Book review: Handbook on the Psychology of Pricing

On Markus Husemann-Kopetzky's new book. Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

In the past week, I’ve been fascinated by Markus Husemann-Kopetzky’s new book Handbook on the Psychology of Pricing. The book provides examples of pricing strategies companies use to raise prices.

In this post, I argue that the pricing strategies mentioned in Husemann-Kopetzky’s book mostly revolve around reducing the risk or perceived pain of purchase, making customers feel like they’re getting a good deal or being part of a community.

At the end of the day, if you can make customers feel positive about a purchase, chances are you’ll also be able to raise prices.

Warren Buffett popularised the term economic moat, which he defines as competitive advantages that protect a business from competition.

The theory goes that if the economic moat is strong, the company will have bargaining power against its customers and be able to raise its prices.

In a speech, Buffett spoke about pricing power in the following way:

“If you've got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you've got a very good business. And if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price by a tenth of a cent, then you've got a terrible business. I've been in both, and I know the difference.”

But the question is, how can we assess whether a company has the ability to raise prices? Is it all about bargaining power?

A new book by researcher and former management consultant Markus Husemann-Kopetzky called Handbook on the Psychology of Pricing argues that companies can use a variety of tricks to raise prices without much pushback from consumers. He believes that pricing is as much about psychology as it is about about, say, the industry structure.

I’m inclined to agree. In some cases, like with Microsoft Windows, there’s no clear alternative, and the company can raise prices without much pushback.

But for other companies like Costco, it’s not as clear that its products are differentiated. Instead, they’re forced to use clever pricing strategies to make their customers willing to spend.

In this post, I will discuss Markus Husemann-Kopetzky’s book on the strategies that companies use to raise prices. And I will make the case that, on a fundamental level, these strategies tap into our emotions.

You can then think about these strategies when you 1) judge whether a company’s new products or services will be successful and 2) assess whether a management team is skilful in setting prices and helping their company earn a return on its capital.

Table of contents

1. Introduction to pricing theory

2. Chasing dopamine

3. Avoiding pain

4. Feeling you’re part of a community

5. Conclusions1. Introduction to pricing theory

The traditional theory of pricing is that demand curves - the relationship between volume and price - are downward sloping. In other words, that a low price leads to high demand and that a high price leads to low demand.

However, studies show that many demand curves look nothing like the typical model. Instead, they have a variety of shapes that traditional economics has found difficult to to explain:

Psychological biases are the determining factors behind these demand curves. For example:

Customers may demand a minimum price to avoid the risk of buying counterfeits

They may prefer to buy expensive luxury goods to signal status to their peers

In many cases, customers are indifferent as to whether a widget costs $2 cents or $3 cents, because the price is low compared to their overall budget

The levers that companies can pull to increase prices include prices, payment, the context in which the product is sold, various nudges and other techniques to create wanted outcomes.

2. Chasing dopamine

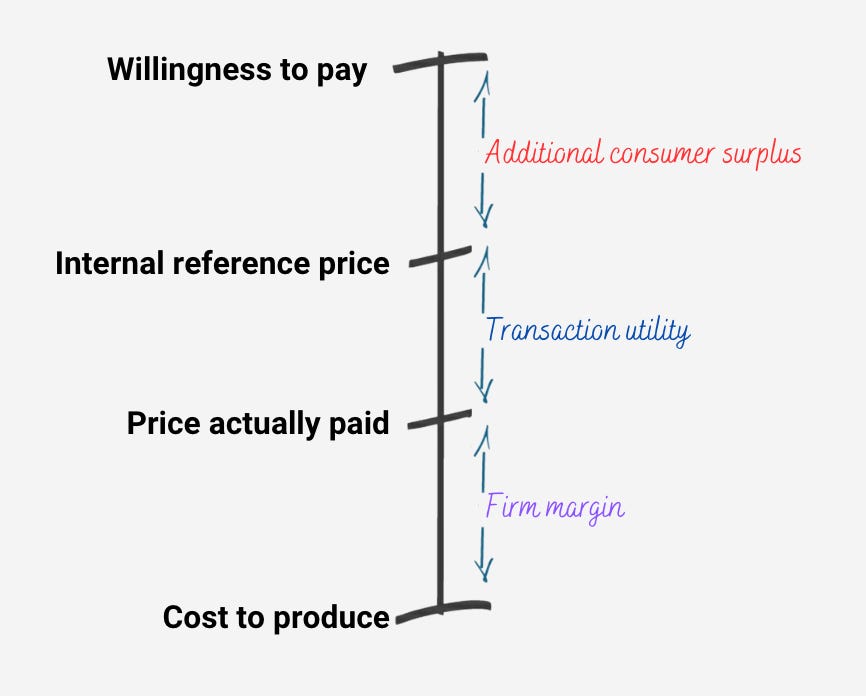

Have a look at the following chart, showing a price scale from high to low:

A customer’s willingness to pay is the maximum a company can charge for its products. And the company’s willingness to sell is the minimum that it accepts. Where the actual price ends up between these two extremes determines company profit and the “customer delight” - or, in economic parlance, consumer surplus.

But are the willingness to pay and the price paid the only factors determining how we feel about a transaction?

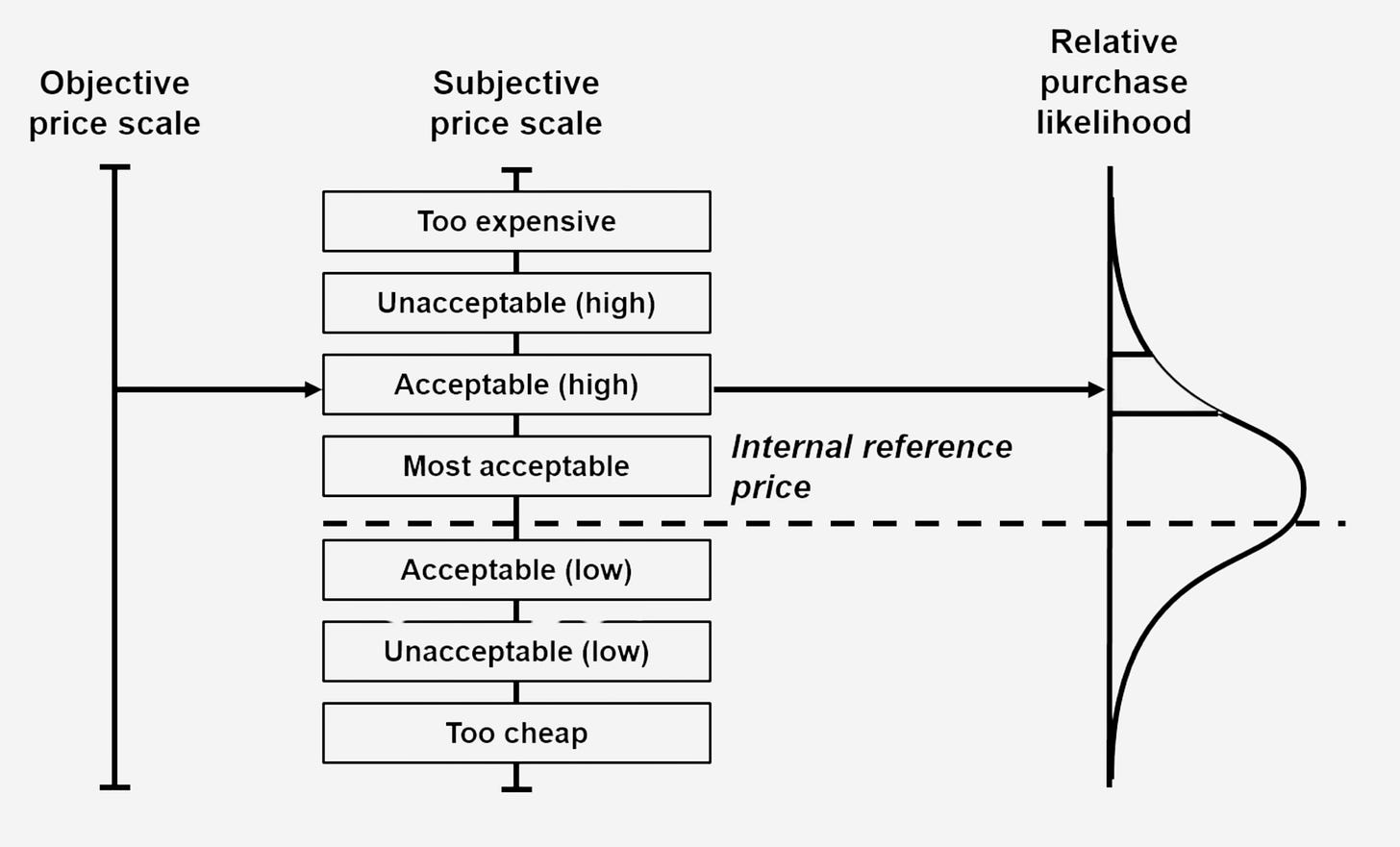

Probably not. In 1973, Professor KB Monroe argued that how we feel about a transaction concerns perceived fairness. Experience tells us that a product should cost around a certain price level. And if the price is too high or too low in comparison to this price - which he called the internal reference price - we’d feel cheated.

An example might illustrate what this concept is about. Let’s say you’d be willing to pay $4,000 for an iPhone. That’s how much your iPhone is worth to you. But you also know that a normal iPhone costs around $1,000. So if a seller asked you for a higher amount, you’d feel cheated. In this example, $4,000 is your willingness to pay, and $1,000 is your internal reference price.

In 1985, psychologist Richard Thaler coined the term transaction utility, referring to the value you gain from the transaction. In technical terms, that would be the difference between your internal reference price and the price actually paid. In our iPhone example, if we pay $950 for our iPhone that we feel should cost $1,000, then we enjoy transaction utility of the difference between the two numbers: $50.

My main point is this: consumers are partly driven by wanting to make good deals. The rush of dopamine they feel is not just about getting value out of the product; it’s also about feeling good about the transaction itself.

From that perspective, companies should try to raise internal reference prices as much as possible so that customers feel they’re getting good deals. If they can make us think an iPhone is worth $1,200, we’ll feel even better about our $950 purchase.

The most common method to increase internal reference prices is through association. For example, Nike has used sponsorships with athletes to make customers feel like they’re buying something special. IKEA markets itself as a Swedish brand, as it knows the country has a positive image in most parts of the world.

Then there’s this psychological concept called anchoring, whereby consumers get influenced by whatever arbitrary number you present.

So companies can expose them to any high number, even before they get a chance to evaluate the price. Almost without fail, they’ll start thinking that the price offered is not too bad after all.

This is the purpose of stating manufactured suggested retail prices (MSRP) in an advertisement. Then, offer customers discounts from this MSRP so that they feel they’re getting a good deal.

Companies can also make the price paid seem lower than what it is. People typically purchase more of a product costing $1.99 than $2.00. The reason is that “99” is associated with discounts, so we think we’re getting a good deal. Also, we read from left to right and “1” feels materially lower than “2”.

Just be aware that discounts and “99 prices” can also devalue the product in the eyes of consumers. A perception that the product can only be sold at a discount will eventually lower consumers’ internal reference prices.

You could well argue that internal reference prices are more easily determined for utilitarian products such as consumer electronics. Their performance can often be quantified to the nth degree. Discounting such products will not hurt too much.

But when it comes to emotion-driven purchases such as perfumes, flowers, luxury watches and sports cars, consumers have no idea what they could be worth. When it comes to internal reference prices, the sky is the limit. And for such products, it’s best to avoid any perception of discounting.

Here are some other ways that people can perceive a price to be lower than it really is:

Taking off the cents from a “$2.00” price into “$2” makes the price look smaller

Taking off the comma sign of a number with four characters or more, e.g. “1,000” to “1000”, makes it seem smaller

A smaller font size helps drive home the point that the price is low

A discounted price in a different colour drives home the point that it’s different

Stating prices as a unit per time makes it seem smaller; e.g. instead of “$10 per month”, you can state the price as “$0.30 cents per day.”

Quoting the price as a series of instalment payments makes the price seem lower.

The presence of a sale sign makes prices seem lower than what they are

High numbers sound more impressive, so consumers, for example, will prefer a 50% bonus pack to a 35% discount.

Companies also use the phrasing “save up to x%” to make discounts seem larger.

Professor KB Monroe also found that consumers don’t react much to small price differences. He coined the term just-noticeable difference. Empirical evidence shows that prices need to go up at least 6-10% before we start noticing the price change. And conversely, a discount probably needs to be higher than 6-10% for people to feel like it’s material.

In any case, shopping is a game. And don’t be fooled into thinking that the act of consumption purely drives consumers. In many cases, we buy because we enjoy getting good deals. In other cases, we see purchases as a route to self-actualisation. We want to feel like we are making progress. Collectors will often tell you that they’re driven by the “thrill of the chase”, driven by the ups and downs of dopamine in their bodies.

So companies need to consider that when setting prices and making customers feel good about their purchases.

3. Avoiding pain

Israeli psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky developed prospect theory, a framework that predicts how people derive value from purchases.

In simple terms, prospect theory says that the utility you get from small gains is lower than the negative utility you experience from losses. In other words, losses hurt more than gains make us feel good.

Kahneman and Tversky performed studies that proved this theory in quantitative terms. Losing $10 has as much of a negative impact on our brain as winning $25 feels good.

This has important implications for pricing. In setting prices, companies will want to change reference points to see fees as gains rather than losses, for example, instead of saying that a credit card company adds a surcharge. You can turn the whole argument around and say that paying by cash enables a discount. That framing will feel a lot better for consumers. Or by emphasising the positive experience from consuming a product rather than its price.

I believe that a key reason why people pay for certain products is to lower the risk of a poor purchase. Our willingness to pay is especially high when we can’t determine the quality of the product and the risk of a faulty product is high. That’s why we don’t mind paying extra for clean food or brand-name medicine.

And since we know that established brands have incentives to keep their quality control high, we rely on brands to lower the purchase risk. This is where brand pricing power comes from.

The fact that consumers infer quality from high prices means that setting prices too low might cause them to be sceptical. Research shows that people seem to think that low-priced wine tastes worse, even though it’s identical to a higher-priced wine in a sample.

Another way to lower the purchase risk is by going with compromise options. By choosing the middle option, we feel we’re not going towards any particular extreme, thus reducing risk.

This effect is particularly strong when consumers must justify their purchases to a third person. As they say, “Nobody ever got fired for choosing IBM”.

This fear of future regret also explains why we buy insurance and like money-back guarantees. Most of us know that AppleCare does not make sense purely financially, but we’d hate to end up in a position where our phones break down and need expensive repairs.

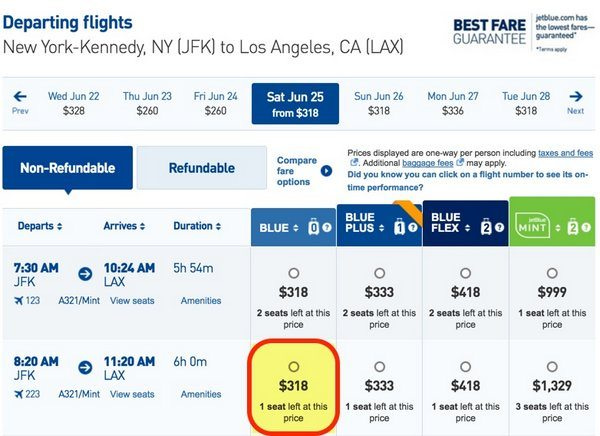

I think the potential pain of future regret also influences our preference for scarce products. We feel that if we don’t buy the product now, we might miss out on it in the future. Companies often play up the scarcity factor by stating that the product can only be purchased today or that only a few items are available.

