Post-war Germany's lessons on inflation

A summary of Bresciani-Turroni's book The Economics of Inflation. Estimated reading time: 24 minutes

Costantino Bresciani-Turroni was an Italian economist that lived between 1882 and 1963. He’s famous for being an anti-fascist intellectual and a proponent of free-market economics.

But more importantly, he wrote a book called The Economics of Inflation, which is widely regarded as the definitive book on Germany’s experience with hyperinflation between 1919 and 1923.

Bresciani-Turroni spent most of his life as a professor. But after teaching statistics at the University of Palermo and Genoa, he was recruited by the Italian Ministry of Affairs as a delegate to the Reparation Commission to Germany. The Allied forces of World War 1 punished the German people for sparking the war and demanded reparations from the Allied nations for the destruction caused. These reparations were established through the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919, and Bresciani-Turroni was part of the apparatus meant to collect the reparation payments.

I read the book over the past week to get an insight into how inflationary pressures propagate through an economy. As well as how individuals and policymakers respond to it.

It’s a challenging read but ultimately worthwhile for those who want to understand the causes and effects of inflation. And how investors can protect themselves should Germany’s hyper-inflation ever repeat.

1. The post-war German experience

1.1. The First World War

The first World War broke out on 28 July 1914 when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Germany joined the Austria-Hungary coalition. And on the side, Russia, France, the UK and the US formed the Allied forces of World War 1.

Just three days after the start of the war, the German central bank (“the Reichsbank”) suspended the conversion of its notes to gold. The German currency (“the mark”) became paper money without any value anchor. It, therefore, became known as the “paper mark”, as opposed to the previous, gold-backed “gold mark”.

The reason behind the suspension was that the government knew that it would be unable to finance the war through tax revenue. Instead, the Reichsbank took it upon itself to print money to cover any deficit. And in the following four years, the Reichsbank routinely bought government bonds used to finance the budget deficit.

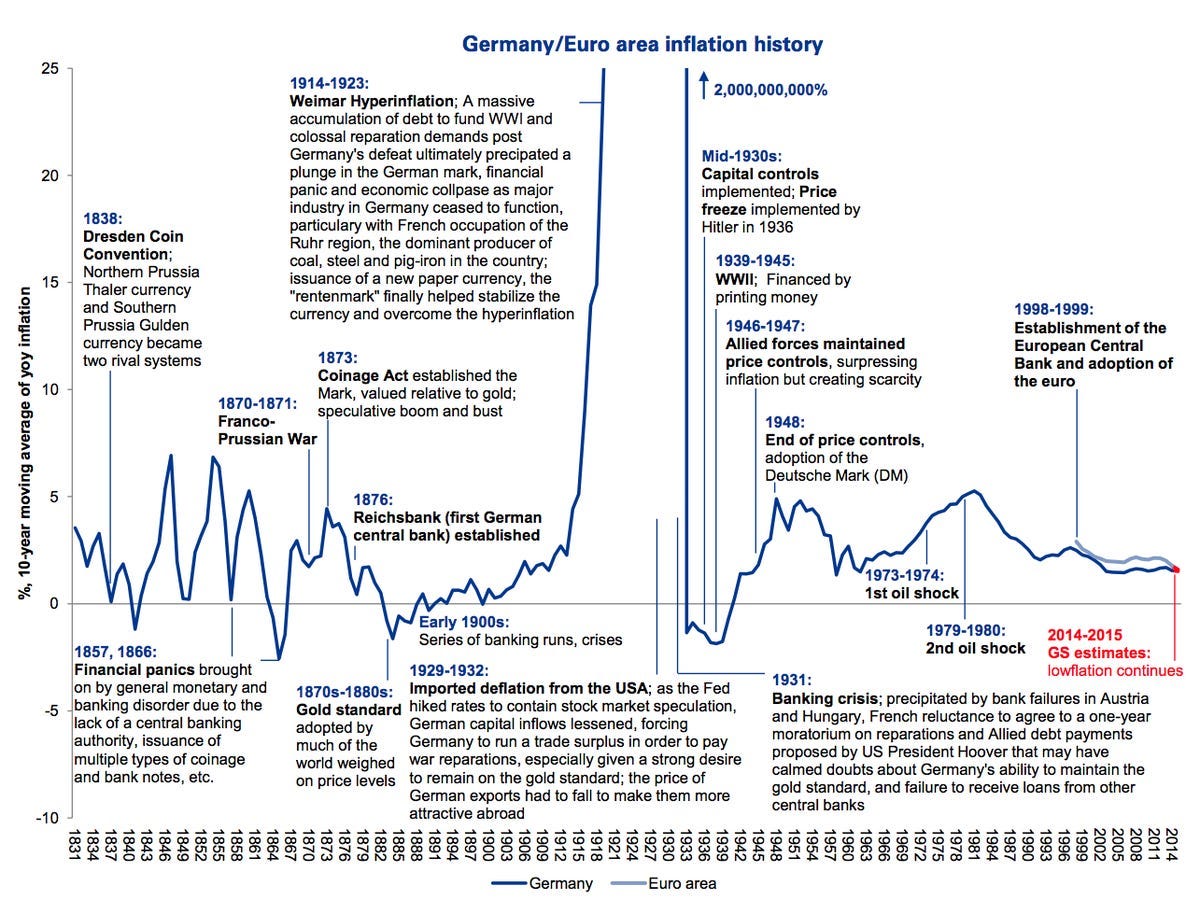

The depreciation of the German mark during the war was slow. By the end of 1918, 1.57 paper marks were worth roughly 1.00 gold marks, suggesting a depreciation of just 57%.

But this stability in the exchange rate masked a more serious “internal devaluation”. The money supply grew over 400%, driven by rising government debt. Domestic prices more than doubled, despite price controls.

From July 1914 to the end of the war in December 1918, Germany’s total government debt rose from 300 million marks to 55 billion marks. The war cost roughly 147 billion marks in total, and so more than 1/3 of it was financed through government borrowing, much of it financed through central bank support.

A contributing factor to the stability of the exchange rate was the fact that the government had asked citizens to surrender any foreign securities to the government in exchange for the paper mark. That helped create buying pressure and keep the currency from depreciating.

There were also clear signs of German hoarding of paper money to evade taxes. Some individuals believe that the paper mark would increase in value after the war. They thought that the fall in purchasing power was simply due to the war and that once it was all over - prices would fall, and the mark would regain its pre-war gold parity.

That optimism would prove to be unfounded.

1.2. The post-war years

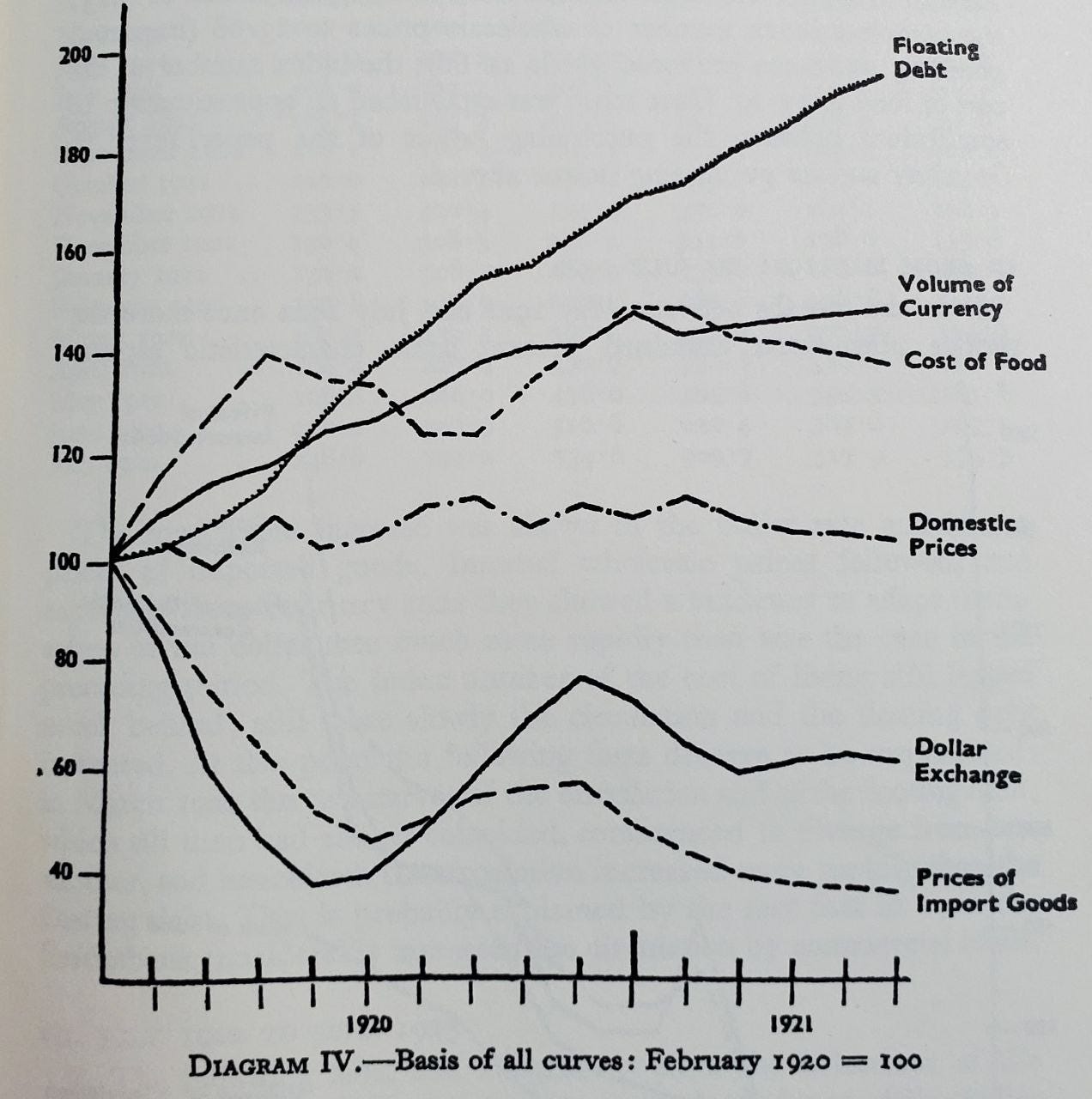

The war ended on 11 November 1918 with a German surrender, driven by a new German civilian government. From then onwards, the exchange rate started to depreciate rapidly - faster than domestic prices and the volume of circulation.

There had been hopes that a German victory would lead to spoils of war that could alleviate the country’s debt burden. But once the government declared defeat, those hopes were crushed.

In the eight months after the war ended, the budget deficit reached the 10 billion mark - an incredibly high number. when the Socialist Party took power in November 1918, it didn’t have the strength nor the ability to impose the taxes necessary to balance the budget.

The theory prevailing at the time in Germany was that the depreciation was caused by a deterioration in the balance of payments. But foreign voices and especially the British, believe that the depreciation of the currency was instead caused by an excessive budget deficit.

It’s possible that the holders of the mark feared heavy reparations payments and therefore sold the currency in anticipation of a coming crisis. The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919. The Treaty might have had a psychological influence on the German public, who feared that the government would resort to money printing to fund the deficit.

