Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

- The expression “platinum group metals” or “PGMs” refers to the six metals: platinum, palladium, rhodium, ruthenium, iridium and osmium. The reason they’re often grouped together is because they have similar characteristics in that theyr’e durable and resistant to corrosion.

- While there’s some industrial and jewelry-related demand for platinum, the demand for PGMs primarily comes from catalytic converters used in gasoline vehicles. Some worry that we’re transitioning to electric vehicles and that the demand for PGMs will, therefore, be in secular decline.

- But I want to add some nuance to the discussion, pointing out that the demand for electric vehicles remains relatively muted outside of China. Instead, hybrids, including plug-in hybrids, seem to offer the best of both worlds in terms of low prices and convenience.

- If hybrids end up winning, that matters a great deal for the demand for PGMs, because they contain 10% more metal than conventional gasoline vehicles. In addition, tighter emission standards in India and elsewhere also increase the demand for catalytic converters.

- Meanwhile, the supply of PGMs continues to tighten, especially for platinum. Production is going down, and no major projects are on the horizon. Further, the lead time for new projects is about 8-10 years. That sets the market up for higher prices over time, especially if Russia restricts supply or the US Dollar weakens.

- Towards the end of the post, I discuss ways one can get exposure to the platinum group metals, including miners and funds.

American Express calls its premium credit card “The Platinum Card”, in reference to how scarce and valuable it is.

And platinum is indeed a scarce metal. If you take all platinum mined throughout history until today, it would only fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool up to your ankles. The same is true for platinum’s sister metals palladium, rhodium, ruthenium, osmium, iridium which are frequently referred to as Platinum Group Metals (PGMs).

In the June 2024 issue of the Boom, Gloom & Doom Report, Marc Faber wrote about platinum and related metals. He argued that the market is heading for a substantial supply shortfall while prices are touching all-time lows.

I wanted to dig into his arguments, and see where he’s coming from. So in this post, I’ll discuss what the platinum group metals are and the key drivers of the market.

Table of contents

1. The demand for platinum group metals

2. The supply picture

3. Intersection between supply & demand

4. The investable universe of PGM assets

5. Conclusion1. The demand for platinum group metals

Platinum is one of the rarest metals on earth - roughly 30x more rare than gold on the earth’s crust.

But the demand for platinum in jewelry lags behind that of gold and silver. It doesn’t have the same sheen and patina tends to form over time. It’s also more easily faked and difficult to distinguish from say tungsten.

What makes platinum special is its durability and resistance to corrosion. It can be hammered or pressed into a shape without cracking or breaking. For example, one gram of platinum can apparently be stretched into a thin wire that’s over a mile long without losing its toughness.

In addition, the high melting point of 1,768 degrees Celsius means that it can withstand harsh environments without any degradation. That makes it perfect for industrial applications, in particular for catalytic converters in the automotive industry.

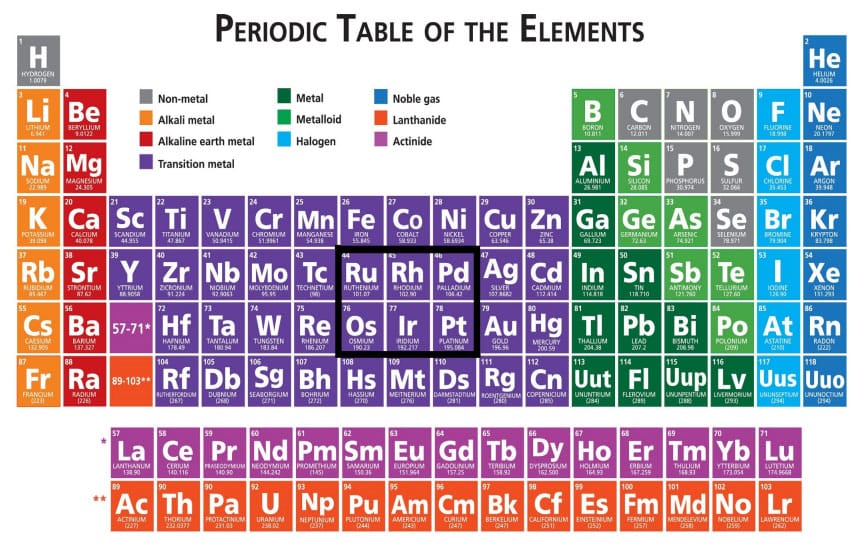

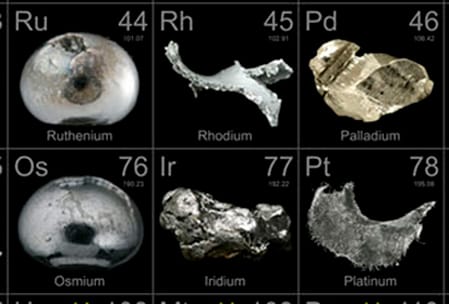

So what are the Platinum Group Metals (“PGMs”)? In the periodic table, platinum is often grouped together with palladium, rhodium, ruthenium, iridium and osmium.

The common denominator between these six metals is that they all have a high melting point, extreme mechanical strength and stable electrical properties. They’re frequently interchangeable in industrial applications. And in nature, they’re almost always found in some combination of each other.

In reality, only three of the PGMs are finding much practical use, namely platinum, palladium and rhodium. These three and sometimes referred to as the “3E”, where the letter E stands for “elements”.

The use of platinum took off after Spanish explorer Antonio de Ulloa’s 1735 expedition to Quito, Ecuador. He spent ten years in South America, keeping a diary of what he observed on the trip, including witnessing the use of a variety of metals. In particular, he described a new metal which he called “Platina”:

“In the district of Choco are many mines of lavadero or wash gold. Several of the mines have been abandoned on account of the Platina, a substance of such resistance that when on anvil of steel, it is not easy to be separated. Nor is calcinable, so that the metal enclosed within this obdurate body could only be extracted with infinite labor and charge.”

Platinum later became named “The white gold”, “The Little Silver” or the “Seventh metal”, as it was only the seventh known metal at the time.

Initially, scientists didn’t know what to do with the metal. Someone suggested using platinum for telescope mirrors, because it resists the vapors of the air. But the heft of the metal made it unsuitable for this particular use.

So it was only through the discovery of x-rays in 1895 that platinum started to be used in industrial applications thanks to its excellent heat resistance.

Platinum’s sister metal palladium was discovered and classified by Englishman William Hyde Wollaston after importing crude platinum ore imported from South America in 1802. He found a way to extract the palladium from the ore, though keeping the discovery to himself for years to make money out of it. Eventually, the truth got out, however. He also discovered rhodium just a few years later. This time around, he published his findings in a publication that announced the discovery to the world.

