Table of Contents

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

- Erin Meyer’s book The Culture Map tries to deconstruct cultures into eight component parts across how we communicate, make decisions and think.

- According to her research, Asian cultures tend to be more hierarchical, more subtle in their communication and more flexible with regard to schedules. Meanwhile, Northern European cultures are at the opposite extreme, being more egalitarian, explicit in their communication and even confrontational.

- Potential implications for investors include how we interpret messages from individuals from each culture, predicting how well an individual will do in a particular cultural environment and the comparative advantages of organisations from different cultures.

Our friends at China Charts recently recommended the book The Culture Map by Erin Meyer. I spent part of my vacation reading through it and found it chock-full with insights.

It helps us understand how people from different cultures think and behave. And while the material is targeted towards the MBA students Erin Meyer teaches at INSEAD, investors should also find the material useful.

Interpreting messages in light of our cultural biases helps us decode messages. It can help us predict people’s behaviours. And perhaps even help us identify companies' competitive advantages if they’re rooted in culture.

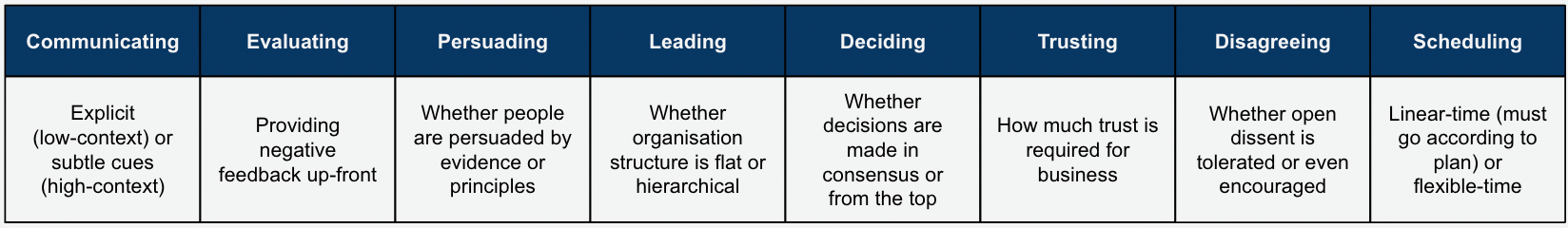

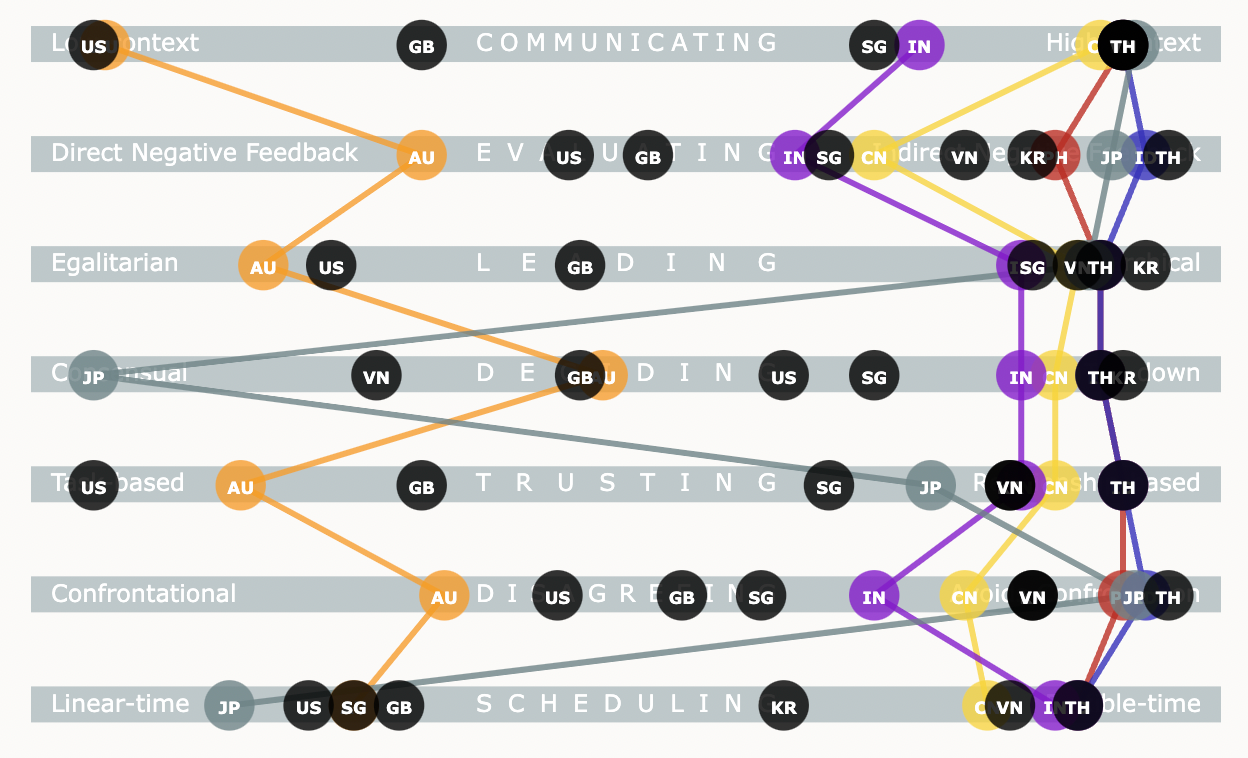

Erin Meyer looked at her survey data and concluded that cultural differences were rooted in eight key dimensions:

In her view, these eight dimensions largely explain the differences in how people behave.

For example, the communicating, evaluating, and disagreeing dimensions have to do with how direct we are in our communication. The leading, deciding and trust dimensions have to do with company hierarchies. Persuading and scheduling have to do with people’s mindsets.