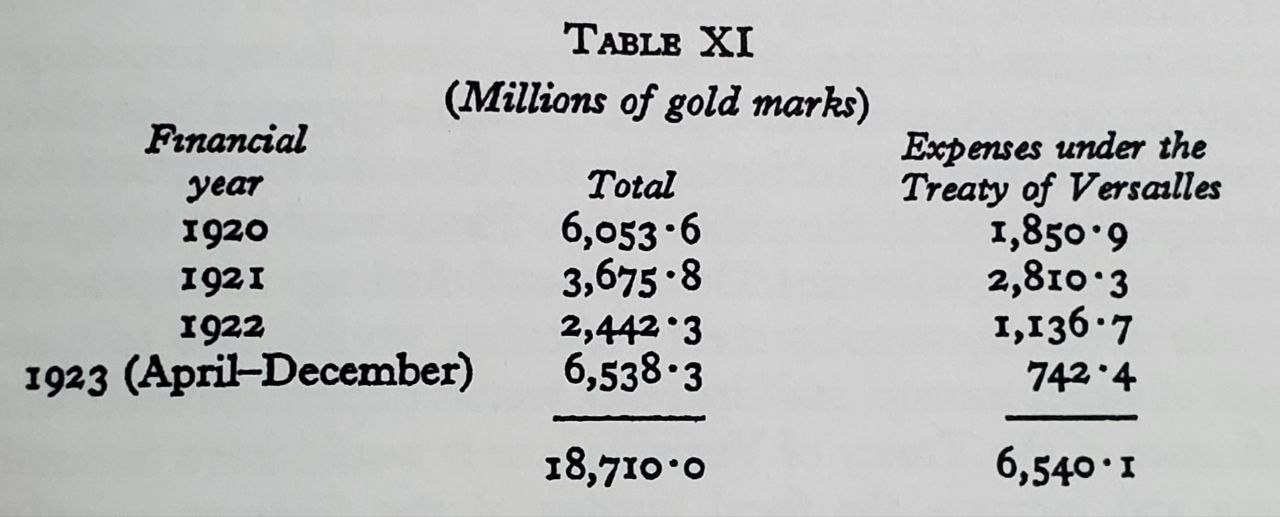

In reality, the budget deficits would have been high with or without the reparation payments. And the payments actually made under the Treaty of Versailles were not particularly onerous, representing only 1/3 of the total deficit between 1920 and 1922.

The inflation of the early post-war period also reduced the government’s debt burden since it was denominated in the German mark. In fact, the interest on the government’s previous debt far exceeded any reparation payments. In other words, the reparation payments were not the only cause of the budget deficit and probably not even the most important factor.

Later on, German propaganda used the Versailles Treaty to shift blame for the hyperinflation to foreigners, perhaps to unite the country under a new Hitler-led government. Bresciani-Turroni is convinced that it was Germany’s continued monetisation of a budget deficit that caused the money supply to balloon during those inflationary years of 1919-23.

Here is the exact process in which inflation pressures built up in the economy:

The issuance of paper money caused the currency to depreciate as speculators use the newly issued money to buy foreign currency or buy cheaper foreign goods for import.

After the currency depreciated, inflation picked up as imports - especially raw materials - became more expensive.

Later on in the process, the newly printed money worked its way through the economy and eventually led to higher wages. But wages didn’t adjust immediately - instead, they adjusted with a long lag that caught the population off-guard.

There was a narrative early in the post-war era that a weaker currency would stimulate the economy. That was true, but only to a small extent. When the currency depreciated, companies saw their profit margins increase as selling prices adjusted quickly while wages took much longer to adjust. Companies then reinvested their profits and and “fake prosperity” ensued.

Exports did particularly well since they were sold at foreign, higher prices. Inbound tourism to Germany took off. Railway charges did not increase in proportion to the depreciation of the mark, so foreigners were able to enjoy cheap travel when they came to Germany. Pure labour arbitrage industries such as shipyards also did well as wages in Germany fell compared to foreign competitors.

Meanwhile, interest rates remained low. There was a kind of yield curve control in place, with the official discount rate fixed at 5% between 1915 and July 1922, even though inflation accelerated from 1919 onwards to incredible levels.

Instead of raising the interest rate when inflation picked up, the Reichsbank restricted credit instead, favouring certain borrowers over others. It continuously extended credits to private speculators, who proceeded to use these loans to buy foreign currency and profit from the depreciation of the mark. It’s unclear how these borrowers were selected. But they appear to have had a cosy relationship with the Reichsbank - to say the least.

From late 1919 onwards, Germany’s government debt started rising significantly. The exchange rate remained stable or even appreciated during this period, showing that the money supply and the exchange rate had a tenuous relationship during this period.

1.3. The currency gets dumped in 1921

In 1919 and 1920, several new laws were formulated that shifted the fiscal system by moving the authority to raise taxes from the states to the Reich. But the assessment of these new taxes proceeded very slowly, and the budget deficit therefore ballooned. In 1920-21, the yearly budget deficit reached 6 billion gold marks, roughly 60% of total government expenses - all financed by Reichsbank money printing.

The budget deficit would have been high no matter how stable the currency was. When the mark depreciated, expenses also dropped as government salaries decline precipitously. The government debt was also inflated away to almost nothing, providing support for the budget.

In May 1921, the “London ultimatum” demanded reparation payments from Germany in either gold or foreign currency of two billion gold marks, plus 26% of the value of Germany’s exports. That sparked a run on the currency in the second half of 1921.

This was a recurring theme. The currency depreciation often came after some important political event that shifted the public’s psychology into hoarding foreign exchange. The London ultimatum was such an event.

But the fact of the matter is - unless new money was created, there would no way for the selling pressure to continue forever. The culprit behind the inflation pressure was really excess money creation and a loss of confidence, leading to bouts of currency depreciation.

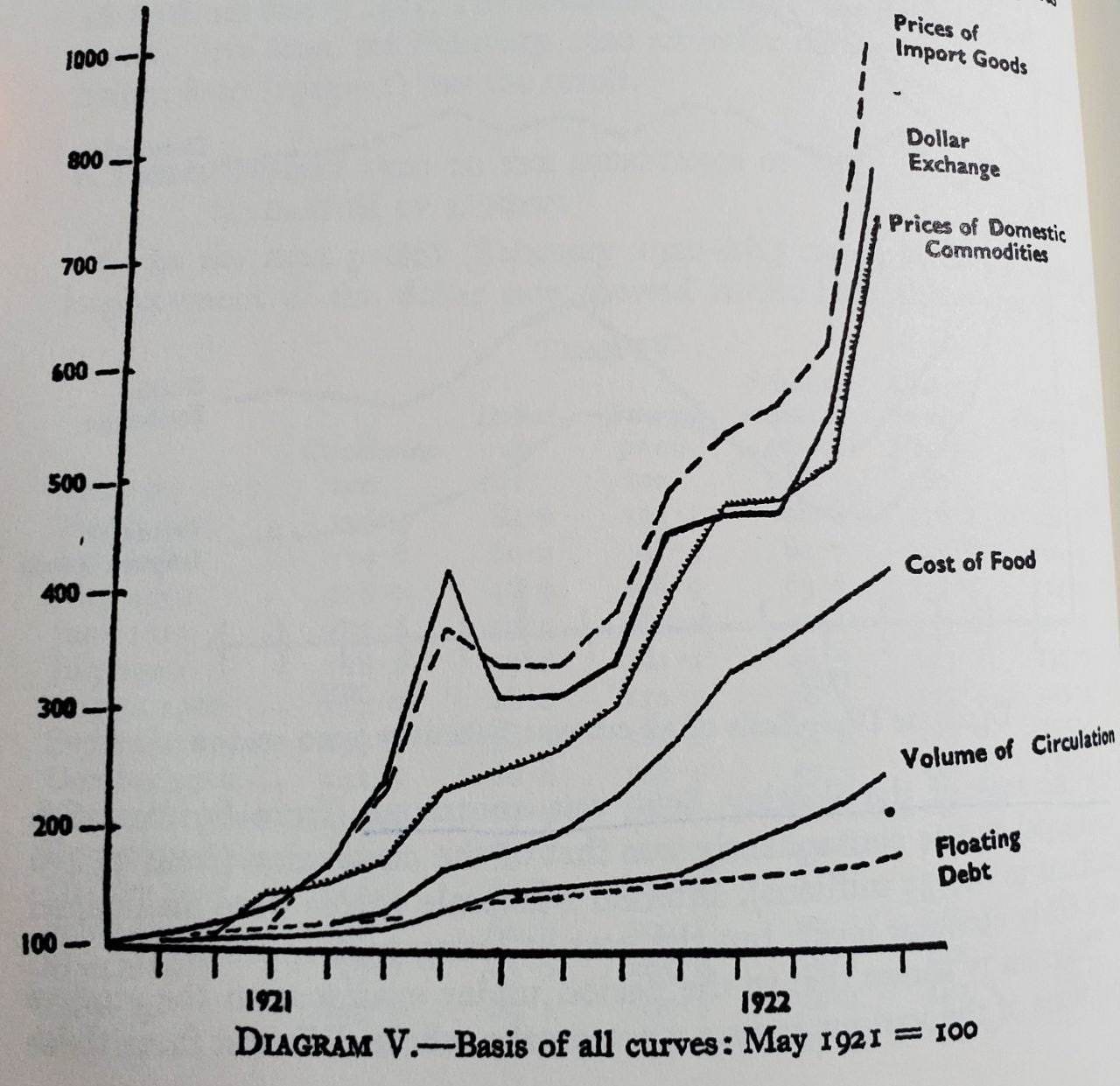

The fact that the paper mark depreciated so much more than the circulation of money in 1921-22 might come as a surprise. But as Keynes’ quantity equation (MV = PT) tells us, it’s not just the money supply that matters for inflationary outcomes - it’s also the velocity of that money and how fast it circulates.

The chart below shows that the velocity of money shot up in mid-1922, suggesting a total drop in confidence in the currency.

As individuals started dumping their paper mark for foreign currency and spending it as quickly as possible, the velocity of money shot up. The German population started living day-to-day without keeping any cash reserve. As described in the book.

“Business has reached a maximum of intensity. Buyers care nothing about prices. There is a general rush for goods.”

There was a clamour for what Germans called “material values”. As a local writer observed: “the savings of entrepreneurs were crystallised into iron and stones”. Entrepreneurs tried to protect their purchasing power by buying whatever they could get their hands on, including machinery, raw materials, etc.

1.4. Stock market booms and busts

On 12 October 1921, the government imposed limits on the amount of foreign exchange any individual could buy. Panicking, the population instead turned to stocks to help protect their capital. That led to a stock market boom in the last few months of 1921.

Initially, there was scepticism about the rise in stock prices:

“Expressed in paper marks, the prices of shares seemed very high. This exercised a psychological influence on the great mass of shareholders. Deluded by the apparently high prices, even the most cautious shareholders were induced to sell their securities; and only much later, when the veil of inflation had been torn aside, did they realise that they had made a very bad bargain.”

Eventually, though, people started realising that higher stock prices were a natural reaction to a depreciating currency. They served as inflation hedges. As share prices continued to rise, bit by bit, the entire country got swept up in speculation:

“To-day there is no one - from lift-boy, typist, and small landlord to the wealthy lady in high society - who does not speculate in industrial securities and who does not study the list of official quotations as if it were a most precious letter.”

Speculators in late 1921 felt that buying shares had saved them from the losses experienced in the depreciation of the mark in the 1919-20 period. Many believed at the time that buying shares were less risky than possessing foreign money.

But then, every sudden depreciation in the mark shifted the attention to the foreign exchange market again. While the foreign currency was hard to get a hold of, it was not impossible. A lack of confidence in 1922 led to the panic in the stock market that sent shares lower yet again, reaching almost unfathomable prices.

To get a sense of how cheap German stocks became at the bottom in 1922, the market cap of car maker Daimler of 980 million paper marks was worth no more than the value of 327 of their own cars. Fashion retailer Tietz was valued at the price of 16,000 suits.

Author Bresciani-Turroni constructed an index of 300 industrial companies on the Berlin bourse and calculated their share prices for the period 1918 to 1923. Here is a representation of that index, measured in both paper mark terms (red) and foreign currency terms (green).

You can see from the chart that their prices increased exponentially in paper mark terms towards the end of 2023. But in US Dollar terms, the index fell precipitously after the war, from an index of 100 to less than 10 in 2020.

And then, in late 1922, when the German public dumped their paper marks, the index fell down to 2.7 at the lows before recovering to 39 at the end of 1923 - a 14x gain from the bottom.

Why did share prices drop so much from 1918 to 1922?

They had enjoyed heavy war profits. Those war profits did not continue after 1918. In fact, aggregate profits experienced after the war were lower than those realised before and during the war.

There was widespread fear of the new socialist government and their plans to tax industrialists. Fear of Bolshevism made many capitalists sell their shares at dirt-cheap valuations.

Because of the lag in dividend payments and the zeal of industrialists to reinvest their capital in fixed assets, actual dividend payments amounted to almost nothing. An investigation by Industrie- und Handels-Zeitung showed that 120 companies had paid dividends equal to 0.25% of their average share price in 1921. One company paid a dividend in 1922 equivalent to just four bottles of mineral water vs 2,800 bottles before the war.

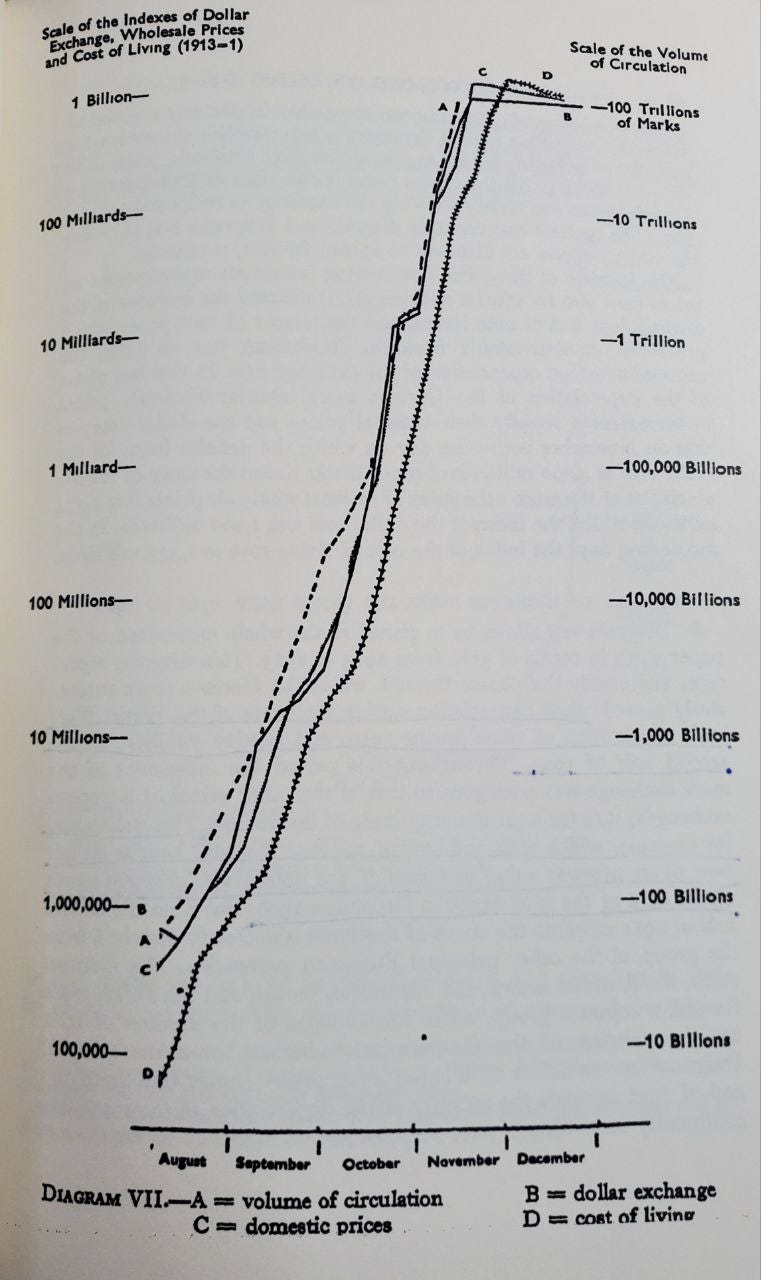

1.5. Towards hyperinflation in 1923

The hoarding of foreign exchange became more serious throughout 1922. German industrialists formed the habit of leaving the profits they made from exports overseas. Germans began to sell houses, land, securities - anything really - to get hold of foreign currency.

Eventually, Germans started using foreign exchange for their day-to-day transactions. Merchants began to set prices in the gold mark or foreign currency. While salaries were still paid in paper marks, wage earners would rush to buy goods as soon as they received the money. Or convert the money into foreign currency as soon as possible.

In February 1923, the Reichsbank tried to support the mark exchange rate artificially through foreign exchange operations. But continuous issuance of paper money caused inflation to continue, and by April, the dam finally broke with the mark being dumped at a record rate.

Workers came up with solutions to the inflation problem by adding surcharges for the depreciation of the currency added onto wage contracts. Wages became tied to cost-of-living indices.