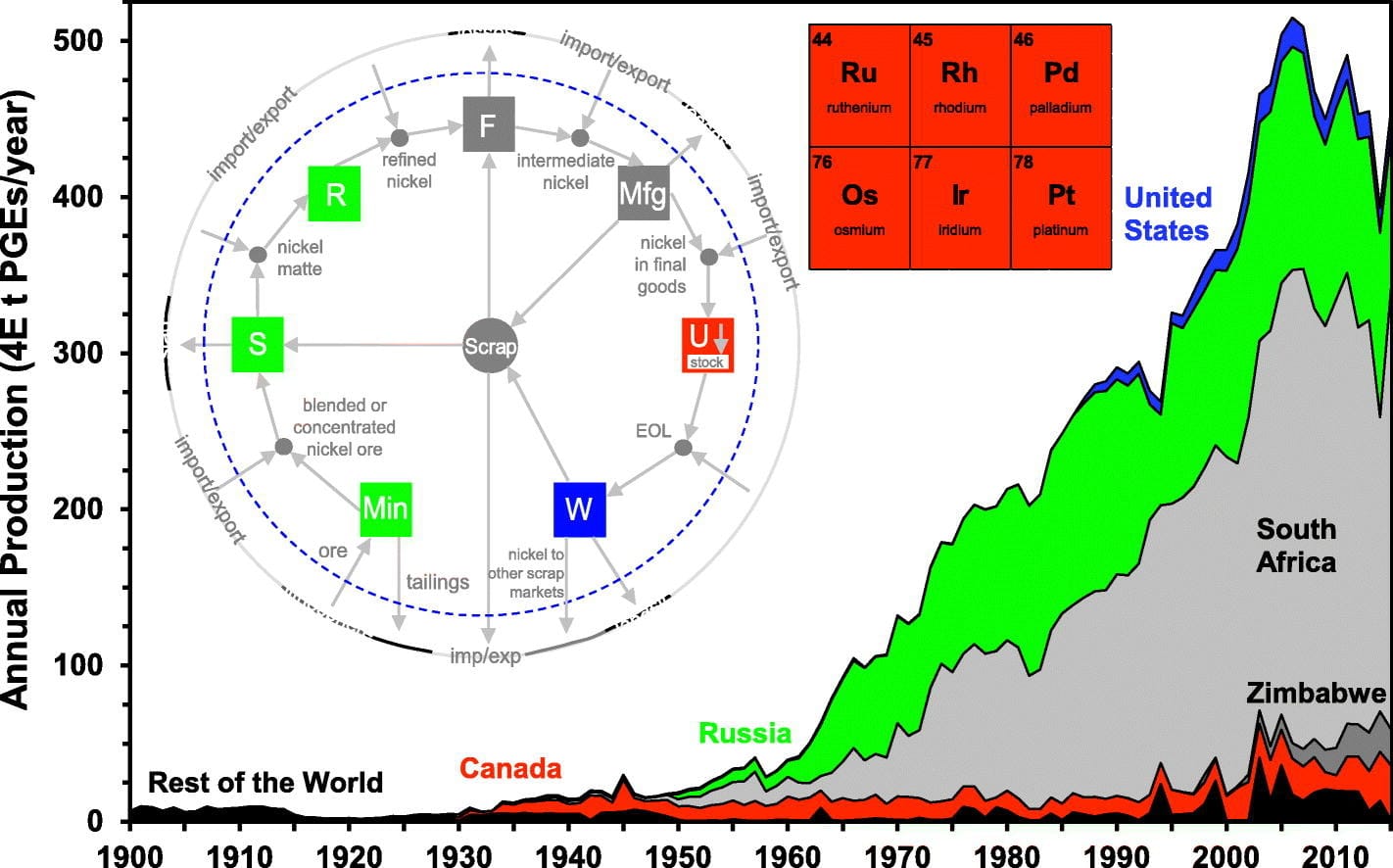

The mining of PGMs was modest until the 1950s. But then came the invention of “catalytic converters”. These would turn nitrogen oxide and other exhaust fumes into water, carbon dioxide and nitrogen, significantly reducing the smog created by automobiles. A key ingredient in making these “catalytic converters” was platinum, helping speed up the reaction without degrading in the process.

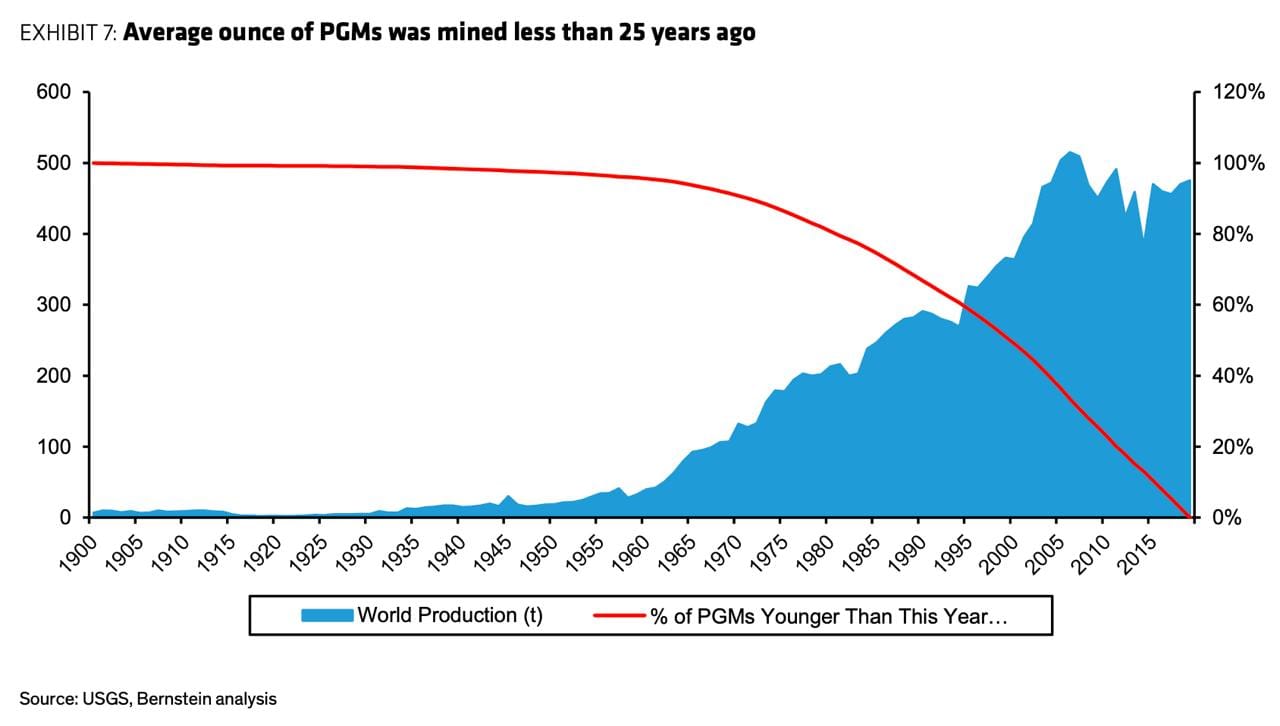

The catalytic converter was the “killer app” that caused demand for the PGMs to skyrocket. Since the 1950s, production has gone up in pretty much a straight line:

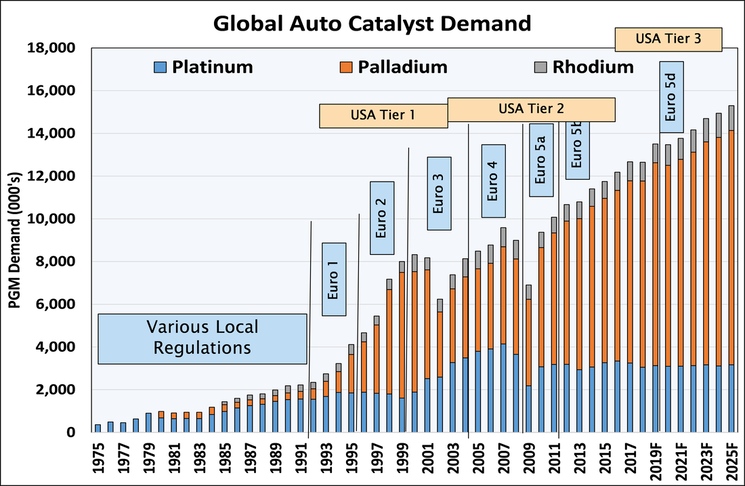

The US Clean Air Act in 1970 also it pushed automakers to install catalytic converters into their vehicles. And by 1975, all US cars were required to have catalytic converters. Soon, they became mandatory in other countries, too.

The next shift came in the 1980s when three-way catalytic converters were invented. Instead of platinum, these would contain a mixture of platinum, palladium and rhodium. This shift caused the demand for palladium to skyrocket. In fact, palladium is even more effective than platinum when it comes to reducing tailpipe emissions.

Since the late 1990s, diesel engines have become popular in light-duty vehicles as they’re more fuel-efficient. Since diesel engines require more platinum than palladium, demand for platinum rose a bit. And then diesel engines fell out of favor yet again over the past ten years.

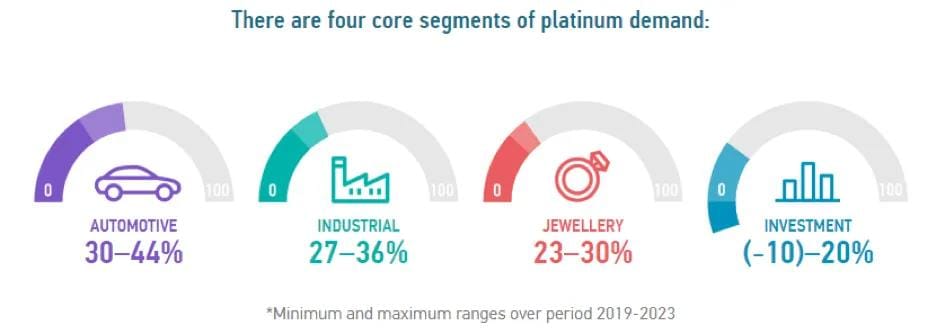

So why do I call the platinum group metals “anti-EV commodities”? Because catalytic converters account for 83% of all demand for palladium, 90% for rhodium and 40% for platinum. It is the major factor driving the demand for the PGMs as a whole.