There might be overlaps between the categories, but let’s leave that aside for now. And also, be aware that these are generalisations and that individual differences can be far greater than those predicted by culture.

Table of contents

1. Communicating: explicit or not

2. Evaluating: negative feedback

3. Persuading: fact- or principle-based

4. Leading: flat or hierarchical

5. Deciding: who decides

6. Trusting: the need for relationships

7. Disagreeing: embracing confrontation

8. Scheduling: following the timeline

9. Conclusion1. Communicating: explicit or not

The first dimension Meyer emphasise is how explicit the communication is between two individuals.

For example, Americans are famously explicit. A rule for public speakers in America is apparently to “tell the audience what you’re going to tell them., then tell them, and finally tell them what you’ve told them”. Textbooks are designed similarly, not to economise on words but rather to make messages as clear as possible.

Meyer calls such cultures low-context since not much context is needed to understand what the other person is trying to say. People from such cultures will generally tell you explicitly what they want to get across.

At the other end of the spectrum, you’ll find countries in East Asia such as China, Japan, Korea and Indonesia. Here the communication style tends to be more subtle. A long shared history has created assumptions of what different behaviours mean. Subtle cues will help the listener understand the messages. That listener must try hard to “read the air” to understand. Because there’s a long shared history of what words and behaviours might mean, Meyer calls these cultures high-context cultures.