Eventually, Germans started using foreign exchange for their day-to-day transactions. Merchants began to set prices in the gold mark or foreign currency. While salaries were still paid in paper marks, wage earners would rush to buy goods as soon as they received the money. Or convert the money into foreign currency as soon as possible.

It was only in 1923 that hyperinflation got out of control. Taxes were inflated away to almost zero since they were paid with a long lag and tax receipts ended up being only represented 0.8% of government expenses. The rest of the government’s tax revenues came from printing money. By the end of 1923, 75% of all government bonds were held by the Reichsbank.

People suffered badly during the most intense period of hyperinflation, especially in 1923. Children became underweight, tuberculosis spread, there was malnutrition, lack of house maintenance caused them to fall into disrepair, women had to join the workforce to support their families, and there was a rise in suicides. While consumption of pork declined, eating dog flesh became more common, up 6x between 1921 and 1923.

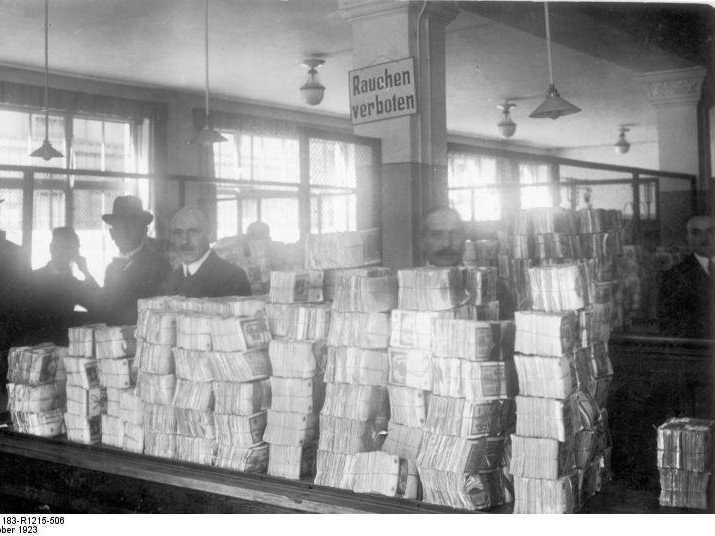

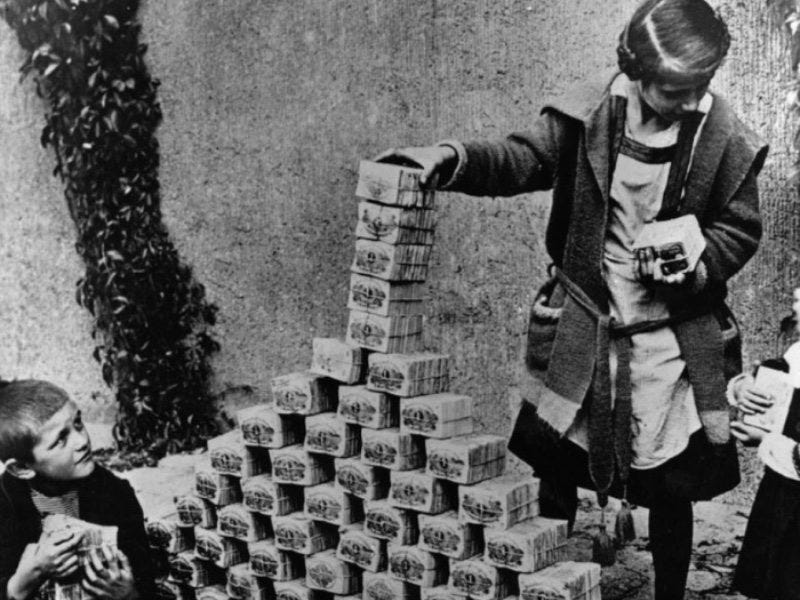

A loaf of bread in Berlin that cost around 160 Marks at the end of 1922 cost 200 billion marks by late 1923. Children started using paper mark bills as toys since they became almost worthless in terms of the purchasing power they provided.

1.6. Winners and losers in the upheaval

It’s wrong to think that the inflation period led to wealth destruction the board. The concentration of wealth increased, and some became rich in the process:

Industrialists saw their profit margins expand as wage increases lagged selling prices. Many of Germany’s greatest companies cleverly borrowed as much as they could to invest in fixed assets, then resold those same assets at a high price after the loans had inflated away. Industrialists were also able to gain access to foreign currency and even trade goods across the border. Their fiscal burden was also lightened through inflation. Industrialists with access to foreign currency were also able to purchase German shares cheaply around the bottom in 1922, increasing the empires in the process.

Speculators emerged with their own “finance companies” that aimed to take advantage of the ongoing inflation. They borrowed heavily and purchased foreign currency or physical goods. They also engaged in the import-export trade to buy or sell assets where they were most attractive based on the prevailing exchange rate.

Farmers saw their mortgages inflated away and salaries kept at a low level, while food prices rose in lockstep with the depreciation of the paper mark

Renters continued to rent their homes at old rents while their wages eventually caught up with the depreciation of the paper mark.

Among the losers were the vast majority of German workers - those on fixed wages and without the ability to speculate in stocks or foreign exchange.

Wage earners saw their real incomes drop as they lagged behind the depreciation of the paper mark. This was especially true of non-unionised employees such as professionals.

Savers who had put their money into marketable securities saw their fortunes wiped out. The “old rich” in Frankfurt and elsewhere (the so-called “rentier” class) suffered badly.

Pensioners who relied on fixed payments saw their incomes destroyed.

Landlords saw the values of their houses drop significantly as rents didn’t keep up with inflation due to the peculiarities of Germany’s housing market. High maintenance costs relative to rent forced many landlords to sell their properties at bargain prices, depressing home prices for a period of time. Their properties were often sold to foreigners looking for cheap property.