Of course, scarcity can also provide a quality cue. Because if inventory is running low, others must see value in the product. And perhaps you should see value in it, too.

The fear of future regret also plays a part in the success of Uber. Consumers much prefer fixed rates to variable rates that depend on usage, like taxi meters. This flat-rate bias seems to be because people don’t want uncertainty and potential surprise losses.

You can also reduce the pain associated with a payment by changing the payment option. It’s been shown that by paying with credit card instead of cash, consumer willingness to pay goes up by 100%. And that’s also true for Apple Pay. The friction goes away. And that’s even more true for airline miles and loyalty cards, almost seen as monopoly money.

Finally, consumers hate exerting effort. They generally do not want to spend time researching the advantages and disadvantages of a particular product and instead rely on heuristics to go about their days.

Companies are well advised to use prices and discounts that they can deal with easily. For example:

Show savings after the price since that’s how they typically perform subtractions.

When division takes place, use divisible numbers, i.e. not prime numbers.

Instead of discounts, tell them what the revised prices are so that they don’t have to perform any computation.

To summarise, lowering the pain of purchase is worth a lot. Raising the internal reference price will help. But also taking away transparency and friction in the payment process, lowering the risk of uncertainty through brands and reducing the risk of future regret through money-back guarantees and warranties.

4. Feeling you’re part of a community

Robert Cialdini’s studies quoted in his book Influence showed the power of reciprocity. This means the practice of exchanging things with one another for mutual benefit.

Cialdini points out that if someone does something for us, we feel indebtedness to that person. And we then feel compelled to return the favour given to us.

So from a company’s point of view, you’re well advised to give a gift or a warm welcome. The consumer is then more likely to spend money in return.

Given this strong tendency to return favours, companies should consider essentially giving away products for free instead of charging a low amount. Free perfume samples in magazines are one example. But the same is true for free trials for online subscriptions, where readers feel like they’re getting something for free. And they’ll probably be more likely to become fully paid subscribers.

This tendency towards reciprocity is tightly connected with a need to feel like we’re part of a community. The consumption of certain conspicuous products such as smartphones, wristwatches and handbags is tightly connected with a sense of belonging to certain groups. In other words, by purchasing a product, you confirm your identity as part of that group.

Scarcity plays a part here as well. Limiting the supply of products makes it seem like we’re a part of an even more exclusive club. To buy a Rolex today, you’ll need to be on a waitlist for years before getting the opportunity to pay the full retail price. And once you finally get your Rolex, you bet you’ll value it higher than you would have otherwise.

5. Conclusions

The pricing strategies in Markus Husemann-Kopetzky’s book revolve around reducing the risk or perceived pain of purchase and making customers feel like they’re getting a good deal or being part of a community.

I don’t believe a company needs one of Morningstar’s 5 economic moats to be valuable. I think pricing is partly about bargaining power, creating positive emotions, and avoiding negative emotions across the customer journey.

Many highly successful companies, such as Lululemon and Crocs, sell commodity products, yet they continue to be highly successful at what they do. Their ability to raise prices has nothing to do with barriers to entry but rather clever pricing strategies that make everybody feel better off after the transaction.

Makes me wonder how long it takes for internal reference prices to adjust in an inflationary environment like the one we are facing now. An example from my everyday life, a few restaurants that I frequent have raised prices above my internal reference rate. I feel like I am not getting good value for my money. Probably I will have to adapt my IRP at some point.

"all for the price of a few cups of coffee per month" I wonder where the inspiration for this came from?