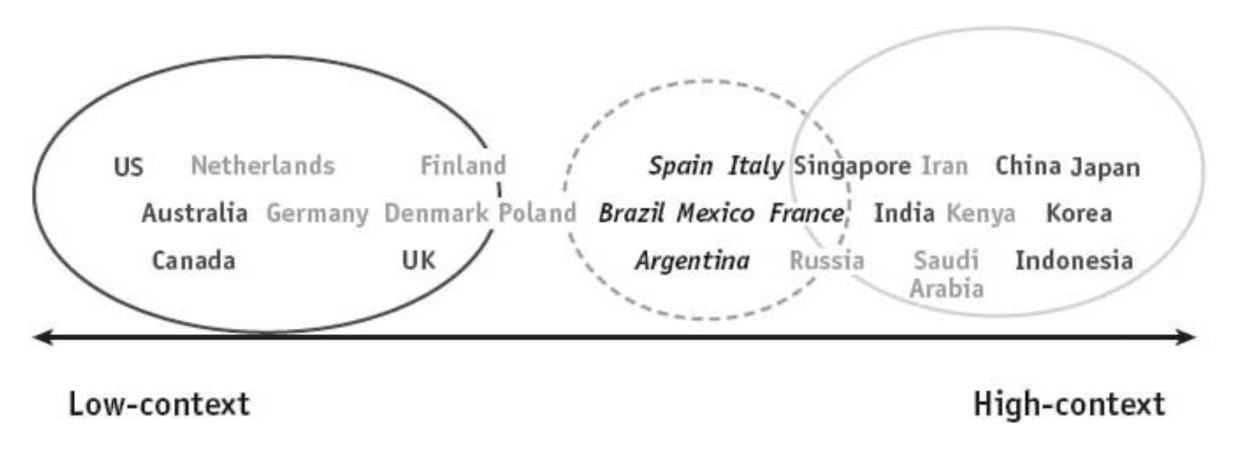

Here is a chart showing where countries belong in this dimension. Europe belongs to the low-context, explicit part of the spectrum. And East Asia - China, Japan, Korea, Indonesia - belong to cultures where communication is more subtle.

Why does this matter? Because the same message can be interpreted differently by people from each of these extremes.

- For example, the direct Dutch tend to think that you are not trustworthy if you don’t say it straight.

- But a person from Indonesia will think that if you’re too direct, or too explicit in your communication, you’re treating them like children. That spelling out a task in great detail is a sign that you don’t trust the recipient to figure out the solution on his or her own.

The takeaway is obvious. If you’re meeting with people from East Asian cultures, you’ll generally need to exert effort to understand the subtle cues provided to you. You’ll need to listen more and speak less. And ask the speaker to clarify if you’re not sure you’ve fully understood.

So if you’re meeting with people from East Asian cultures, you’ll need to exert effort to understand the subtle cues provided to you. Listen more and speak less. And ask them to clarify if you’re unsure if you’ve fully understood.

2. Evaluating: negative feedback

Another key differentiator between cultures is the willingness to provide negative feedback.

Just because a person is explicit in his or her communication doesn’t mean that the person is willing to provide criticism. Americans, for example, are often direct and explicit in their communication but still cautious in providing criticism.

Instead, Americans often provide positive feedback before touching on the negatives. They will also generally try to downplay negative criticisms with qualifiers such as “kind of”, “sort of”, “a little”, “a bit”, “maybe”, or “slightly”.

An American will probably find the negative feedback from individuals from the Netherlands, Germany and Russia overly harsh. Meyer argues that people from these countries learn from an early age, to be honest and give messages straight.

From their perspective, Americans are not being truthful enough. Their feedback might be seen as somewhat fake:

“With Americans, the grid is different. Excellent is used all the time. Okay seems to mean not okay.”

Qualifiers used by people from the Netherlands, Germany, and Russia are more often words such as “absolutely”, “totally”, “strongly”, etc. They generally don’t beat around the bush.

