Book review: Wild Ride

A book on China’s capitalist experiment by Anne Stevenson-Yang. Estimated reading time: 16 minutes

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

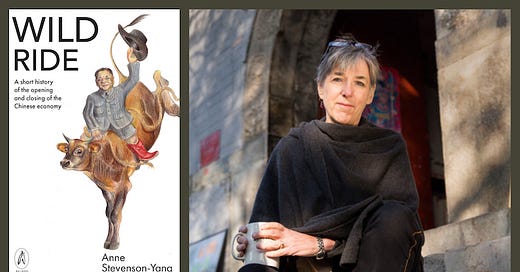

I just read a great new book by analyst Anne Stevenson-Yang. It’s called Wild Ride and is available for pre-order on Amazon.

The book tells the story of China’s economic miracle from the late 1970s until today - how Deng Xiaoping’s reforms unleashed a wave of entrepreneurship and led to China’s economy becoming one of the largest in the world.

However, it also discusses some of the system's fragilities and how the country now seems to be turning inwards again. And this is also the story of Anne’s life, which has mirrored China’s capitalist experiment in more ways than one.

Table of content:

1. Anne Stevenson-Yang

2. The First Decade (1979 to 1988)

3. The Gilded Age (1989 to 1998)

4. The Go-Go Years (1999 to 2008)

5. The Crisis (2009 to 2018)

6. The Retraction (2019 onwards)

7. Conclusion1. Anne Stevenson-Yang

Anne Stevenson-Yang came to China in 1985. She had been working as a journalist for BusinessWeek in New York but wanted a change of pace.

Once in Beijing, she joined the Chinese state publication China Pictorial - a propaganda magazine distributed to embassies overseas.

Her initial enthusiasm for Chinese-style socialism soon turned to disillusionment. For example, she learnt that healthcare was only available for the privileged urban class. The food was basic. And there was a housing shortage, with her young and unmarried colleagues sleeping at the office with no other alternatives.

At the magazine, she met a Beijing native Hindi translator called Zhifang Yang and ended up marrying him and attaching his surname to hers. But during those years, she increasingly felt living in close contact with her Chinese in-laws, trying to fit in and understand the language. So, they went back to the US for several years to recharge.

In 1993, an investment association called the US-China Business Council contacted Anne and asked if she might be interested in a position for her in Beijing. Her new role would be to promote foreign direct investment into China. She would meet with foreign businessmen and learn about the trials and tribulations they went through trying to make it big in the Middle Kingdom.

Over the next 20 years, she would witness the country transform into a modern economy. Anne herself built several successful businesses, including an online media business, a CRM software company, a publishing company, and a short-seller research firm called J Capital - which is how I learned about her in the first place.

In the book, she recounts being excited about the changes that were taking place in China at the time. The population welcomed foreigners with open arms, keen to learn about new technologies and absorb capital from overseas. She witnessed the fruits of Deng Xiaoping's reforms from 1979 onwards.

This is the story of how those reforms affected not just her but the Chinese population at large.

2. The First Decade (1979 to 1988)

China under Mao Zedong was a closed-off, repressive society. Meat was a once-in-a-week luxury. Cooking was done outside. And personal freedoms were more or less non-existent.

For example, your boss could permit or deny weddings, housing, and travel and even sentence you to labour camps. Women had their menstrual cycles monitored and had to apply for permission to get pregnant. This was an era drastically different from today.

After Mao died in 1976, a power struggle ensued. Ultimately, Mao’s former ally, Deng Xiaoping, emerged victorious from this struggle. One of his first tasks was to open up the economy to the outside world. For this, he would need hard currency.

Practical considerations took priority in those early years. When Deng Xiaoping travelled to the United States in 1979, he ordered an inventory of all hard currency in China’s banks. He came up with only US$38,000 - hardly enough to pay for his delegation.

This was a low point for the Chinese economy. Deng recognized that China needed exports. Japan, Korea, and Taiwan became wealthy by promoting the export of manufactured goods. So Deng adopted a twin strategy of promoting exports in special economic zones while shielding ordinary Chinese from foreign cultural influences. This worked beautifully, at least in the beginning.