Now, electric vehicles do not contain any catalytic converters because hydrocarbons are not used as fuel in the first place. That’s made investors nervous about the metal, assuming that an “electric vehicle transition” would bring the end to the use of PGMs.

But I think that view is misguided. While electric vehicles are fine to drive, it is not obvious at all that they’re going to be cheaper than conventional gasoline vehicles anytime in the foreseeable future.

The biggest difference in cost between gasoline vehicles and electric vehicles is procuring an engine vs a battery. An internal combustion engine costs around US$2,000, whereas a battery costs around US$7,000. And the battery degrades roughly twice as fast as an engine. So you end up with an initial cost that’s perhaps US$10,000 higher. That could change, but a significant portion of the cost is from raw materials, which are unlikely to get much cheaper.

While electricity is cheaper than gasoline, we also have to consider the range issue, flammability and long charging times.

Electric vehicles haven’t shown the typical S-curve demonstrated by new inventions like the smartphone. A McKinsey study showed that 40% of US electric vehicle buyers want to return to internal combustion engine cars. Electric vehicles also sit much longer on US dealer lots. My conclusion is that there simply isn’t much demand for them.

I think government subsidies and mandates are required the success of electric vehicles. From what I can tell, only in China is the government forceful enough to bridge the still-wide gap in the value proposition of an internal combustion engine vehicle and an electric vehicle. Perhaps the calculus will change with the commercialization of solid state batteries, but that is by no means a certainty.

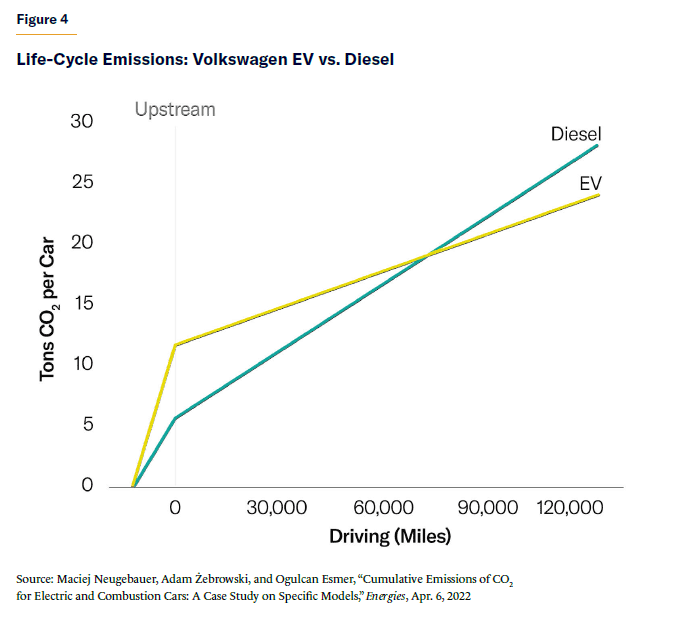

I don’t think the CO2 calculus is straightforward, either. Lifetime CO2 emissions require electric vehicle miles driven to exceed a certain level before bcoming favorable for electric vehicles. If we really want to reduce CO2 emissions, we should push for public transport subway systems and reform zoning laws to create denser cities, not subdisize the purchase of electric vehicles.

But the data is clear on one point: hybrids are actually popular among consumers. Google search queries for hybrids remain higher than for battery electric vehicles. Hybrids seem to offer the best of both worlds: a better CO2 lifetime emissions profile, lower gasoline consumption and the cost is only about US$2,000 more than a conventional vehicle.

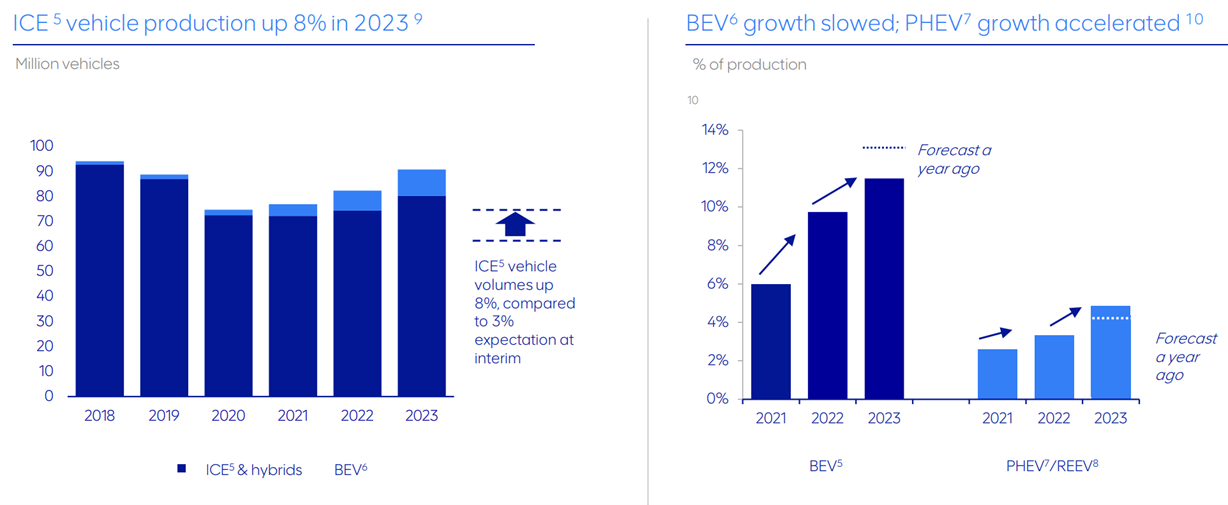

Globally, the share of hybrids doubled in 2023 from 3% to 6%. Meanwhile, the growth in the sales of battery electric vehicles seems to be decelerating, going from 12% to 13% in the past year. The deceleration in growth has been most evident outside of China. But even in China, hybrids seem to be taking over, with plug-in hybrids now representing 30% of new energy vehicle sales.

What impact will hybrids have on the demand for PGMs? It will be positive, as they contain 10% more metals due to needing more frequent cold starts and shifts between engines.

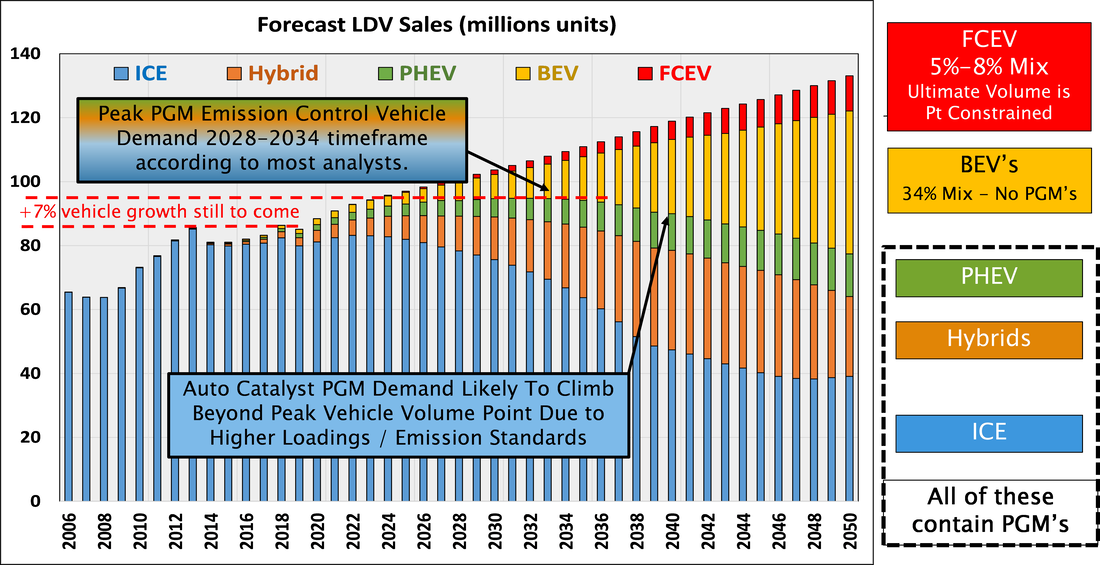

Assuming a global electric vehicle sales mix of 34% by 2050, you’d see a pattern of flat gasoline / hybrid vehicle volumes until the 2030s. And given the higher demand for PGMs in hybrids, there will be actual growth in the demand for PGMs.

The big wild card is fuel cell vehicles, which use hydrogen as fuel instead of gasoline. So-called fuel cells take the hydrogen from the tank and combine it with oxygen from the air, producing H20 - water. If we were to adopt fuel cell vehicles today, carbon emissions would drop significantly.

