Shipbuilding 101 ⚓️

The shipyard industry is cyclical and competitive. But supply has shrunk significantly while demand is picking up. Estimated reading time: 24 minutes

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

Shipbuilding is a pretty dismal industry, with low margins and vulnerability to movements in labour costs, exchange rates and commodity prices.

The supply of shipyard capacity has dropped since the last peak in 2008 and has only now started to peak.

Meanwhile, demand for shipyard capacity has improved thanks to record orders for containerships and LNG carriers.

Environmental regulation will also increase the demand for shipyard capacity, as existing vessels need to be replaced or upgraded to meet the 2050 green goals set out by the industry body IMO.

While shipyards have been burdened by rising wages and prices for steel, those headwinds are now disappearing. New-build prices have also gone up, suggesting that yard profitability is about to improve.

The Korean shipyards are well-placed to meet the demand for more environmentally-friendly and complex-to-build ships. But those stocks are trading at high multiples.

Yangzijiang and Namura Shipbuilding in Japan trade at lower multiples. The former has almost unbelievable 20%-type operating margins. Namura Shipbuilding benefits from the weaker yen and is well-placed to benefit from an uptick in tanker orders.

Meanwhile, Kawasaki Heavy Industries and Austal are well-placed to benefit from the secular trend of higher defence spending.

Table of contents

1. The basics of shipbuilding

2. How shipyards make money

3. Regulatory environment

4. Supply & demand for shipyard capacity

5. Shipbuilding industry map

5.1. South Korea

5.2. China

5.3. Japan

5.4. India

5.5. Other countries

6. Conclusion

1. The basics of shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is a simple business. Buy a piece of land next to the sea or the banks of a river. Then set up workshops, equipment and manpower to construct vessels.

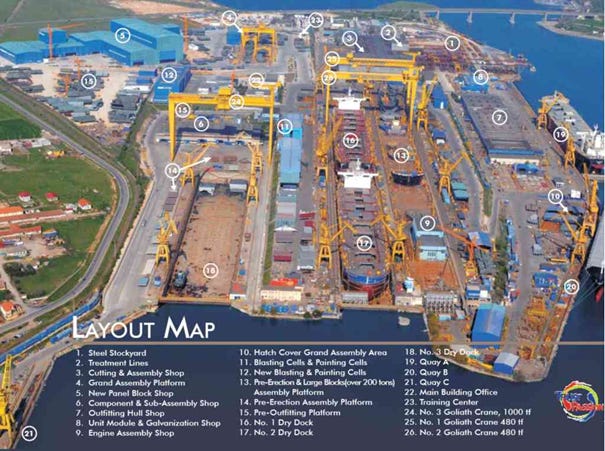

Here is an illustration of how a typical shipyard might look like, using Hyundai’s Mipo shipyard in Ulsan, South Korea, as an example:

Production of parts takes place in workshops, and final assembly is then done in either dry docks (on land) or floating docks (in water). Large cranes move parts between each section.

Here are the key steps of the process of building a vessel, most of which are mentioned in the picture above:

Cutting factory: A cutting factory is used to create steel parts, of which you typically need 50,000-100,000 for a single ship.

Assembly line: Small and middle-sized blocks are connected into large blocks, each weighing more than 400 tonnes.

Blasting and painting: These large blocks are blasted with iron powder to clean the surfaces and then painted.

Outfitting factory: Pipes and electric cables are installed to blocks such as the engine room.

Grand assembly site: This is the place where the grand assembly blocks are built by connecting large blocks from the assembly lines.

Dry dock: This is where the hulls of the ship are constructed from the grand assembly blocks. Dry = on land.

Float-out: Finally, the vessel is put into the sea by raising the water level in the dry dock - a so-called “float-out”. The ship is then delivered to its new owner.

The amount of work needed to build a ship is usually measured as compensated gross tonnage (“CGT”). You calculate the CGT by taking the cubic feet of the ship’s internal value and then adjusting that number with a coefficient based on the additional workload required to build a particular ship.

For example, the internal spaces of a passenger ship are far more complex than those of a dry bulk carrier, and their coefficients will therefore differ. Any unit of CGT will be roughly the same in terms of the workload needed to be done by the shipyard.

Deadweight tonnage (“DWT”) is a completely different metric. It instead measures what weight in tonnes a vessel can carry.