Deng’s special economic zones were newly incorporated entities acting as quasi-governments. What made them different was that their managers were rewarded by meeting targets focused on the scale of capital investment and gross tax revenues. Such incentives aligned the interests of the managers of these special economic zones and the foreign companies looking for inexpensive labor.

Initially, foreign influence was kept at bay. Foreign nationals were required to live in special compounds, use separate medical facilities, and even use special currencies. Romantic relationships between foreigners and Chinese were forbidden as well.

The special economic zones in the Southern parts of the Guangdong province, such as Shenzhen, were particularly successful. One of the reasons was that they were near port facilities. But perhaps even more importantly, they had access to financial powerhouse Hong Kong, with its banks and talented entrepreneurs. While, of course, having access to hundreds of millions of workers from inland provinces.

In fact, Shenzhen became a model for the China that was about to develop. It was the first city to abolish the food coupon system, thus allowing residents to buy food with their own money. And residents were soon allowed to lease their own land.

Markets weren’t as liberal as they are today. Initially, foreign companies had to use a special currency that was traded at a huge premium to the Renminbi, China’s market price. And they also had to sell their products to state-owned enterprises at officially determined prices.

Another important part of Deng’s reforms was allowing farmers to grow whatever they pleased after meeting some quota. They could then sell any surplus in newly established markets. This unleashed immense rural income growth of 12% per year throughout the 1980s.

A similar system was later introduced to state-owned enterprises as well. They were now allowed to retain profits, either for reinvestment or pay them out as bonuses to employees. Managers suddenly realized they had incentives to increase revenues and profits, and some became wealthy.

Living in Beijing at the time, Anne recounts how supermarkets started opening in the city, with various fruits on offer. You could soon find any clothing you wanted - not just a single color and a single size. Some households were even able to install telephones.

But beneath the surface, discontent was growing. Students were devouring books brought in from overseas. They were clamoring not only for economic gains but also for political reforms. By 1987, Beijing students regularly held marches from the university districts to Tian’anmen Square to protect against political restrictions. Those protests would soon change the course of history, though perhaps not in the way the students intended.

3. The Gilded Age (1989 to 1998)

The crackdown on the student demonstrations in Beijing in June 1989 led to a significant political shift. For two years after the massacre, the country closed off, and dissidents were hunted down and jailed. Anyone who participated in the protests was either disappeared, jailed, demoted or unable to attend university or get a good job.

After the student protests, the Communist Party shifted its strategy to maintaining control. It upped its propaganda efforts, conveying that if the party were to collapse, China would end up in total anarchy.

In the aftermath of Tian’anmen, a communication system was established that improved the party's control over the provinces. Tax collection and audits were tightened, and a criminal detection and surveillance system was developed.

In the two years that followed, many entrepreneurs questioned the country's direction. But by 1992, Deng Xiaoping had reasserted control from the more conservative, leftist faction of the Communist Party.

Through a tour to the Southern part of China, he implicitly confirmed his commitment to reform, signalling to entrepreneurs that their activities would be encouraged, essentially taking private entrepreneurship out of the regulatory grey zone it had been in for so many years.

One of Deng’s buzzwords during this era was “to get rich is glorious” (致富光荣). You no longer had to be ashamed of pursuing wealth; it was promoted from the top down.

The Communist Party bet that as long as people felt their livelihoods improved, they would not rock the boat. The restive students who protested at Tian’anmen Square would now focus on economic opportunity rather than spiritual dissatisfaction.

After his come-back in the early 1990s, Deng picked out young talent Zhu Rongji to push for further reforms. In a long list of achievements, Zhu Rongji managed to:

Cut the government bureaucracy in half

Privatize housing

Sell off 2/3 of the companies in the state sector

Unify the dual currencies used prior to 1994

Introduce a nationwide tax system

Take control of the appointment of all provincial-level governors

During this era, it became normal for Chinese officials to seek best practices from other countries. Zhu Rongji was one of the proponents of such overseas trips.

Everyone seemed to be getting into business. For example, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) divested 20,000 companies under its umbrella, including farms, airlines, coal mines, hotels, etc. Former military men became the presidents of these companies, some of whom became household names such as ZTE and Huawei.

1991 marked the year when stock markets sprung up in Shanghai and Shenzhen. With the help of the government and senior executives, assets were consolidated into unified group structures and floated on exchanges. Many became rich in the process.

For example, Zhu Rongji’s son, Levin Zhu, became the head of the highly successful investment bank China International Capital Corporation (CICC). The children of Deng ended up overseeing the formation of an independent military-industrial complex. And the children of Li Peng built a new breed of independent power producers. The list goes on and on.

4. The Go-Go Years (1999 to 2008)

After the reforms of the 1990s, China’s economic growth really took off. Exporters in China’s coastal regions benefitted from the country’s admission into the WTO, and Chinese returnees started businesses left and right.

The outsourcing of manufacturing from Western countries to China was driven partly by the low labor costs but also by world-class infrastructure and lax environmental regulation. This lower cost structure made it difficult for companies that did not have a presence in mainland China to survive.

In 2007, Anne started a short seller research firm called J Capital. This company would go on to serve institutional investors in uncovering fraud among Chinese companies listed overseas. In this era, emerging markets like the BRIC countries were in vogue. Foreign investors clamored for Chinese exposure and got hurt in the process.

Some notable frauds that Anne came across during this time included:

Mazu Alliance: a company dedicated to the worship of a goddess called Mazu

Kuangchi Science: a company building apparatuses for space tourism

China Cord Blood: a company offering storage of umbilical cord blood)

Since the penalties were nearly non-existent, more and more such companies took advantage of foreign capital while the opportunity existed. Why not?

It was also during the 2000s that the property boom really kicked into high gear. In the late 1990s, Zhu Rongji instituted reforms that allowed state-owned enterprises to sell worker housing back to tenants for a pittance. As prices rose throughout the 2000s, tenants now held significant household equity, which they could then leverage to buy new, even fancier, commodity housing.

A change in the tax structure also incentivized local governments to promote construction. In the mid-1990s, the central government established its own offices to collect taxes directly. In other words, local governments had less ability to raise taxes themselves, instead relying on remittances from the central government. Local governments thus became cash-poor.

To fund their spending programs, they instead set up local government financing vehicles (LGFVs), which used land as collateral for borrowing. And since they were government entities, they were seen as quasi-sovereign borrowers enjoying full access to loans from state banks. Over time, the number of LGFVs grew to over 10,000. They operate urban infrastructure, subway systems, water and gas utilities, etc. Some of them are profitable, but many of them are not. And who will eventually foot the bill for this extravagant spending?

During the 2000s, it was entirely rational for households to invest in properties. Incomes grew over 10% per year, and property prices increased even faster. Compare those numbers with the financial repression experienced by depositors, who received a paltry 2% in interest on their savings. Property was clearly the better option.

The privatization of China’s housing market, which provided collateral for new loans, created one of the biggest credit booms the world has ever seen. Later on, in just five years, more credit was created than the entire value of the US banking system.

The boom in private sector entrepreneurship reached a crescendo around the Beijing Olympics in 2008. This was when the world decided that China’s time had finally come. The US$1 billion opening ceremony was choreographed by famous director Zhang Yimou, and factories were closed for months to ensure clean air during the Olympics.

But Anne believes that the 2008 Olympics marked a turning point in China’s development and that it marked a return to heavy-handed politics:

“The Olympic experience brought me to understand that China had not changed institutionally, and that the post-1979 experiment with capitalism was just that: an experiment that, when deemed to be no longer useful, would be discarded.”

5. The Crisis (2009 to 2018)

After the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, the Communist Party leadership unleashed a CNY 4 trillion stimulus program that brought forward demand for infrastructure and spending targets.

At this point, it was already becoming clear that the capital stock for infrastructure was starting to exceed those of most other developing or even developed economies. By 2012, China had 8x the length of highways per unit of GDP as that of Japan. At the time, more than 70% of China’s airports were failing to cover their own costs, even though such costs tend to be modest.

The stimulus was so large that officials had to compel local governments to spend the money and not just hold the cash. To get the money into circulation, banks hired call centers to offer unsecured loans to consumers.