The hydrogen itself needs to be produced. Today, most of is made through fossil fuels, e.g. natural gas. But you can also produce hydrogen through electrolysis: putting electricity through water.

In any case, platinum is needed for both electrolysis and the fuel cells within each vehicle. So, a shift to fuel cell vehicles, even if just on the margin, would increase the demand for platinum significantly.

Unfortunately, it seems like a pipe dream. Fuel-cell electric vehicles are more expensive. The hydrogen is costly as it requires compression to liquid form. Hydrogen is also explosive, which is why air-ships never took off in the wake of the Hindenburg disaster.

At the end of the day, gasoline is incredibly energy-dense, easy to transport, and abundant. That’s why I think gasoline is here to stay, at least for now. And that means that the demand for PGMs is likely to stay flat or slightly increase.

In the short-term, the picture is mixed. Gasoline vehicle production is likely to recover to 2019 levels as the automotive chip shortage was weighed down sales during COVID-19. And now, high interest rates are preventing consumers from buying vehicles.

Still, the following chart from Anglo American shows that the sum of gasoline vehicles and hybrids sold rose by +8% in 2023 and is likely to rise further. Meanwhile, sales of hybrids are beating expectations.

Another driver of demand for PGMs will be tighter emission standards. China introduced its China 6 standard in 2021. India also introduced tougher emission standards in 2020 in line with Euro 6 norms, pushing the demand for catalytic converters higher.

So, we know that the demand for palladium and rhodium is likely to stay flat or slightly higher in the next ten years thanks to tighter emission standards and the increased popularity of hybrids, including plug-in hybrids. But platinum is special among the PGMs, because 60% of its demand comes from non-catalytic converter sources.

If you look at correlation charts, you’ll find that the demand for platinum jewelry is highly correlated to that of gold. The demand tends to go up during periods of inflation. It can almost seen as a gold proxy for that reason.

While a significant portion of the demand for platinum in industrial applications comes from recycling, it’s also the case that demand for platinum moves with the cycle. Unlike gold, platinum is also sensitive to economic growth and consumer confidence. And that’s why the demand for platinum might go down a bit if we truly are entering into a global recession.

2. The supply picture

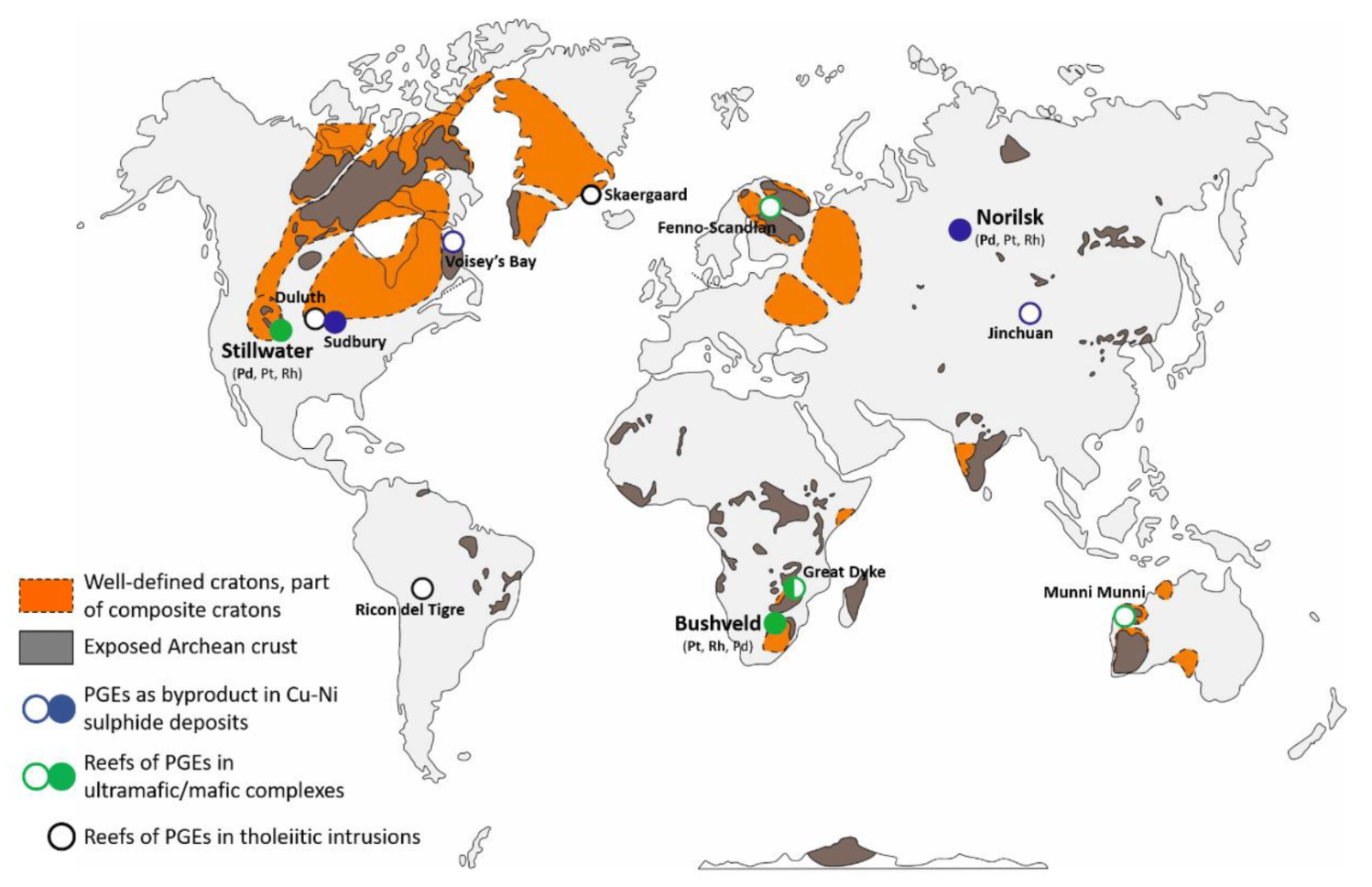

Almost 90% of platinum group metals come from South Africa, Zimbabwe and Russia. In South Africa, you have the Bushveld complex with deposits that are over 2 billion years old. Then you have the Great Dike in Zimbabwe. Finally, you have the Norilsk PGM deposits in Siberia, whose palladium is mined as a by-product of nickel. While there are also promising deposits in Canada and Australia, production from these remains small.

Historically, most of the increase in PGM production has come from South Africa and Russia, with Canada and Zimbabwe playing a much smaller role.

