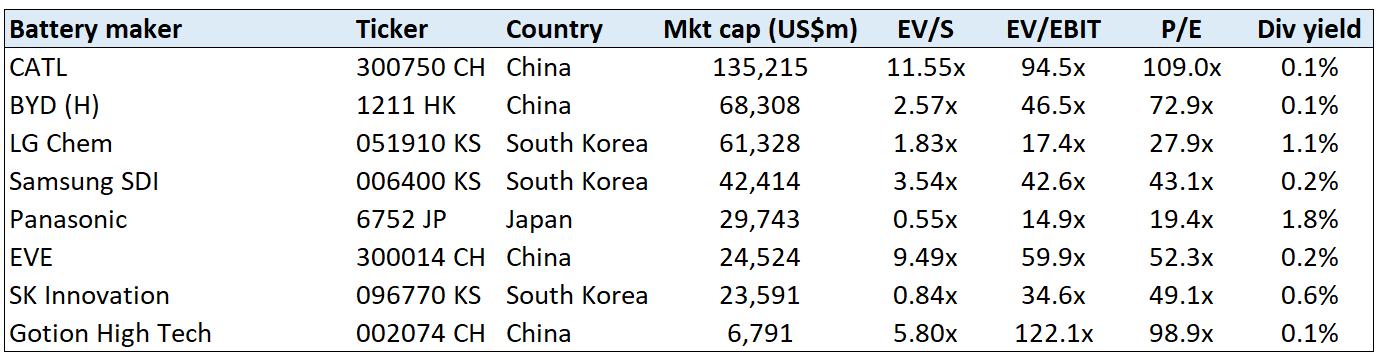

Within the battery segment, the clear market leaders are Samsung SDI and LG Chem since they are both at the top of Navigant Research’s energy storage quadrants. CATL is starting to catch up at #5 globally in accumulated patents since 2015. Whether those patents will lead to marketable products is another question. The valuation multiples are high across the entire sector, except for a few exceptions such as Panasonic and SK Innovation. Margins in the battery industry have traditionally been in the mid-single digits. It is not yet clear whether EV battery margins will be higher than for smartphone batteries or appliance batteries.

Tesla is the brand name in the EV industry that has gained significant customer loyalty. Competition is now heating up with OEMs offering similar product offerings. Tesla still holds an advantage in its well-developed charging infrastructure in the United States. But valuation multiples for EV OEMs are high across the board.

Be careful of traditional OEMs in the next few years as they will hurt from their EU and Chinese exposures. CO2 and CAFC/NEVC penalties will continue to hurt them. Supply-side policies cause losses, and such losses will be distributed across the government, auto manufacturers and customers. OEMs will be forced to sell EVs at low gross margins - even at a loss - to avoid penalties in the near term.

Materials technology company Umicore should be on your radar given its dominance in the sector. That said, neither of the below materials stocks enjoys high margins or high ROEs.

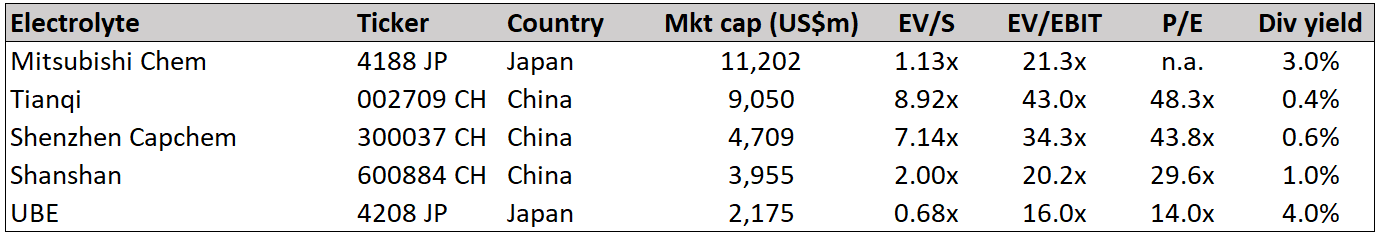

Mitsubishi Chemicals has a broad portfolio of chemical products. Showa Denko is involved in both petrochemicals and EV anode materials. Syrah Resources is an Australian miner with exposure to graphite, vanadium, mineral sands, copper, coal and uranium.

