Table of Contents

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

- Prabowo Subianto will become Indonesia's president in October 2024. He has pledged to continue President Jokowi’s reforms, including building a new capital in East Kalimantan and pushing for the continued industrialization of the commodity base.

- However, given Prabowo’s background as a military commander during the years of former dictator Suharto, it’s not clear what his long-term ambitions are. He has spoken favourably of Suharto, which begs the question of whether we’ll see a return to Suharto-era policies, including greater state ownership and state control.

- At the end of the post, I’ll also discuss the likely implications of Prabowo’s presidency on the Indonesian stock market and the currency.

In the past few days, I’ve been hooked on Netflix’s new drama Cigarette Girl on Netflix. It’s taken Indonesia by storm, depicting the lives of kretek cigarette makers in a quiet town in the 1960s, a few years before the rise of Suharto.

I argue that Indonesia faces a similar political shift today, from democracy to authoritarianism. On 14 February 2024, former defence minister Prabowo Subianto was elected the new President. He has a military background, having served former dictator Suharto and speaks favorably about that era.

Analysts seem to think Prabowo represents continuity, but I’m not so sure. We will know what his intentions truly are only when he takes office in October 2024. In this post, I’ll discuss Prabowo’s rise and its implication for Indonesian equities and the currency.

Table of contents

1. Jokowi’s legacy

2. The 2024 General Election

3. Prabowo Subianto

4. Investment implications

4.1. The broad perspective

4.2. Individual stocks

5. Conclusion1. Jokowi’s legacy

Since 2014, Indonesia has been run by businessman-turned-politician Joko Widodo, also known as “Jokowi.” He was the first Indonesian present who didn’t come from a military background or a prominent Indonesian family, and he’s been almost universally liked by the Indonesian people.

He was born in a poor neighborhood in Surakarta (also known as Solo) in Central Java. Being a diligent student, he secured a seat at a university. After building a furniture export business called Rakabu, he set his sights on politics and first became mayor of Solo and then president of the entire country.

During Jokowi’s tenure, there’s been significant positive change:

- He’s pushed to construct infrastructure such as toll roads, ports, airports, etc. For example, between 2015 and 2018, the Jokowi administration built 718km of new toll roads, compared to 229km during the preceding decade. Examples of such roads include the Trans Java Toll Road, connecting Jakarta with Surabaya and other cities across Java. Construction on a new subway in Jakarta began in 2013. Indonesia now has a high-speed rail between Jakarta and Bandung. A new airport called Kertajati Airport is being built in the Eastern part of Jakarta. And most of these projects were financed domestically without burdening the government budget too much.

- Thanks to Jokowi, a new city called Nusantara is being built on the island of Kalimantan. It will replace Jakarta as Indonesia’s capital city. Construction began in 2022. The purpose of this new city is to redistribute development to Kalimantan, a poorer part of the country, and ease the burden on Jakarta, which is both the commercial capital and the centre of government. The first 6,000 servants are expected to move to Nusantara by the end of 2024.

- There’s been an industrialization of the commodity base by forcing companies to undertake refining processes within the country, including for nickel and bauxite. The number of Chinese-based nickel smelters for example has gone up significantly.

- Jokowi’s proposed Omnibus Law on Job Creation was finally passed in 2023 after amendments. It’s intended to increase foreign direct investment into Indonesia by dealing with some of the hurdles that businesses have been facing. For example, it makes it easier to hire and fire employees, abolishes minimum wages by sector, lowers the corporate income tax, makes it easier for companies to acquire land, offers tax breaks for companies undertaking investments, relaxes foreign ownership restrictions, etc.

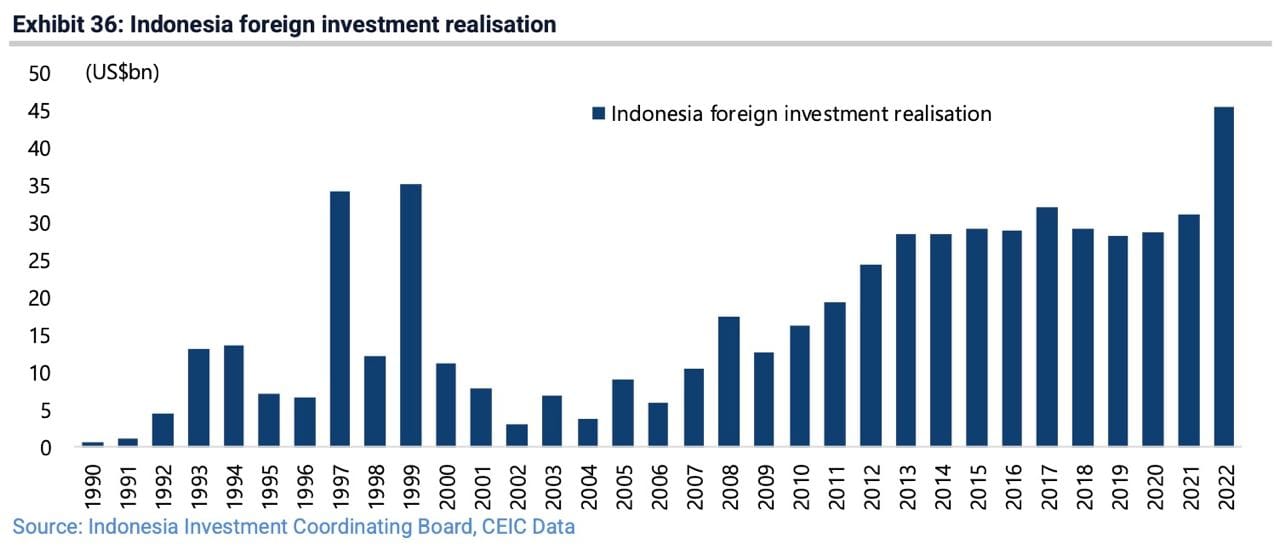

Foreign direct investment into Indonesia has now started to rise, driven primarily by investments from China. But there’s also the potential for multinationals to relocate production from China to Indonesia as part of the broader trend of “friendshoring”.

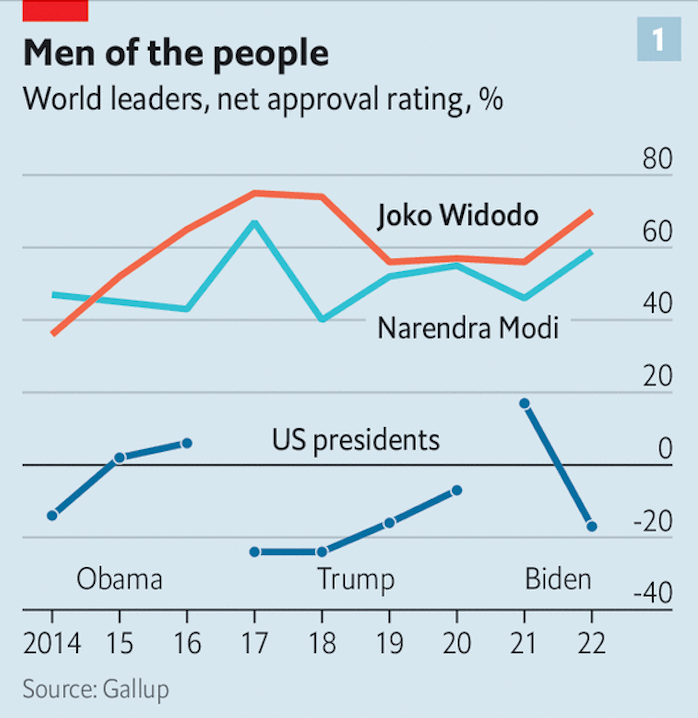

Jokowi has been hugely popular. Opinion polls have given him net approval ratings above 60% for most of his presidency, higher than Narendra Modi's.

But there’s also been clear regression in several areas. For example, in the run-up to Indonesia’s 2024 General Election, Jokowi tried to remove the two-period term limit, enabling him to stay on as President. There was a huge popular backlash against these efforts, and he had to step back from his ambition to stay on as President.

He then tried to engineer other ways to maintain power, including nominating two of his sons to compete in the election. His 36-year-old son Gibran Rakabuming (“Raka”) teamed up with defense minister Prabowo Subianto. Jokowi’s second son, 28-year-old Kaesang Pangarep, was made head of a youth-oriented political party called the Indonesian Solidarity Party.

When his son Gibran encountered legal challenges to his vice presidency, Jokowi influenced the Constitutional Court through his brother-in-law to remove the 40-year minimum age requirement so that he could qualify.

Under Jokowi, critics were often charged with defamation. The Islamist opposition party Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) faced investigation and criminal charges that seemed to be part of a power struggle. Jokowi also undermined the authority of the anti-corruption commission, probably to consolidate his own power.

The question is, what will happen now, given that Jokowi is about to resign and his current defense minister, Prabowo Subianto, is taking over as president?

2. The February 2024 General Election

On 14 February 2024, Indonesia held a General Election. Voters across the country elected a President, Vice President and lawmakers.

Prior to the election, three major alliances had been formed:

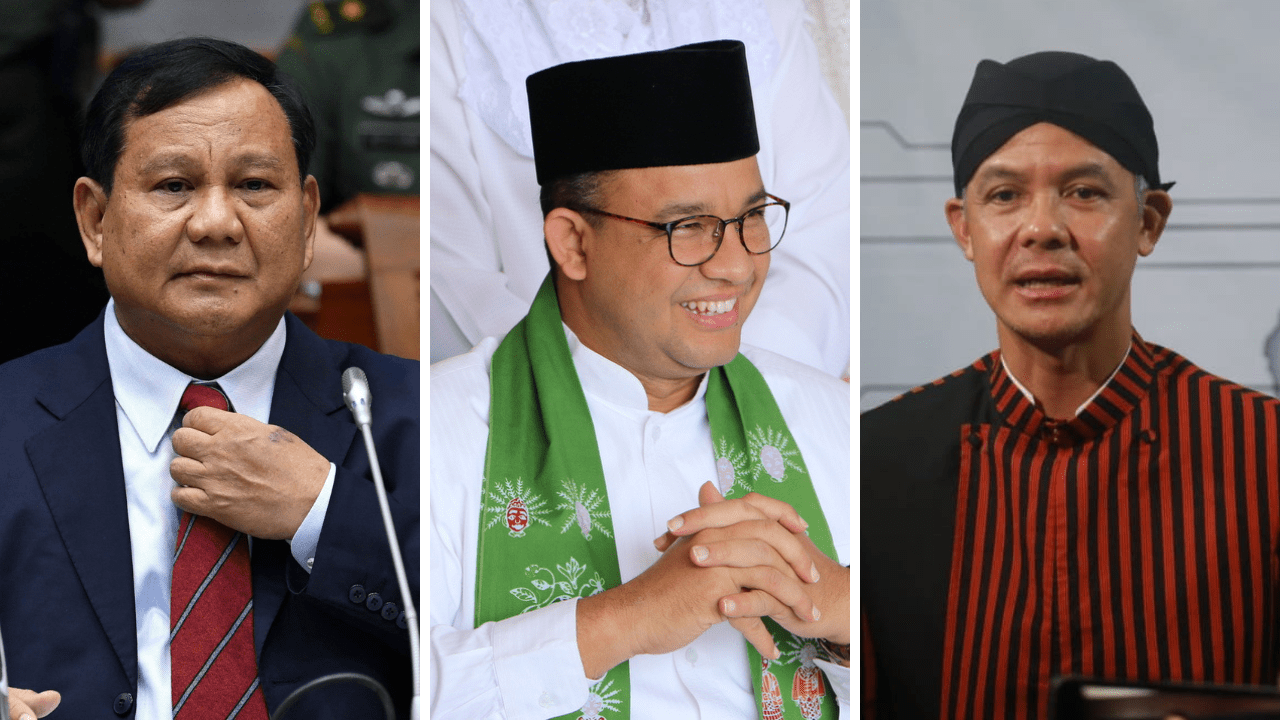

- Jokowi’s defense minister and former general Prabowo Subianto, supported by his political party Gerindra, Golkar and semi-Islamist party National Mandate Party. Prabowo is a centrist who campaigned on the promise to continue Jokowi’s reform agenda.

- Former Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan was supported by a coalition of the the National Democratic Party (NasDem), the Islamist Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) and the National Awakening Party (PKB). Baswedan pushed an economic plan that focused on labor intensive industries such as making shoes and furniture.

- Former Central Java governor Ganjar Pranowo who was supported by Jokowi’s party Indonesian-Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) and the Islamist United Development Party (PPP). Pranowo pushed for greater spending on education and healthcare.

In October 2023, Jokowi’s son Gibran Rakabuming - often jokingly referred to as the “nepo baby” - would team up with defense minister Prabowo and serve as his Vice President. In Indonesia, Vice Presidents don’t have much power, but the nomination represented an implicit endorsement by Jokowi of Prabowo’s presidency. The population became convinced he would be the safe choice for those who wanted continuity and stability.

As expected, Prabowo thus won with a landslide, gaining 58.6% of the votes:

In the parliamentary elections for the People's Consultative Assembly, Jokowi’s centrist party, PDI-P, received most of the votes, followed by centre-right Golkar and right-wing Gerindra. The Islamist parties PKB, PKS, PAN and PPP received roughly 30% of the votes.

The fact that Prabowo’s party Gerindra only ranked third shows you how much he benefitted from his association with Jokowi. On his own, he would not have won the election.

But as much as Jokowi would like to control Prabowo, his bargaining power will be limited once Prabowo takes over 20 October 2024. Longer-term, it’s clear that Indonesia will be heavily influenced by Prabowo’s own ambitions and ideas.

3. Prabowo Subianto

In his campaign, Prabowo cultivated a lighter touch, for example, by publishing Instagram videos of himself cuddling with a cat and dancing during his political rallies. His social media campaign portrayed him as “gemoy”, a new Indonesian slang word that translates as “supercute” or “cuddly”.

This was a break from his past. Prabowo is a tough man from a military background. He comes from a prominent family that broke with Indonesia’s founding leader Sukarno. Prabowo spent much of his childhood abroad, in Zurich, London, Hong Kong and Kuala Lumpur.

After he returned to Indonesia, he quickly rose through the ranks of dictator Suharto’s military forces and eventually became its commander, helping Suharto maintain control against both internal and external threats.

He married one of Suharto’s daughters in the 1980s and was thought to be Suharto’s natural successor. Though they later divorced, Prabowo maintained his grip over the military.

As a military commander under Suharto, Prabowo’s track record isn’t exactly clean. He was allegedly involved in the kidnapping and likely death of 20 or so pro-democracy students in the run-up to Suharto’s resignation.

Some argue that he engineered riots in 1998 in a bid to take over the leadership after the fall of Suharto. Prabowo was also integral in suppressing dissent in East Timor and Papua. Prabowo denies all of these allegations and has not been formally charged.

After having been pushed out of the army following Suharto’s fall in 1998, he tried to make a comeback by founding the Gerindra party in 2008. He teamed up with established politician Megawati Sukarnoputri to become her Vice President in the 2009 presidential election but lost that election. He lost again in the 2014 election against Jokowi. And in 2019, he surprisingly teamed up with Islamist parties. But failed yet again. Instead, he was chosen by Jokowi to become his defense minister. He finally achieved his dream of becoming president in 2024.

This background makes it clear that Prabowo is an opportunist. He’s power-hungry and feels entitled to his current position. In the coming six months, many analysts believe he’ll be forming a coalition so broad that there practically won’t be any opposition.

He’s seen as a puppet of Jokowi, as he’s vowed to finish Jokowi’s existing policies like moving the capital city to Kalimantan and push for FDI into nickel smelting and other commodity industries. He apparently promised to only control two ministries: defense and oil & gas.

But let’s see how long this situation lasts. Once Prabowo has consolidated power, through legal means or otherwise, I think he will forge his own path.

In his 2015 book The Paradox of Indonesia, Prabowo rhetorically asked why a nation so rich in natural resources had so many poor people. The book argued that Indonesia’s government officials, media, and even religious leaders had become corrupt and that vested interests had taken over the country. He lamented that Indonesia had lost its way after the fall of dictator Suharto.

This language suggests that Prabowo might want to repeat Suharto’s economic agenda of state control and investment-led growth. And that’s probably not long-term bullish for Indonesian equities.

Another worrying sign is that Prabowo has advocated creating a new entity to receive tax revenues outside the finance ministry, equivalent to setting up an Indonesian equivalent to America’s Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The risk here is that it would mean a loss of control for the Ministry of Finance and greater control for himself.

Given Prabowo’s connection to Suharto, the main worry is whether he’ll eventually push for a return to the 1945 constitution, which was in force during the Suharto years of 1966 to 1998. This would essentially abolish elections and reinstate dictatorship.

There is no doubt that Prabowo is about to become a powerful man - it’s only question of how powerful he’ll become. Jokowi seems to be hoping that his son Gibran will become Indonesia’s next president in 2029 or 2034. Other influential politicians like Megawati Sukarnoputri are also likely to oppose any consolidation of power into the hands of Prabowo, providing some checks and balances in the system. For now, at least.

4. Investment implications

4.1. The broad perspective

The broad Indonesian stock index Jakarta Composite had a forceful recovery from COVID-19 with recent enthusiasm for consumer stocks:

Indonesian bank stocks such as Bank Rakyat and Bank Central Asia have done particularly well, with their earnings growth exceeding the rest of the index. Banks now represent almost half of the MSCI Indonesia index ETF.

However, Indonesia’s economic growth has faltered a bit since the initial recovery from COVID-19. After spikes in Indonesian coal and palm oil prices in 2022, they’ve faltered more recently, and this decline has started to trickle down into weaker consumer spending.

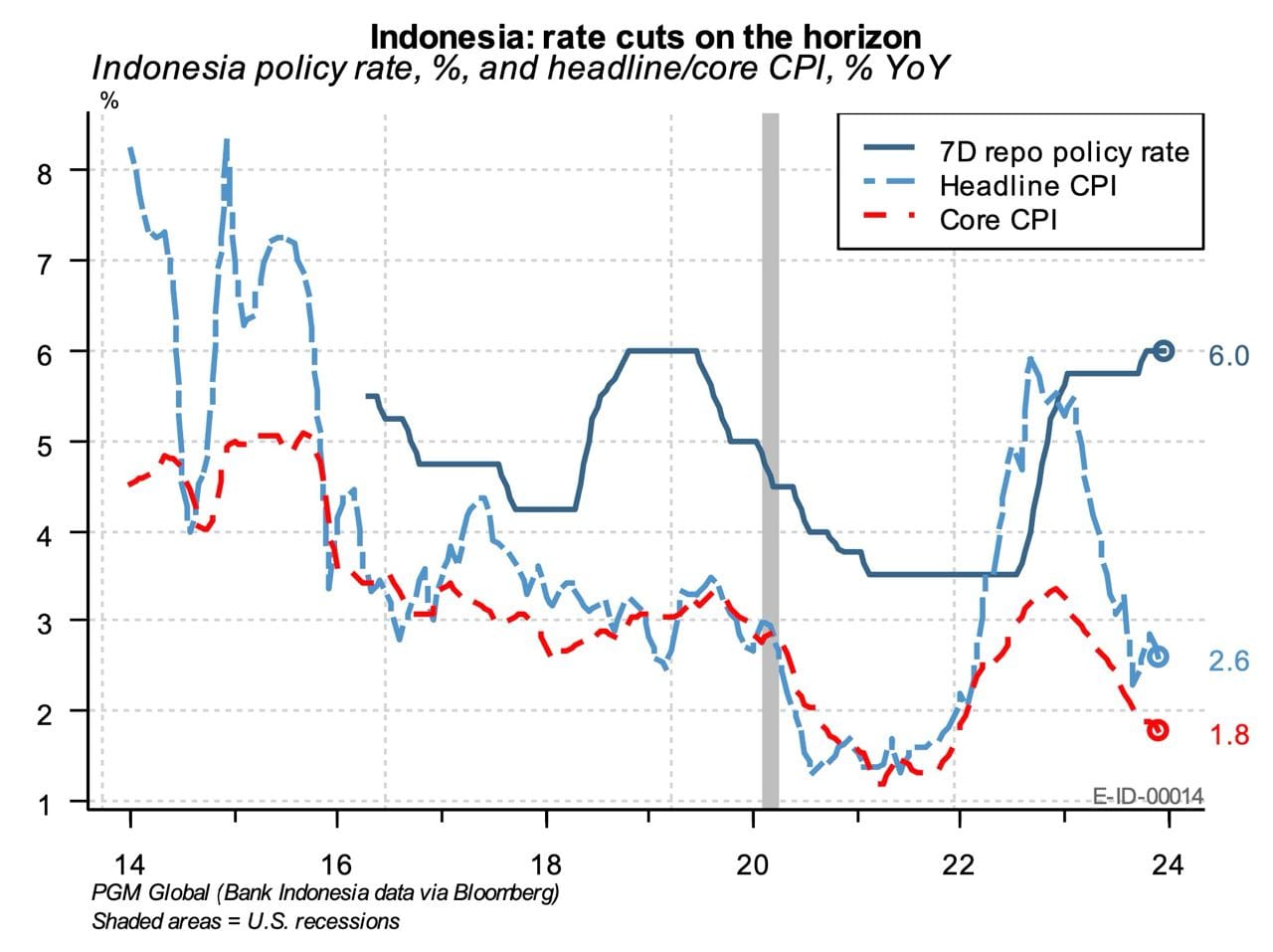

Recent interest rate hikes seem to have been engineered to avoid a depreciation of the Indonesian Rupiah due to high US interest rates and election uncertainty. The inflation rate has already come down to healthy levels. The only reason why Bank Indonesia hasn’t acted yet is because economic growth remains strong at around 5.0%.

There are some signs that households are starting to suffer. Rice, sugar and palm oil prices remain elevated compared to the pre-COVID levels, impacting household consumption. The subsidized fuel price hike in 2022 caused a one-time increase in inflation that also hurt households.

Since early 2022, El Niño weather patterns have also negatively impacted farming, as the limited water supply caused delays in planting. Farm earnings have, therefore, suffered.

Election-related spending might have helped a bit. In a bid to gain popularity, Jokowi sent out 10kg of rice per month to 21 million families in addition to cash handouts, and those have helped on the margin. Bank Mandiri has estimated that such election-related spending has exceeded 1% of GDP, but it’s not clear how much of that spending ended up in ordinary people’s pockets.

So, the economy is somewhat weak, primarily due to a sequential weakness in commodity prices and high interest rates. But foreigners still favor Indonesia as an investment destination, with cumulative foreign net buying back to near the peak, with some selling since August due to election uncertainty:

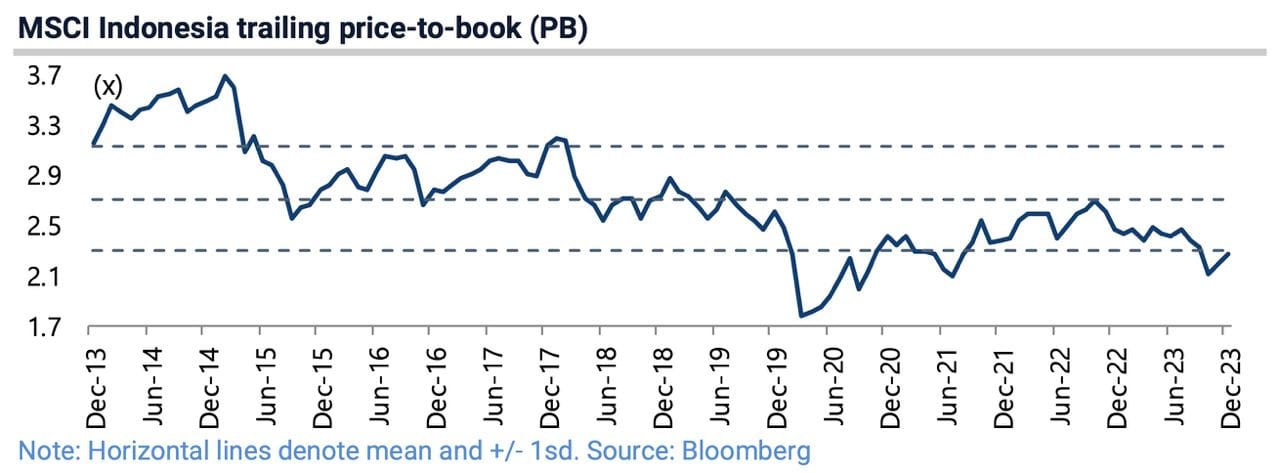

And Indonesian equities remain cheap compared to alternatives such as India. MSCI Indonesia’s Price/Book multiple is now just above 2.0x, a discount to its peak in 2014.

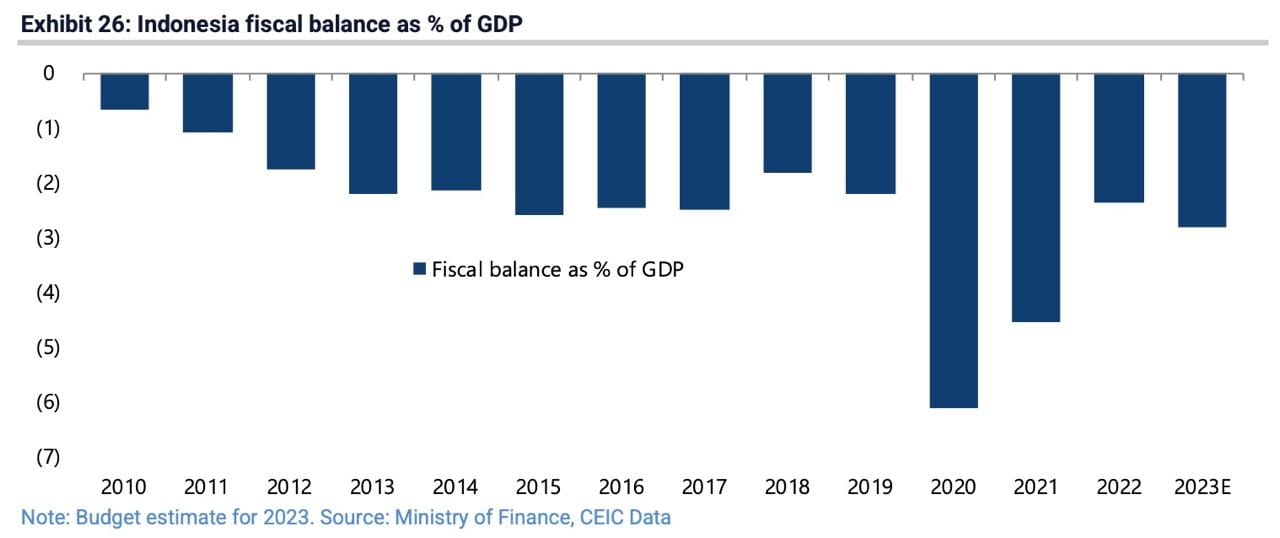

A big question mark for the currency is the likely resignation of conservative finance minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati. Except for a short episode of debt monetization during COVID-19, she built a reputation for fiscal orthodoxy, and it’s unclear who will replace her. Historically, Indonesia’s twin deficits - the current account and the fiscal - have caused the currency to depreciate over time, and I suspect that the Rupiah will probably depreciate under Prabowo.

The big question, of course, is whether Prabowo is serious about his plans to return to Suharto-era economic policies. State ownership and state-led development would be negative for long-term productivity and the health of Indonesia’s private sector. But that’s a longer-term question that probably does not matter much in the short-to-medium term.

4.2. Individual stocks

Let’s discuss how the election might impact the prospects for individual companies.

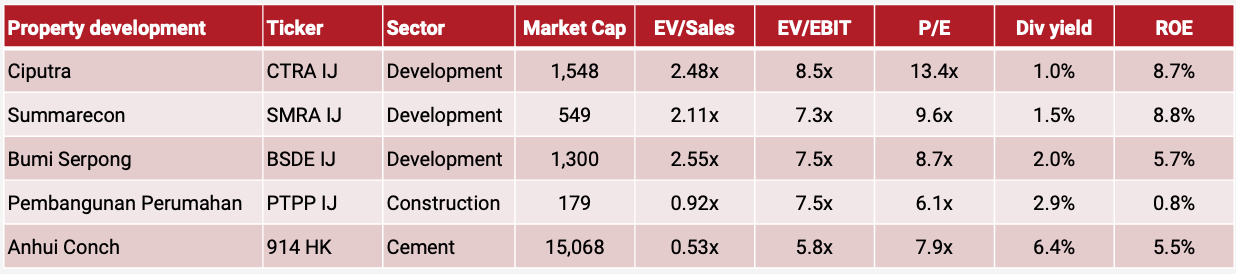

The most obvious beneficiaries of Prabowo’s presidency are the companies involved in the construction of the new capital city, Nusantara, or infrastructure projects. CLSA has previously said that residential property development in Nusantara is going to benefit Ciputra (CTRA IJ - US$1.5 billion), Summarecon (SMRA IJ - US$549 million), and Bumi Serpong (BSDE IJ - US$1.3 billion). State-owned construction companies such as Pembangunan Perumahan (PTPP IJ - US$175 million) might also benefit. From my understanding, though, Indonesian cement companies have limited exposure to Kalimantan, a market that’s instead dominated by Chinese cement producers like Anhui Conch (914 HK - US$15 billion).

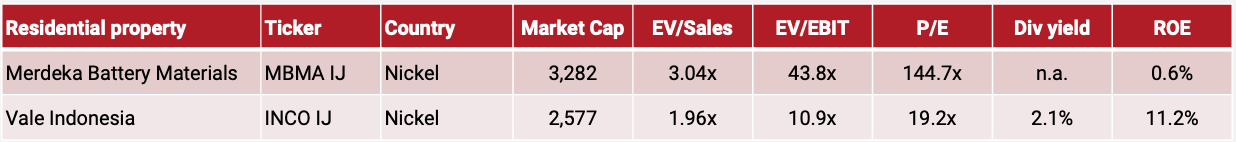

Funders of Probowo’s own campaign include Garibaldi Thohir, who owns Merdeka Battery Materials (MBMA IJ - US$3.3 billion). However, other companies in the EV battery supply chain also stand to benefit, including other nickel miners and processors. Prabowo has pledged to help Indonesia become a high-income economy by 2045 by tapping into Indonesia’s natural resources. So nickel miners such as Vale Indonesia (INCO IJ - US$2.6 billion) should also benefit.

During his campaign, Prabowo promised students free lunch and milk. Dairy companies such as Ultrajaya (ULTJ IJ - US$1.2 billion) and Cisarua Mountain Dairy (CMRY IJ - US$2.4 billion) should stand to benefit, though the impact of the program on their businesses will probably be small.

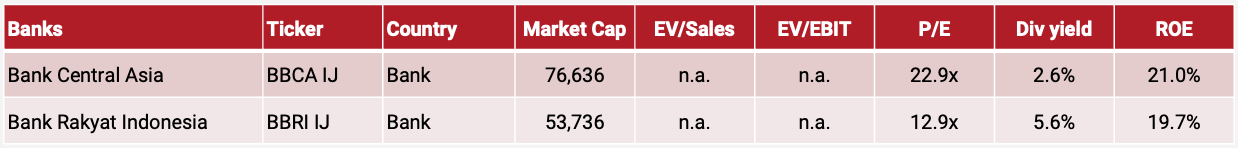

Finally, Prabowo has said he’s comfortable with a higher debt/GDP ratio. That seems to imply greater budget deficits and higher credit growth. The system-wide loan-to-deposit ratio is only 85% so there’s definitely room for growth. Banks such as Bank Central Asia (BBCA IJ - US$77 billion) - and Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BBRI IJ - US$54 billion) would benefit from higher credit growth, though also face the headwind of lower interest rates in the near term.

Gun to my head, I would probably buy a dairy company like Ultrajaya or a bank like Bank Rakyat, given their superior return on equity.

When doing the research for this post, I feared that Prabowo’s involvement with Islamic parties in the 2019 election might mean that he would want to introduce a ban on the sales of alcohol. But Prabowo is not a conservative Muslim and is unlikely to push this agenda. While Islamic parties now control 30% of the parliament and PPP / PKS / PAN combined less than 20%, they won’t gather enough votes to make it happen. Neither of the major parties in Prabowo’s current coalition supports a full alcohol ban.

5. Conclusion

I see Prabowo as a similar man to Xi Jinping, who was initially seen as a reformist and pro-business. The big question is whether checks and balances in the political system can stop Prabowo from consolidating his power. As a former military commander, I think he’s primarily driven by power rather than ideology.

In the short-to-medium term, I don’t think Prabowo’s ascent is going to matter much at all. Prabowo says he’s comfortable with a greater debt/GDP ratio, and it seems plausible to me that credit growth will accelerate, benefitting banks. On the other hand, I think interest rates are going to come down again in the next 1-2 years, causing net interest margins to compress.

I also believe that greater fiscal deficits and a step away from the fiscal orthodoxy of current finance minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati is going to cause weakness in the Indonesian Rupiah.

But other than that, Indonesia will keep growing steadily. There are always opportunities in any political system that’s pro-business and reasonably stable.