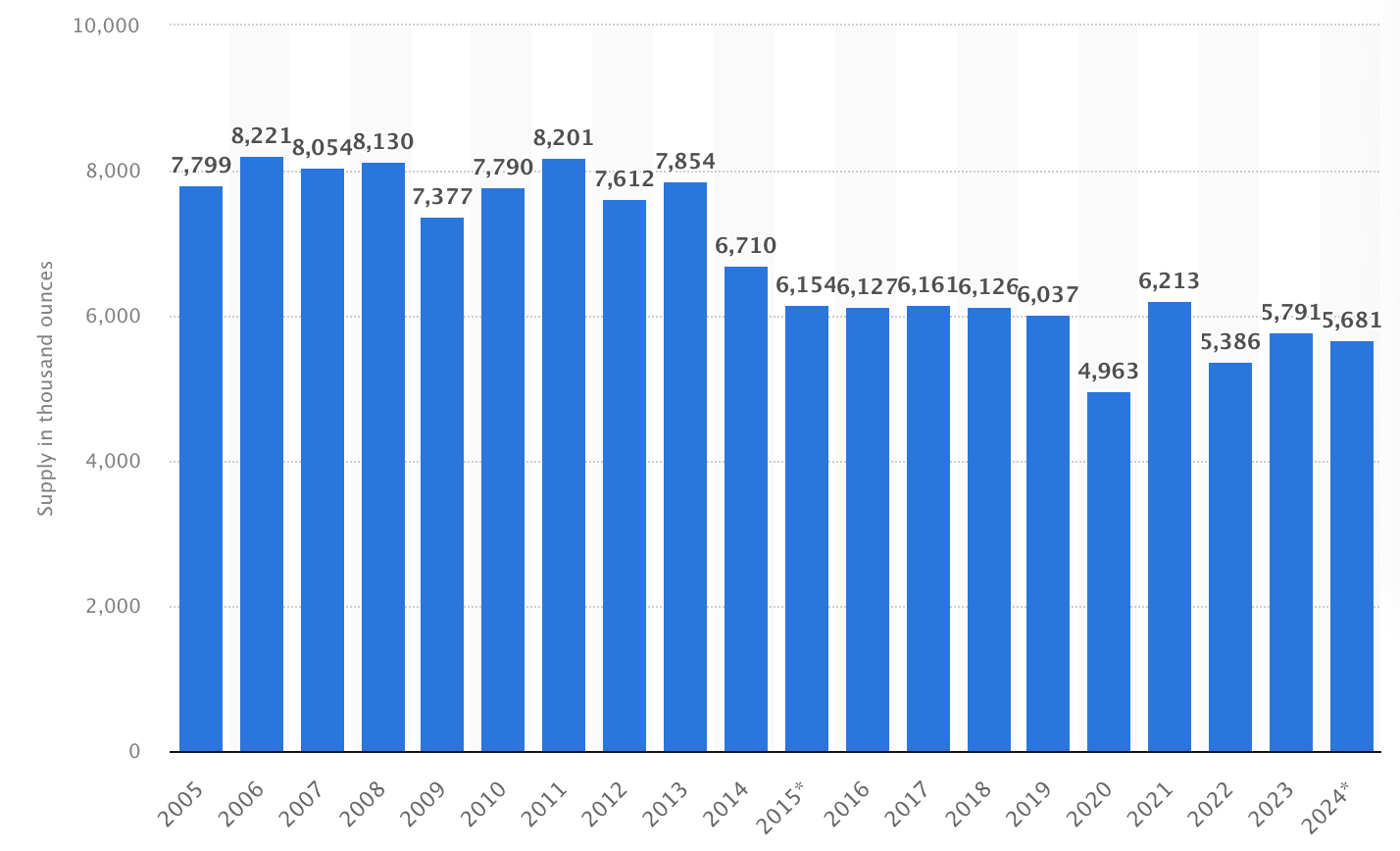

As you can tell, production has gone up over time. But in the past ten years, world platinum production has been declining from around 8 million ounces in 2011 to less than 6 million ounces in 2024. From my understanding, the cuts have mostly taken place in South Africa. You might want to adjust for recycled platinum as well, but even this number has dropped due to lengthening replacement cycles for autos.

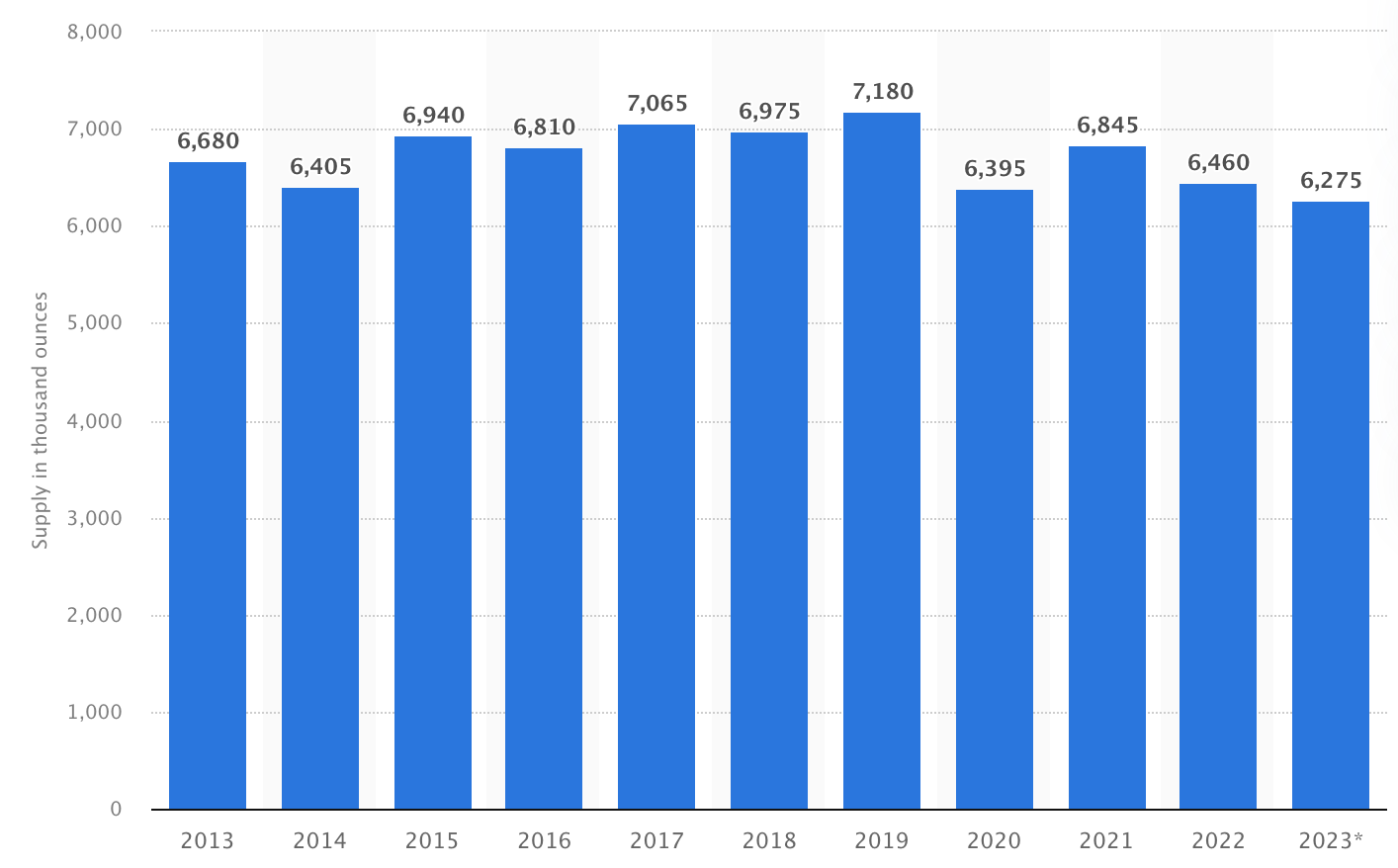

The decline in production is also seen for Palladium, whose supply has been flat to down in the past decade to about 6 million ounces.

And production is likely to shrink further. The World Platinum Investment Council estimates that 25% of all PGM miners are making losses right now. Major producers Anglo American Platinum plans to lay off 17% of the workforce. Sibanye Stillwater announced it’s going to cut 2,600 jobs in South Africa. And Impala is reducing workforce at its mine in Canada.

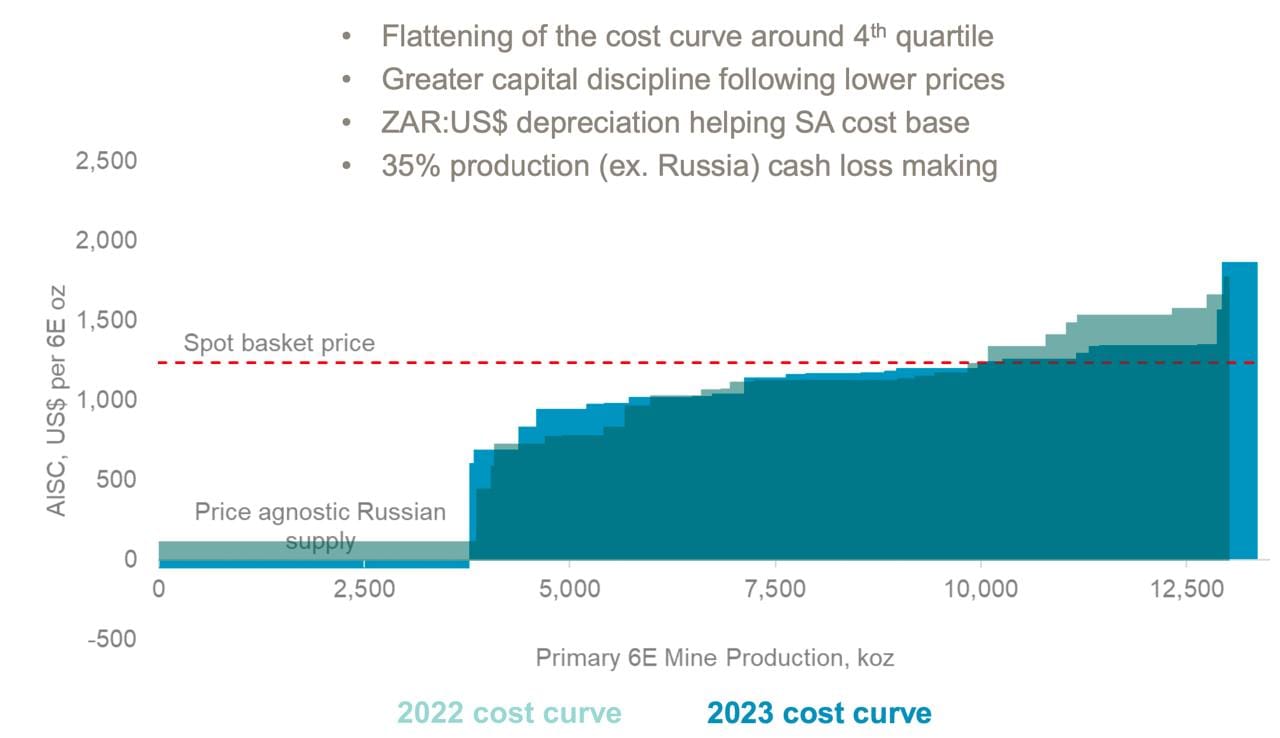

Why? Because prices are too low to make mining worthwhile.