Guangzhou Tinci Materials and Shenzhen Capchem both seem to be relatively pure-play bets on electrolyte materials. In contrast, Shanshan, Mitsubishi Chemical have a presence across cathodes, anodes and electrolyte materials.

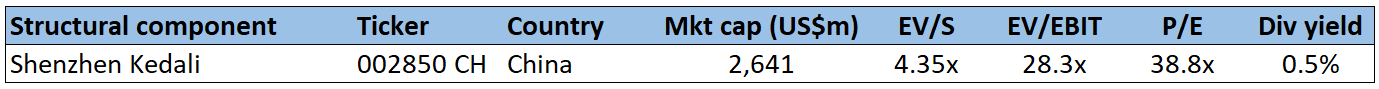

Shenzhen Kedali produces metal hardware products for lithium batteries, including for the energy, auto, solar industries.

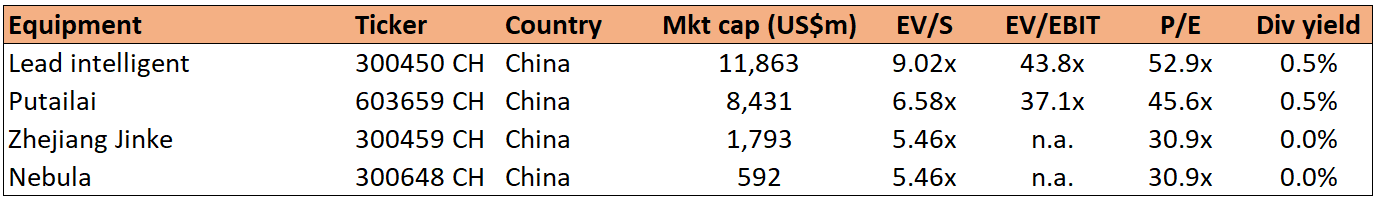

Wuxi Lead Intelligent produces electronic capacitors and lithium battery equipment, especially for pouch batteries. Putailai produces anode materials and coating membranes. Zhejiang Jinke’s chemical business is a small portion of the total. Nebula manufactures inverters and battery testing equipment.

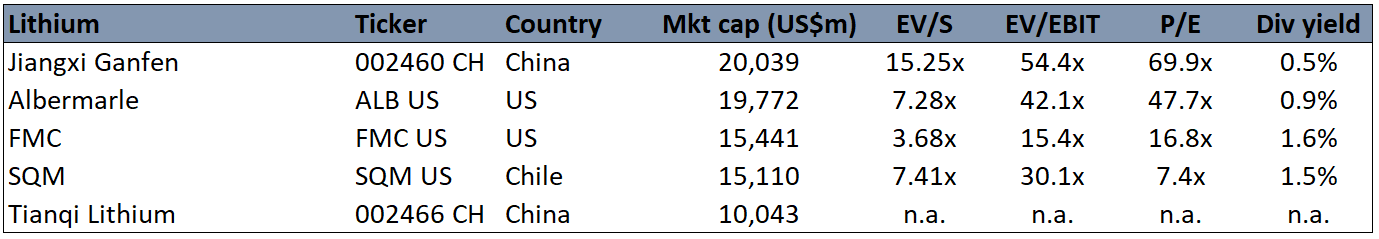

Major lithium stocks such as SQM, Albermarle etc., are trading at record prices. As supply tends to expand to meet demand, I suggest keeping away until we get another cyclical trough when supply eventually meets demand again.

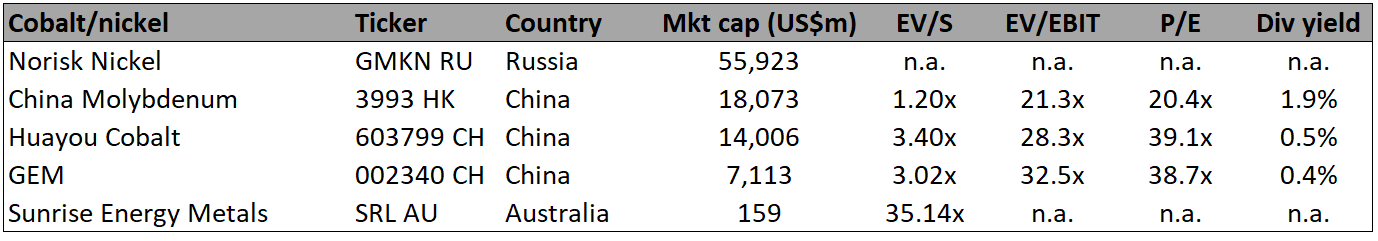

Nickel and cobalt are both key raw materials in the production of cathodes in batteries. Cobalt is a truly scarce resource, and a pure-play bet such as Huayou could be of interest for that reason.

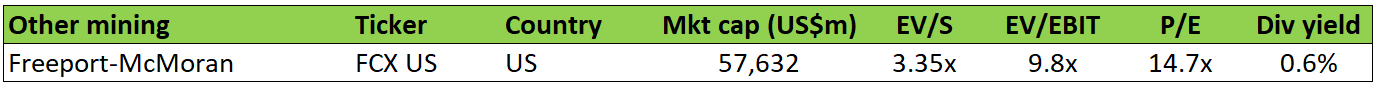

Miner Freeport-McMoran does not have major EV exposure. The stock is also trading at a cyclical high point after its recent rally.

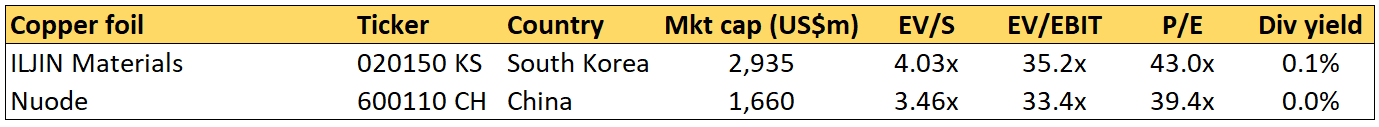

The copper foil used in batteries is produced by both Iljin Group’s listed subsidiary Iljin Materials and Shenzhen-based Nuode Investment Co. Neither of them has large exposures to the EV industries, and return on capital has historically been weak.

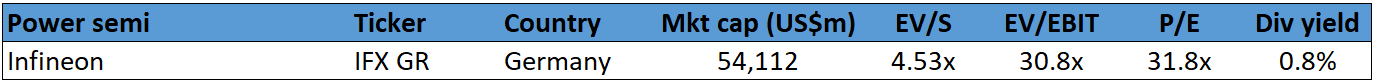

Semiconductor company Infineon has roughly 40% exposure to automotive power-related chips. Though the EV exposure is only around 6%, this proportion is likely to grow over the coming decades. The valuation multiple is high but comparable to other blue-chip semiconductor stocks.

11. Related investment opportunities

Electric vehicles are likely to take market share slowly as energy densities improve, battery prices drop and charging speeds go up. Don’t expect a wholesale shift towards EVs until the value proposition becomes clear: when they reach cost parity with ICE vehicles and the charging issue is solved.

However, I believe the EV sector is in the middle of a speculative bubble, with the trend of greater EV adoption well recognised at this point. I see most opportunities on the short-side, in particular:

- Chinese EV OEM concept stocks such as Li Auto, Xpeng and potentially NIO. Related catalysts will be China potentially pulling the plug on all EV subsidies from 2022 (at the earliest).

- European or Chinese auto OEMs are exposed to higher penalty charges and might be forced to sell EVs at low gross margins. Some of the Chinese auto stocks have risen significantly over the past year, despite minimal exposure to EVs.

This is not the time to look for bargains in the sector. If anything, investors should brace for impact.

If you would like to support me and get 20x high-quality deep-dives per year, thematic reports and other reports, try out the Asian Century Stocks subscription service - for the price of a few weekly cappuccinos.