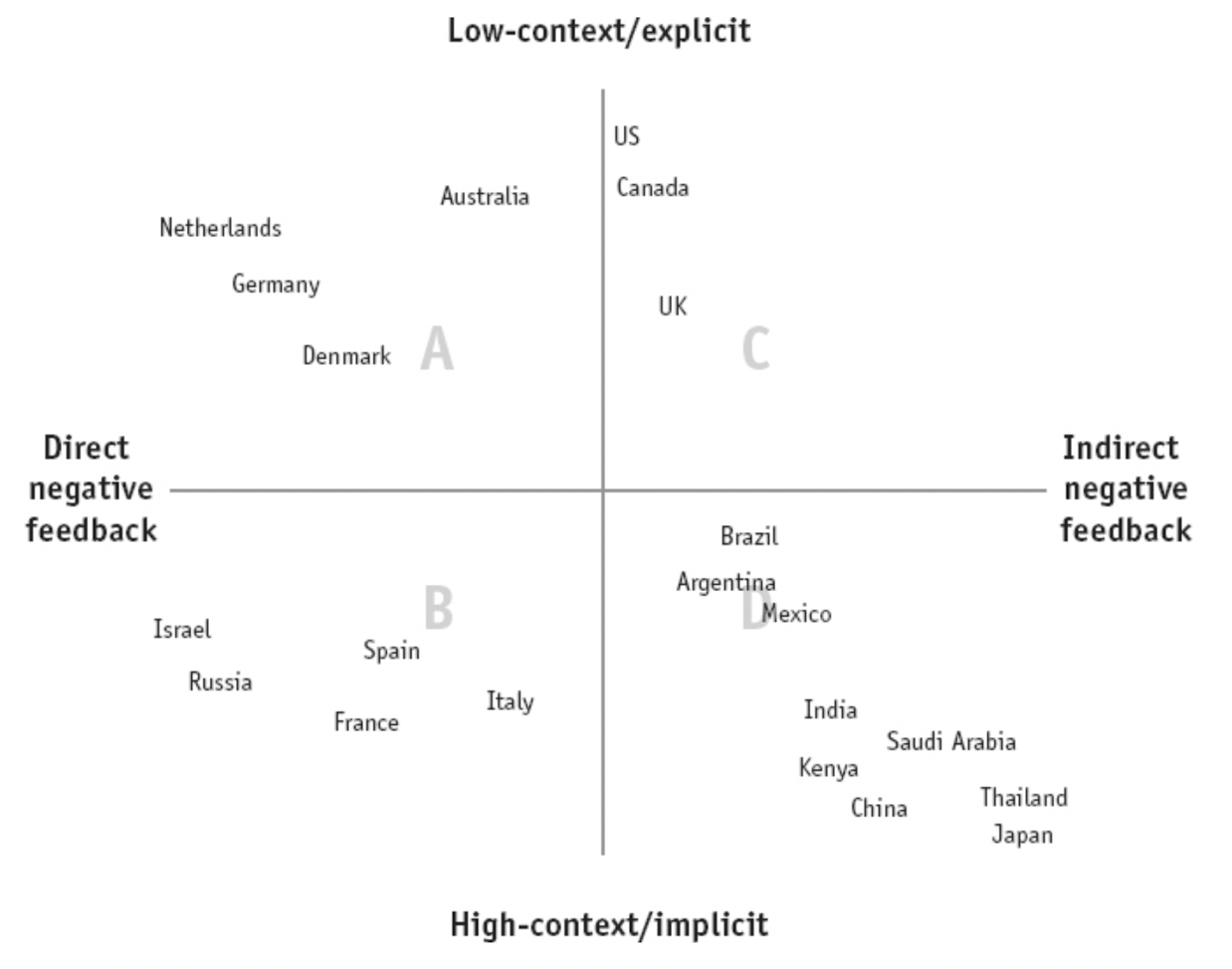

Here is a chart from Meyer’s book showing how each culture can be mapped along the explicit/negative feedback dimensions. You can tell that the Anglo-Saxon countries tend to be more cautious in providing direct negative feedback, while Northern Europeans tend to be more frank.

East Asia stands out on the bottom-right-hand side of the chart. It seems like they generally use subtle cues to communicate, including when it comes to indirect negative feedback.

But Meyer makes a distinction here. She argues that within the family, they may be frank with criticism, especially with their children. But when it comes to colleagues and those in higher ranks, they learn never to criticise openly. Be extra careful providing negative feedback to a person in front of his or her group. That would be a cardinal sin.

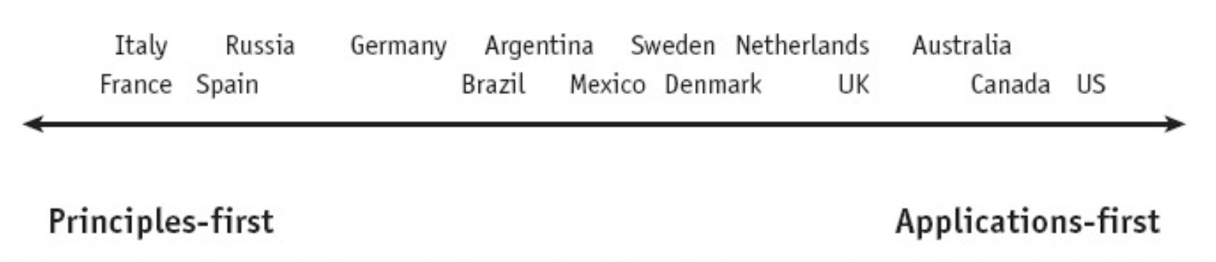

3. Persuading: fact- or principle-based

Erin Meyer makes the point that the way to get persuaded by somebody differs greatly from country to country.

In America, people will be persuaded by evidence. They want to see the practical application first before drawing any conclusions.

Anglo-Saxon school systems are apparently centred around this idea. And you also see it in the common law legal system, in which a judgment sets a precedent for future cases.

In Germany and Latin countries, on the other hand, people will be more persuaded by theoretical frameworks that are then applied to practical situation. Meyer calls this principles-first reasoning.

In countries with principles-first reasoning, the structure of an argument often follows the following outline:

- Thesis: Lay out the argument

- Anti-thesis: a counter-argument

- Synthesis: Contrast the two arguments and finally reach a conclusion

Countries belonging to the principles-first part of the line will find an argument this way. Only when a counter-argument has been provided do they feel confident that the thinking is robust?

In applications-first countries like America, you’ll want to get to the point quickly. Provide a real-life story of success and then induce general lessons from it — exactly how Harvard’s case studies are structured.

Meyer makes a final distinction. She argues that Asians tend to have a more holistic mindset, giving more attention to the background and context of a particular issue. So when it comes to persuading someone from the Eastern part of the globe, she argues you’ll want to start from a macro point of view. Explain how everything fits together, and only then deal with the issue more granularly.

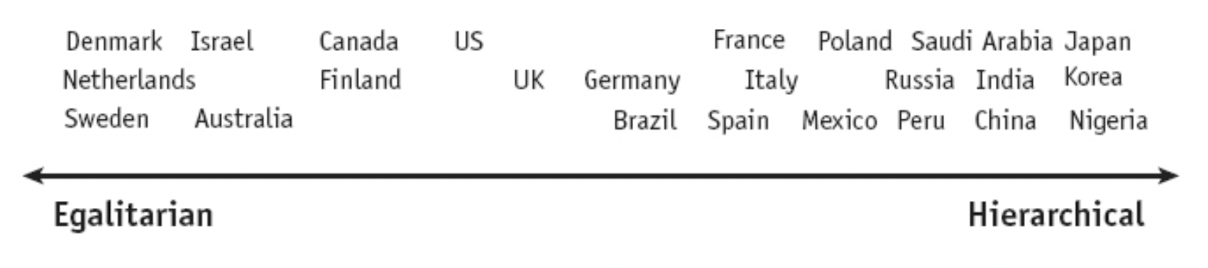

4. Leading: flat or hierarchical

We now come to the question of hierarchy. Some societies are more hierarchical than others, which matters in how we communicate and behave.

The definition of egalitarian cultures is that leaders at the top are treated the same way as those lower down in the organisation. Leaders push power down and then try to step out of the way. They work by setting objectives and then rallying the team around those objectives.

In hierarchical cultures, however, all problems are pushed up, and it’s up to one leader to decide. Organisation charts will be important in such cultures, with a clear sense of who belongs where in the hierarchy.

A lot of miscommunication can happen to people who work in teams from across cultures. Someone from a hierarchical culture will see an egalitarian leader as weak and ineffective. Someone from an egalitarian culture will find a forceful leader overbearing and disrespectful. The working styles of teams from the two extremes will be dramatically different.

Meyer speculates that cultures have been formed by political systems in the past. That Latin cultures might have been influenced by the famously hierarchical Roman empire. That Northern European societies have been known to be egalitarian all the way back to the Viking era. And that East Asian cultures have been influenced by Confucian philosophy, where you’re told to respect the elderly and others higher up in the hierarchy.

Most Asian countries belong to the hierarchical part of the timeline, while Northern Europe tends to be more egalitarian.

On a practical level, Meyer argues that in the hierarchical societies in East Asia, you’ll want to pay respect to people higher up in the hierarchy. Address emails to people at the right level; in meetings, you should greet the seniors first, etc. But leaders in the more Confucian countries are also expected to protect and care for those under them. So even in highly hierarchical societies, there is still a give-and-take that creates a balance.