The cost curve for platinum group metals suggests that prices above US$1,500 per ounce are around the 12 million mark. From my understanding, the total production number includes all 6E PGMs. That compares to a platinum price of US$944/ounce currently and a palladium price of US$851/ounce.

But we also need to consider the fact that Russia, South Africa and Zimbabwe are not exactly the most stable countries on earth. If either of them are cut off from global supply, for example Russia, in the case of a global hot war, then the upside to PGM prices could be significant.

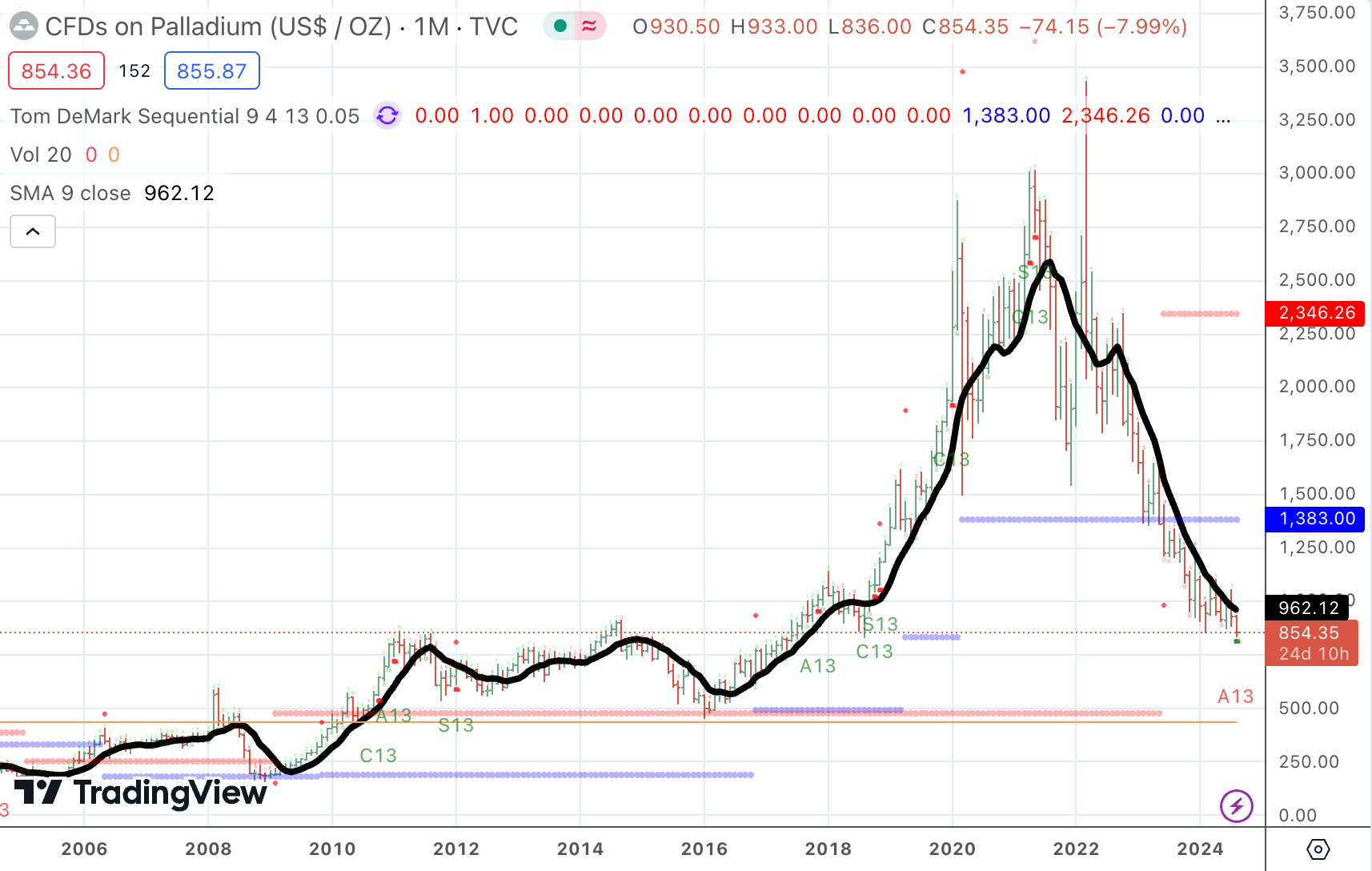

We already saw that potential impact on palladium prices from Russian supply disruptions after the war in Ukraine, when palladium prices went up 5x before falling back to earth.

Further, Norilsk Nickel recently stated that it’s facing difficulties in obtaining the required equipment to continue production. It expects PGM production to reach a 5-year low in 2024. It doesn’t help that nickel prices have dropped recently.

During COVID-19, worldwide mining inflation shot up by +25% per year momentarily. However, the PGM cost curve benefitted from the weak South African Rand, which has dropped roughly 50% vs the US Dollar in the past decade. The real effective exchange rate hasn’t dropped as much but remains low. If the US Dollar starts a weakening cycle, which is my base case, then the cost curve will have to shift upwards, causing PGM prices to rise.

Looking forward, there’s nothing on the horizon that would suggest a change in the overall supply picture. It takes 8-10 years for a new project to come online and there is no meaningful pipeline in place.

The next major projects coming into production include Generation Mining’s Waterberg in 2024 and Marathon in 2025 as well as Ivanhoe’s Platreef in 2025. They don’t seem to change the overall supply picture all that much.

3. Intersection between supply & demand

So there’s no doubt that PGMs are out of favor. Marcelo Lopez of L2 Capital in Brazil recently reported going to the Shanghai Platinum Week where only three out of 500 participants were investors. Nobody’s interested.

He says the event reminded him of going to the Nuclear Association Symposium in 2019, which also only had three investors participating. Since then, uranium prices have quadrupled.

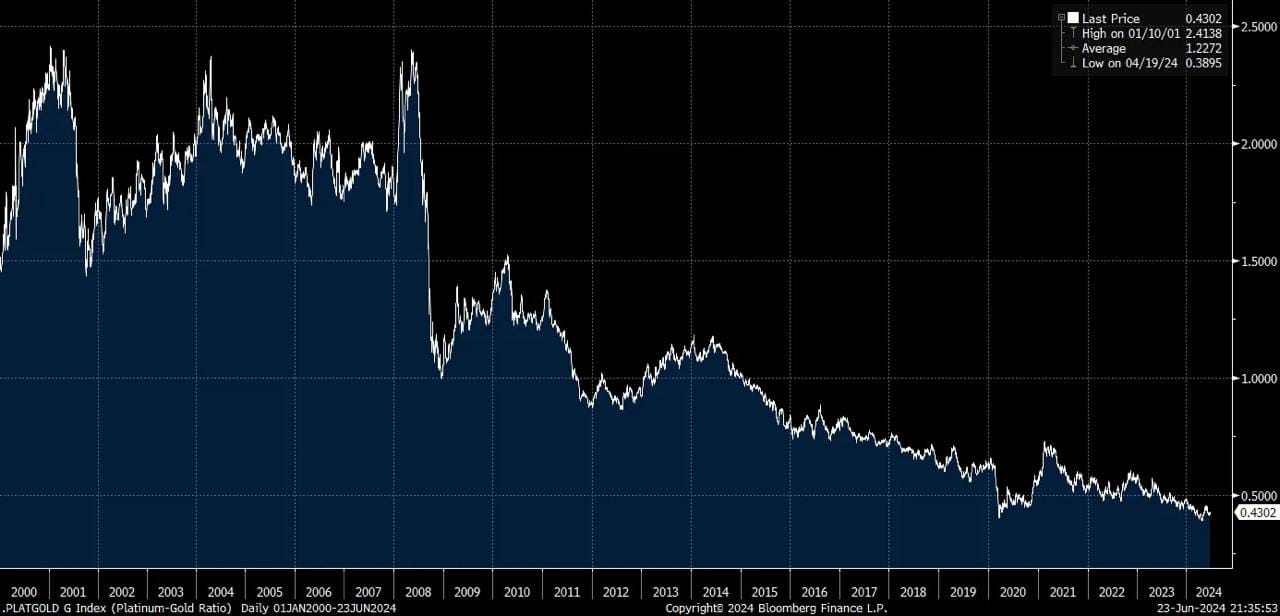

Since 1900, due to its scarcity, platinum has on average traded at almost twice the price of gold. But today, that number has shifted to an almost 60% discount to gold per ounce.