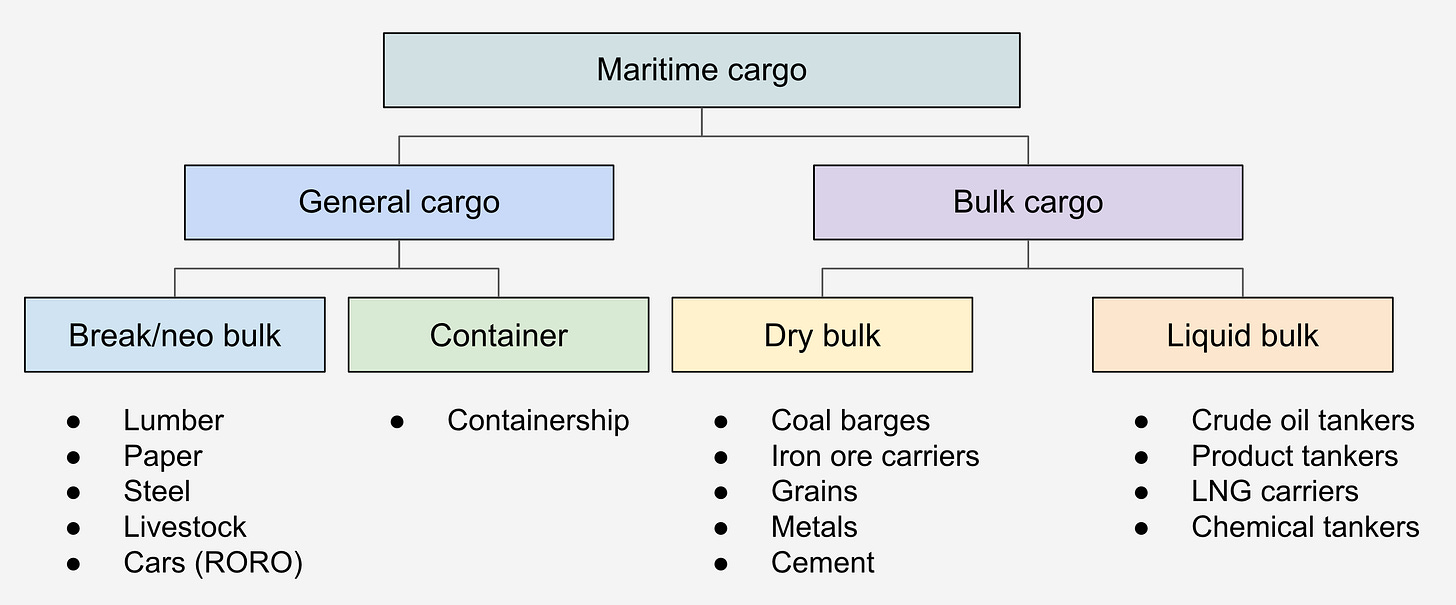

Here are the main types of ships that are typically built by shipyards:

Cruise ships, ferries, yachts and motor- or sailboats are included in the passenger boat- or passenger ship category. The general cargo category includes containerships and so-called break bulk ships such as roll-on-roll-off (for passenger vehicles), reefer vessels (refrigerated for transport of fruits, etc.), livestock vessels, etc. In the bulk cargo category, you’ll find dry bulk ships used for commodities such as coal, iron ore etc., and tankers used for the transport of crude oil, LNG, etc.

The complexity of construction between these ships differs greatly:

For example, dry bulk carriers or tankers are among the least complex of larger ships. The competition among shipyards for these types of orders is, therefore, significant.

At the other end of the spectrum, military vessels, LNG carriers or cruise ships are more complex to build and therefore produced at specific first-tier shipyards.

Since shipyards need to be close to water, they will be located along the shorelines in locations with greater water depth.

Today, most commercial shipyards are assembled in the Eastern part of the world. The major shipbuilders today are China, Korea & Japan, as rising labour costs have made shipyards elsewhere uncompetitive. European companies still dominate the cruise ship and yacht industries, as those tend to be complex to build.

State-owned shipyards tend to get a greater share of defence contracts. But they’re generally also worse run and often stupid about returns on capital. Private shipyards dominate the construction of higher-end, more technologically advanced vessels.

And then there’s a question of new builds vs repairs. Some shipyards focus only on new builds. Others are also engaged in the repair or upgrading of existing vessels. Finally, there’s the ship-breaking industry, which involves disassembling vessels by individuals who have experience working with hazardous materials.

In this post, I’ll focus almost exclusively on the commercial new-build market.

2. How shipyards make money

Shipyards take orders from customers such as shipping lines that want to expand capacity. If a shipyard has the capacity, it then proceeds to build the ships according to specifications.

Ships are typically priced on a cost+ basis, with EBITDA margins of 5-10%. Here are the average EBITDA margins for shipbuilding companies between 2001 and 2015. They’ve trended lower over time due to competition from China. The below chart also shows the cyclicality of the industry, with cycles lasting up to a decade or more.

Ships are usually priced in US Dollars. The major expenses for a shipyard are raw materials and labour, in that order. In East Asia, the cost of labour is typically around 20-30% of the total manufacturing costs of a ship. This means that:

A drop in a country’s currency - and resulting lower US Dollar wages - can have a major impact on a shipyard’s profitability

Equally, sudden increases in wages can cause existing projects to become unprofitable, especially if the contracts don’t allow for wage adjustments.

If prices for raw materials - especially steel - go up more than expected, margins will be squeezed as well.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asian Century Stocks to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.