Table of Contents

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Today, I’m talking to Yilun Chen, who runs a hedge fund called Tiger Hill out of London. I know Yilun from the Value Investors Club, as well as Twitter, where he writes under the handle @1lemonaday. He has a global mandate but has exposure to Asian equities as well.

Hi Yilun! Could you tell us about your background, how you became involved in investing and what you’re doing now at Tiger Hill Advisors?

I started in primary school, when my parents were giving me monetary rewards for getting '1s', which are the top grades in Germany. There wasn't that much to do with money for a 10-year-old, so once I had few hundred Deutsche Marks my parents allowed me to swap some of my money for stocks in their portfolio.

If you may remember, that was the dotcom bubble, so I picked Nokia and CommerceOne out of their portfolio. It was great for the first year or so, but ultimately CommerceOne went bankrupt and Nokia went the way of the Dodo.

Many lessons were learned, but ever since, I have been intrigued by investing. When I was getting into investment banking, I knew I wanted to join the buyside, where I spent a few years doing special situations investing, and then started Tiger Hill with a partner, with a focus on well-managed companies in cyclical industries or geographies that have fallen out of favor with the investment community. Basically, I am looking for good companies when and where there’s not much competition.

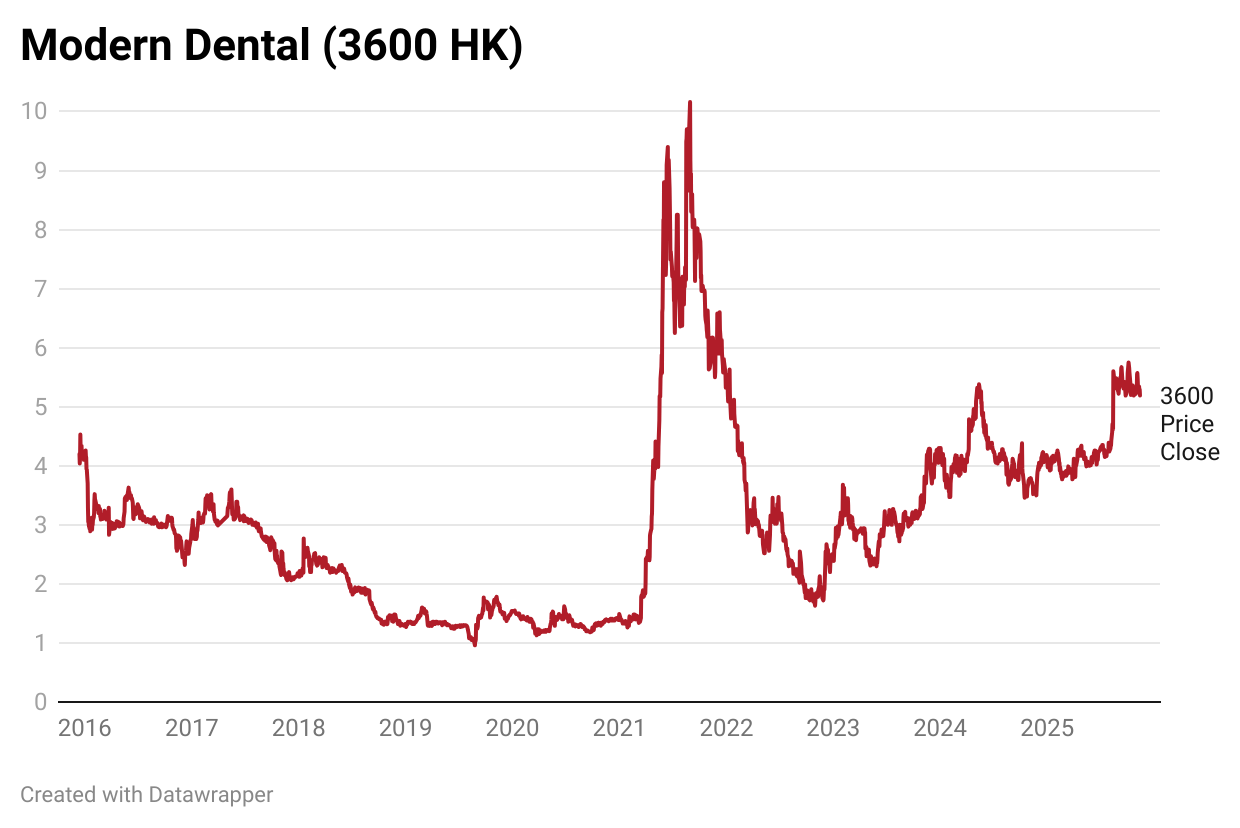

You wrote up Hong Kong’s Modern Dental (3600 HK) recently. I’m curious about your take on the stock today, given its success in Europe, its new CEO and the persistent fear that 3D printers will disintermediate the company?

I think Modern Dental's (1600 HK – US$624 million) success originally stemmed from its manufacturing prowess, but these days, it's a scaled and well-managed player who does a lot more than just manufacturing dental prosthetics. A mutual friend of ours, Healthy Stock Picks, has done great work on the company, so I will focus on 3D printing.

Predictions are hard but I am going to predict that "3D printing" is probably going to benefit Modern Dental eventually before it might potentially hurt it in the very far future. The biggest risk for Modern Dental is that "every dentist has a 3D printer at his desk" and out comes a crown. In that scenario, there would be no reason for Modern Dental's core business to exist, and Modern Dental management is acutely aware of this risk.

However, I think the more likely path is that there may eventually be large and expensive 3D printing machines that complement the dental technicians that Modern Dental employs, and it would be uneconomical for each dentist to have one of these machines in their practices due to the materials used.

Dental crowns are not made of plastic, which are commonly used in 3D printing these days, but made of ceramics, which are much more difficult to process. The crowns and bridges that Modern Dental produces are made of blocks of powders mixed with binding agents, which they first mill (see figure 1) and then sinter at 1,000+°C, to give the crowns the hardness and looks of natural teeth.

Conversely, thermoplastics commonly used in 3D printing have melting points in the low hundreds, even specialty plastics like PEEK only have melting points below 400°C. I am not saying 3D printing of crowns cannot be done, but desktop 3D printing based on today's technologies is uneconomical compared to existing manufacturing processes. Modern Dental's delivery times currently are ~7 days from taking a digital oral scan to delivery of the finished crown, also because Modern Dental has production sites all around the world. How much time and money can you truly save by having your own crown printing machine?

What is probably more exciting than 3D printing may be machines that can increase automation with regards to polishing and finishing of the prosthetics, but I digress. I think for the next decade, Modern Dental will be safe.

In China, we’ve seen sector after sector end up with overcapacity, eventually hitting the export markets. These sectors include solar, chemicals and now electric vehicles and batteries. What do you think is the underlying reason behind this pattern? And which export markets do you think will be vulnerable in the future?

I think the underlying reason is called capitalism, where the lack of a social safety net means that the average Chinese need to get off their bums and work, which naturally creates competition for clients, abundance of products, and both innovative and affordable products. A key tenet of free market capitalism is fierce competition between companies creating consumer choice and consumer surplus.

My parents told me stories of growing up during the truly communist times: even daily staples were in such short supply that you did not just need money, you also needed “粮票,” food stamps, in order to be able to buy rice, flour, or eggs. Today, you and I can stroll into the supermarket each day and decide whether we fancy bread, pasta, or rice, and our budgets will probably not be deciding what we're eating tonight. Around COVID-19, in London, we experienced rationing of toilet paper, flour, and eggs, which was thankfully only temporary (so far). Overcapacity is a feature not a bug of capitalism.

Unlike what many standard private equity guys are preaching about pricing power, I think they actually got the idea of "pricing power" wrong. It is natural for any given product that has required a lot of R&D to get cheaper over time: the R&D has been spent, and the marginal cost is much lower compared to the total average cost including the upfront R&D expenditure. I think this is called Wright's Law and this does not just apply to computer chip manufacturing but chemicals, autos, and most knowledge economy products. Basically, everything the Chinese are catching up on. Just think about cars from our childhood. I think the first car my parents bought was a Toyota where you still hand to hand crank the windows. I guess car makers wanted to increase prices over time so they added more features, removed lower priced models from the market. These are price increases that are OK. But I think the myth of having products where you can brainlessly increase prices is just a myth that has been propagated by certain business schools because it sounds smart, but it's neither realistic nor good for consumers nor even the companies themselves in the long-run.

What other industries are going to be vulnerable? I think a relatively obvious one is airplanes. Presently, this is a comfortable duopoly between Airbus and Boeing with very long backlogs and a complex and highly regulated supply chain. This is a typical setup for high profits and slow pace of innovation that gives the Chinese a lot of room to catch-up and to cut costs. It doesn't mean that the Chinese will be able to make every single last part of the plane, say turbines or turbine blades, but I think congressman Ro Khanna made a great point when he bemoaned that a small metal pin from TransDigm cost $4,000. The U.S. Government ended up asking for a refund and I think they got most of the money back. It's not communism, it’s common sense. Do I think that Airbus and Boeing are shorts? Not necessarily, these are national champions, and their supply chains provide a lot of employment, so I’m guessing the Chinese C919 and successors will struggle to make inroads in those markets. However, as we’ve seen with the German auto OEMs that used to derive almost 50% of their profits from China, I would want to be a lot more cautious paying a heroic valuation multiple for these guys.

What do you think of the big export powerhouses like BYD and Xiaomi then, given this backdrop?

That’s a great question to an age-old problem: Chinese manufacturers historically have been churning out unaesthetic low-quality me-too products, when are they ever going to build a decent brand? There’s no shortage of manpower or capacity to produce whatever one can imagine, however, how does one create a brand, a widely recognized and beloved brand? It’s not a trivial question, and when we started investing in Xiaomi (1810 HK – US$140 billion) in 2022, my hope was that Xiaomi could become the first Chinese consumer products brand with global cachet, like Apple or Sony. There are other Chinese players like Midea, Haier, or BYD but no one has embraced the Chinese manufacturing supply chain as shamelessly as well as successfully as Xiaomi, which ultimately led to their fairly successful launch of their car.

In fact, in my conversations with Xiaomi competitors, many “real” manufacturers looked down on Xiaomi: "they are not a real manufacturer, they just slap the Xiaomi label on products made by others and sell it as their own." There's an element of truth to this, but the critics were missing three important strengths of Xiaomi: design, marketing, and software. Due to the vastness of Chinese manufacturing ecosystem, Xiaomi didn’t have to good at manufacturing per se. Xiaomi is good albeit maybe not yet excellent at product design and quality control, but increasingly, this is also not sufficient to differentiate itself anymore: as many Chinese manufacturers are catching up to the Western brands and are increasingly pushing the limits of technology and innovation, being manufacturing pure play is tough. On the other hand, Xiaomi is great at marketing: they’ve successfully copied Steve Jobs in this regard, and are able to put through press and customers alike through 2-3 hours of new product introductions every year whilst many brands’ 10 second video clips on YouTube still get clicked away. On top of Xiaomi’s marketing prowess, of course, comes Xiaomi’s innate strength in software.

What's also important to me is that Xiaomi’s CEO, Mr. Lei Jun, at heart, is a nerd and really understands software. People forget that he studied computer science and was CEO of Kingsoft (3888 HK – US$5.7 billion) at some point. Increasingly, as home appliances are getting smarter, with Xiaomi’s strength in software, I think Xiaomi will have a growing advantage over many competitors with regards to user interface integration and remote control. For a Chinese company in particular, Xiaomi is pretty good at UI and UX, and in a world where the gadgets are increasingly getting "smarter" and connected, I think Xiaomi will be in pole position to also come up with products or drive adoption of products that we can't even think of today. I cannot tell you what they will do and whether they will succeed, but I can tell you that they will have setbacks and failed product launches. I don’t know if Xiaomi will be successful with its chip ambitions or AI initiatives, but I have faith in Lei Jun doing the right thing and continuing to drive shareholder value.

Personally, I like Xiaomi because their products offer great value for money as they are top or second quartile in terms of performance or quality at second or third quartile prices. When one buys from unknown Chinese manufacturers, one always worries whether it will work, and if it does work, how long it'll last. Xiaomi's products are often good enough for a few years, and given rapid technological advances, you probably want to get a newer and better replacement in a few years anyways. Furthermore, I believe Xiaomi is massively underpenetrated in developed markets. Internally, a few years ago, their view was in the West, they only want Xiaomi phones and not the other products. In their store in Westfield in London, they didn't even bother putting up the full breadth of their products. This is sad, but I hope and think they will fix this over time, because it’s a reasonable outlet for Chinese manufacturing capacity.

I know you're somewhat of an expert on the global chemicals sector. Can you educate us on how you approach the industry as a whole? What types of companies are you looking for, the risks of investing in the sector, etc.?

I think the most important thing about in investing in chemicals is to focus on making money as opposed to chasing some faddish megatrends or “specialty” labels, and to not forget about cyclicality and valuation. There are very interesting niches such as flavors and fragrances, chemicals for the semi-conductor industry, or high-performance plastics, however, in chemicals as in any other industry, I mostly focus on free cash flow and whether the companies run for their shareholders.

Take some of the most successful chemical companies for public market investors, the industrial gas companies. I mean, they take ambient air that you and I are breathing right now, run it through a compressor, separate it into nitrogen, oxygen, and noble gases mostly. It’s hardly chemistry, it’s physics! Some high purity medical and specialty applications aside, there is nothing special about these products or production technologies at all. However, once constructed, these guys act like utility businesses, and thus could get a lot of cheap leverage after the GFC to do M&A. Are these companies going be as great investments at 25x+ PE as they were in the high-teens PE a decade ago? I don’t know. But they sure beat a hell of a lot of businesses that went to chase the specialty chemicals segments.

It pains me to say, but it is very difficult to invest in Western chemical companies, even at today’s modest valuations, because (a) few are focused on making money for shareholders, (b) many assets are structurally challenged, and (c) regaining competitiveness will require some political and societal changes in attitudes towards the so-called “decarbonization.”

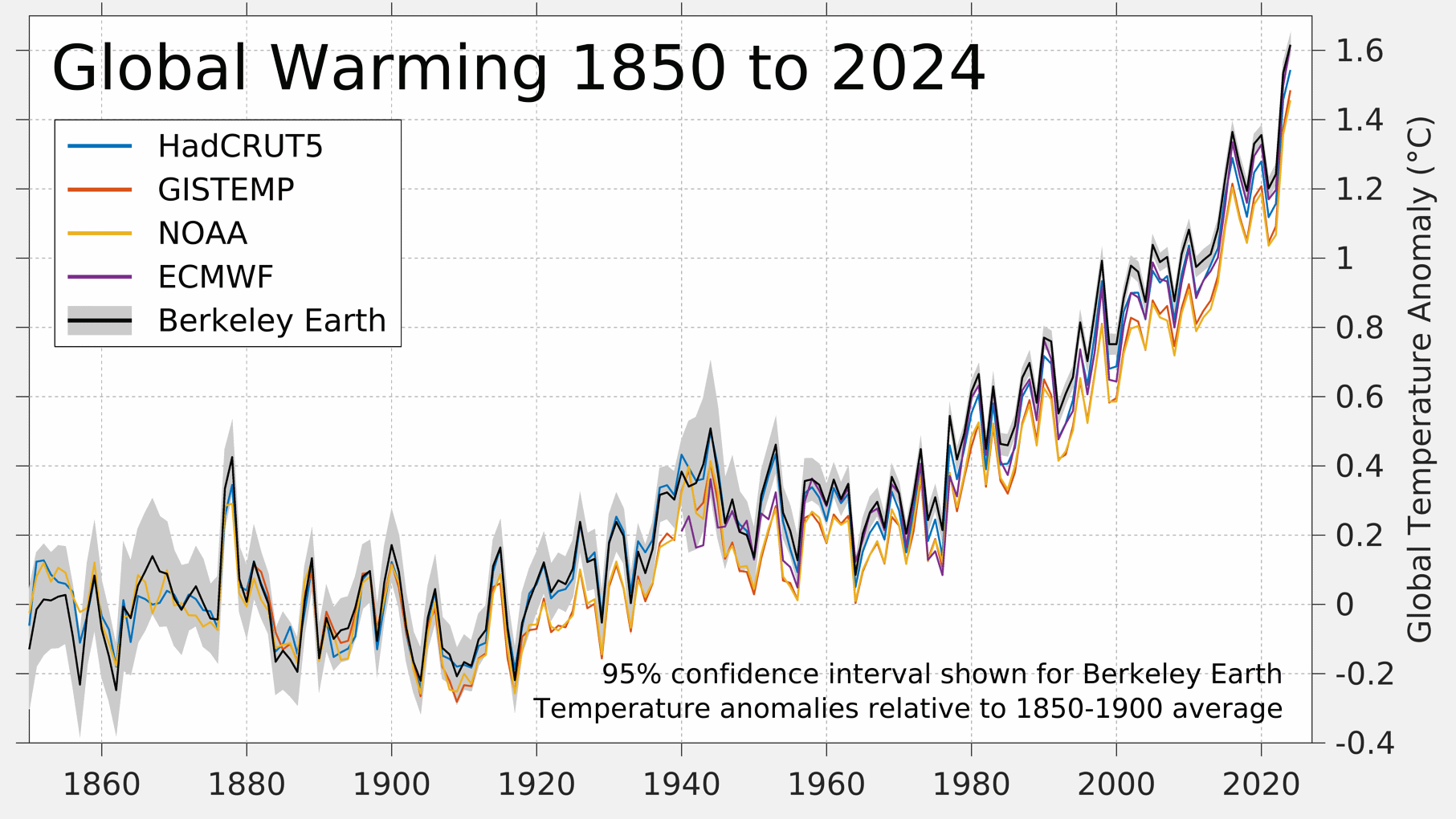

I believe in climate change, and I think reducing emissions is a good idea, but EU efforts in particular have done little to cut emissions but have done a lot to take Europeans back towards the Middle Ages. Any (human) activity creates emissions, and the way the Europeans are implementing various carbon taxes will ultimately just lead to its deindustrialization, plain and simple. High energy prices, partially due to carbon prices, discourages manufacturing. If all widget becomes made-in-China, then we also do not need to produce the plastics, the magnets, and the metals to make these widgets in Europe. European efforts to curb the production of fossil fuels raises the cost of raw materials and intermediate products. Why should we be surprised that the chemical producers are becoming increasingly uncompetitive in Europe?

Feedstock and energy prices aside, I think we also have to acknowledge by now that on top of a vanishing supply chain, European chemical plants are old and small. As with computer chip fabs, new plants may be more expensive but are probably a lot more productive than older plants. The newest plants are now in the U.S. thanks to the shale oil boom, in the Middle East due to an abundance of oil and a strong desire to do something with their valuable resources other than just blindly exporting it, and in China where most of the world’s widgets are being manufactured. European chemical companies still dominate many niches, but how long for? And if your customers, neighbors, and suppliers are shrinking, it will be challenging for European chemical companies to maintain current profitability levels. Is buying such businesses at 10x historical through-the-cycle average earnings good value or is one buying a value trap?

Germany has spent $200bn on green subsidies according to the New York Times, what does it have to show for? No solar industry to speak of, and one (still) leading wind turbine manufacturer. That’s it. Meanwhile, the Chinese have gone from being technological backwater to the world’s leading manufacturer and installer of solar and wind capacity, now frequently enjoying negative power prices in the middle of the day. It’s wonderful for the world, wonderful for people who want to see the world to decarbonize, but very scary for those who may own stranded assets.

Last year, you launched a strategy solely focused on China. What was your rationale?

Our investment strategy is to look for great companies at reasonable prices, and often we find the best investment opportunities when an entire sector or country has fallen out of favor with the investment community. In 2020, this strategy led us to allocate 60% of our generalist portfolio into oil and gas and ancillary sectors. Back then, we were a bit smaller and a bit too green to raise a dedicated fund. But by 2024, I was so convinced of the investment opportunity in China specifically that I decided to raise funds just for our China investments.

Whatever we like tends to be the “non-flavor-of-the-month,” but that’s how we find the most exciting opportunities with the least competition. Early last year, Xiaomi was trading below IPO price from 9 years ago, although not precisely low multiple PE at 24x or 18x when adjusted for the net cash. But there are many companies like Modern Dental that were trading well below 10x cash earnings and paying a high single-digit or low double-digit dividend, with long growth runways.

I’m not going to lie, fundraising has been tough. Many don’t even want to have a conversation. In 2020, the reason was ESG, no one wanted to touch fossil fuels, in 2023, people were worried that China’s People’s Liberation Army was going to land in Taiwan any day and TSMC was trading at 12x earnings. I don’t own TSMC but I agree with DaBao, who I believe you also interviewed in the past, that TSMC is one of the best businesses in the world, and sometimes it is available at a pretty reasonable price. Whether oil and gas 2020 or China 2024: when we got excited, all of the sector specialists and country specialists were down over a 5- or 10-year horizon. And this puny generalist shop knows better than them? We don’t know better, we just get in at much lower valuations and hope that the management teams just perform. For the past 3 years, we have been very bullish on China and especially Chinese equities, and we will continue to be bullish maybe for another 3-4 years. And then we’ll find something else to do.

You’ve been skeptical about Chinese fintech companies in the past. Many of the larger lending platforms appear to have direct balance sheet exposure, including financial guarantees. Is the sector investable at all, in your view? And how do you think regulation is going to develop from here?

I suppose we are talking about the Chinese online consumer lending platforms, which have in some ways evolved from the wild peer-to-peer (“P2P”) days into their current shape. Yes, I do think most of them were very challenging propositions back then, when they were pretty much shadow banks and regulators had good reasons to go after them, and yes, I do think they are investible now. They are not easy to understand, but today, I believe they are very well regulated, and thanks to some current regulatory concerns, also exceptionally cheap with strong capital return programs in place. I’ll give an overview of the history of these businesses and how we got to where we are today.

The industry got started around 2007, when the first online lending platforms emerged as P2P lenders. If you think about it, they are nothing but banks: they take money, i.e. deposits, from some people, lend it out to others, i.e. loans. Bear in mind that the banking sector in China is exceptionally sleepy and risk averse, because practically all of them are SOEs. There was and still is real demand for innovative financial products, including unsecured consumer lending, which was a void that the P2P lenders filled. Unfortunately, this sector also had the usual issues of unregulated unsecured lending: sky-high default rates due to inappropriate lending to vulnerable borrowers, objectionable collection practices, and regular busts of borrowers or platforms resulting in quasi-depositors frequently losing money. And bear in mind, within the Chinese fintech world, we don’t just get the pure P2P lenders of today, but also behemoths such as Ant Financial or WeChatPay. It was the wild west.

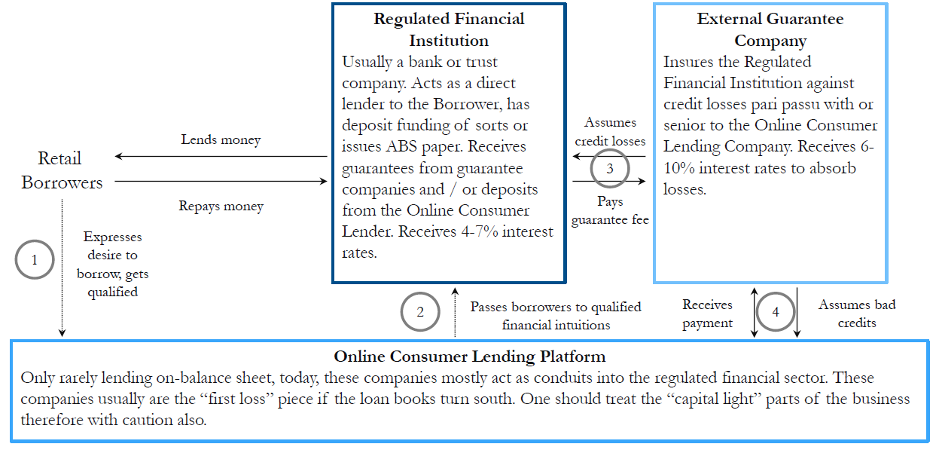

Over time, various government bodies come out with various rules and interpretation of the rules, such as interest rate caps, information sharing requirements, and guidance on collection practices, which ultimately resulted in today’s industry structure. Today, the former P2P lenders have turned themselves into something that practically resembles the U.S. credit card lenders like Synchrony Financial or CapitalOne. Strictly speaking, the Chinese online lending platforms attract and prequalify borrowers, and then pass on the client files to regulated financial institutions, which usually are smaller financial institutions such as rural banks. Chinese rural banks are normally deposit rich but asset poor, and given today’s low rates environment in particular, these rural banks are quite keen on earn a decent spread. Due to the banks’ regulated status, this also means that the effective funders for such loans, the banks’ depositors, enjoy deposit insurance. The institutional funding partners for the Chinese online lending platforms, be it rural banks or trust companies, also get guarantees from third party guarantee companies and the platforms themselves. Below is a simplified illustration of the various parties involved and how the information and the money flows.

I think today, this sector is investible, despite the uncertainty the recent pronouncements by China’s supreme court, the People’s Supreme Court, have brought in April 2025. Today’s industry structure helps the rural banks solve their asset issues, because these loans yield 4-7% for them net of all expenses and credit losses, which is very good in today’s near-ZIRP environment in China; funders have deposit insurance protection, so they don’t face random losses of principal; and borrowers can get unsecured short-term consumer loans at competitive interest rates even by international standards. In fact, given the Chinese rules stipulate that the IRR of loan-related costs must not exceed 36%, I think the Chinese regulation here, for once, is almost better than in the U.S. or U.K. where lenders charge late payment fees and what not.

In April 2025, the People’s Supreme Court came out with a bunch of guidelines, including a reminder of the 24% interest rate cap, which has led to a decently sized selloff. I personally believe that ultimately, they do want to increase transparency for consumers, to reduce complaints, and to reduce cost for borrowers, and why not? Chinese base rates are down 300-400bps depending on what you are looking at, and obviously the Chinese government is trying to stimulate domestic demand after a pretty epic housing bust. However, given the links to the regular financial economy, as a regulator, I’d be very careful to not intentionally cripple the online consumer lending sector, because this will also affect regulated deposit taking institutions and guarantee companies as well as the marginal borrower. So far, we have seen very little evidence that the government will come after this sector as hard as they have done to the education sector in 2022/2023, but this will is a risk and always will be for investors in this sector.

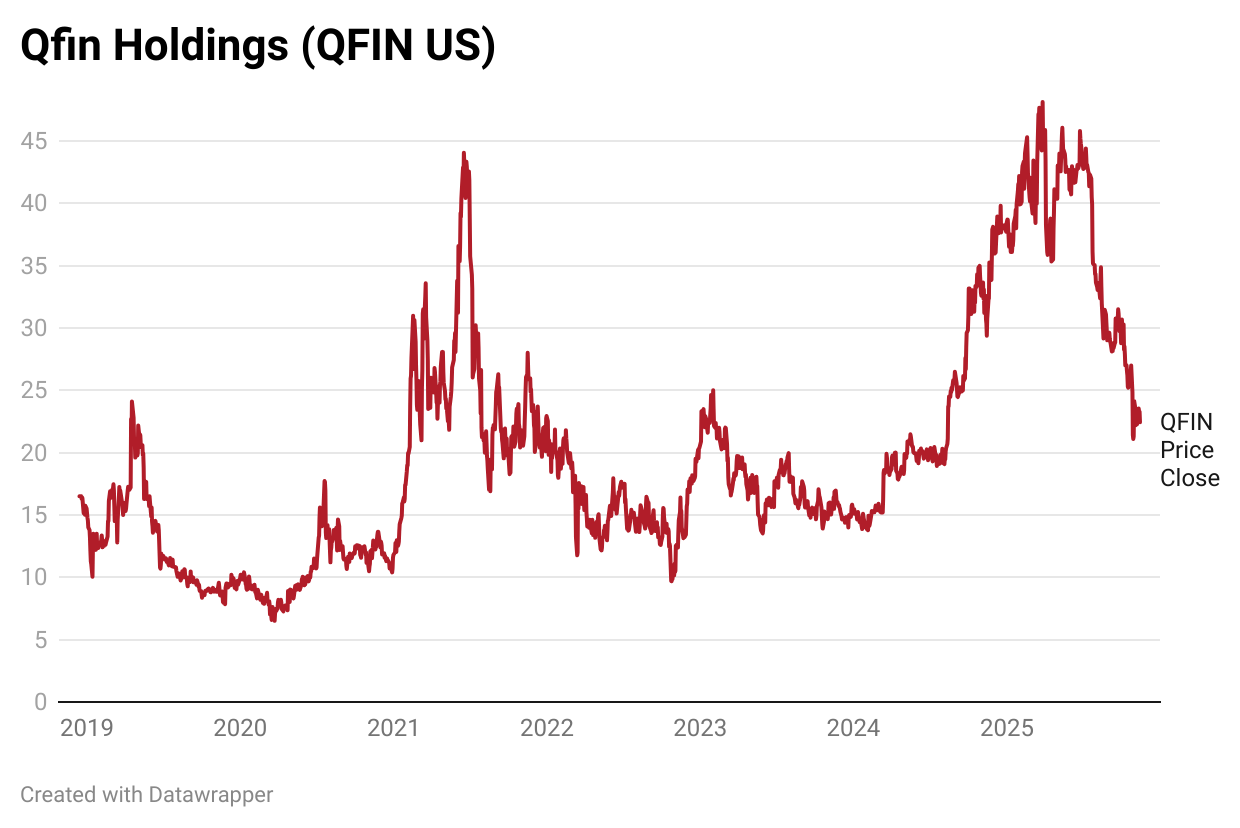

How’s the balance sheet and the current valuation of Qfin Holdings, in your view?

Qfin Holdings (QFIN US – US$3.0 billion) is probably one of the better houses on the pure play Chinese Online Consumer Lending street, with high-quality assets and a very diverse funding base.

QFIN is also the largest pure play online consumer lending platform, with the peers being LexinFintech (“LX”), FinVolution (“FINV”), XY Financial (“XYF”), Jiayin (“JFIN”), and also Yiren (“YRD”). They all have their quirks, e.g. LX has gotten itself into ecommerce and embeds its lending platform in it, FINV derives a solid amount of revenues from outside China, etc., but their Chinese businesses are in direct competition with each other. And these are not even the biggest guys: the big internet platforms, be it Ant Financial, Tencent, ByteDance, or Trip.com, all have their own consumer lending platforms, but they are comingled with a bunch of other businesses, but whilst I don’t spend too much time on them, they are frankly larger and systematically more important than the listed pure play peers that we are discussing here.

QFIN is a name that is easy to like: it has historically enjoyed the lowest delinquency rates, and as a result, has offered loans at lower rates than peers, whilst also having the very high loan loss provisions. Furthermore, QFIN is also overcapitalized in my view, even if one treated the “capital-light” parts of the business as “capital heavy,” which has enabled it to fund generous share buybacks. If one was to take the People’s Supreme Court pronouncement from April this year very literally, QFIN is probably also going to take a smaller hit to earnings compared to peers because (a) most of their loans are held on its own balance sheet and therefore had rates below 24% anyways, (b) only part of the off-balance sheet loans it was originating carried effectively interest rates of more than 24%. I have to point out that as a secondary effect from the rule changes, QFIN may suffer from enhanced competition for sub-24% borrowers because everyone else, at the margin, may try to originate loans below 24%. However, this is hard to quantify, because many smaller players are also expected to exit the market altogether. At 4-5x earnings (after-tax and LTM), a lot has been priced in, although I have to point out that U.S. unsecured consumer lenders like Synchrony Financial also only trade at around 8x earnings, which is also interesting but that’s a story for a different day. But what about the China risk? Which country has the more stable political framework for consumer lenders, China or the U.S.? Under the Biden administration, the CFPB tried to put into force rules to curb late payment fees, but after 2-3 years of litigation, this idea was dropped under the Trump administration. It’s a tough call.

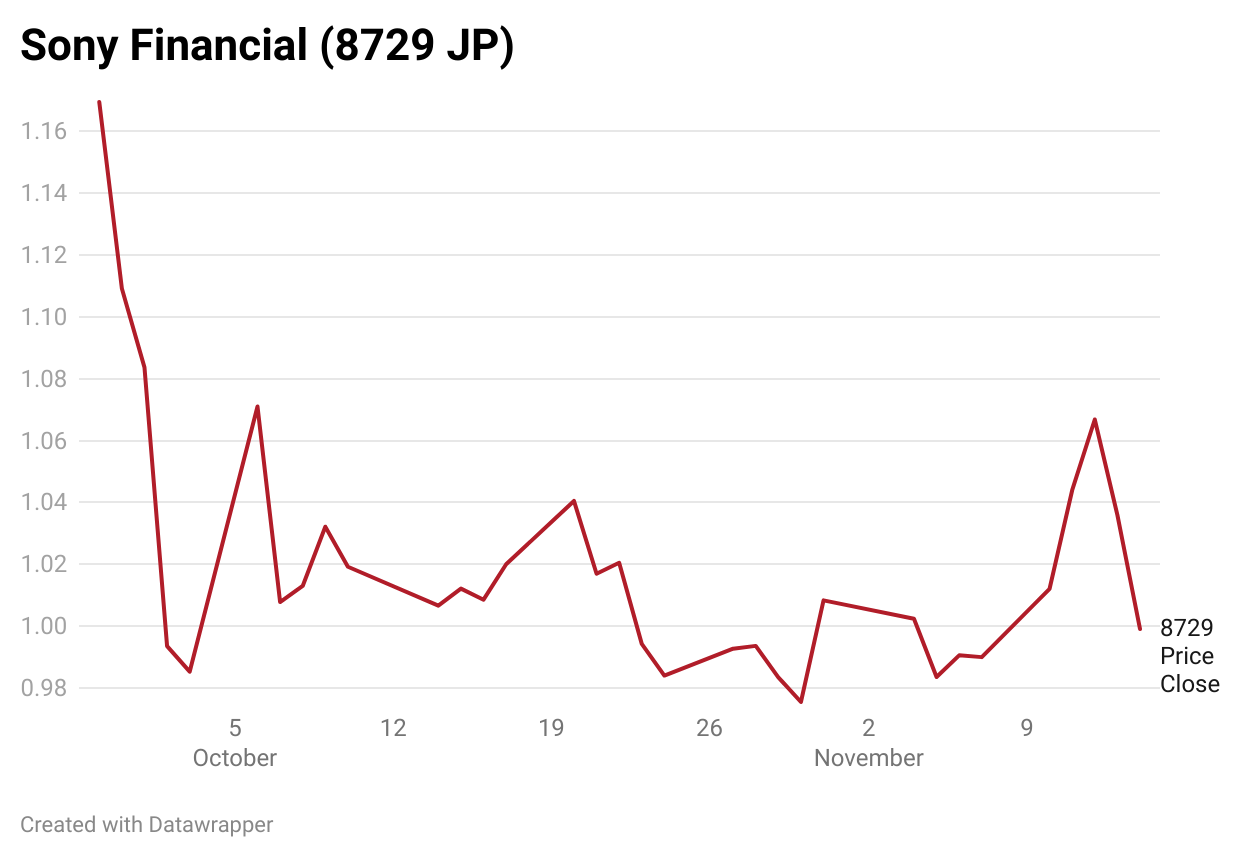

I loved your take on Sony Financial on Twitter the other day. Spin-offs are incredibly rare in Japan, so that’s why I’m following the name with great interest. Could you summarize your views on the company today?

Thank you! I have to admit that I have only invested in a handful of spin-offs and only one life insurer over the past decade or so, so when Sony Financial Group (“SFG”, 8729 JP — US$7.0 billion) came along I got quite excited, also because life insurers have obnoxiously complex accounting and regulatory capital rules.

You can read the thread here, but in a nutshell, I think SFG is not particular interesting in the ¥150 context despite its large buyback because:

- Its capital levels are modest, which are determined based on J-GAAP figures, are not that high at 184% (consolidated) or 168% (unconsolidated) against a stated minimum target of 165%,

- The buyback is going reduce capital by another 8pp and I estimate that SFG only generates around 10pp in capital every year ceteris paribus, which is, again, measured in J-GAAP and not based on IFRS earnings, and

- SFG is a lot more rates sensitive than its peers, with a 50bps rates move impacting capital levels by a whopping 18pp. Of course, the Fed is lowering rates at the moment, but given the monetary and political situation in Japan, I’d rather be careful.

Overall, SFG appears to trade at around 10-12x J-GAAP earnings, which is what the regulator looks at to approve distributions, so right now, the market offers much more interesting situations in my view.

Thanks for participating, Yilun! How can people contact you or follow your work?

Thanks for having me. They can follow us on Twitter, sign up on our website, or drop me an email via ychen@tigerhilladvisors.com.