Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may from time to time have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is disclosure and not a recommendation to buy or sell.

Executive summary

The toll road sector is tricky to invest in, given often heavy-handed government policies in countries such as China and Indonesia. Concessions have a limited life span. But thanks to the ongoing pandemic, stock prices in the sector have come down and today might represent a decent entry point.

I believe that you’ll want to avoid most of China’s listed toll road operators, despite their low valuation multiples. Their concessions typically end around 2030, in less than a decade from today. And the country’s road network is already built out, so there is no scarcity factor to speak of. An exception is Yuexiu Transport, which offers an 11% dividend yield and a weighted average concession maturity of 2037.

I see significantly more opportunities in Indonesia. Traffic volumes are rising on a secular basis. Road infrastructure has been dilapidated. State-owned Citra Marga looks particularly attractive to me. Another stock that I find compelling is WCE Holdings, which is in the process of completing Malaysia’s West Coast Expressway in 2022. Insiders in WCE Holdings have been buying shares throughout 2021.

Introduction

There’s a case to be made for buying toll roads in the midst of the pandemic.

Toll roads don’t have many fixed costs, so they are unlikely to end up cash-flow negative during a downturn. And thanks to rising traffic volumes across most Asian countries, toll road operators tend to be secular growers.

Those are the key reasons why I’m attracted to the sector. I will go through the basics of toll road investing and then discuss the listed stocks that I have identified.

The toll road business model

Toll road concessions are great assets, in theory. Margins on incremental traffic volumes are close to 100% making them great compounders in environments of rising traffic.

Initial construction capex tends to be massive and front-loaded. Once the toll road becomes operational, capex is usually amortised over the remainder of the concession. With low periodic maintenance costs (typically ~2% of revenues per year), underlying free cash flows can often greatly exceed the reported net profit. That’s especially true given that taxes often take the full depreciation into account.

But on the other hand, concessions tend to end within a short period of time. At the end of the contract, the asset is typically handed back to the government with no terminal value. In some cases, concessions might be extended. Either way, I believe that the EV/EBITDA multiple you should be willing to pay is inversely related to the remaining length of the concession. Here is a rule of thumb for “fair value” EV/EBITDA multiples depending on the remaining concession length:

Every concession agreement sets out how tolls will increase over time. There’s typically an inflation adjustment factor based on a consumer price inflation index. So they are in theory hedged from inflation - but only if you believe that CPI accurately tracks inflation. Concession agreements often also allow tolls to increase in real terms as well. It all depends on how the concession contract is designed.

In listed Asian toll roads, the operator typically takes on traffic risk. This implies that it will make more money if volumes rise and vice versa. Given the traffic risk, greenfield projects imply significant risk to the developer. A study by Muller (1996) suggested that developers often misjudge the amount of traffic that the toll road will enjoy subsequent to completion. For 10 out of 14 toll roads, actual revenues on average differed from the original forecast by 20-75% - and almost all of them were overly optimistic. So be very careful with new toll road developments.

To mitigate the risk, governments sometimes step in with minimum revenue guarantees or availability payments, whereby the operator receives fixed amounts subject to certain performance obligations.

Many toll roads enjoy underlying secular traffic volume growth. Such tailwinds can come from population growth, higher car and truck penetration rates per capita or from a ramp-up in traffic on a new toll road.

The main substitutes are public roads as well as rail and air travel. In China, for example, the Ministry of Railways has been building out a high-speed railway network, taking passengers from the competing toll roads. And in some cases highly developed areas such as Shenzhen, there might be several toll roads competing for the same business.

Given a certain level of EBITDA at maturity, it also matters what the company does with the cash flows it generates. Reinvestment opportunities in existing toll roads tend to be limited so it’s standard for listed toll road operators to pay out a high percentage of their cash flows as dividends. In the listed universe, there are many cases of malinvestment in unrelated areas such as property development or financial speculation.

Debt is almost always required for a toll road to be built. Debt is usually sculpted in such a way that the debt service coverage ratio (DSCR) exceeds 1.25x with a decent margin of safety. In regions where the liquidity of local debt markets is not deep enough, toll road operators may be forced to borrow in US Dollar, which would then introduce a currency mismatch. Governments can help alleviate this problem through shadow tolls. Either way, currency mismatches is something to keep an eye out for.

To summarise, I believe that the ideal situation is when a listed toll road has the following characteristics:

The remaining concession length is long

Low EV/EBITDA

The toll road has just started to break even

Traffic has yet to fully ramp up

Debt service coverage ratios >> 1.25x

No major currency mismatches

Rational capital allocation from the point of view of minority shareholders

In my view, the factors that are especially important are a long remaining concession length, low EV/EBITDA and careful capital allocation.

Regional comparison

Passenger car volumes tend to exceed truck volumes. So growth in passenger car traffic volumes will be the key indicator to forecast.

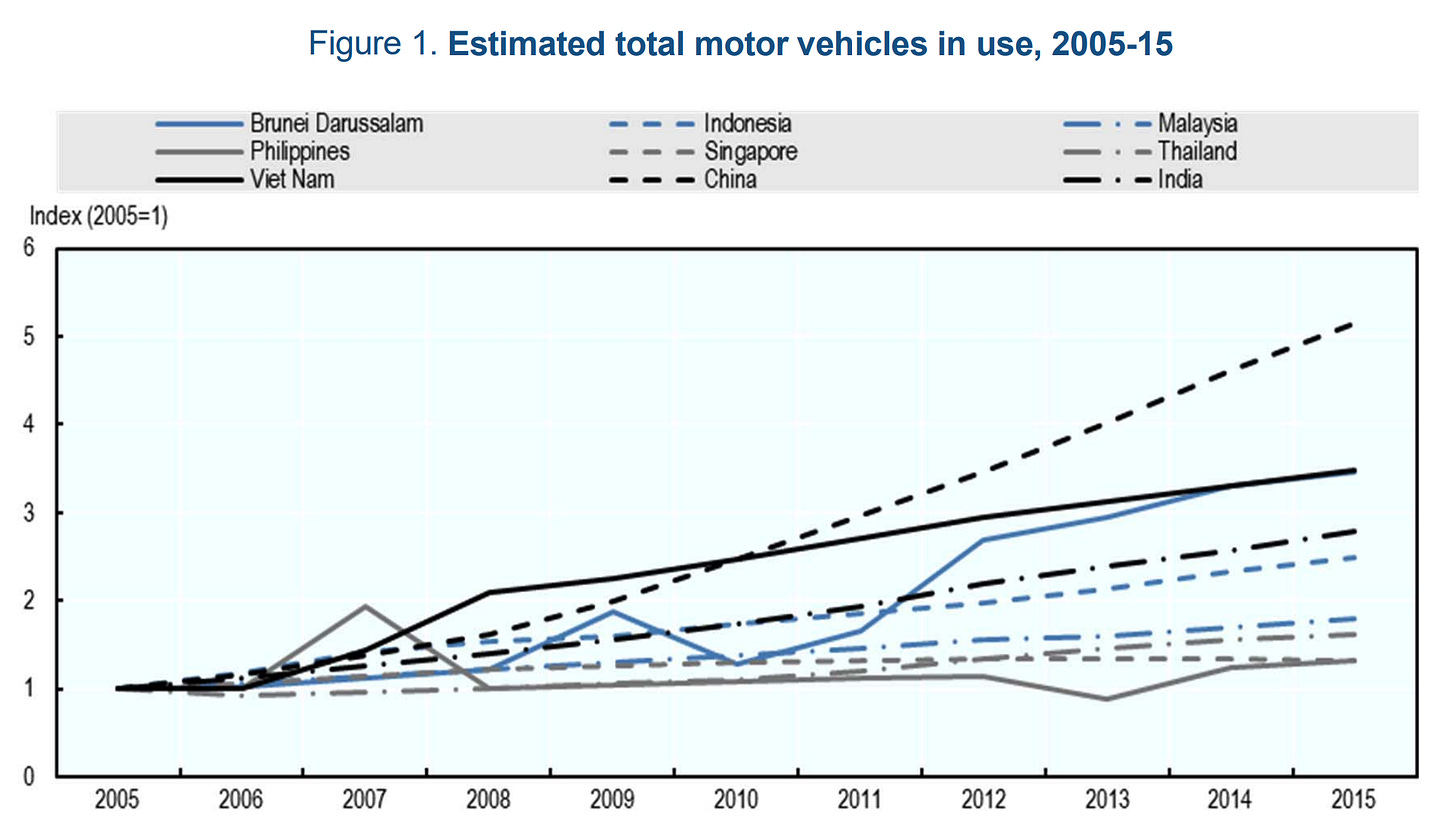

China’s car ownership per 1000 people is today around 200, similar to that in Thailand and slightly lower than that in Malaysia. While this car penetration rate is much lower than Europe’s 500-600, the purchasing power of consumers is also much lower. I see much greater upside in the car ownership rates of Vietnam, India and Indonesia.

The growth in motor vehicle use was the highest in China over the 2005-2015 time frame, followed by Vietnam, India and Indonesia.

China’s infrastructure investment/GDP has topped global charts for well over a decade.

That has led to a very competitive infrastructure that compares favourably even to developed markets. Vietnam and Indonesia lag far behind.

As a toll road operator, you’ll want the country’s infrastructure to be as dilapidated as possible as it increases the scarcity of your assets. For that reason, toll road assets in Vietnam and Indonesia appear much more attractive than in say China.

Toll road industry map

China has a large number of listed toll road operators, including China Merchants Expressway, Jiangsu Expressway and Zhejiang Expressway. In this article, I will focus on the Hong Kong-listed entities as they tend to be cheaper than their A-share counterparts and also accessible by foreign investors.

Southeast Asia also has a few listed toll roads, most notably Bangkok Expressway in Thailand and state-owned enterprise Jasa Marga in Indonesia.

China

China had over 200,000 km of expressways at the end of 2019 if you include the expressways owned by local governments. This compares to around 98,000 km of expressways in the United States. And the pace of construction keeps accelerating. Expressways under the purview of the central government are currently around 110,000 and there are to increase this number by an additional +50%.

Government policies in China are set by Soviet-style 5-year plans. Each government agency is then tasked to achieve the targets set in the document. One such target is the length of the country’s highway network.

The problem for minority investors is that most toll road operators in China are controlled by the government (typically local). And they are often used for political purposes, including achieving objectives such as the length of the national highway network.

The government is also keen to lower tolls for consumers. One peculiarity about Chinese toll roads is that the military and police vehicles can use expressways for free. Tolls are also waived during national holidays such as the Lunar New Year. During COVID-19, the government froze all tolls across the country, causing a heavy drop in revenues for China’s listed toll road operators. They are now again free to collect tolls from drivers, but this event does highlight the weak bargaining power they have against the government.

One consequence of excess construction of highways is a rapid build-up of debt. In 2019, toll revenue for the country as a whole reached close to CNY 600 billion compared to debt servicing costs of CNY 840 billion. And that’s before paying any maintenance. It’s an unsustainable situation that’s about to become even more unsustainable.

Another factor worth taking into consideration is the remaining lengths of China’s toll road concessions. According to Chinese law, toll road concessions cannot exceed 30 years. Most of the concessions were granted in the late 1990s onwards in a bid to improve SOE profitability and help finance the country’s ambitious road-building program.

Here are the main listed toll road operators in the country:

Jiangsu Expressway (177 HK) runs the Shanghai-Nanjing Expressway (50% of revenues), Xicheng Expressway, Guangjing Expressway and the Nanjing section of the Nanjing Lianyungang Expressway and several others, all located in China’s Jiangsu province. It also operates gas stations and leases properties along its toll roads. The weighted average concession maturity is 2032. In other words, the concessions will have to be handed back to the government in roughly 10 years time.

Zhejiang Expressway (576 HK) runs the Shanghai-Hangzhou-Ningbo Expressway, the Shangsan Expressway and the Ningbo-Jinhua Expressway and several others. Its concessions will expire in 2031, on average. But close to half of profits comes from Zhejiang Expressways’s “securities segment”, which is a retail brokerage operation called Zheshang Securities, connected to controversial Zheshang Bank. Tolls were shut early on during the pandemic but are now open again. The company also owns two hotels (Zhejiang Grand Hotel and Grand New Century Hotel).

Shenzhen Expressway (548 HK) runs 16 toll roads around Shenzhen and surrounding areas in the Guangdong Province of China. It should be seen as a pure-play with 90% of revenues from toll roads, with the remainder from property development and a Chongqing waste & sewage company called Derun Environment. Some of Shenzhen Expressway’s most important toll roads include Meiguan Expressway, Jihe Expressway, Shuiguan Expressway and the Outer Ring Project. One of the major growth drivers for Shenzhen Expressway is the expansion of Jihe Expressway that connects Shenzhen International Airport to the Shenzhen district of He’ao. The weighted average concession maturity is 2031.

Anhui Expressway (995 HK) operates 5 toll roads in the Anhui Province of China, including the Hening Expressway, the Gaojie Expressway Xuanguang Expressway, the Lianhuo Expressway and the New Tianchang Section of the National Trunk 205. Most of these toll roads are majority-owned, but also have minority interests in them. The weighted average concession maturity is 2035. Anhui Expressway apparently also offers pawn shops. The company is dual-listed in Hong Kong and Shanghai.

Sichuan Expressway (107 HK) is another dual-listed toll road operator managing the Chengdu-Chongqing railway, as well as another toll road in the Sichuan Province. It’s almost entirely engaged in the toll road business as well as ancillary services such as petrol stations. The weighted average concession maturity is 2031.

Yuexiu Transport Infrastructure (1052 HK) is part of Yuexiu Holdings and has roots in Guangdong. It has a total of 15 investments across China, mostly in Guangdong and Hubei Province. The remaining concession length is longer than that of Zhejiang Expressway and Shenzhen Expressway with a weighted average maturity of 2037.

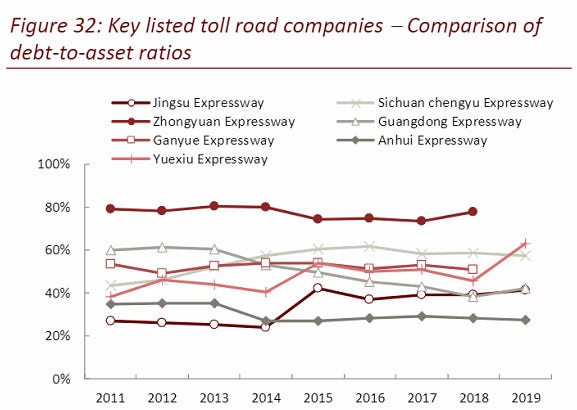

China’s listed toll road operators enjoy low valuation multiples. But note that the remaining concession length is typically only 10 years. And as a minority shareholder, you are pretty much at odds with government interests, so the risks are high.

If you forced me to choose one of them, I would probably lean towards Yuexiu Transport. It has a diversified portfolio of toll road assets, many of which are in Guangdong - one of China’s economically more dynamic provinces. Yuexiu has the longest remaining concession length of 16 years. With an 11% dividend yield, I believe that there is a good chance you’ll get back your money and more.

There are also a few listed toll road operators in the A-share market and some of them can be accessed via HK-Shanghai or HK-Shenzhen Connect, most notably China Merchants Expressway, Guangdong Provincial B-share and Henan Zhongyuan. I have not included them in the above analysis as I believe that the Hong Kong-listed companies trade at much more attractive multiples.

It’s also worth mentioning that several of the listed Chinese toll roads are dual-listed and trade at a lower level in Hong Kong than on the mainland, including:

Jiangsu Expressway (the H-share trades at a 22% discount to the A-share)

Shenzhen Expressway (the H-share trades at a 31% discount to the A-share)

Anhui Expressway (the H-share trades at a 36% discount to the A-share)

Sichuan Expressway (the H-share trades at a 53% discount to the A-share)

But as China’s capital account is closed and short-selling of individual stocks is illegal on the mainland, there is no reason to think that the discounts will necessarily narrow.

Thailand

Thailand is a relatively mature market for toll roads. There is underlying volume growth with the number of registered cars growing in the low single digits.

Traffic in Bangkok is down quite a bit since early 2020 due the ongoing pandemic with the Delta variant of SARS-Cov-2 recently hitting Thailand hard.

Bangkok Expressway and Metro (BEM TB) is a Thai toll road operator run by the Trivisvavet family, which also owns Thai Tap Water and construction company CH Karnchang. Bangkok Expressway runs three toll roads and metro lines in Bangkok and surrounding areas. Toll roads make up the majority of revenue at around 64%, followed by 31% rail (metro lines) where it is one of Bangkok’s two key mass transit operators. Two of the toll road concessions end in 2035 and the remaining one in 2042. There have been related party acquisitions in the past, but typically at fair values.

Don Muang Tollway (DMT TB) is the operator of the toll road between Din Daeng District - Anusornsathan in the northern part of Bangkok, connecting the city with Don Muang Airport and Don Muang Railway Station. In the future, the tollway section will become a part of Motorway number 5, connecting Bang-Pa-in to Mae Sai. The company’s concession lasts until 2034. Bangkok’s new red mass transit line is located along the Don Muang Tollway and will open in November 2021. This presents a major risk to the company.

Bangkok Expressway looks overpriced. Don Muang Tollway seems inexpensive on 2022 consensus EBITDA but with the red line opening soon, I don’t think it’s a no-brainer.

Malaysia

Toll roads were introduced in Malaysia in the 1960s and have become prevalent across the country since then. Over the past decade, the political landscape for private toll roads has become more fraught with risks. The previous government wanted to nationalise all highways and abolish tolls. The current government is suggesting extending concession lengths in exchange for lower tolls.

Traffic in Kuala Lumpur is down quite a bit since early 2020.

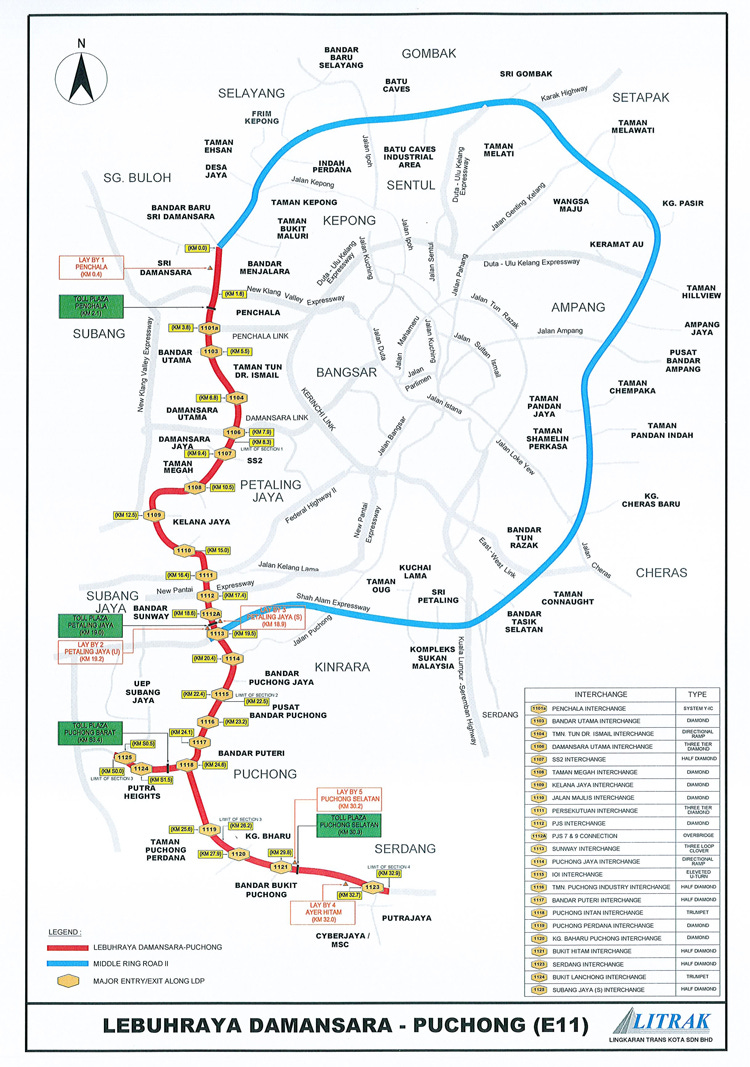

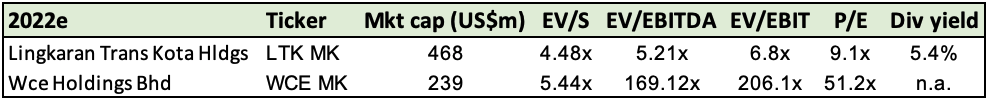

Lingkaran Trans Kota (LTK MK) is the highway concessionaire that runs the Klang Valley expressways Damansara-Puchong as well as Western Kuala Lumpur Traffic Dispersal Scheme (SPRINT Highway). The controlling shareholder is Gamuda Group. The two concessions run until 2030-2034. In June 2019, the government sent them a letter of offer to acquire both of the concessions. It’s still not clear if the sale will go ahead and at what price.

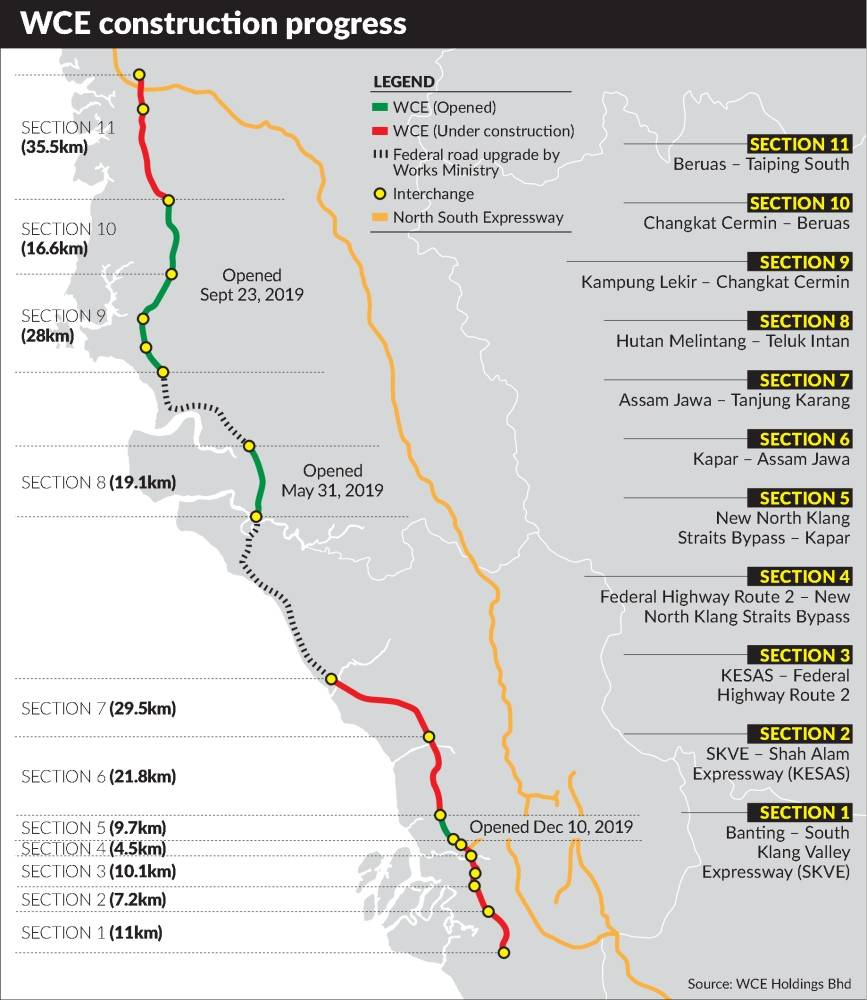

WCE Holdings (WCE MK) is building the 233km West Coast Expressway from Banting in Selangor to Saiping in Perak through a 80% owned subsidiary. The parent company is IJM. The completion of the project is only at around 63%, so expect revenues to grow going forward. The concession runs until 2065, so an additional 44 years. Management believe it to be unlikely that the government would seek to buy back the West Coast Expressway. And even if they do, there are allegedly clauses in the concession agreement to protect WCE shareholders.

I think Lingkaran Trans Kota is uninvestable despite the low multiple. Who knows whether the government will offer a fair price for the company’s two concessions. WCE Holdings could in theory be compelling given that the West Coast Highway is due for completion in 2022. It is a significant asset with a long remaining concession life. Insider buying in the company has been high throughout 2021.

Indonesia

The first Indonesian toll road was created by the Indonesian government in 1978 and government company Jasa Marga was assigned the role to operate it. From 1987 onwards, private sector companies were invited to participate in toll road development hand-in-hand with Jasa Marga under BOT (build-operate-transfer) contracts. That put Jasa Marga in an awkward position of being both the toll road authority as well as an operator in competition with private sector companies.

From 2004 onwards, Jasa Marga returned the authority function to the Toll Road Regulatory Agency under the Ministry of Public Works. And so today, Jasa Marga should be seen as a pure-play toll road operator.

Since Joko Widodo (“Jokowi”) became Indonesia’s President in 2014, the pace of toll road construction has picked up pace significantly. Indonesia’s transport infrastructure is notoriously poor and his campaign to improve the road network has yielded benefits. From 2015 to 2018, the Jokowi administration built 718 km of new toll roads, compared to 229 km during the previous 10 years. The Trans Java Toll Road is now complete, for example, helping reduce the travel time between Jakarta and Semarang from 12 hours to just six.

But with a strained national budget, much of the burden on building toll roads has fallen on state-owned enterprises who have increased their capex significantly. In return, they have received long-lasting 30-40 year concessions. Due to bottlenecks in land acquisition, private companies have not been able to fully participate. So most of the development has been led by state-owned enterprises who have relied on the legal authority of Law 2 of 2012 on Land Acquisition, which sped up the process of acquiring land for them.

Road traffic in Jakarta remains relatively strong, despite Indonesia’s second wave of COVID-19. The country has not experienced the type of long-term lockdowns as seen in Thailand or Malaysia.

Here are the largest companies operating in Indonesia’s toll road sector today:

State-owned Jasa Marga has a close to 50% market share of toll road operators in Indonesia

Hutama Karya is a state-owned enterprise with a 23% market share

Waskita Karya is a state-owned enterprise with an 11% market share that’s over-indebted and just received a state bail-out a few months ago

Astra Tol Nusantara is a private company, owned by Scottish-owned conglomerate Jardine Matheson and has a 10% market share

Listed state-owned enterprise Citra Marga Nusaphala with a 3% market share

Listed private company Nusantara Infrastructure with a 1% market share. It is a listed subsidiary of Philippine conglomerate Metro Pacific

Former toll road authority Jasa Marga (JSMR IJ) is today a full-fledged state-owned toll road operator. Most of the company’s toll road assets are on Java, especially in the area around Jakarta. But there are also a few scattered toll roads on Sumatra, Bali, Sulawesi and Kalimantan. The weighted average concession ending date is 2050.

Another listed company is Citra Marga Nusaphala (CMNP IJ) currently has six toll road concessions, all of them on Java with a weighted average concession maturity of 2056.

Nusantara Infrastructure (META IJ) owns a controlling stake in toll road operator Margautama Nusantara as well as Pettarani Toll Road at Makassar, which is at 40% to completion. The toll road concessions run until 2039, on average. It also owns a Hydro Power Plant in Northern Sumatra.

My biggest problem with Jasa Marga is the company’s debt levels at 250% of revenues. Since borrowing costs have been about 8% historically, they could be on the hook of 20% of revenues in interest expense. The company’s EV/EBITDA multiple of 10x looks attractive though. State-owned competitor Citra Marga enjoys lower debt levels. EV/EBITDA could reach 9x if the company returns to pre-pandemic profitability. For a company with 35 years left on its concessions in a country with fast-growing traffic, that seems like a good deal to me.

Final conclusion

Investing in toll roads requires heavy number crunching and I have not yet built any financial models on any of the above stocks. The remaining concession length, the potential for higher traffic volumes and government interference will be key factors to take into account.

WCE Holdings seems to hold the most promise to me in the near term as it becomes a concession holder of Malaysia’s West Coast Highway. One would have to become comfortable with the politics surrounding Malaysian toll roads, however. Yuexiu Transport and Citra Marga also appear to be undervalued given underlying traffic volume growth and remaining concession lengths.