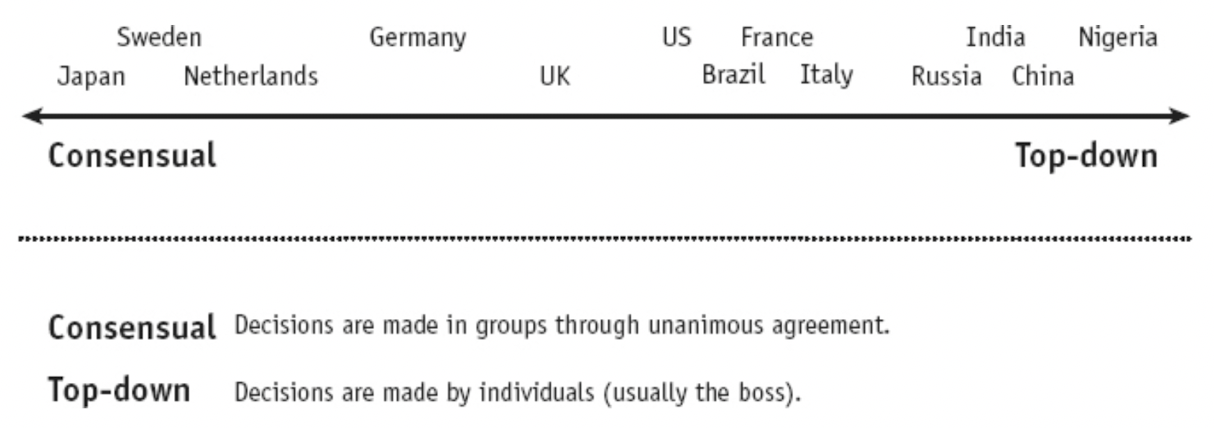

5. Deciding: who decides

Dimension number five is about decision-making. Who within the organisation actually makes the final call?

Meyer argues that the hierarchy doesn’t always explain who makes the decision. In some countries, such as Germany, organisations tend to be hierarchical, with great respect paid to those higher up. But decisions are still made in consensus.

But usually, there is a correlation between how hierarchical an organisation is and whether the person at the top makes the final decisions. America is famously top-down, with leaders deciding on strategy alone. Meyer thinks that such a setup helps organisations make decisions fast. But she also thinks that it puts pressure on the leader to have the relevant skills necessary to deal with all the problems that land on his or her desk.

The other option is consensus decisions, which sounds great in practice but also introduces inertia. It might be hard to convince an entire group to go off the beaten path. Though on the positive side, once a decision has been made, implementation might be easier since each team member will most likely already have bought into the strategy. They’ll be more enthusiastic, knowing that their voice has been heard.

Japan is unique in the way that decisions are made. In the so-called “ringi system” of decision-making, consensus is formed at each level of the hierarchy. And once that consensus decision has been made, the question is pushed up to the next level. Meyer believes that this system is time-consuming and introduces accountability issues, with little incentive to stand out and challenge the consensus.

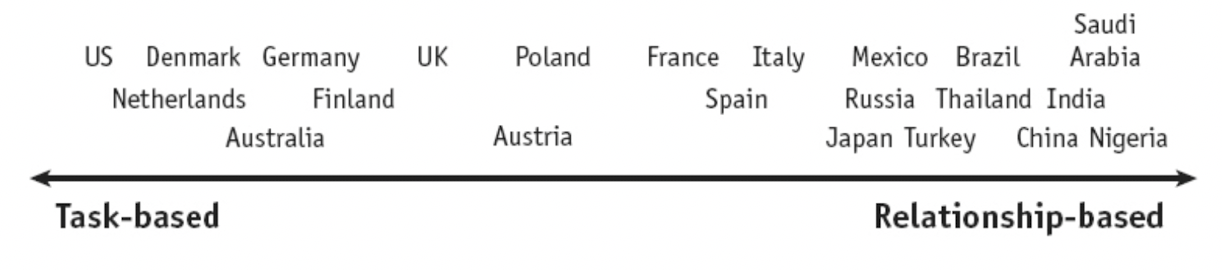

6. Trusting: the need for relationships

As anyone who has worked in emerging markets can attest, relationships matter greatly in business.

In many developing countries such as Brazil, trust is built up through relationships. Once the relationship is built, loyalty and openness come with it. And only then can deals start to take place.