Banks saw their capital more or less wiped out. While their deposits were matched with loan assets in terms of duration and interest rates, the capital of the banks was also invested in fixed-income securities that depreciated in real terms. Banks were also obliged to keep a significant amount of mark bills and coins on their balance sheets for redemptions, and that cash depreciated in value quicker than their overall loan books and deposits.

Measured in gold marks, salaries in Germany dropped about 50% vs their pre-war levels. But the situation was even worse for the professionals: doctors, private teachers, artists and intellectuals who didn’t enjoy trade union protection and offered services that weren’t essential for survival.

1.7. The stabilisation “crisis”

On 15 October 1923, a new bank called the “Rentenbank” was created. This bank issued liabilities that were meant to be used as a substitute for the paper mark. Later that year, the value of the paper mark was stabilised at a rate of 4,200 billion marks for a gold mark. And one Rentenmark became equivalent to one gold mark.

The new Rentenmark wasn’t convertible into gold. But just the simple fact that the new money had a different name from the old instilled confidence. As Bresciani-Turroni explained:

“Of the simple fact that the new paper money had a different name from the old, the public thought it was something different from the paper mark... the new money was accepted, despite the fact that it was an unconvertible paper currency.”

And so, when people stopped hoarding foreign currency, the velocity of circulation of paper marks declined. And the increased willingness to hold domestic currency reduced the inflation problem in and of itself. The Rentenmark ended up circulating together with the paper mark for almost a year.

The passing from hyperinflation to complete stability was sudden. The budget was re-established and expenses cut so that equilibrium was reached. The introduction of new taxes and reduced pressure in terms of reparation payments also helped. In 1924-25, the government finally achieved significant budget surpluses.

Counter-intuitively, a shortage of money emerged despite trillion dollar bills. The reason was that domestic prices had increased so much, and the depreciation was so severe that there was not enough money to satisfy the volume of transactions at current prices.

This shortage was best measured through the concept of “real money supply” (=money supply deflated by inflation), which started shrinking from late 1923 onwards. The circulation of money in mid-1922 was 15-20 times the pre-war days, while prices had risen 40-50 times.

The shortage of money in real terms led to the following outcomes

Trade was arrested as companies could not gain access to working capital. Factories closed, and unemployment rose.

Interest rates increased, and heavily indebted individuals went bankrupt. At the end of 1923, the “call money” interest rate reached 30% per day.

The real money supply shrunk so much that eventually, the entire money supply amounted to only 444 million gold marks, compared to a Reichsbank gold reserve of 1 billion gold marks. That enabled the Reichsbank on 30 August 1924, to fix the conversion rate of the new Reichsmark at a rate of 1 trillion paper marks per US Dollar. In other words, since the value of the money supply had dropped below the Reichsbank’s holdings of gold, it was easy to peg the currency to gold yet again.

After the new Rentenmark and Reichsmark were introduced, prices stopped rising, and the paper mark strengthened against gold. Factories re-opened, unemployment declined, and confidence revived.

Production moved from fixed assets as iron & steel moved to consumption goods.

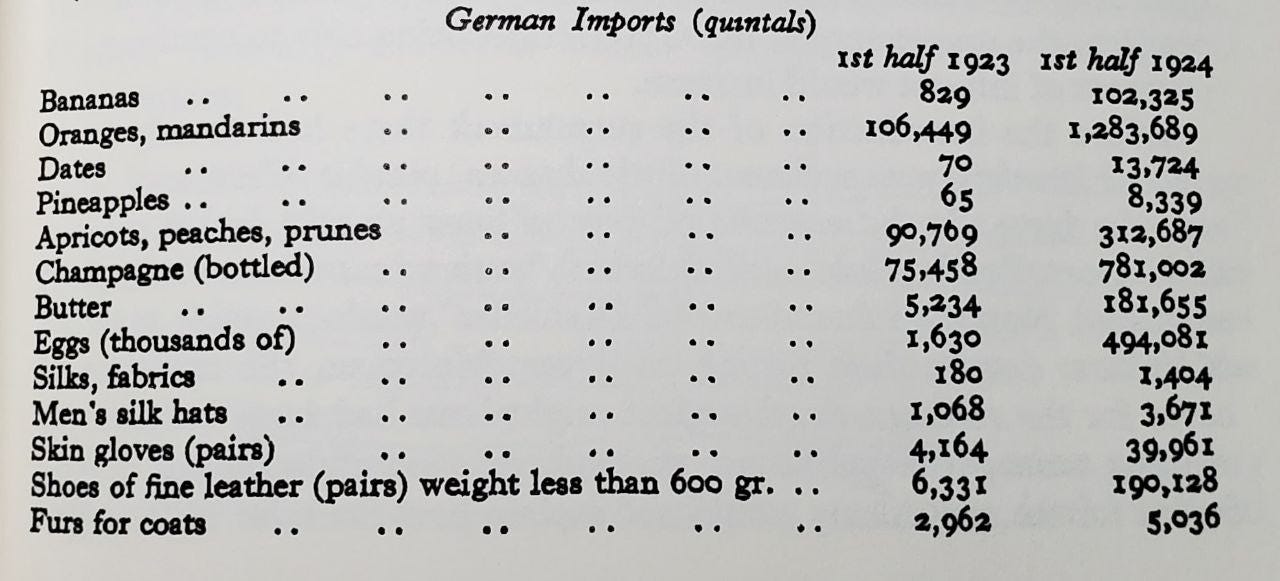

And there was an increase in consumption across broad parts of society, especially among salary and wage-earners. Imports increased considerably, especially for luxury goods. There was a rise in home demand for textiles. The agriculture and building industries saw a renaissance. And in the first few months of 1924, there was a craze for foreign travel, something the German public had been deprived of for years. The consumption of meat rose from 22kg in 1923 to 41kg in 1924, also suggesting a significant improvement in living standards.