The Chinese lending machine also went overseas. Anne describes the Belt and Road Initiative as an extension of China’s domestic economy, with high-level national targets needing to be met through aggressive lending. Recipients such as Venezuela, Sri Lanka, and Ecuador went into distress, and the loans are still being worked through.

Meanwhile, with the state pushing for big stimulus packages, the government increasingly directed economic resources. Concepts such as “advance of the state, retreat of the private sector” (国进民退) became more common, reflecting a shift in the economy away from private sector entrepreneurship.

Another effect of the credit boom was the creation of immense wealth. Today, Beijing has more billionaires than any other city - even compared to New York. The leadership must have asked themselves whether entrepreneurs like Jack Ma could one day threaten Communist Party supremacy.

And indeed, with the emergence of Xi Jinping, the state has started to reassert control. State companies are now receiving most of the loans from China’s banks. State media is now talking of “national rejuvenation”, trying to unite the country around nationalist sentiment and acceptance of a “moderately prosperous lifestyle” (小康社会). This is a clear break from the era of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms when getting rich was perhaps the greatest virtue in life.

6. The Retraction (2019 onwards)

The onset of COVID-19 caused the government to use control methods that have not been seen since the surveillance state of the 1980s and earlier. During COVID-19, people were told to keep others in check, just like with the Village and Street Committees during the Mao era. The Party had one over-arching goal: to minimize the spread of COVID-19, with other considerations taking the back seat.

But the pandemic masked another important shift: the end of the real estate miracle. With property prices now sluggish and lending cut off from private developers, residential new starts have now dropped by more than half. And a lack of land sales means that local governments are experiencing cash shortages.

She also believes that China will now move away from trade with Western nations and instead try to carve out a sphere for itself - not unlike during the Cold War. In her own words:

China and Russia may nudge us into a world where dictatorships try to develope their own transportation networks to further insulate themselves from Western sanctions.”

Further, she believes that a Russia-Iran-China bloc is currently being formed and that China’s financial system could serve as a bedrock for trade within the bloc:

“If, however, China were someday to shrink its network of trading partners to other dictatorships like Russia and North Korea, its dedicated financial system could become the principal one used for trade among those nations.”

In other words, Anne believes that China is withdrawing from its informal pact with Western nations about open trade, with the experiment in Western-style capitalism that commenced in 1979 over. The Chinese economy is now morphing into a different system, one where the state reigns supreme and will become an influential partner in a new trading bloc formed by China’s current geopolitical allies.

7. Conclusion

Anne moved back to the United States in 2014. By this time, her children with Zhifang had already grown up, and she decided it was time to head home, partly because of personal considerations but also because she no longer felt safe.

It seems to be true that China’s development has occurred in fits and starts, in periods of opening up and closing off. Perhaps we are now in one of those latter periods.

I’m not convinced the change will be as dramatic as some might fear. Private companies face weakening construction activity, reduced access to credit and meddling by Communist Party committees. But many of them are doing well, and I wouldn’t rule out continued global market share gains in specific sectors of the economy despite weaker headline GDP growth.

A return to Mao-era governance seems unlikely. While China under Xi has certainly become less free-wheeling than in the past, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the capitalist experiment is over. Though let’s see - only time will tell.

Thank you for reading 🙏

If you would like to support me and get 20x high-quality deep-dives per year and other thematic reports like this, try out the Asian Century Stocks subscription service - all for the price of a few weekly cappuccinos.

I think that US and the EU are in a secular decline which will benefit Asia LatAm and Africa. That is, IF they manage to not embroil themselves into war and fall for another round of "divide and conquer" tactics of the West. Steps are being taken towards cooperating, most notably the BRICKs. Nonetheless we are still early on. Politics aside, the most difficult macroeconomic issues for China that currently lie ahead IMHO are very well articulated in the following interview of Russell Napier. I think it it's well worth your time.

https://youtu.be/bkbDgNjyDTM?si=OWPa_G8Ma2LzkgCD

Well before COVID the US government had decided that China's economic growth was a serious threat to them and their world order. The "retraction" is mostly a logical reaction to Trump's tariffs and Congress's manifest hostility.