Business in East Asia is often conducted the same way. Much attention is paid to relationships or “guanxi” in China, with no clear demarcation line between personal and business relationships. You’ll need a relationship for any favour to take place.

On the other side of the spectrum, you find countries such as the US, UK and Australia whose cultures can be said to be task-based. There’s a long tradition of separating the practical and emotional. You do the task assigned to you — no questions asked. It might even be seen as unprofessional to mix relationships with business.

Meyer argues that this dichotomy comes from the strength of countries’ legal systems. In countries with a strong rule of law, there is less need for trust in business relationships. You’ll know that the legal system will uphold your rights. Not so in most emerging markets, where your relationship is basically your contract. Ultimately, your network is all you can count on.

She also argues that Japan is a special case. There, people tend to follow tasks assigned to them during the day. But after work, people will go out drinking together to build a connection. They’ll think that by letting your guard down, you show that you’re an authentic individual with nothing to hide.

Friendliness doesn’t necessarily mean relationship based. Americans often smile at strangers and engage in chit-chat. But that doesn’t mean relationships have been formed. Conversely, a stony expression doesn’t necessarily mean arrogance or hostility.

The “trusting” dimension has more to do with whether a person is willing to work with you with or without an existing relationship. In the relationship-based cultures of East Asia, the answer is emphatically “yes”.

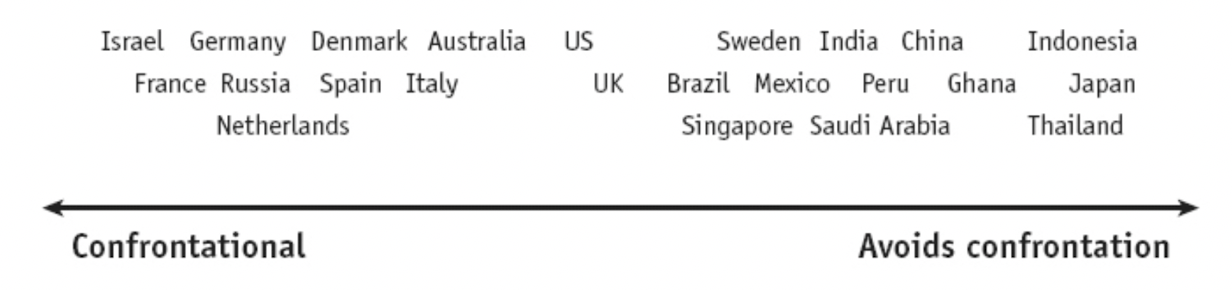

7. Disagreeing: embracing confrontation

The “disagreeing” dimension has to do with disagreement. To what extent will open disagreement between two individuals harm their relationship?

The most confrontational societies in the world are said to be France, Germany, Holland and Denmark. Everyone is expected to have different ideas. I’ve often heard people in Asia being put off by this combativeness, and I can understand why.

But the purpose of confrontation isn’t to attack the other individual. There’s this German concept called “sachlichkeit”, which translates into objectivity. This means that each person separates the idea from the person, being able to attack an idea without necessarily hurting the person’s feelings. People from confrontational cultures feel it’s important to challenge a proposal to determine its robustness.

Americans, on the other hand, often perceive dissent as a threat to their unity: “United we stand, divided we fall”. If you disagree with somebody openly, you’re almost disrupting the status quo.

In East Asia, Meyer argues that people try to preserve group harmony at all costs. Protecting someone’s “face” is more important than what you believe is correct. Even asking for someone’s opinion can be seen as confrontational.

But again, even in Confucian societies, there’s a difference between the behaviour of out-of-group individuals with those within the group. People may not treat outsiders the same way as those within the group, as we’ve seen repeatedly in history.

