Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may from time to time have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is disclosure and not a recommendation to buy or sell.

Have a look at the below chart. It shows the relative GDP per capita for emerging markets compared to their developed market counterparts in 1960 (x-axis) vs 2016 (y-axis).

What stands out in the above chart is that most of the countries and regions that grew wealthy over the past 50-60 years are actually in East Asia. These countries include:

Korea

Taiwan

Singapore

Hong Kong

China

What do they have in common? Economists usually point towards two factors:

A Confucian work ethic

The East Asian development model

The first factor is difficult to analyse and highly qualitative in nature. But the second factor is worth exploring - exactly how these countries developed and what it implies for stock selection.

Exports drive growth in emerging markets

Worth noting is that exports are the main driver of growth in emerging markets. Emerging markets don’t become more productive by innovations, but rather by selling foreigners a higher volume of goods.

In other words, a country that is not growing its exports should not be considered an “emerging market” in the true sense of the word.

There are two types of exports: commodity exports (typically natural resources) and manufacturing exports.

Commodity exports

Commodity exports from emerging markets tend to be stable volume-wise whereas prices are volatile. That makes the economic growth of commodity-producing countries volatile as well. You’ll want to play the cycle.

A few countries have actually managed to become rich from natural resources (including Qatar, United Arab Emirates) or tourism (Maldives). But their population are typically small (below 1 million), enabling their per capita income to reach high levels. And wealth in such economies tends to be concentrated around a narrow elite. Most countries do not become rich by simply selling commodities to the wealthy part of the world.

Network effects in light manufacturing

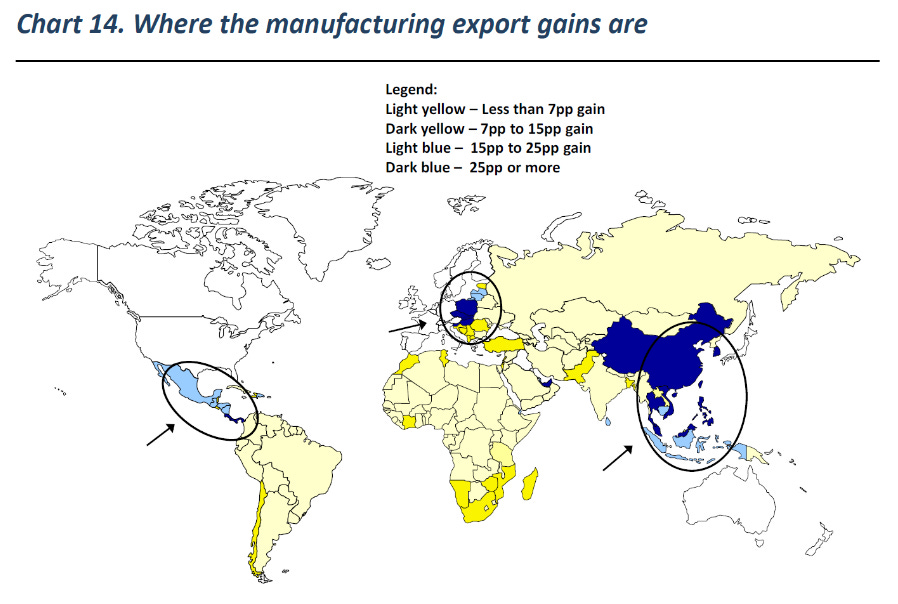

The countries that have developed manufacturing capabilities over the past few decades are, as mentioned earlier, East Asian countries, but also to a lesser extent formerly Communist countries bordering Western Europe:

There seems to be a network effect in manufacturing. Countries in East Asia and Eastern Europe are either close to key trade routes between Japan / Korea and Western markets. Or they share borders with them. Proximity reduces transport cost. And supply chains become more efficient if say all components of an iPhone come from neighbouring countries.

Light manufacturing exports

So the common denominator across all East Asian countries is that they became rich by building out a manufacturing sector. The industrial policy followed by these countries is similar to the one recommended by German-American economist Friedrich List, leading to the following development trajectory:

Farmland redistribution: In the early stages of development, the majority of the population is employed in agriculture. Farmland redistribution improves productivity. That, in turn, leads to higher export revenues and the foreign exchange needed to buy machinery and other capital goods.

Improved farm productivity: Improved farm productivity also frees up the labour force for factory jobs, including in the manufacture of export goods.

Government protection: Protection can help domestic manufacturing industries until they are strong enough to compete in the global market. The tradeable nature of manufactured goods means that in the absence of such protection, local companies will be subject to tough global competition.

Government subsidies: Specific policies such as cash subsidies, cheap land and access to bank loans can accelerate the process of building a local manufacturing base. The government should be careful not to pick winners, however. If anything, they should just weed out the weaker companies and let them fail.

An emerging middle class: Once factories are set up to manufacture export goods, individuals move from farms to cities to enjoy higher salaries. They move into a middle class and their consumption patterns change. Certain goods such as autos, commodity housing, home appliances, consumer electronics are purchased for the first time. Service professions such as software outsourcing or call centres, on the other hand, are typically not big enough to create a middle class.

Government revenue improves: Higher exports help improve the fiscal balance and the trade balance, stabilising the currency and the government budget. The government uses new fiscal revenues to build infrastructure, helping improve delivery speeds and overall supply chain efficiency.

Technological spill-over effects: By introducing foreign companies to manufacture goods in the country, they bring in technological know-how. Eventually, employees in those original factories set up competing factories across the road producing similar goods but at lower prices.

Domestic brand names emerge: In the next stage of the process, those competing factories create their own brand names, which they use to sell goods into developed markets. At this stage of the process, Friedrich List recommends the developing country advocate free trade for the first time since it will finally be able to compete.

Democracy doesn’t necessarily help

So a key question is how a government is able to support and nurture a manufacturing sector. To achieve the reforms necessary, certain conditions are needed. Vested interests tend to be against the redistribution of land that could raise productivity. Vested interests also tend to control resource allocation through ownership of a country’s major banks.

A strong government is therefore needed to push through reform in the face of strong opposition from vested interests.

This is exactly what can be observed in the data. The growth rates of countries that are authoritarian have historically been higher than those of democratic countries. Key explanatory factors seem to be a better ability to fight vested interests and undertake (sometimes painful) reforms.

Another problem with democracy in emerging markets is that illiterate individuals are easily influenced by those already in power. Vote-buying is rampant in India and Indonesia, for example. In such countries, television and film stars are more likely to get in power than serious reformers.

A particular problem with democracy arises when the demographics of a country comprises a successful minority and an impoverished majority. Politics in Malaysia, for example, tend to have racial undertones. Equal rights for all ethnic groups is therefore undermined by the political system.

So in the early stages of development, rule of law is more important than democracy per see. Either way, a strong government is needed to fight vested interests.

Of course, a risk with an authoritarian rule is that a madman eventually comes to power, undermining the system from the top-down. Reforms could easily be backtracked, returning the country into some form of kleptocracy.

The current outlook

China followed the East Asian development model to perfection, learning from other East Asian peers before them: Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. In terms of income per capita relative to developed markets, China is at a similar spot to where Korea and Taiwan were in the 1990s. It just remains to be seen whether the country can continue to move up value chains or whether it will remain return to the inward-looking policies of China in the 1950-1970s.

The Asian country with the brightest prospects for export growth is Vietnam, in my view. The country is in the middle of a shift from agriculture to manufacturing exports. There will be opportunities in a variety of consumer sectors in the next decade or two as Vietnam grows richer, including commodity housing, household appliances, autos, etc.

Despite all this, GDP growth is not a major deal

So we know that some countries in East Asia have managed to become rich. Is that a reason to allocate more of your portfolio into future possible success cases?

The data is not clear on that point. Despite the proof that the East Asian development model works in raising GDP / capita, there is no proof that economic growth matters for USD stock returns. Many of the best EM performers over the past two decades have been commodity exporters such as Russia, Chile, Colombia, Peru and Indonesia.

Why? Because there are other factors that matter even more than income growth, for example the starting valuation multiple, the currency exchange rate, index composition, share dilution from highly-priced IPOs, returns on capital, corporate pricing power, corporate governance, etc.

Conclusion

I think there are a few separate bets you can make in emerging markets. Don’t trick yourself into thinking that GDP growth is the end-all-be-all.

The cyclical bet: Emerging markets are cyclical, so bet on the cycle. Perhaps because you’re bullish about a particular commodity because a country is recovering from a capital outflow-driven bust with a current account finally turning positive. Or because you think tourism is about to recover after a pandemic.

The middle-class consumption bet: The other bet you can make is what I discussed in this essay: betting on poor countries becoming rich. Just be aware that very few countries manage to make the journey from poor to rich. And don’t buy stocks indiscriminately: focus on stocks that benefit from a rising currency (driven up by ever-increasing exports), from higher middle-class consumption and lower interest rates.

The innovation bet: Bet on specific innovative companies that do something new and different. Such companies also exist in emerging markets, but perhaps more so in those that have already crossed the “middle-income trap” and are on their way to become rich countries.

Either way, don’t trust the “emerging market” narrative that all poor countries will automatically make the journey to a developed market. Only a few select countries will manage to make such a transition.

And even if you can predict which country will become rich, don’t expect to outperform those investors speculating in say Peruvian or Russian stocks. What company you invest in - and at what price - often matters more than the broader macro story.

If you would like to support me and get 20x high-quality deep-dives per year, thematic reports and other reports, try out the Asian Century Stocks subscription service - for the price of a few weekly cappuccinos.