Why? I presume it’s because of the decline in the demand for diesel engines, especially in Europe, where they used to be popular. Platinum is used in catalytic converters for diesel engines, whereas palladium tends to be used in gasoline engines.

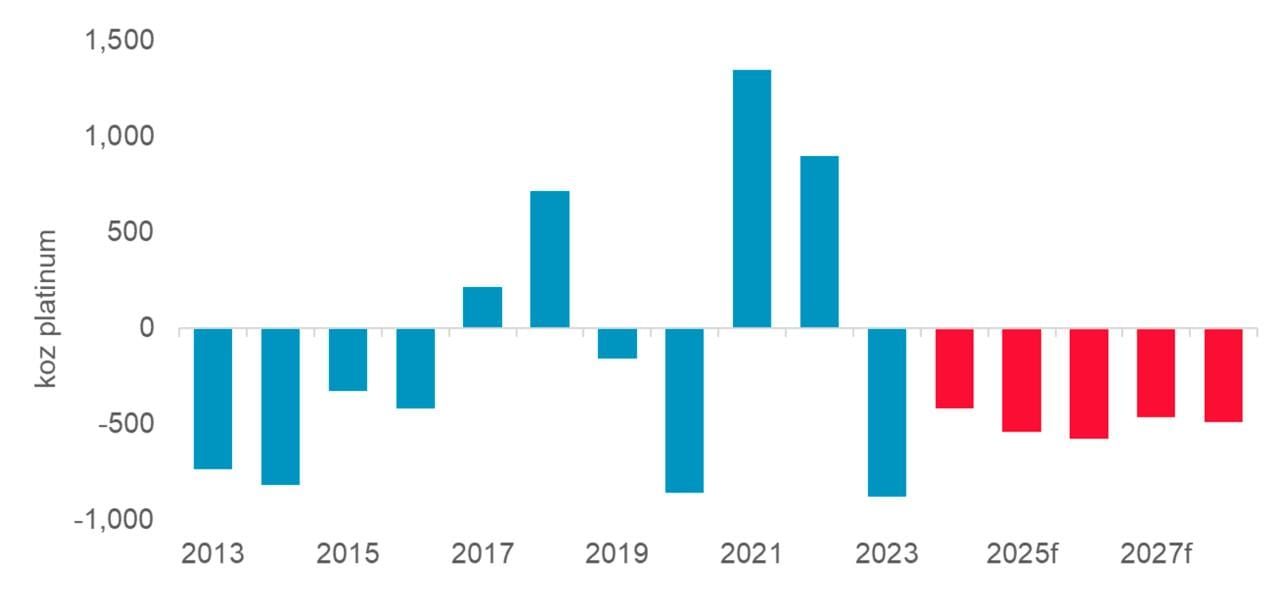

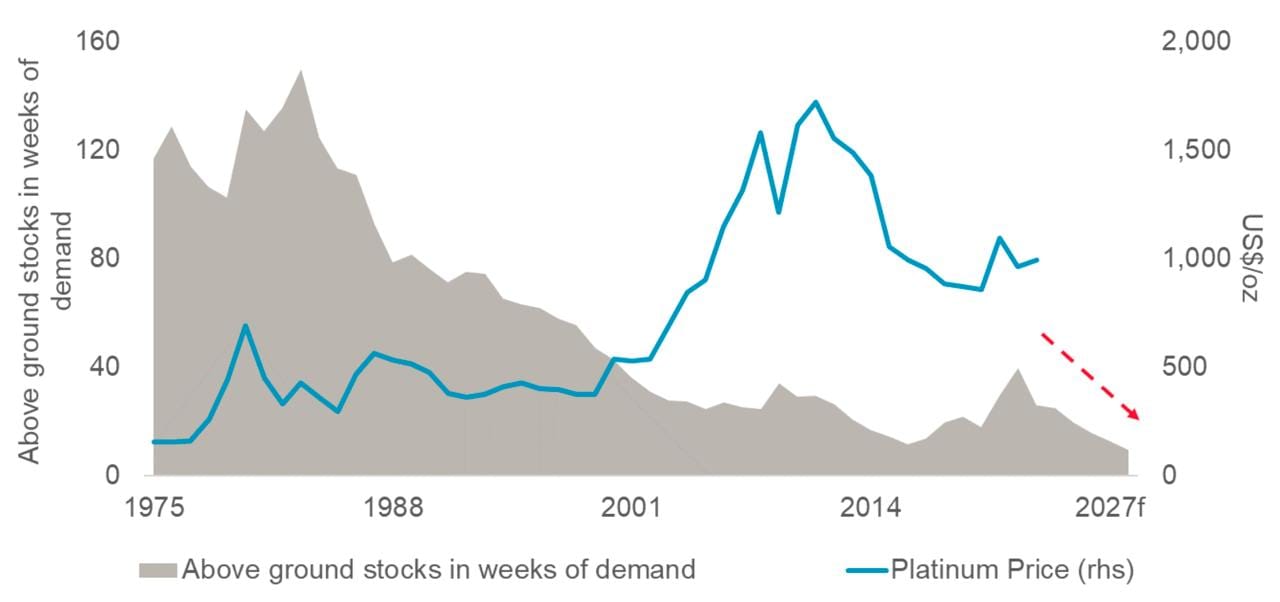

Due to a lack of new supply, PGM inventories are likely to tighten further. The World Platinum Council expects that platinum demand will outstrip supply by 6% this year, and that these shortages will persist through 2028.

Inventories are currently falling and are likely to decline by 30% by year-end 2024, according to the same source:

A representative from the World Platinum Council said that platinum prices are likely to respond at some point:

“The ongoing deficit should tighten market conditions… Ultimately we can expect this to be reflected in price expectations”

