Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

- Closed-end funds are actively managed investment vehicles that rarely receive new money from investors. Instead, they trade like stocks and often at discounts to their net asset values.

- While the risk of trading at a discount to net asset value may seem to suggest that closed-end funds are inferior, I also think that the lack of redemption pressure allows fund managers to invest for the long term, even in illiquid securities, if they choose to.

- I have compiled a list of 49 closed-end funds focusing on equities in the Asia-Pacific region, most of which are listed in the United Kingdom or the United States.

- Towards the end, I highlight five closed-end funds worth paying attention to.

Here’s a quick note on closed-end funds in the Asia-Pacific region.

In Alice Schroeder’s book The Snowball, Warren Buffett spent a summer in 1950 analyzing closed-end funds. He’d go to his father’s brokerage office and browse investment company handbooks. At the end of the summer, he apparently put two-thirds of his personal portfolio in two closed-end mutual funds that traded at large discounts to net asset value.

That begs the question: can we find similar discounts among closed-end funds in the Asia-Pacific? In this post, I’ll try to answer that question.

I’ll also discuss why you might want to consider closed-end funds. And why ETFs are not necessarily the answer for those looking for funds to invest in.

Table of contents

1. What are closed-end funds?

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Pros and cons of closed-end funds

2. Valuing closed-end funds

2.1. Opportunity cost

2.2. Cycles in popularity

2.3. Fees and operating expenses

2.4. The accuracy of valuation marks

2.5. Catalysts

3. Universe of closed-end funds in Asia

4. Five highlighted funds

5. Conclusion1. Closed-end funds

1.1. Introduction

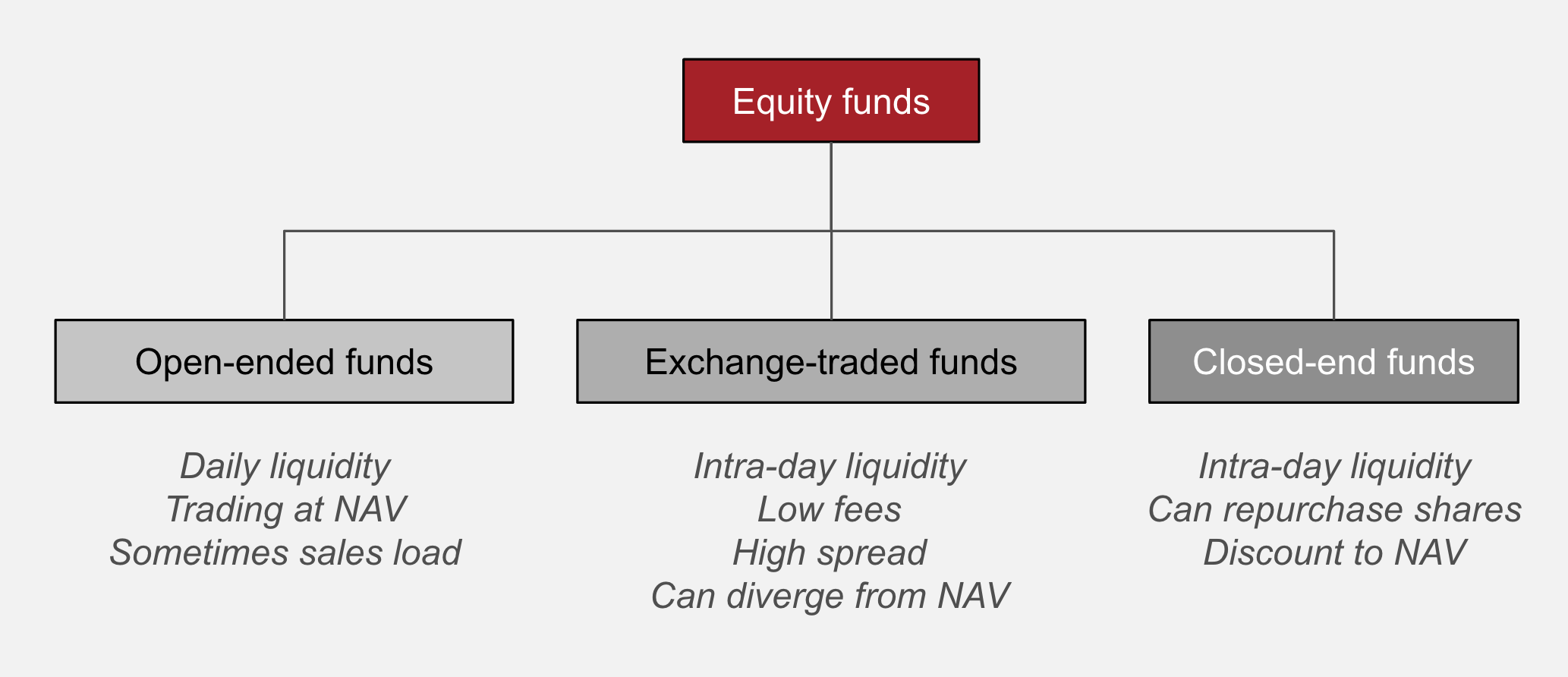

Equity funds can be divided into three main categories: open-ended funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and closed-end funds:

Open-ended funds continuously take in money from investors, issuing new shares to them or shrinking the share count in the process. Any investment or redemption will be dealt with at the end of each business day at the calculated net asset value of the fund.

Investors in Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) don’t deal with the fund directly. Instead, they buy the ETF on the secondary market. If the price of the ETF diverges from net asset value (NAV), authorized participants (banks) will create or redeem shares to remove the discount. That means ETFs will typically trade close to NAV, at least in normal circumstances.

Closed-end funds are actively managed investment vehicles traded on stock exchanges. They do initial public offerings like normal companies, selling a fixed number of shares to investors. Once they’re listed, they don’t deal with investors directly. Instead, investors will need to sell their shares on the secondary market. And that means that the price can sometimes significantly deviate from the fund's net asset value.

These closed-end funds have existed since 1893. They became popular during the US stock market bubble in 1928-29 and then fell out of favor after the Great Depression. In Asia, closed-end funds became popular in the 1980s, though more recently, new money seems to be flowing into ETFs instead.

1.2. Pros and cons of closed-end funds

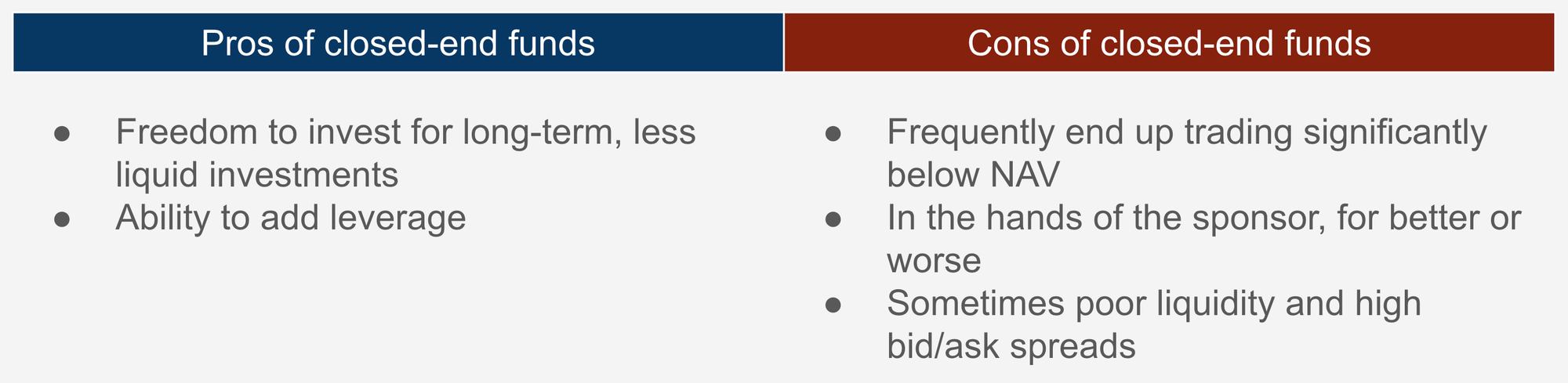

Today, most investors seem to think that open-ended funds are superior to closed-end funds and that ETFs are superior to both. But I think there’s nuance to that question.

While open-ended funds can be bought and sold at NAV, buyers often have to pay load charges to access the fund. In times of distress, when facing heavy redemptions, open-ended funds are forced to sell their holdings at whatever price the market is offering, whether those prices are attractive or not. They’ll essentially lock in losses at the worst possible moment.

I also think that exchange-traded funds remain untested. There’s often a liquidity mismatch between underlying assets and the ETF itself. As long as prices are stable and demand for the ETF, there is no problem. But at the end of the day, heavy price-insensitive selling of an ETF can also cause prices of the underlying assets to plummet, locking in losses as well. I’d stick to ETFs that do not suffer from liquidity mismatches.

So, I think there’s a case to be made for closed-end funds, which, in the right hands, can afford to be long-term and value-oriented. They’re particularly suitable for illiquid asset classes such as emerging market equities. They can also provide access to specific markets that foreigners will find difficult to access on their own.

There is a risk that closed-end funds will end up trading below net asset value. So alignment with the fund manager is crucial to ensure that the fund is not simply seen as a permanent capital vehicle designed to collect fees into perpetuity. I favor the ones that base their fees on the market price of the closed-end fund rather than the net asset value since the manager will then be keen to close the discount.