Meanwhile, Germans stopped buying real assets to protect their capital. Production of fixed assets dropped. Seventeen cement factories shut down. 118 potash mines were closed or abandoned. 75% of shipyard capacity was deemed useless after the building boom of 1920-23.

While the financiers had benefitted from the hyperinflation, from late 1923 onwards, “finance” became the most difficult business of all. Once the currency stopped depreciating, the demand for foreign exchange declined significantly. The productivity of industrial enterprises improved. Companies were spun off, and groups became more decentralised, more specialised.

Previous conspicuous consumption of furs, perfumes, fine soaps, high-class cigars, flowers, carpets, jewels and precious metal goods disappeared. The sale of rare books also declined. The little luxury theatres, expensive cabarets and cafes that sprung up in Berlin during the inflation closed one after another. Instead, huge popular restaurants, vast cinemas, public baths and stadiums catering to the broader population were built to cater to the rising middle class.

While during the inflation, the Reichsbank had become the sole source of credit, new commercial banks regained their old role of financing small and medium enterprises across the country.

2. Lessons from the book

2.1. Inflation was caused by monetised budget deficits, assisted by a corrupt central bank

There was a theory at the time that a weak balance of payments caused Germany’s hyperinflation. That speculators would buy foreign currency continuously, causing the mark to depreciate.

But obviously, their savings would sooner or later deplete. The only way that the mark could continue to be sold is if new money was created. And the government has only itself to blame.

While the reparation payments can’t have helped, they were certainly not the most important cause of the budget deficit. Whether the socialist government had the political support to implement tax reforms is unclear.

What we do know is that as soon as Germany got its budget deficits under control in 1924, the mark stopped depreciating. The price level stabilised.

I was surprised to read that the Reichsbank directly lent money to speculators to buy foreign currency. The fact that borrowing quotas were used suggests foul play. Only a specific group of individuals were given access to their under-priced loans.

It’s also worth mentioning that wealthy industrialists such as Hugo Stinnes publicly opposed any tax reforms, presumably since that would lead to an end of inflation. Adversaries of proposed higher tax rates were so strong that they managed to wreck any project in the Reichstag that aim to achieve greater tax revenues.

2.2. The way to make money was to borrow and invest in foreign currency or real assets

While the vast majority of Germans entered poverty as their savings depleted and their wages drop in real terms, there were also huge private fortunes made from 1919 to 1924.

While the fortunes created before the war were typically related to some invention or efficient production of goods, the winners of the inflation were the speculators and the gamblers:

Some were dealers of foreign exchange or stocks

Some made money out of the import-export trade

Others used depreciating bank borrowing to buy real assets such as metals

The common denominator is that they used cheap borrowing to either buy real assets or foreign currency.

Buying property in Germany did not protect your purchasing power since rents did not keep up with inflation. Buying a small farm was a better alternative. Or some type of fixed assets that would prove to be in demand even after the inflation period, such as gold or silver.

2.3. Avoid fixed income securities like the plague

The securities that did the worst during the inflation were banks and insurance companies since their assets were more or less fixed income in nature. Banks were also forced to keep fast-depreciating paper money available to depositors.

Conversely, the mines and metal industries were able to increase prices in line with inflation, and they managed to preserve their book value in gold terms from the pre-war levels to 1925.

Stocks that had extensive foreign interests (“valutapapiere”) were more sensitive to monetary depreciation, and they acted as better inflation hedges better than the overall German stock market.

So the lesson here would have been to avoid any type of fixed income security, even infrastructure assets that were partly inflation-protected through, say, fare adjustments. When inflation really picks up, such adjustments rarely protect you fully.

2.4. Hyper-inflations create epic lows for equities

During the post-war period, speculators shifted their attention between foreign currency and the stock market back-and-forth.

In 1920-21, shares were seen as the best way to protect your capital against the ravages of inflation. Then from mid-2021 onwards, there was a rush into foreign currency and a panic out of shares, causing an epic low in the index by October 1922, when Bresciani-Turroni’s index of 300 stocks had dropped over 97% from the pre-war highs.

Marc Faber has previously called this phenomenon “The Paradox of Inflation”. While hyperinflation causes an incredible rise in domestic price levels, currencies often drop even faster than inflation, causing bargains in the stock market. German shares have never been cheaper than they were close to the height of the hyperinflation in 1922. Though at that time, few people were brave enough to buy.

The seasoned speculator would have shifted between foreign currency and German stocks whenever either asset became less popular and more attractive in terms of valuation. And go all-in on the stock market when the hyperinflation reached its crescendo.

3. Concluding remarks

I felt a bit sickened reading the book. Unnecessary suffering for reasons that are hard to grasp. Society is clearly better off when the individuals that produce something of value are rewarded, rather than those that speculate using borrowed money.

The problem in Weimar Germany seems to have been related to the Reichsbank’s lack of independence. But even worse, the Reichsbank got involved in direct lending, favouring certain individuals over others, and that lending was even used to dump the currency in what looked like a circular loop.

As investors, all we can do is adapt. And the way to do that is to be wary of large, persistent budget deficits and excess money creation. It probably makes sense to be wary of countries with twin deficits (budget + current account deficits) as their currencies are at risk of continuous money printing and related selling pressure.

And when a country reaches peak hyperinflation, consider buying shares in that country. In Germany’s case, that was when the stock market had fallen 97% in US Dollar terms. Buying during crises is a high-risk endeavour, but high-risk sometimes also provides a high reward.

Great post Michael!

I didn't realize they where doing selective lending.

One conclusion we had reach in analyzing the various hyperinflation scenarios is that you need a large imbalance between local and global economy.

People keep saying USD is strong right now, it's more like jpy and EUR (which account for large % of dxy) are weak.

It seems common for governments to do special/subsidized lending programs. Europe's green bonds. The US did subsidized rates for war vets to purchase homes and farmers to pay for land.

Will be interesting to see what's in store next as rates rise.