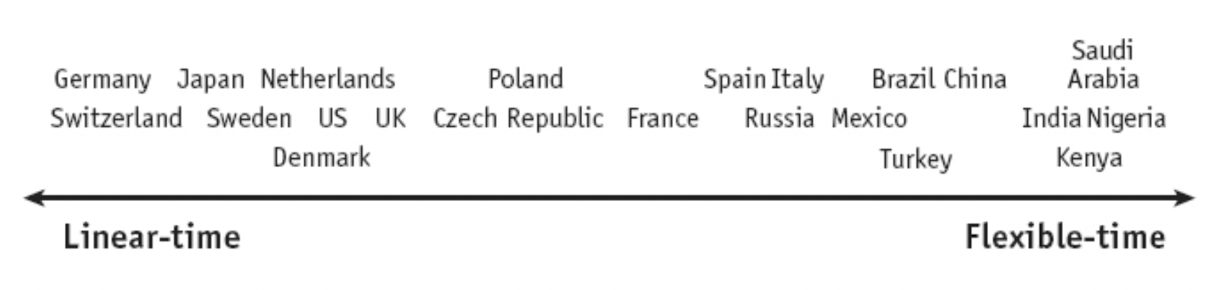

8. Scheduling: following the timeline

The final dimension that Meyer speaks about is how flexible we are with schedules.

Meyer argues that Northern Europe and the United States pay a great deal of attention to being on time. But the rigidness has to do with more than just time. They’ll also want things to go according to the plan in a linear fashion. As described by someone quoted in the book

“They expect us to work by carefully closing one box before opening the next”

In some European countries, individuals are basically on time. France and Northern Italy belong to these categories. You can come late to a meeting, but perhaps not more than ten minutes.

And then we have cultures working at a completely different time scale, those that tend to be flexible about time. India, Kenya, Nigeria, etc., belong to this part of the spectrum.

Europeans might consider people from such cultures lazy and unstructured. But the reality is that in societies characterised by constant change, planning ahead is impossible. That’s as true for traffic as it is for the weather, the effectiveness of government bureaucracies, etc. Nothing can be predicted with certainty. And people in these countries have simply learned to adapt by not paying too much attention to schedules.

Within East Asia, the Japanese are known to be highly organised planners. They are definitely closer to Germany in this respect than most of emerging Asia.

In China, however, everything seems to happen without preplanning. As a businessman in China quoted in the book said:

“The Chinese are kings of flexibility”

In other words, in mainland China, individuals don’t care as much about planning for tomorrow or next week but instead focus on the task at hand. But somehow, it all ends up working out anyway.

9. Conclusions

Erin Meyer has made her database public on her website erinmeyer.com, where you can also download nice visuals on how cultures differ. This is what the chart looks like for the Asian countries included in the data set, together with the US, the UK and Germany for comparison.

As you can tell, the Asian countries belong firmly to the right-hand side of the chart. In these countries, communication can be subtle, feedback is provided indirectly, group harmony is maintained at all costs, society tends to be hierarchical where decisions are taken at the top, and most countries are also more flexible about their schedules.

So why am I discussing a book on culture in a newsletter otherwise focused on investing? Because I think there are important lessons to take away from it.

One lesson has to do with interpreting messages. We need to see any communication through the appropriate lens. Read between the lines and pay as much attention to what is not being said as the actual words. Don’t expect people in Asia to be as direct as you might see in the Netherlands or Germany.

Another lesson has to do with predicting behaviour. Darwin believed that natural selection caused some animals to be better adapted to the local environment. Culture works similarly. An individual might be well-suited to his or her cultural environment but fail in another type. If a company hires a new CEO from a different culture, consider cultural compatibility to see whether he’ll succeed in his new role.

A third lesson has to do with comparative advantages. Living across continents, I’ve always wondered why certain companies from certain cultures do well in the global marketplace. Might their success be partly attributed to culture?

- Hierarchical organisations where decisions are made at the top might be better suited for industries with constant change and requiring the brilliance of a single individual to make leaps forward. Apple under Steve Jobs comes to mind.

- I hypothesise that corruption is less likely in cultures where communication is made explicit across the board. I also hypothesise that minority protection might be better in more task-based cultures, where relationships matter less for someone’s willingness to do business with others.

- I also wonder whether the persuading and scheduling factors influence whether a country's individuals are likely to succeed in engineering. Germans and Japanese are known for their engineering prowess, and they also happen to be principles-focused and rigid about schedules.

It’s hard to generalise across an entire population and perhaps quixotic to even try. But in any case, I found the book illuminating, and it will certainly help me view communication and behaviour in a different — cultural — light.

If you want to learn more about Erin Meyer’s work, you can find her book on Amazon here and her website here.