2. Valuing closed-end funds

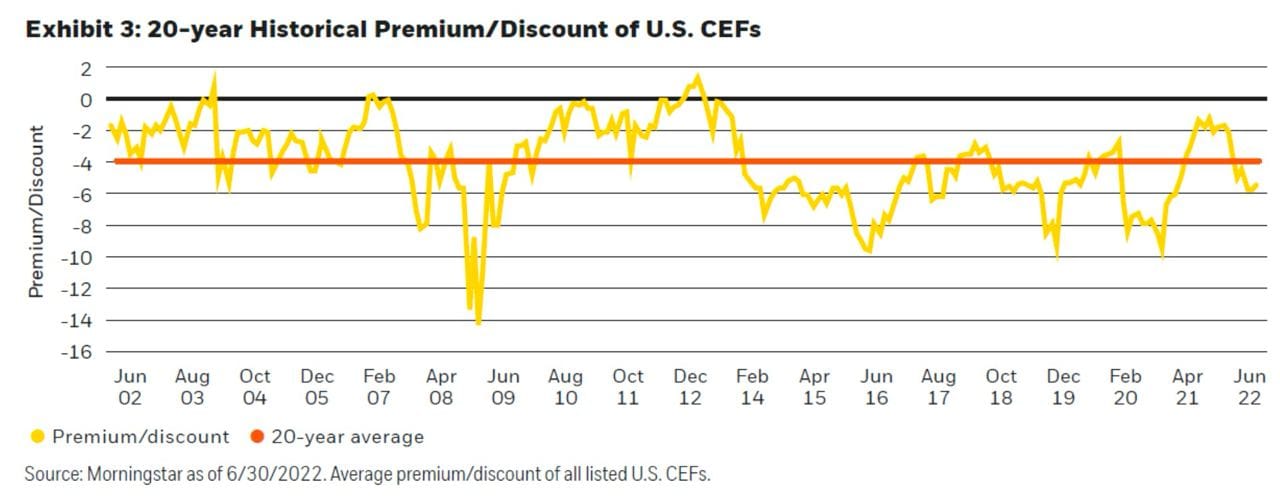

US-based closed-end funds have traded at a 4% discount to net asset value in the past two decades:

And they almost never trade above net asset value. So expect a small discount, on average.

Closed-end funds investing in illiquid, private equity-type assets can often trade as much as 50% below net asset value and stay there, sometimes for decades.

Why do these discounts persist, and what are the factors that go into them? I think it’s a combination of changes in opportunity costs, the popularity of different asset classes, fees and operating expenses, dubious valuation marks, and a lack of catalysts due to sometimes poor corporate governance.

2.1. Opportunity cost

Historically, these net asset value discounts have been high during times of distress. They were high in 2008 and were also high during COVID-19. I think that reflects a combination of risk-aversion and high uncertainty about what the underlying assets are worth.

Today, we also see risk-free rates much higher than the 10-year average. Why invest in risky assets when you can enjoy a decent return with close to zero credit risk? High interest rates become especially problematic if the fund itself has leverage, as it will also need to pay higher interest expenses.

2.2. Cycles in popularity

During the BRICs bubble of 2007 to 2010, closed-end funds traded up significantly. For example, a major India fund ended up with a 35% premium to NAV as investors couldn’t get enough of it.

Retail investors tend to chase either yield or short-term outperformance. So expect a higher discount when the yield is low, or the recent performance has been weak.

2.3. Fees and operating expenses

Fees to the manager detract from value, and calculated NAVs do not take the net present value of future fees into account.

They all charge management fees, but also operating expenses such as administrative costs, custodian fees, legal fees and marketing expenses, which are charged directly to the fund. For that reason, I like to look at the total expense ratio. Certain closed-end funds will also charge performance fees against a specific benchmark, which can subtract significantly from value, all else equal. These funds often trade at 20% discounts, if not more - for good reason.

2.4. The accuracy of valuation marks

Sometimes, portfolio holdings can be illiquid and, therefore, difficult to value. There may not be identifiable peers that can help investors understand the underlying value.

For private equity assets, the manager will have leeway in how the assets are valued. For example, changing the discount rate can cause the NAV of the fund to shift significantly. That can introduces a conflict of interest, and I totally get why investors can be skeptical of valuation marks.

2.5. Catalysts

The final point is that corporate governance probably explains the majority of the worst offenders in terms of wide NAV discounts. They’re managed by investment advisors who control the fate of the fund. Since they’re earning a decent fee from an investment vehicle that could theoretically live on forever, why rock the boat?

There are exceptions, specifically so-called term trusts, which are closed-end funds with a fixed termination or maturity date. I very much prefer those.

If a discount persists and the manager wants to deal with that problem, it can convert the closed-end fund to an open-ended fund, or it can be liquidated, merged, etc. And they can also buy back shares, provided that the mandate allows it to do so.

3. Universe of closed-end funds in Asia

So to summarize, NAV discounts are cyclical based on the popularity of particular assets and shifts in the interest rate environments. But they also reflect the net present value of future fees, the likelihood that the manager will treat minority investors well. And finally, whether the manager is likely to outperform its benchmark.

Over the past two days, I’ve tried to identify all the closed-end focusing on equities in the Asia-Pacific region. Here’s the final list that I’ve come up with: