Table of Contents

Robert Kuok’s first memory was his mother leaving him when he was 1.5 years old. He tensed up, cried and remembers feeling heartbroken. In the next year, he and his brother would hide underneath tables and chairs - as if those were the only places they could feel safe.

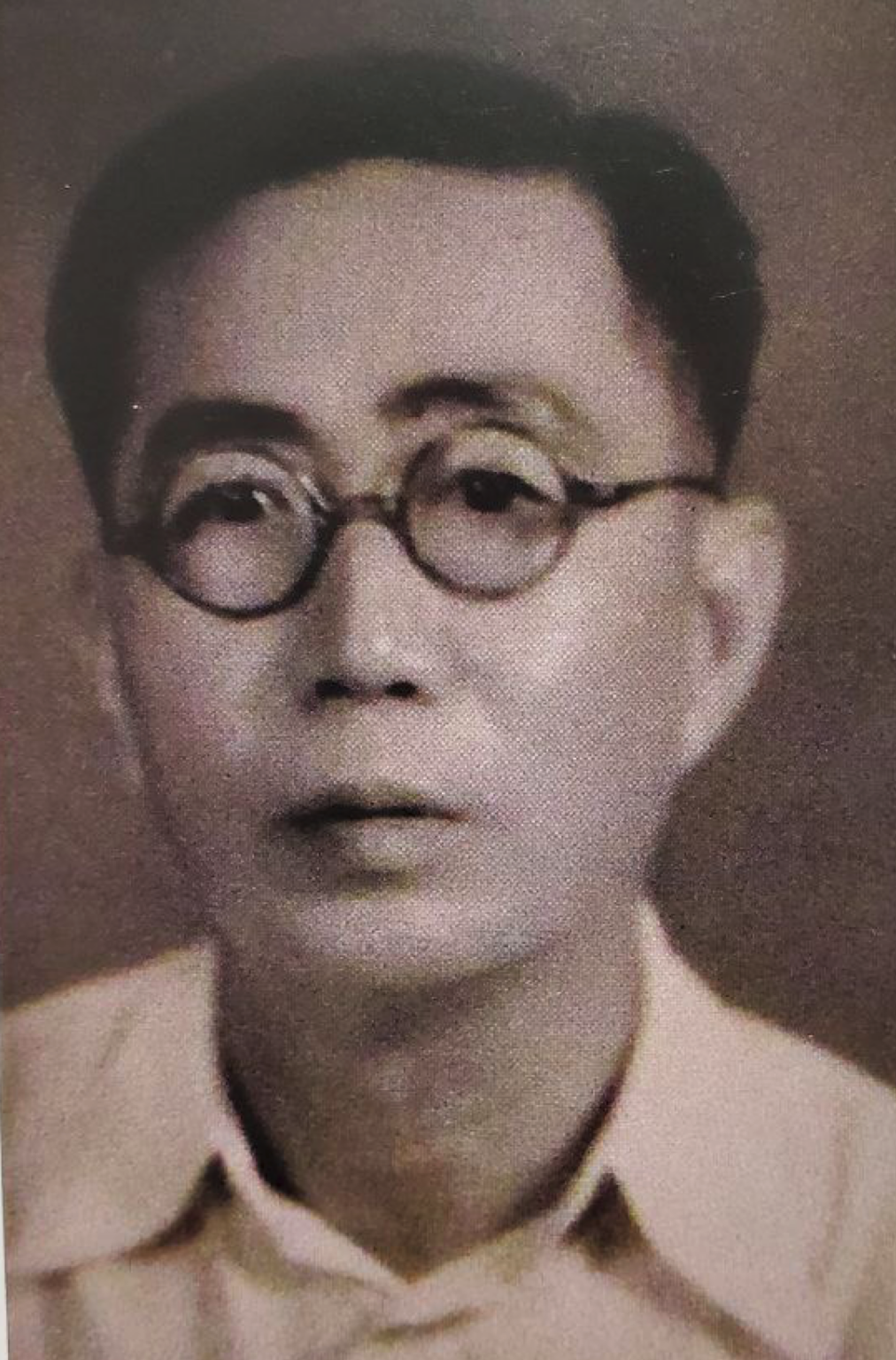

His parents’ marriage was tumultuous. His father was a womaniser, a gambler and an opium addict and mistreated her constantly. So going back to China provided an escape for her.

In 1925, his mother finally came back again. But while the marriage stayed intact for many years, the household went from crisis to crisis. Little Robert had to adapt by growing up faster than most other children.

His father was a born trader. He had social skills and made friends with Malay civil servants in the government, making a variety of deals that would help his family survive. His big break came in the 1920s, serving as a contractor under the English colonial system.

Then the Great Depression came. There was never enough money, and Robert’s mother had to figure out ways to make the money last, including finishing every grain of rice in the bowl. Nothing was to be wasted. And meat was a luxury. The malnourishment caused Robert to weigh just 45kg, even in his teenage years.

To add fuel to the fire, Robert’s father eventually fell in love with a young woman who became his second wife. It wasn’t unusual in colonial Malaya to do so, but it did provide further hardship for Robert. Whatever money he made now flowed to the new wife and her new family.

Looking back, Robert thinks that those early years of financial misery and deprivation drove him on later in life.

Life in colonial Malaya

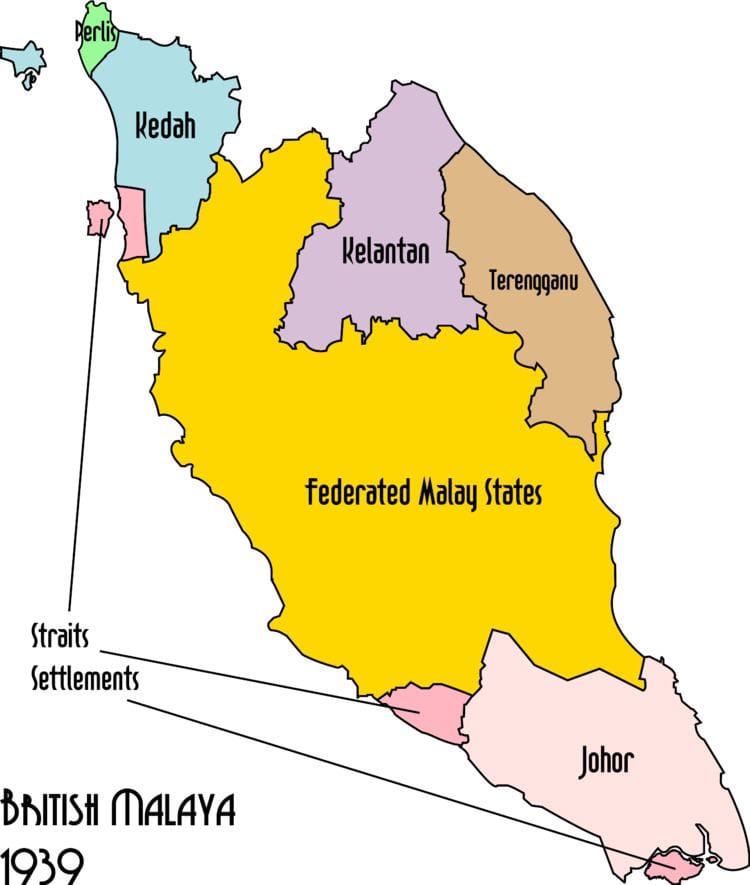

Robert’s father had always admired the British colonial administration. They brought law and order and created basic infrastructure. But Robert always felt they were racist, arrogant and patronising.

He was not a star student. Still, through his father’s help, he managed to get into Raffles College in Singapore, where he got to know many of the future leaders of Malaysia and Singapore, including Abdul Razak and Lee Kuan Yew (who was one year ahead of him). Those contacts would prove to be valuable later on in his life.

His stay at Raffles College was cut short by the war. In 1941 bombs exploded across Singapore when Japanese forces attacked. He knew that the British wouldn’t stand a chance. The Japanese were brutal in how they treated their victims during the war. He remembers seeing people’s heads cut off, then hanging them on lampposts as warnings for anyone who dared oppose them. The Chinese were treated the worst of all.

The Kuoks felt they had to leave the city. Through family friends, they managed to escape to a pineapple farm in Johor. Whenever soldiers came by they pretended to be peasant workers, wearing drab clothes to avoid attracting attention. Surprisingly though, even though this was a time of peril, looking back Robert felt that this was one of the happiest memories of his life because he felt he was on an adventure and he was united together with his family.

His first success in business

Later on, the family was compelled to cooperate with the Japanese. You either took a job as a clerk or stayed at home and were suspected of being anti-Japanese.

So Robert’s father sent him to work as an assistant at Mitsubishi Trading in Johor Bahru. That way he could at least make some money for the family. It was an invaluable experience for both Robert and the family. He became the first employee of Mitsubishi Trading in Johor Bahru at age 19 and after a few years, he would have several employees under him.

Mitsubishi’s branch office in Singapore was highly profitable. The Japanese Military Administration had given Mitsubishi a monopoly on importing and supplying rice and cigarettes to Malaya and Robert was right in the middle of that trade.

And there were opportunities to make money on the side. Through his social skills, he made friends all around Singapore and co-operated with them in his quest to make money. He would team up with purchasers of rice and give them extra-large allocations, then sharing the profits together with them. It was a form of corruption, of black marketeering. He didn’t mind. He was so young that the risk of getting caught didn’t cross his mind.

That was the start of his first fortune. He amassed millions of so-called “banana money” - the currency used during occupation. Unfortunately, the value of the currency declined through the end of the war as money printing was used to finance the war effort. And Robert lost most of the money he had made through those highly profitable side businesses.

Laid-off from Mitsubishi

Mitsubishi’s business in Singapore went away after the war. And Robert lost his lucrative position as a trading assistant. In Singapore, the Japanese banana money became worthless and everyone had to start from scratch.

He managed to make one last deal. His Japanese boss offered him 200-300 bales of cigarette paper straight from Japan that he could pay for with useless banana currency. He made $400,000 on that single transaction and accumulated capital in an environment where capital was becoming increasingly scarce.

Once the British came back, those lucrative government concessions were once again given to British firms such as Boustead, Guthrie and Sime Darby. His father did manage to get one contract with the British Military Administration in 1945 to collect fruits and vegetables and deliver them to Japanese prisoners of war - but that would prove to be the great deal his father managed to make.

Kuok Brothers Limited

His father finally passed away in 1948. His children were now on their own and decided to continue their father’s business under a new company banned: Kuok Brothers Limited.

Even though Robert was young, he became an acting CEO. It was obvious from the start that he had ambition and talent. As he himself noted:

“I knew that I had what was needed to be a businessman, like a duck taking to water. I am a very focused person. When I do something, I want to do it well.”

Their first problem was how to fund their working capital. The British banks practised blatant discrimination and refused to lend to any local firms. He was furious at the racism underlying colonial Singapore and vowed to survive without the help of Hongkong Bank or the other Western banks operating in Singapore.

It wasn’t until the now-famous banker Chin Sophonpanich of Bangkok Bank came to Singapore that the business took off. Chin was a Teochew Chinese and embraced them with open arms. Within an hour of stepping into their office in Singapore, he offered the Kuok Brothers letters of credit and banker’s acceptances worth tens of millions of dollars.

The last days of the British empire

In the 1950s, Britain slowly lost control over its colonies. And new opportunities emerged for local firms. Chinese groups such as the Hakkas, Teochews and Fujian people who controlled trade throughout Southeast Asia capitalised on the opportunity by lobbying for new government contracts.

During the colonial era, British manufactured goods enjoyed preferential tariffs. But when the British empire was dismantled, many of those proud British manufacturers went belly up and a host of local companies suddenly fought to fill the void.

The Kuok Brothers set up an office at Cecil Street in Singapore, continuing to focus on government contracts for key commodities such as rice, sugar and wheat flour.

In the beginning, they were simply distributors. They bought wheat from Sime Darby and distributed it to the Johor market, for which they managed to get an exclusivity contract.

A big break came in 1952. The Federal Malayan government called for a tender for the government rice agency. The job was to receive rice from overseas, store it in warehouses owned by the government and transport it to the southern half of the Malay Peninsula.

People thought Robert was crazy for even trying. No local company had ever put in a bid. But he argued that their track record was just as good as anybody else’s and they finally won the contract to become rice agents for the Malayan Government in Singapore. It wasn’t lucrative but they were dealing in high volumes.

He became an expert on rice. He travelled frequently to Bangkok and developed personal ties to exporters, learning everything from scratch.

During those early years, he worked hard as hell. While most other businessmen in the region attended hostess bars and gambled, he shunned such activities instead worked a minimum of 12 hours a day, every day of the week.

Eventually, he became frustrated with the rice trade. Rice didn’t experience wild price swings, so margins remained low. And the barriers to entry were non-existent, causing intense competition.

Getting a taste for sugar

He felt sugar could become a much more profitable commodity for them to trade. It’s a highly sought-after commodity, so when there is no supply, the commodity can rise to almost any price. That’s exactly what he was looking for: capped downside and potentially unlimited upside.

It was a difficult industry to break into. All imports into Malaya were controlled by the European “hongs” (trading houses) in Singapore. Just like with rice, Kuok started buying sugar from the British and distributing it. British firm Guthrie offered to distribute sugar for Taikoo Sugar in Johor Bahru - just 80 tons a month. Trucks were sent daily from the dingy warehouses along Boat Quay on the Singapore River over to Johor Bahru, just north of Singapore.

It was during this time that he got in touch with a Mainland Chinese man called Lim Kai. That man worked for the People Republic of China’s state-owned enterprise COFCO (China Cereals, Oils and Foodstuffs Corp). Mainland Chinese traders were not allowed to visit Malaysia or Singapore. That gave Robert a unique position as a middle-man exported from Southeast Asia to Communist China, taking a nice cut in the process. Robert eventually even formed a relationship with Communist China’s version of the CIA - the Ministry of Public Security - acting as a middle man in political matters between Malaysia and the PRC.

He also found out he could compete with Guthrie and the other British hongs by importing sugar directly from India, which enjoyed preferential import duties thanks to its connection with the British Commonwealth. That started to make him real profits.

The real break came with Japanese trading partner Mitsui. The Japanese asked if Kuok wanted to become a partner in a sugar refinery project. It’s not clear why the Japanese felt they needed Kuok, but he proved to be invaluable in securing concessions from the government.

He wanted the sugar refinery to enjoy full tariff protection and ban all imports of refined sugar. This was a tall order. But Robert benefitted from a change in the political landscape: Malaysia became an independent nation in 1957 and he had become friends with the new Minister of Commerce Khir Johari. It was through this contact that Robert basically secured a monopoly on refined sugar in the new nation of Malaysia.

Even though the Kuok Brothers were only a minority partner in the project, Robert managed to gain bargaining power against his Japanese friends. Khir Johari managed to make it such that the government had to approve every single foreign partner for the refinery project. That provided bargaining power for the Kuoks in securing a better deal in the refinery project.

And not only that - but Kuok also controlled the supply of raw materials and distribution of refined sugar, enabling him to make money all across the supply chain. It proved to be yet another of his side deals that served him well throughout his career.

It wasn’t just tariff protection that enabled Kuok to become rich. He was also a skilled operator, pushing his employees hard. His sugar refineries worked 330 days a year, compared to 270 days for his competitors in Europe and America.

His coup in Malaysia made him rich. By 1961, 80% of Malaysia’s 250,000 tons of refined sugar sold per year passed through Kuok’s hands. He says that he made about $3 billion in Malayan dollars from that sugar refinery project alone.

The gambler in the City of London

After getting into the sugar game, Kuok was rich. He started taking active positions in the sugar market speculating via sugar futures. It was a risky game: with the amount of leverage he used, he could make massive gains - but also go bust in an instant.

He started making trips to London, making friends with the top sugar traders in the world. He watched how they operated and asked questions about the mechanics of the market. By 1963 he was trading more than ever - across every single season. Sometimes in London and sometimes from his home in Singapore.

During 1963 alone, he almost quadrupled his entire capital from $5 million Malaysian-Singapore dollars to $19 million.

Robert recounts one story of the summer of 1963 when he went long 20,000 tons of physical sugar. The price collapsed from £40 per ton to £33. By this moment Robert feared he would be wiped out completely.

Another ten to twelve days passed. The price continued to sink to a new low of £30.

Luck would eventually bail him out. In September 1963, Hurricane Flora hit the Caribbean and sugar prices soared from £30 per ton to £60. Kuok ended up making the most money he had made in any short period of his life.

But the story could have turned out very differently and he still wonders what could have happened if the market had turned against him that summer of 1963.

Going into other commodities

By 1964, he was juggling three businesses:

- Sugar refining

- Imports into Malaysia

- Futures trading

But he wanted to do more. One thing he learned from the Japanese is that you should focus on products for which there are large, established markets and for which demand is uniform and sustainable. He eschewed all fads and products subject to frequent changes of taste.

So he went into the flour industry. He started to import flour directly from Australia, bypassing distributors such as Sime Darby and Guthrie. Kuok called up his friend Khir Johari once again to award him a flour mill license and received a scarce license to set up a flour mill. And yet again, he managed to secure a monopoly: Khir Johari made sure that imports of flour would be banned.

Knowing that their import businesses were suddenly in danger, the British hongs were in big trouble. Sime Darby didn’t have any local flour mills and didn’t have any license either so their entire flour business vanished in an instant. Knowing that the Kuok Brothers would take over, Sime Darby sold them key Blue Key brand name to them for a mere pittance - just $25,000. But they had no choice. The Malaysian government had basically given Kuok yet another monopoly.

Making friends in Indonesia

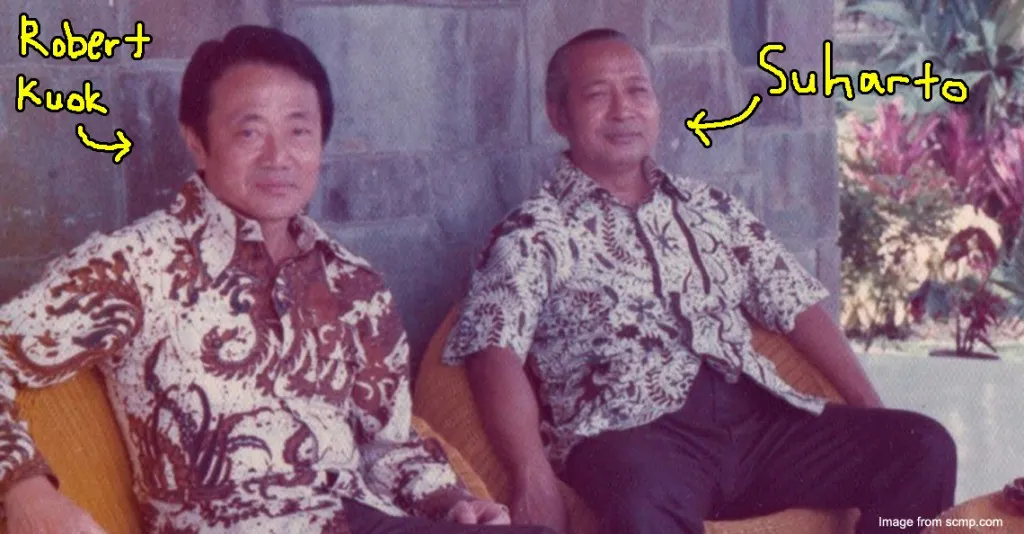

After dictator Suharto came to power in 1966, Kuok moved his focus to Indonesia. A huge market in close proximity to his home base of Singapore.

A new friendship with another overseas Chinese trader called Lim Sioe Long gave him access to Suharto. He suggested to Sioe Long to start flour mills in Indonesia and for them to become partners. Sioe Long relayed the information to the President and Suharto thought it was a good idea.

Since the project was restricted to Indonesian nationals only, Kuok had to use Sioe Long as a custodian for his shares. In other words, during the decades working together with Sioe Long, Kuok didn’t have a single proof that he owned shares in any of his Indonesian flour mills. That just shows the amount of trust that existed among the overseas Chinese traders throughout Southeast Asia. Lim Sioe Long honoured his words and paid out dividends with regularity.

The new partnership first set up a plant milling 150 tons of wheat in 1971. By the time Robert left in 1992, it was milling over 7,000 tons of wheat per day in Jakarta and 5,000 tons in Surabaya.

And Kuok was the company that shipped nearly all of the wheat to Indonesia, taking a cut as a supplier as well. He also set up a Singapore-based shipping company called Pacific Carriers for the purpose of shipping wheat and took a cut on shipping as well.

After a few decades, he started feeling short-changed by Lim Sioe Long’s son Anthony, who later controlled the family’s Salim Group. He diluted Kuok’s shareholding in a series of transactions. So he got out in the 1990s, ending his relationship with the Salim Group.

He also did other deals in Indonesia, including with Yani Haryanto, who lived just across the road from Suharto in Jakarta. Haryanto managed to secure a contract from Suharto to buy rice and sugar for Indonesia. And the Kuok Brothers were responsible to sell the rice and sugar to him from overseas. The volumes were incredible - roughly half a million tons of sugar passed through Robert’s hands, every single year.

Creating an international hotel chain

In the late 1960s, Robert was eager to diversify away from commodity trading because of his experience in London. He saw commodity trading as inherently risky. He wanted stability and looked for the property market to provide it.

In 1968, Kuok was offered 10% shareholding in the land where Shangri-La Singapore sits today. A fantastic plot of land - just a stone’s throw away from the main shopping artery of Orchard Road.

He first wanted to build single-family villas but a friend quickly advised against it. The plot was much better suited for a hotel. So they built the Shangri-La hotel on Orange Grove Road. This is the hotel Donald Trump stayed at during his meeting with Kim Jong-Un in Singapore in 2018 - showing what a success the hotel remains, 50 years on.

Kuok first teamed up with Seattle-based Western International to run the hotel. They took a $200,000 front-end fee for their expertise during construction and then 5% of gross operating profit after the hotel opened for business. But Western made a huge mistake in the contract: saying that the contract would only stretch for ten years.

Robert jumped on the opportunity to break the contract. In 1978, Kuok told them off and set up his own hotel management company instead: Shangri-La Hotels. Today, the Shangri-La Group operate 100 hotels and own 80 hotels across the world.

A second family in Hong Kong

In the 1970s, he started to stray in his marriage. He fell in love with a woman called Pauline and took her with him to Hong Kong in 1979. He felt Hong Kong’s taxes were more favourable and he also felt it was closer to the action with Communist China developing into a more prosperous country.

Just like his father, he decided to have a second family. He bought a townhouse in an area called Strawberry Hill at Victoria’s Peak and seemed to enjoy family time, perhaps for the first time in his life.

In Hong Kong, Kuok noticed that office rents kept on increasing. He felt that he might as well hedge himself by owning the building itself. That was the start of Kuok’s property business, which has now become a separately listed entity called Kerry Properties.

He went deep into property investments in mainland China, encountered corruption and unreliable business partners. But thanks to the underlying growth in the economy, he did well for himself. Kuok’s property portfolio in China is now worth billions.

He even bought South China Morning Post in 1993. And his trading business merged with that of a relative to form Wilmar International.

Today, 94-year old Robert Kuok is Malaysia’s richest man, with an estimated fortune of US$12.6 billion. While the pandemic hurt some of his hospitality-related businesses, he remains one of the most powerful businessmen in Asia.

Words of wisdom

When in trouble, seek others’ advice:

“When in doubt about a project, chat with a man cleverer than myself and offer him a joint-venture deal.”

Keep the end customer happy

“Never be the cause of high prices of staple foods, because food staples are the food of the poor.”

Motivate employees through ownership of equity

“Maintain reservoirs of shares in each holding company that were not owned by anyone… My co-workers of the 1960s may no longer be the achievers of the 1970s… So, we always kept blocks in reserve to reward the new and future achievers.”

Get real-life experience

“I don’t believe a man can become a successful businessman merely by reading books. I think it’s better to observe the falling leaves than to read someone else’s advice.”

What qualities to look for in new hires:

“The important thing is unity in the group: Teamwork, hard work and zero treachery.”

Pick yourself up from failures:

“Failure is the mother of success… if a person fails but has enough strength of character, he’ll bounce back with even greater vigour.”

What’s still lacking in the People’s Republic of China:

“The two greatest challenges facing China are the restoration of education in morals and the establishment of the rule of law.”

On diet:

“My favourite protein is fish… vegetables and fruits are also the best foods that one can have.”

Be humble to gain support:

“If a person is truly humble, most people will do anything for him; but if he is a hocky person, out of 20 “friends,” barely two will help him.”

An outsider’s perspective on Robert Kuok

I felt Robert Kuok’s biography was somewhat self-serving. So to get an outsider’s perspective on him, I went through Joe Studwell’s book Asian Godfathers, which portrays Robert Kuok in a somewhat different light.

Rent-seeking is what made Robert Kuok rich:

“Robert Kuok modernised the rentier system in south-east Asia.”

“Kuok remains the controlling shareholder in three of Malaysia’s four sugar refineries and is allocated the bulk of a government-set quota for the import of raw sugar. The arrangement is justified on the grounds that Kuok has kept sugar and flour prices stable in the face of international market fluctuation.”

Contacts in the government helped him secure those deals:

“When other businessmen tried to challenge Kuok’s near-monopoly in Malaysian sugar under the new regime, the government rebuffed calls for reform.”

“Robert Kuok’s big early real estate deals, for instance, were not based on transactions with the British, but with the Johore royal family.”

“Kuok encouraged Liem to also lobby Suharto for an import monopoly on wheat, for flour milling, to be shared with the military. Kuok and Liem became co-investors in wheat and sugar trading businesses, and sugar cultivation, for three decades.”

He works his employees incredibly hard:

“Board members at the South China Morning Post, controlled by Robert Kuok, were not sure where to look at an infamous February 2003 board meeting when the patriarch lost his temper with son Ean, then aged 48, bawling him out in front of a room full of directors.”

“Robert Kuok’s chief slave Richard Liu, who was on occasion reduced to tears by the stress of his work, dropped dead at Kuala Lumpur International Airport on Chinese New Year’s day 2002.”

His businesses have not worked in the best interests of minority shareholders:

“Robert Kuok, whose listed businesses have a long track record of underper-forming the broad indices of the markets in which they are traded, is a master.

“For many years he had a Singapore-listed dry bulk shipping company called Pacific Carriers Ltd (PCL), whose price and dividend performance were so appalling that the counter became known to traders as Please Cut Losses. In 2001 Kuok took PCL private at a hefty discount to its net asset value (NAV – or the book value of the company’s assets). Hardly had the wounds of minority investors in the Singapore market healed when the tycoon announced, in October 2003, that he was launching an IPO of a PCL subsidiary, Malaysian Bulk Carriers (MBC), up the road on the Kuala Lumpur exchange. Kuok had already sold 30 per cent of MBC to the Malaysian government at a healthy price and his local investment bank, run by the deputy premier’s brother, ensured the IPO was an aggressively valued success.”

“Kuok then sought to relieve long-suffering investors in his Hong Kong property arm, Kerry Properties, with an April 2003 privatisation offer at a discount of 53 per cent to net asset value. He bawled out his chief financial officer when minority investors failed to bite.”

Some personal reflections

Studying Robert Kuok’s life, it’s clear why he became rich.

He was more greedy and more hard-working than almost anybody else. He hardly saw the children in his first family grow up.

Without Kuok’s exclusive distribution contracts, tariff protection and licenses in Malaysia, he would not have made it big in sugar and flour. He made billions on sugar alone. The same story played out in Indonesia thanks to his strong relationships with Lim Sioe Long, Yani Haryanto and Suharto.

Throughout his life, Kuok has been known to collect money via side deals. He engaged through side deals during his time as an assistant working for Mitsubishi during the war. In joint venture deals, he would be a supplier and distributor as well. There are rumours that Kuok does the same in his listed Shangri-La businesses as well, though I haven’t been able to confirm this definitively.

So what can we learn about his life story? I want to emphasise the following:

- The incredible work ethic of many overseas Chinese such as the Kuoks, who completely dominate trade and business across Southeast Asia. It may have partly to do with the trust needed to operate in these treacherous markets where the rule of law is weak. Dealing with people within your own ethnic group helps bridge the trust gap. But it is also clear that the overseas Chinese have worked harder than almost any other group in the region.

- Southeast Asian countries are to a large extent rent-seeking economies. Many of Robert Kuok’s deals were mispriced government concessions that enabled him to line his own pockets at the expense of taxpayers and consumers. Such concessions are a relic from the colonial era when contracts and bank loans were handed out to favoured parties in the European elite. And these types of concessions live on until this day.

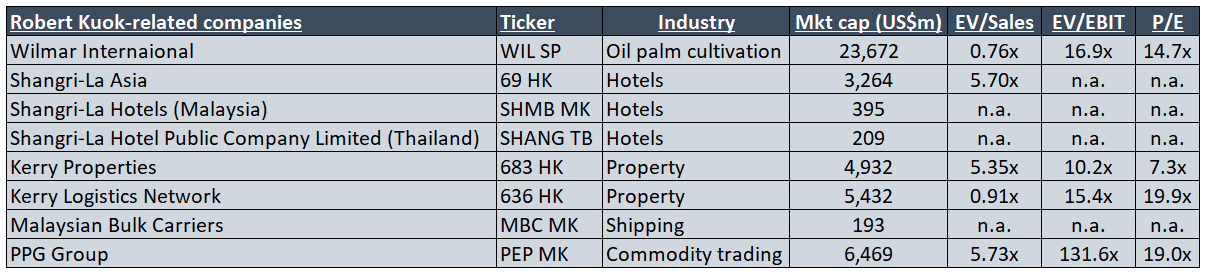

Stocks controlled by the Kuok family:

The long-term performance of these stocks has been lacklustre. Given what I now know about Robert Kuok, I suspect it has something to do with corporate governance within the group.