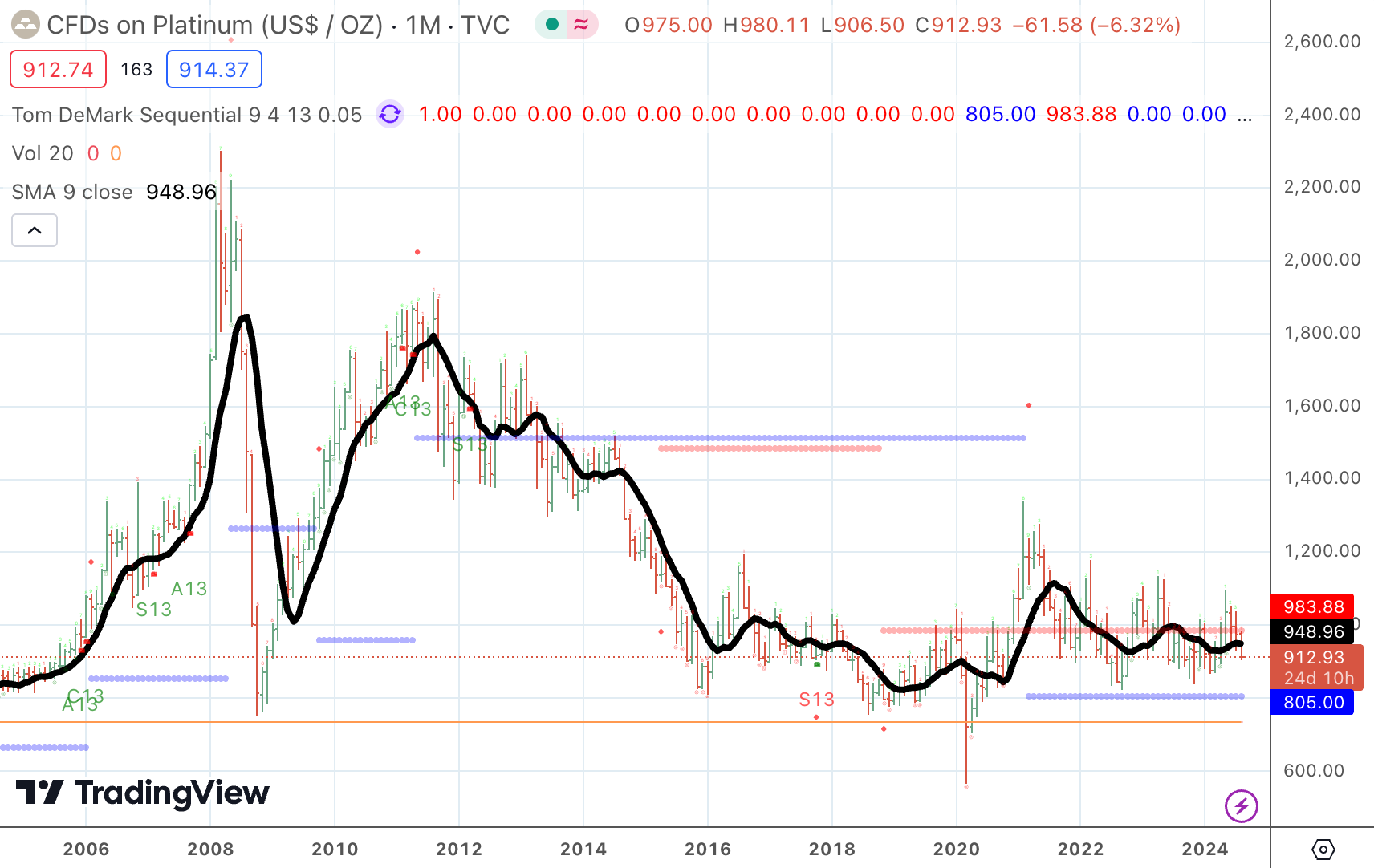

For now, platinum prices remain rangebound, as they have been since 2016:

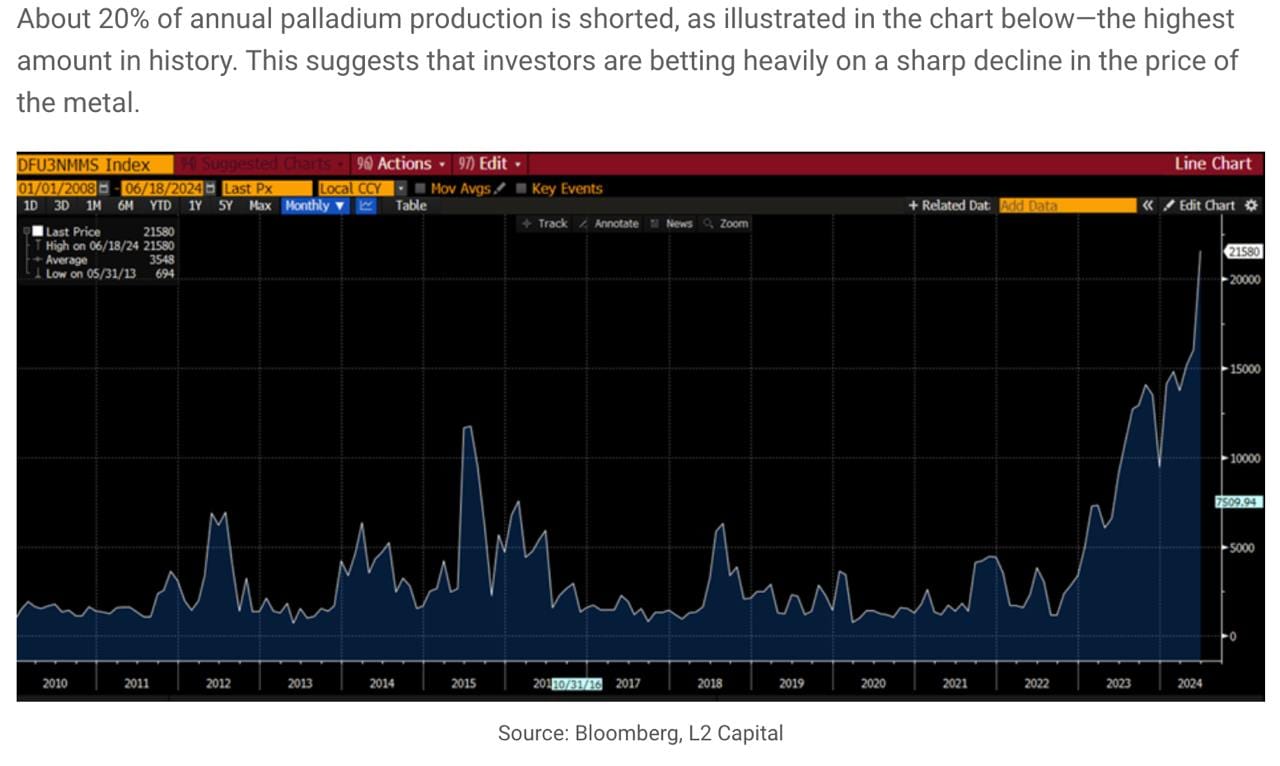

Palladium is also out of favor. Marcelo Lopez reports that 20% of annual palladium production is shorted, making it one of the most shorted metals in the world. The EV narrative has investors betting on a secular decline in palladium prices.

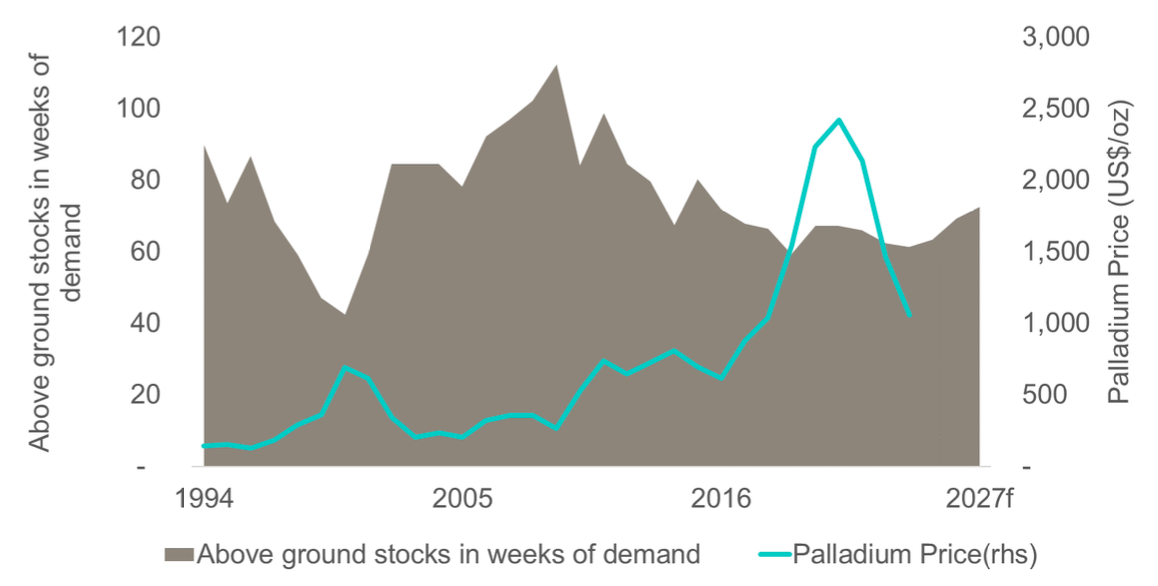

The supply of palladium is expected to be less tight, with a deficit of 1.3 million ounces this year but then flip into a surplus in 2026. Inventories aren’t nearly as tight as for platinum.

This might explain why palladium prices are still higher than their previous bottom in 2016:

The demand for catalytic converters seems to be inelastic. There are no substitutes other than among the PGMs themselves, and since there’s only about US$100 worth of platinum in a vehicle, the number could easily double or triple without really affecting the demand for a product that’s essentially become mandatory.

The only question mark, in my mind, is whether a global recession might cause the demand for industrial commodities, including platinum, to drop. The Chinese economy is weak and monetary policy in the rest of the world appears to be tight. It might be too early to become truly bullish, despite the ever-tightening supply for platinum.

4. The investable universe of PGM assets

Among the investable universe of platinum group metal assets, you’ll find coins, funds as well as mining companies focusing on these metals.

There are three major mining companies with exposure to PGMs: