The Japanese restaurants that will prosper beyond COVID

Fast-food and sushi are taking market share on a secular basis, but the izakayas have the greatest recovery potential. Estimated reading time: 36 minutes

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Table of contents

1. A short history of Japanese food

2. Restaurant industry sector trends

2.1. Low-priced restaurants taking market share

2.2. Consolidation

2.3. Franchising

2.4. Central food kitchens

2.5. Automation

2.6. Overseas growth

2.7. Delivery services

2.8. COVID-19

2.9. Rising prices

3. Investable universe of stocks

3.1. Fast-food restaurants

3.2. Sushi restaurants

3.3. Family restaurants

3.4. Japanese BBQ

3.5. Chinese restaurants

3.6. Pubs & Izakayas

3.7. Coffee shops

4. Hidden champions of Japan F&B retail

4.1. Arclands Service

4.2. Gift Holdings

4.3. Genki Sushi

4.4. Torikizoki

4.5. Yossix

4.6. WDI (World Dining Inspirations)

5. Conclusion

Summary

The Japanese restaurant market is essentially a no-growth industry

The only ways to achieve growth are by having exposure to segments such as fast-food or conveyor-belt sushi, by expanding overseas or by taking market share within a segment

I’ve identified a few companies that I believe are offering something unique. Izakaya pub operator Yossix is run like a tight ship and is differentiated through its focus on rural areas. Arclands has developed machinery in-house that enables its popular pork katsu restaurants to be run by non-professionals. Gift Holdings’ Machida Shoten ramen broth is winning customers’ hearts, and the runway of potential growth seems large. Customers like the uniformly low prices offered by the leading izakaya chain Torikizoku. The Western-style restaurants run by WDI Corp enjoy exceptionally positive reviews. And finally, Genki Sushi’s Shinkansen food delivery trains are a hit with families with young children.

The restaurant categories that were hurt most by COVID-19 were the pubs and izakayas and the casual- and fine dining segments. These are now on a clear recovery path.

In my view, the izakaya pubs Yossix and Torikizoku both have recovery potential from COVID-19. Genki Sushi’s overseas restaurants were also hurt by pandemic lockdowns and should perform better going forward.

Introduction

The restaurant industry is competitive. The barriers to entry are minimal, and successful concepts can easily be copied.

So success in the food & beverage retailing industry is often about execution. Having a laser-focused CEO work towards a specific vision: developing the right recipes, choosing the right locations, hiring the right people, and pleasing a specific customer demographic.

Given the lack of “moats” in the sector, I’ll investigate which of the restaurant chains in Japan are truly doing something different and ground-breaking. I’ll investigate which Japanese restaurants might do well beyond COVID-19.

1. A short history of Japanese food

Japanese people have historically eaten mostly plant-based food, focusing on rice, vegetables and seafood.

A typical meal would be rice served with side dishes such as vegetables, miso soup and grilled fish. Soy products such as tofu and soy sauce have also been staples of the Japanese diet for over a thousand years.

During China’s Tang Dynasty, around 618-907 AD, Chinese-style wheat noodles (“ramen”) were introduced to Japan. Ramen noodles are made of wheat flour and eaten in a rich soup broth. And since then, new types of noodles dishes have developed in Japan. Eating buckwheat noodles (“soba”) became popular in mountainous regions and wheat noodles (“udon”) in coastal regions. Chinese-style dumplings (“gyoza”) has also become a staple food at many Japanese restaurants.

The invention of sushi initially came from southern China. Packing raw fish in vinegared rice was originally a way to preserve it. Today, of course, refrigeration solves that problem. And the spread of refrigerators in the past century has made sushi more popular. Technically, the word “sushi” refers to the rice, which is prepared together with vinegar, sugar, salt and other seasonings. The raw fish is either consumed on its own (“sashimi”), on top of a small piece of vinegared rice (“nigiri”), through maki rolls or on top of a bowl of rice (“chirashi”).

After the Meiji restoration in 1868, foreign cuisine started exerting greater influence on Japan’s restaurant industry. In the late 19th century, the curry was served at Japanese hotels catering to foreigners. Curry rice became a popular dish among locals, though milder and sweeter than its Indian counterpart. French cuisine inspired the Japanese to create rice with omelette and ketchup (“omurice”), which has become a staple among Japanese children. Deep-fried dishes such as pork in breadcrumbs (“tonkatsu”) were also invented during this period. Other types of Western-style dishes introduced since the Meiji restoration include steaks, hamburgers, bread, pastries, sandwiches and coffee.

Following World War 2, Japanese-style pubs (“izakayas”) became popular as Japan urbanised and the nightlife blossomed. Izakayas serve alcohol together with side dishes such as grilled chicken skewers (“yakitori”), fried octopus balls (“takoyaki”), steamed soybeans (“edamame”), etc.

Japan’s fast-food industry took off through the popularisation of McDonald’s in the 1970s. Soon thereafter, local competitors such as Mos Burger and Korea’s Lotteria started popping up, and hamburgers have become a staple of the Japanese diet. KFC has also become popular, notably during the Christmas season, which many Japanese celebrate by eating buckets of KFC chicken. Local fast-food options such as beef bowls (“gyudon”) and takeaway bento boxes have also become popular.

2. Restaurant industry sector trends

Japan’s restaurant industry is essentially a no-growth industry, where overall sales barely keep up with inflation. The culprits are weak demographics and competition from convenience- and grocery stores.

But underneath this stability, you’ll find that the sector is at the intersection of a number of trends that are affecting each restaurant differently. I’ll now go through some of these trends one by one.

2.1. Low-priced restaurants taking market share

Like in most other countries, fast-food restaurants are taking share from mid-priced competitors. In Japan, that sector is dominated by McDonald’s, but also local family restaurants such as Saizeriya and cheaper izakaya pubs such as Torikizoku.

Western cuisine is also becoming more popular, a trend that’s probably benefitting the major fast-food restaurant chains such as KFC Japan and McDonald’s Japan.

Customers that go to fast-food outlets do so for a quick, affordable meal. In contrast, the appeal of casual dining or fine dining restaurants is often to try something new. But that also means that they are constantly forced to seek new customers, which makes it difficult for such restaurants to remain successful year in, and year out. Fast-food restaurants don’t have that problem.

2.2. Consolidation

Several of the large Japanese restaurant group are engaging in M&A to roll up the industry, with varying degrees of success.

Japan’s restaurant industry continues to be made up of many small and mid-sized operators that generally have low margins and low efficiency. As their founders become older, they often sell their restaurants to larger companies that want to take advantage of the loyal customer bases of each restaurant.

Examples are Colowide’s hostile takeover of Ootoya in 2020, Yoshinoya’s acquisition of ramen noodle franchise Link Holdings, and Create Restaurants’ acquisition of noodle restaurant operator Kiya Foods.

The most acquisitive restaurant conglomerates include Skylark, Zensho, Create Restaurants and Colowide. As is typically the case for acquisitive companies, the return on equity for those companies remains relatively low, suggesting that the strategy isn’t working very well.

2.3. Franchising

An asset-light way to grow is through a franchisor model, whereby franchisees pay for their own capex and operations while the franchisor receives royalties for providing expertise, brand name and the operating model. The franchisee model is especially popular in the fast-food segment.

Many franchisee operations are also forced to buy ingredients from captive suppliers, further taking away from the economics of running a restaurant. Some franchisee restaurants are running at very low margins.

The difficulty of investing in a listed franchisor is that we often don’t know the unit economics of the franchisees. That’s especially true when the royalty fees are not directly proportional to sales. In Komeda’s Coffee’s case, for example, the franchisor receives an up-front payment that boosts short-term revenue but presumably at the expense of future earnings.

In my view, the franchisee model works best when the brand name is strong, and the restaurant is a “destination” of sorts. If a company is relying on strong foot traffic for the locations chosen, there’s no point paying extra royalties to a franchisor.

2.4. Central food kitchens

Food processing plants tend to be automated to a much greater extent than restaurants themselves, enabling a low marginal cost of production and economies of scale for the supply chain as a whole. A centrally located food processing plant can supply many restaurants within, say, a specific city.

After food is delivered to a restaurant, it is then heated and served to customers. The restaurant is thus able to save labour costs and doesn’t need to hire chefs and specialist staff. As Kenkyo Investing has argued in the past, an entire restaurant could, in theory, be run by “a high schooler with a microwave”.

Food delivered from a central food kitchen is unlikely to be as flavourful or with as good a texture, but technology is improving. Most customers won’t be able to tell the difference.

It’s also worth mentioning that the central food kitchen model doesn’t work as well for restaurants serving fresh food, including sushi restaurants. From what I can tell, the model using central food processing plants is used particularly for fast-food outlets such as Yoshinoya and family restaurants such as Saizeriya and Gusto.

Companies that benefit from this trend are the incumbents with large, underutilised central food processing plants. As well as refrigerator equipment manufacturers such as Nakano Refrigerators and freezer storage companies Nichirei and Yokorei.

2.5. Automation

COVID-19 pushed restaurants to introduce automation into their operations earlier than they otherwise would have. So far, robots are mostly used to guide customers to their tables, take orders, deliver the food and, in special cases, also prepare it.

Automation through robots is used to greet guests and, in some cases, even take orders. In most cases, robots are used today to take guests to their tables and/or deliver food to them. The major suppliers of such robots include SoftBank Robotics and Omron. Such robots have been introduced to Skylark’s Syabuyo shabu-shabu restaurants, Monogatari’s Japanese barbecue restaurants and Watami’s izakayas, to name just a few.

Ordering is increasingly done via tablets with specialised software developed by start-ups such as TouchTo, Huber, Qmenu and Smary. Other restaurants, such as McDonald’s Japan use self-ordering kiosks and allow customers to pick up their food at a centralised location. Some restaurants, such as Zensho’s Sukiya, use QR codes on tablets that customers scan with their smartphones. Customers then pay online via their smartphones.

Food preparation is also increasingly becoming automated, at least to some extent. For example, sushi robots have become popularised by Suzumo Machinery, which invented them in the 1970s. The company still has an 80% market share in sushi rolling machinery. You can find Shared Research’s excellent initiation report on Suzumo Machinery here.

In other areas, Fuji Seiki produces rice ball machines that help produce onigiri. Shibuya produces bottling systems. Kitazawa Sangyo sells frying machines to restaurants. And Rheon Automatic Machinery produces encrusting machines and bread makers.

That said, it’s proven hard to completely automate the cooking process. Placing seafood on rice is difficult for machines to do. Robots cannot slice meat or vegetables or place finished the food on plates. So, for now, machines are mostly used for rolling or packaging sushi or for frying or heating up food.

2.6. Overseas growth

Since Japan’s restaurant industry is stagnant, many brands are pushing for overseas expansion to drive growth. As a spokesperson for the ramen chain Chikaranomoto said:

"Overseas there is significant demand for ramen restaurants, and there is room for the market to grow… We are opening shops faster than in Japan."

Kura Sushi, for example, is targeting overseas locations to make up 40% of all shops by the end of this decade. Genki Sushi is also targeting growth in Southeast Asia. Pub operator Watami has said publicly that it wants to increase its footprint in China.

2.7. Delivery services

Japan’s delivery industry is dominated by Uber Eat and local competitor Demae-Can, which is backed by SoftBank and Naver via its parent Z Holdings. Demae-Can began by offering delivery of restaurant food but has since then expanded to offering grocery delivery as well. Restaurants with in-house delivery capabilities can use Demae-Can’s platforms to collect orders and pay a small commission for the trouble. Restaurants without delivery capabilities can use Demae-Can’s delivery options as well. Most of Demae-Can’s drivers are working for third parties, though some remain in-house. You can read fellow Substacker Will Schoeb’s excellent introduction to Demae-Can here.

Other delivery service competitors include Foodpanda, and NTT Docomo’s Yume Navi, which delivers meals from convenience stores such as 7-Eleven and Lawson.

Since delivery is expensive, I would imagine that delivery services can only capture a small part of the market. For a single customer, going to a local ramen shop will still be far cheaper. And delivery services cannot replicate the experience of taking your date to a high-end restaurant, for example.

2.8. COVID-19

The overall Japanese restaurant industry saw its sales drop about 15% in 2020, the steepest fall since statistics started to be collected in the early 1990s. The hardest hit sub-segments were the pubs and izakayas, followed by casual dining and fine dining restaurants. Coffee shops around office areas or railway stations were also hurt by the pandemic.

Some of the measures that restaurants had to undertake were to space out tables, reduce seating capacity and install plastic screens to avoid air circulation. In some areas, restaurants were prohibited from serving alcohol for a specific period of time. And certain bars had to stop operating as early as 8 pm, making their opening hours restricted. Contact tracing efforts were introduced. All of these measures impacted the restaurant industry, especially for those restaurants serving alcohol.

Restaurant operators shifted their focus to solo customers and in many cases, had to reject groups of three or more. The average size of a restaurant-booking party fell from 5-6 before the pandemic to 3 in the middle of it, according to Gurunavi’s restaurant guide.

At the other end of the spectrum, some pizza joints and fast-food outlets maintained or even increased their sales during the pandemic, partly by relying on demand via delivery services. Restaurants offering drive-through ordering, including KFC, did well. Uber Eats and Demae-can were the primary beneficiaries. Even high-end restaurants were forced to shift their focus to take-away demand, offering boxed lunches for takeaway and home delivery.

This newfound popularity of delivery services also led to a short boom in cloud kitchens that only prepare food and do not serve it. One such example is Ghost Restaurant Laboratory in Tokyo, which restaurant chain Toridoll invested in.

Now that COVID restrictions are easing, many restaurants are shifting back their expansion to urban locations such as train stations, offices and tourist attractions. It remains to be seen how fast customer behaviour will revert back to what it used to be before COVID-19.

2.9. Rising prices

The rapid depreciation of the Japanese yen in 2022 drove up the costs for food service companies. Labour shortages during the pandemic also caused wages to rise. Restaurant profit margins therefore suffered.

Many restaurants are now raising prices, though reluctantly. Here is a summary of the price increases we saw in 2022:

It’s also clear that consumers are becoming more thrifty. That trend may well benefit low-cost operators such as fast-food chains.

3. Investable universe of stocks

I think the best way to make sense of the Japanese industry is to divide them into the following seven categories:

Each of these categories of restaurants has different growth and profitability characteristics. I’ll now go through them one by one.

3.1. Fast-food restaurants

Japan’s fast-food restaurants offer affordable food in restaurants with simple decorations. Customer turnover is typically fast. The food is mostly produced in central food kitchens and then reheated on the spot. And fast-food outlets typically expand through the use of franchisees, which take on most of the capital expenditure and pay the brand owner royalties.

Among Japan’s hamburger restaurants, McDonald’s Japan reigns supreme. McDonald’s entered the Japanese market in 1971 through the help of entrepreneur Den Fujita. That story was told well by the YouTube channel Allocators Asia here. What Den Fujita did was to adapt McDonald’s menu to Japanese tastes, with the introduction of the Teriyaki burger, Ebi Filet-O shrimp burger and McPork sandwich, to name just a few. It’s a franchisee of McDonald’s Corporation and pays royalty fees for the privilege of using the brand, menu, and so on, as well as the ingredients. Local hamburger chain MOS Burger is another strong competitor, which came up with innovations such as the rice burger.

The fried meat category is dominated by KFC Japan, which has been around for over 50 years. It’s become a tradition in Japan to eat KFC for Christmas. This is due to its 1974 “Kentucky for Christmas” campaign, which argued that fried chicken was a suitable alternative to then-hard-to-find Christmas turkey. This KFC Christmas meal is sold in the form of party barrels with fried chicken, sides and a cake. Technically, KFC Japan is a franchisee of Yum Brands, but it also has franchisees of its own.

Another type of fast food is Japanese rice bowls (“gyudon”). It’s a sub-sector that isn’t growing particularly fast. It’s dominated by three restaurant chains:

Yoshinoya has been around for 120 years and remains a household brand with over 1,000 restaurants both in Japan and overseas.

Zensho’s chain of Sukiya rice bowl restaurants. Zensho also owns a large number of other restaurant chains, including the Big Boy hamburger restaurant, family restaurant Coco’s, Seto Udon, shabu-habu restaurant Hanaya Yohei and more.

Matsuya is the third-largest beef bowl chain, with about 1,000 restaurants. It also runs a pork cutlet chain called Matsunoya and a sushi restaurant chain called Sushimatsu.

I’m also a big fan of curry rice specialist CoCo Ichibanya. Its flavourful curry is served with deep-fried pork cutlet. The price point is a bit higher than typical gyudon or Western fast food restaurants. Another pork tonkatsu restaurant is Arcland Service’s Katsuya chain. This chain does not serve curry but rather deep-fried pork on top of rice, also known as “katsudon”.

Within the self-service udon noodles category, Toridoll operates the chain Marugame Seimen. The company also runs the yakitori family dining restaurant Toridoll and pork cutlet restaurant Butaya Tonichi. The Japanese udon restaurant market grew fast prior to COVID-19 and probably has some growth potential.

Reviewing Google Trends, it looks to me like McDonald’s, KFC and Zensho’s Sukiya are doing well, most likely thanks to their low prices.

In terms of operating margins, McDonald’s Japan remains the clear outperformer, save for a period around 2015 when customers avoided McDonald’s after an incident with expired chicken making customers sick. KFC also enjoyed decent margins during the pandemic. And the third outperformer is the curry rice restaurant Ichibanya, as mentioned above.

Same-store sales trends during COVID were the strongest at McDonald’s, perhaps thanks to its delivery services. Yoshinoya and Ichibanya performed poorly, while Zensho was somewhere in between. I believe that these same-store sales trends will mostly reverse as consumption patterns normalise now that pandemic restrictions have mostly been eased.

Neither of the Japanese fast-food operators looks particularly cheap, except potentially KFC Holdings Japan at 12.1x EV/EBIT. But I believe that KFC benefitted from COVID-19 thanks to its drive-through options and takeaway menus. Arcland Service, which runs the highly popular katsudon chain Katsuya trades at only 12.1x EV/EBIT - a low multiple compared to the competition.

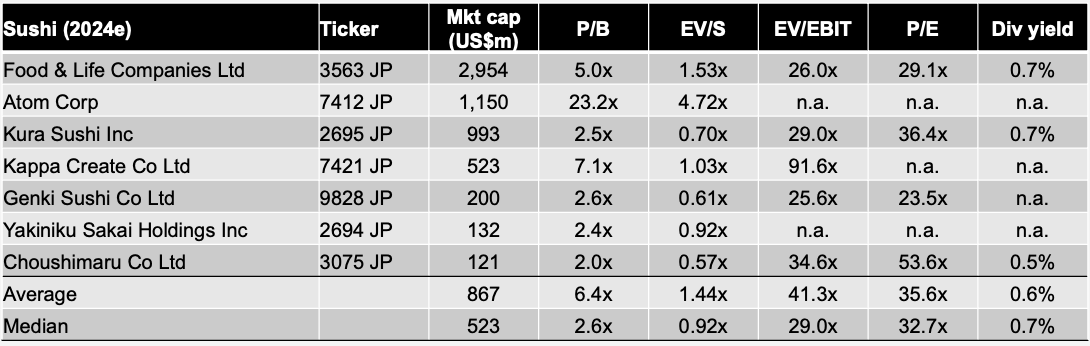

3.2. Sushi restaurants

In the past, sushi restaurants have traditionally been high-end service operations, where customers sit at a counter in front of a chef. That chef would then serve raw fish on vinegared rice, a service that’s labour-intensive and also expensive in terms of ingredients.

But since the 1950s, lower-priced conveyor belt sushi chains (“kaiten-zushi”) have become popular. In such restaurants, small sushi dishes are transported through conveyor belts. Customers then choose the dishes they like.

More recently, kaiten-zushi restaurants have introduced tablets used for ordering, while the conveyor continues to be used to deliver the items to each table. Many brands also use automated sushi-making machines.

Japan’s kaiten-zushi market has been growing on a secular basis, except for a slight decline during the depths of COVID-19. Some argue that the sushi restaurant market has been in a bubble, although from what I can tell, most operators are still showing decent numbers.

You can tell from the below same-store sales numbers that Japan’s sushi chains weathered the pandemic relatively well thanks to takeaway and delivery services. Some restaurants even installed lockers for their takeaway food, which customers can easily access through a code delivered to their smartphones.

The sushi restaurant industry is dominated by four separate chains: Sushiro, Kura Sushi, Hama Sushi (owned by restaurant Zensho) and Kappa Sushi (owned by Kappa Create):

Industry leader Food & Life Companies runs the now-famous conveyor-belt sushi restaurant Sushiro, which operates mostly in suburban locations. It also owns Japanese sushi pub Sugidama, and the Kyotaru sushi take-out service.

Kura Sushi has a large footprint of sushi restaurants Japan. It also has an overseas operation, partly through its separately listed Taiwanese subsidiary Kura Sushi Asia and through its US subsidiary Kura Sushi USA.

Kappa-Create owns Kappa Sushi, another conveyor-belt sushi chain. It also owns a company manufacturing bread and sushi for convenience stores.

Genki Sushi is known for its Shinkansen train system of delivery and operates overseas via the help of franchisee Maxim’s Group.

Reviewing Google search query data, it looks like consumer interest in Food & Life Companies’ Akindo Sushiro, and Kura Sushi is increasing. Genki Sushi is doing well, too, especially overseas.

Margins have been the highest for Food & Life Companies. And indeed, Sushiro seems to be an outperformer, perhaps thanks to its low prices and high-quality ingredients.

Looking at the trading multiples, Genki Sushi is priced at a reasonable multiple vs its pre-pandemic operating profits, especially given its success overseas. Few Japanese restaurants have done well overseas, whereas Genki’s brand name and product offering seem distinctive enough to make a mark, at least in Southeast Asia. You could argue that Kura Sushi trades at a low price compared to its US and Taiwanese subsidiaries, but note that the company has a significant amount of debt.

3.3. Family restaurants

The family restaurant segment emerged in the 1970s, targeting families looking for affordable, child-friendly food in suburban locations. They typically have diverse menus with a standard, affordable fare.

Since the food in family restaurants is typically simple, it can be produced at a central food manufacturing plant and then reheated at each location, helping bring down costs and prices. But if you go to a family-style restaurant, don’t expect haute cuisine.

Examples of family restaurants include Skylark with its restaurant chain Gusto, ramen restaurant Ringer Hut, Gusto, Royal Host and Italian restaurant Saizeriya.

Skylark runs the popular family-oriented restaurants Gusto and Jonathan’s, focusing on Japanese and Western-style basic dishes such as hamburg steaks, curry rice and pasta.

Saizeriya is a restaurant chain focusing on extremely low-priced Italian fare such pasta, pizza, risotto and more.

Create Restaurants has strength in all-you-can-eat buffet restaurants and food courts, but has grown significantly through M&A. Its most popular restaurant is Japanese-style pub Isomaru Suisan.

Colowide is the parent of Skylark, and also owns izakaya chain Tsubohachi and popular yakiniku chain Gyu-Kaku.

Royal Host is a family restaurant serving Western food such as hamburgers, pasta, curry and more.

The same-store sales trends in the family segments were weak in COVID-19, and I would imagine that some of them will have recovery potential in 2023.

Judging from Google search queries, consumer interest in Saizeriya is going up, while it’s more stagnant for Skylark restaurants Gusto and Jonathan’s, Royal Host and Create Restaurant’s Isomaru Suisan.

Margins have been weak almost across the board, suggesting little benefits from centralised food processing plants. My guess is that these restaurants are now facing tough competition from fast-food outlets and, therefore unable to charge high prices.

While Saizeriya’s margins aren’t necessarily market-leading, the stock seems reasonably inexpensive at just 0.7x EV/Sales. That said, Saizeriya’s return on capital has been horrendous at just 6%.

3.4. Japanese BBQ

Japanese BBQ restaurants serve grilled skewers of yakiniku (grilled beef) or yakitori (grilled chicken), or where customers cook food on their own tables, sometimes with the help of restaurant staff.

Japanese hotpot (“shabu-shabu”) is also part of this segment. Shabu-shabu is a casual dining option whereby customers boil meat and vegetables in water with seasonings.

Monogatari’s Yakiniku King is a suburban Japanese barbecue chain, but the company also runs several other shabu-shabu, sushi and other restaurant concepts. Anrakutei focuses on the yakiniku-focused family restaurant with the same name, also operating at roadside locations with a low price point. Amiyaki Tei is another yakiniku and yakitori restaurant operator using domestic and wagyu beef only, though at higher prices.

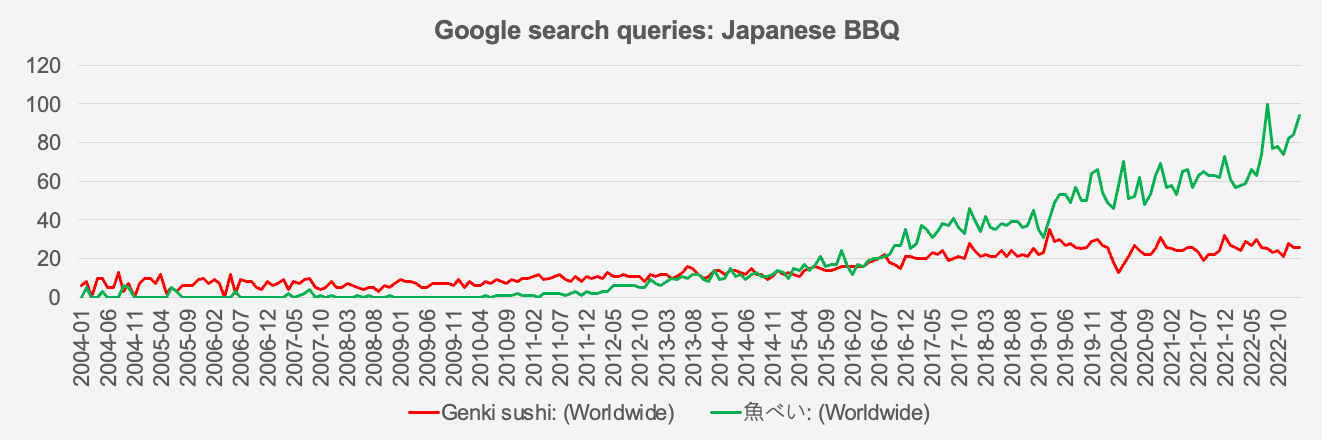

Google search query data suggests that Yakiniku King is growing well. Monogatari’s average Google review score of 3.8 is also significantly higher than Anrakutei’s 3.4 and Amiyaki Tei’s 3.6.

Monogatari’s margins have been lower than those of its peers but has earned a high return on capital of almost 20% prior to COVID-19. Amiyaki Tei’s margins have also been decent.

Monogatari trades at an EV/EBIT of 12x and a forward P/E of 18x, which may qualify it as a GARP-type stock. But I believe it was a COVID-19 beneficiary, so I would not extrapolate the success it’s had during COVID-19.

3.5. Chinese restaurants

Japan’s Chinese restaurants serve gyoza, ramen, fried rice, spring rolls, etc but with a Japanese twist. They tend to be less spicy, less oily and less salty than their counterparts in China.

The main companies in the Chinese restaurant industry in Japan include:

Kansai-based Ohsho Food Service’s restaurant chain Gyoza Ohsho. The company runs a tight ship with a franchisee operation run primarily by former employees of the company. The organisation is decentralised, with each restaurant having the ability to design its own menus. Extensive take-out options may have helped it during COVID-19.

Hiday Hidaka’s Hidakaya serves low-priced ramen, gyoza and other Chinese dishes in their 440 restaurants around Tokyo. Most outlets are near train statations, and therefore highly dependent on railway station foot traffic. The company is known to be shareholder-friendly.

Ringer Hut runs the noodle restaurant Ringer Hut and the tonkatsu restaurant Hamakatsu.

Meanwhile, Kourakuen is more of a pure-play ramen establishment.

Same-store sales have been weak during COVID-19, especially for Hiday Hidaka’s restaurant chain Hidakaya which is reliant on the sales of alcohol.

You can see that search query growth has been decent for most Chinese restaurants in Japan, but especially for Ohsho’s restaurant Gyoza no Ohsho. It’s a growth market.

Hidakaya’s prices are low, yet the chain has managed to achieve high margins throughout most of its history thanks to the sale of alcohol in its outlets. An exception is during COVID-19, when sales went down the drain, just like for most izakayas. Ohsho Food Service has also enjoy consistently high operating margins.

Neither of Japan’s Chinese restaurants trades at particularly low multiples, in my view. I’m impressed with Gift Holdings, though, and I will speak more about it later.

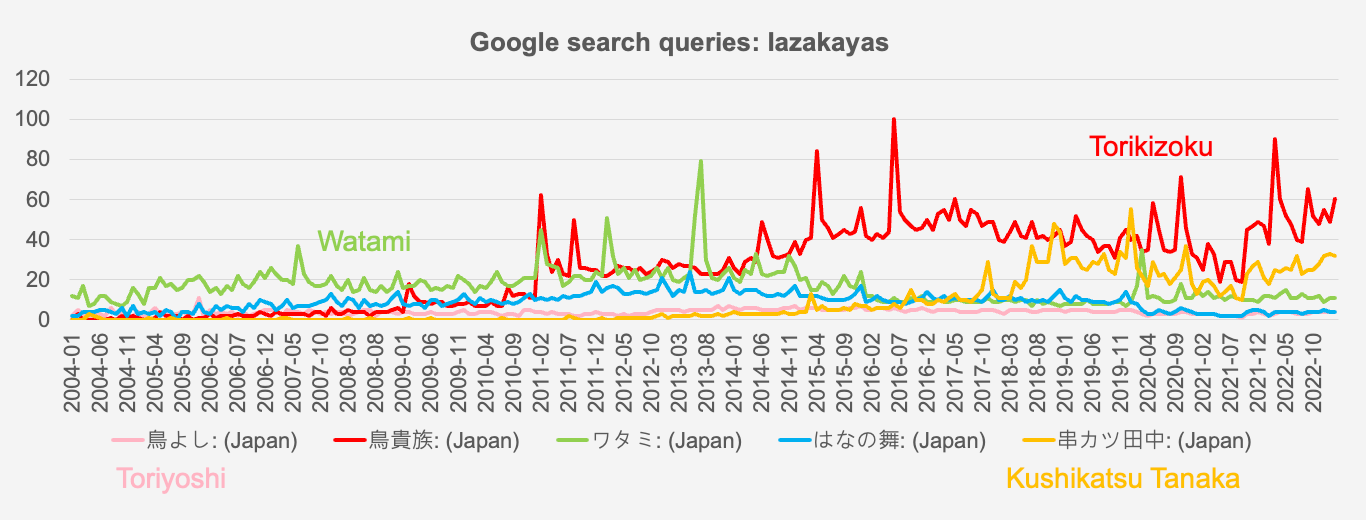

3.6. Pubs & Izakayas

Most Japanese listed pub operators focus on izakaya establishments, which can be seen as Japanese versions of tapas bars. Izakaya literally means a place where you stay and drink, as opposed to taking the alcohol home.

Customers typically order drinks, together with a variety of snacks such as grilled skewers, sashimi, and deep-fried dishes. This food is typically served in small portions and is meant to be shared among the group.

Competition within the izakaya industry is said to be fierce, and it’s also a category that’s been especially hit by COVID-19 as people have avoided social interactions.

One of the more popular izakaya chains is Torikizoku, famous for its chicken and 300 yen-across-the-board prices. Another large family-run chain is Watami, whose different brands serve a variety of dishes, including fusion-inspired options. Chimney operates in the mid-priced segment under the ownership of a liquor firm that sells its product via the restaurant. Kushikatsu Tanaka specialises in deep-fried skewers and is popular among young people.

I see momentum in the following two izakaya chains: Torikizoku and Kushikatsu Tanaka. Torikizoku suffered after its price hikes in 2017, but it has adjusted its operating model and is now growing again.

The pre-COVID operating margins were the strongest at rural izakaya chain operator Yossix and Western-style pub operator Hub Co.

Several of the izakayas and pubs trade well below 1.0x revenues. With pre-pandemic margins of Yossix and Hub Co at 10% and 7% respectively, you could well argue that they’ll trade close to or even below 10x normalised EV/EBIT. Both of them have earned a decent return on equity. Torikizoku also appeals to me as a consumer, given its low price point. I’d imagine that the company will be able to grow for many years.

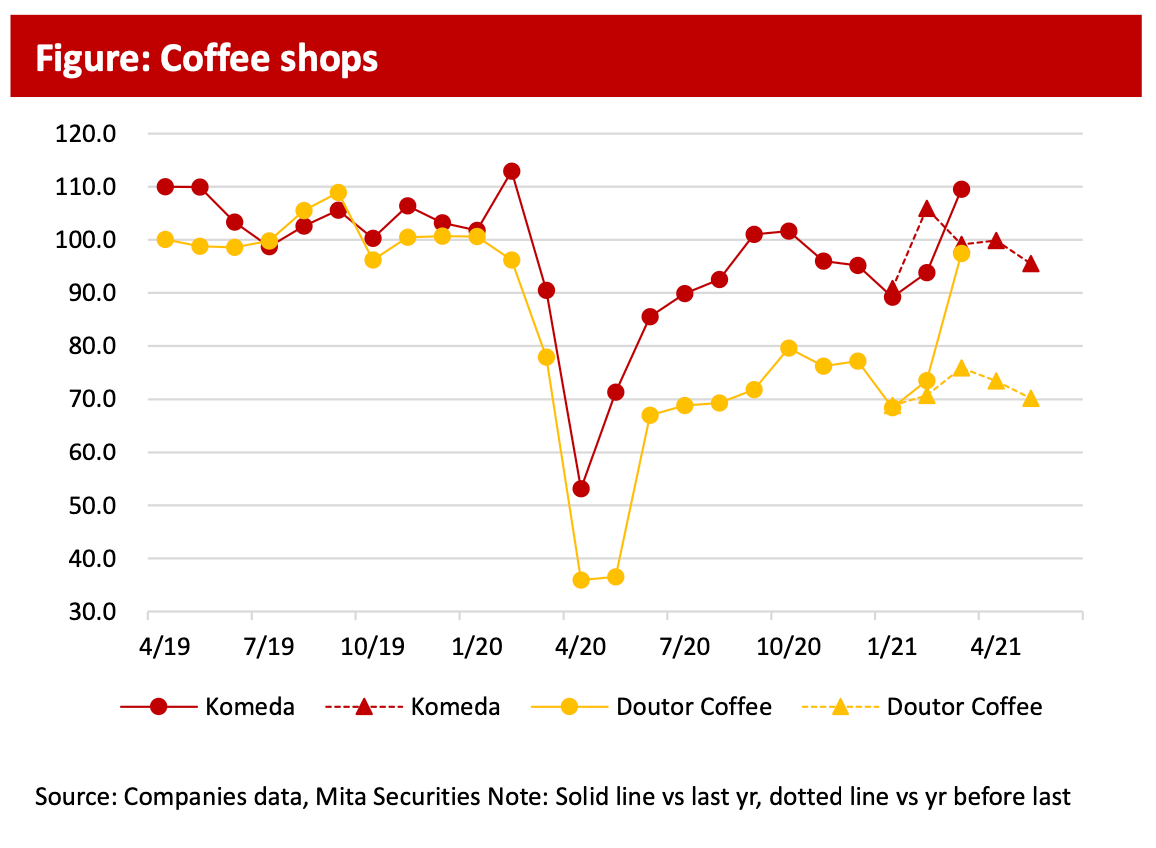

3.7. Coffee shops

Dutch traders brought coffee to Japan towards the later part of the 18th century. Consumption has increased since “manga shops” started popping up in Japan in the 1970s, serving coffee and free comic books for reading. Then came Internet cafes, Starbucks, vending machine coffee in and finally, fresh coffee served by local convenience stores.

Japan’s coffee shops are typically situated in areas with high foot traffic, such as in central areas or next to railway stations. But there are also suburban alternatives, where customers come by car and tend to stay for longer.

While coffee consumption has gone up, the number of coffee chains has declined considerably as independent cafes have shut down and the likes of Starbucks have taken market share.

US-based Starbucks served the higher end of the market, while local coffee chain Doutor serves what you might consider the working-class demographic. Parent Doutor Nichires also owns Excelsior Caffe, which focuses on sit-down coffee shops with more traditional decor. Komeda’s Coffee have a greater focus on suburban locations, with much lower customer turnover. Meanwhile, Saint Marc is a mid-priced coffee chain focusing on bread items such as its “chococro“ pastry.

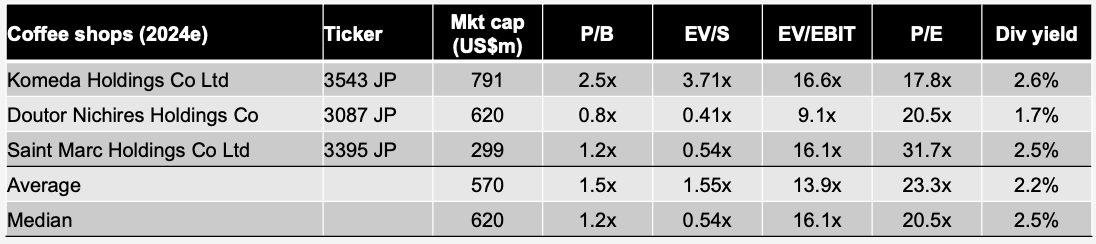

The following chart shows you that Starbucks and Komeda have taken market share in recent years from independent coffee shops and, to a lesser extent, Doutor and Saint Marc.

The Japan Customer Satisfaction Index has put Starbucks and private equity-owned Caffe Veloce at the top, followed by Doutor.

Google search query data suggest a rapidly growing consumer interest in Komeda’s coffee, with stagnation evident for both Starbucks and Doutor.

In terms of operating margins, Komeda’s are far above those of the competition. But note that Komeda is reliant on fees paid by its franchisees, which are predominantly fixed and front-loaded. I wonder whether their franchisees are particularly profitable.

Doutor Nichires continues to trade at a low EV/Sales multiple, while its revenues are likely to recover with greater railway commuter volumes. Note that Doutor’s pre-pandemic ROE was weak at just 6%.

4. Hidden champions of Japan F&B retail

When it comes to finding the so-called “hidden champions” of Japan’s food & beverage retailing industry, I veer towards low-cost companies.

Additionally, since pubs and izakayas performed poorly during COVID-19, I imagine that some of them will see recovery in their earnings in 2023 and 2024.

I pay particular attention to the pre-COVID return on equity and also the incremental return on equity as a company grows. For restaurants, you’ll want a return on equity to remain high, flat and consistent as they continue to grow.

With that in mind, here are six Japanese restaurant operators that I think are exceptional in one way or another.

4.1. Arclands Service

Arclands Service (3085 JP - US$514 million) operates Katsuya, a restaurant chain focusing on tonkatsu, i.e. deep-fried pork cutlets. The company is a subsidiary of home centre operator Arclands focused on the Niigata prefecture.

Katsuya is famous for its low-priced menus compared with most other tonkatsu restaurants, with a bowl costing as little as JPY 490 each. The company ensures high-quality standards through automatic deep fryers, which were developed in-house together with a key supplier.

The number of Google search queries has gone up in quite a consistent fashion over time.

Reviews from Google mention how the food is surprisingly good, with affordable prices and generous portions, despite a 3.5 ranking. Comments include:

“This place is incredible for what you pay. A fast food restaurant like this is proof that Japan does not play around when it comes to food quality”

“Such a cheap place with amazing fresh testing katsu, the soup is also insaaannneee”

“I am not sure as to why this shop has 3.5 review when I saw it. They deserve more. Perfect service and food... very easy to order.”

“Pretty solid tonkatsu and katsudon for cheap and fast! Perfect for when you’re on the go or for a quick bite. Like it better then your traditional beef bowl spots!”

Today, the stock trades at 19.9x 2024e consensus P/E, with a clean balance sheet. While the margins are impressive at 14%, the return on equity has only been in the mid-teens, perhaps due to large investments in machinery.

4.2. Gift Holdings

Gift Holdings (9279 JP - US$289 million) runs a ramen chain called Machida Shoten (町田商店). It’s based in Yokohama and runs directly-owned stores in the Western part of Greater Tokyo.

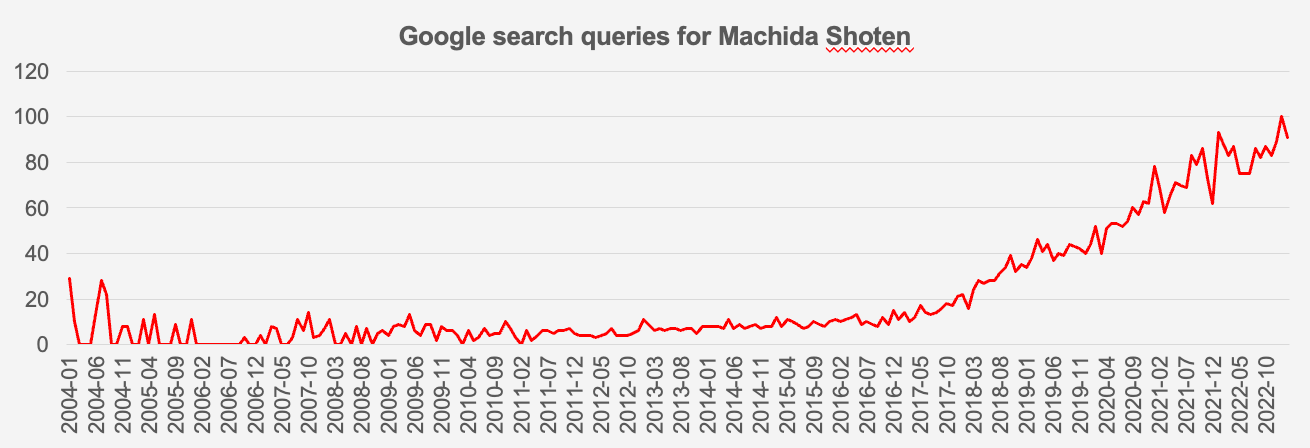

Revenue growth has been solid and consistent at over 20% per year, and the Google Trends chart supports that Machida Shoten is increasing its footprint over time. Growth is funded by internally generated capital with a return on equity of about 30%, while margins are high at around 11%. Since Machida Shoten is only present in western Tokyo, I believe that the potential runway of growth remains large.

Machida Shoten serves up Yokohama-lekei ramen noodles, which uses a pork-bone-based soup with soy sauce and medium-thick noodles. The noodles are manufactured in-house, while the soup comes from third parties. The key selling point of the Machida Shoten seems to be the soup broth.

The Google Review score is average at around 3.6. A few notable comments:

“The ramen itself was really great. The place is a little cramped and crowded but that's normal fare for a ramen shop in Machida.”

“One of the best ramen i ever ate but the place is a bit smelly”

“Delicious ramen, lively staff, cheap prices - get over there! Dine alone or with friends.”

“Visited for the third time. This is the perfect restaurant for those who like rich miso ramen.”

The company is run by a 41-year-old man called Sho Tagawa, who opened Machida Shoten in 2008. You can find an interview with him here (Japanese language), where he clearly displays a love for ramen and the industry.

Today, Gift Holdings trades at a consensus 2024e P/E of 23.8x, which is fairly low for a company with a large runway of growth and an ROE of almost 30%. That said, the stock price has almost doubled in a year, which may scare off some investors.

4.3. Genki Sushi

I first wrote about Genki Sushi (9828 JP - US$200 million) back in early 2021:

At that time, I made the point that Genki Sushi’s overseas franchisee stores in Singapore and Hong Kong were performing exceptionally well and that the concept could probably be replicated across Southeast Asia and the rest of the globe. I also made the case that Genki’s restaurants would eventually recover from COVID-19.

What makes Genki Sushi unique is its playful assortment of sushi, as well as its “Shinkansen” delivery trains that serve the food to customers. I think Genki Sushi’s offering is differentiated and especially suitable for families with young children.

In Japan, most outlets carry the Uobei brand name, while Genki Sushi-branded sushi restaurants are predominantly small-sized neighbourhood restaurants.

Global Google search queries for Genki Sushi have been flat since COVID-19, but those for Uobei are showing a nice upward trend.

The median Genki Sushi Google review score is 3.8, a fairly high number. A few comments, just to illustrate the customer experience:

“Affordable and delicious foods!”

“What was strange about Uobei's menu. What is tanuki udon (without fried egg)?”

“There were a lot of unusual sushi, and it was very delicious and I'm glad ☺️”

“Easy to find along the national highway, cheap and delicious.”

“Cheap and yummy! Food is served very fast (using Shinkansen trains)! Strongly recommended! Just that crowded during weekend dinner time”

“Instead of sushi flowing in the lane, if you order on your tablet, a large plate in the shape of a bullet train or vehicle will be brought to you in the lane. Your child will enjoy it.”

Today, Genki Sushi trades at 12.8x pre-pandemic P/E. The company’s profitability has been uneven, with a median return on equity of 14%, though masking significant volatility. A question mark is Genki’s relationship with parent Shinmei, a producer of rice, which also acts as a related party supplier to Genki Sushi itself.

4.4. Torikizoki

Torikizoku (3193 JP - US$172 million) is a low-price Izakaya chain that’s become wildly popular among young working-age professionals. It’s known for its 320 yen prices across its entire menu. People come here after work to socialise, drink beer and have drink chicken skewers.

Here is an introduction to the chain. Ordering takes place through tablets but gets delivered by staff. The menus are limited, ensuring low inventory and higher efficiency.

Google reviews are above average with a median score of 3.7. A few comments include:

“If you want fast and affordable food this is the place to go. You can order via a tablet at the table which also has English options. Once ordered, everything arrives quickly and is pretty tasty for what it is.”

“Value for money and the yakitori is good! Everything is priced at 298 yen (b4 tax) so it means the alcohol here is nicely priced!”

“If you are looking for a cheap but good place to dink it's the right place for you. But be aware that it is full most of the time so you should make an reservation in advance.”

The chain expanded fast in the early 2010s and then raised prices in 2017. Customers responded by going elsewhere, and to deal with the problem, Torikizoku closed unprofitable stores with greater margin control through a new decentralised “amoeba management” system. It now operates its own food processing plant manufacturing its proprietary yakitori sauce.

The company is run by Tadashi Ohkura. Not much is known about him, but he used to write a blog on the Ameba platform where he pronounced that he wants Torikizoku to become the best yakitori restaurant in the world. He is 62, and his son is not involved in the business.

Torikizoku has recovered nicely from the COVID-19 pandemic, earning JPY 1.2 billion in net profit in FY2022. That puts the stock on a P/E ratio of about 20x. The most recent return on equity print was about 20%.

4.5. Yossix

Yossix (3221 JP - US$161 million) runs Japanese-style pub chains, with all outlets directly owned. While each concept is different, with an okonomiyaki and grill concept called Yataiya, sushi pubs Yatai-zushi and Nipachi, a common denominator is that they all offer uniformly priced dishes with alcohol.

The company’s strategy is also unique in the way that it focuses on rural areas, where the workforce can be easily secured and where its small- and midsized pubs of 99-132 square metres can be opened at low costs.

A review of a Yatai-zushi outlet can be found here. The largest concept Yatai-zushi has a Google review score of 3.9, which is high in a Japanese context. A few comments include:

“Really cheap food and very tasty, we were so surprised the bill was so cheap for 3 people when we saw it.”

“It was cheap, delicious and good!”

“All-you-can-eat and all-you-can-drink for 3,000 yen for 2 hours is highly satisfying.”

“I thought that 8000 yen was a good deal for a family of 4 with a 100 yen drink campaign.”

The company is run by Masanari Yoshioka who remains Chairman and President and exerts significant control over the operations (the name Yossix is inspired by his surname). He started out in the construction business and then opened a franchisee store for a bento box chain before finally striking out on his own. Every single store is directly owned under the control of Yoshioka, which in my eyes, minimises risk for minority investors who typically don’t have full insight into the profitability of franchisees.

Like most other izakayas and pubs, Yossix has been hurt badly by the pandemic, but with an improvement in the most recent quarter. The stock trades at 2024e P/E of 17.1x but only 13.8x pre-pandemic, full-recovery earnings. A normalised return on equity is expected to reach around 20%, in my view.

4.6. WDI (World Dining Inspirations)

WDI Corp (3068 JP - US$105 million) - also known as “World Dining Inspirations” - operates Western-style restaurants with both proprietary brands and as a franchisee for overseas brands.

The proprietary brands include Italian restaurant Capricciosa, New York-style breakfast restaurant Sarabeth’s, Hawaiian cafe Eggs ’n Things. The overseas brands include Wolfgang’s Steakhouse, Hard Rock Cafe and Tony Roma’s. It also has the franchise rights to operate Michelin-star restaurant Tim Ho Wan in the US and Europe.

WDI seems to partly target inbound tourists to Japan, which makes me think it will do well now that the borders are opening up. WDI has also started to expand to US territories such as Hawaii and Guam.

WDI’s restaurants have Google review scores across the board: 4.2 for Hard Rock Cafe, 4.0 for Tony Roma’s, and 3.8 for proprietary brand Capricciosa - all above the median level of 3.6. To take Capricciosa as an example, Pizzas cost about 2,000 yen and pasta is closer to 1,200 yen, making it a mid-priced option. Tony Roma’s and Hard Rock Cafe are significantly more expensive. Examples of a few reviews I found on Google:

“The Garlic Tomato Spaghetti here is the best on the entire planet. This is one of the best affordable Italian restaurants in the world IMO.”

“Very nice food, the tomato spaghetti was great as usual. Had a bit of trouble actually finding the place because it kinda blends into the background, but the food was worth it!”

“Had an absolutely fantastic dinner here tonight! Service and food were both exceptional.”

“Always a lot of fun, with lots of unique memorabilia to see. The food is amazingly consistent, regardless of where in the world you are. The service is excellent and prices are reasonable.”

The company is run by the Shimizu family. Chairman Yoji Shimizu started the original Playboy Club in Tokyo’s Roppongi district and has strong connections with Wolfgang Puck and others. He is now 82 years old. His son Ken Shimizu runs the day-to-day business and seems energetic. Ken has a law degree from Keio University and previously worked for a bank and 25 years at WDI in sales and business development. He has been the company’s president since 2003.

Apart from a weak period in the early 2010s, WDI Corp has earned a return on equity of about 20%. That may be attributable to the fact that WDI serves Western food, which might offer something unique compared to what the average Japanese eats at home, perhaps providing the company with some pricing power.

Given that WDI is a franchisee operator, it only earned about 5% operating margins prior to COVID. Assuming full recovery from COVID-19, I could imagine an operating income of JPY 1.5 billion, which would put the stock on an EV/EBIT of 11x. That’s low for a company with such a high return on equity and seemingly decent execution.

5. Conclusion

While the Japanese restaurant market is a no-growth industry, I personally think there are companies with growth potential. Examples include Arclands’ Katsuya chain of katsudon restaurants, Gift Holding’s ramen restaurants and Genki Sushi’s sushi restaurants with their Shinkansen train ordering and delivery system.

I also believe certain restaurant operators will see a strong recovery from COVID-19, particularly the izakayas. Torikizoku is the market leader, but I also believe that Yossix will do well after the pandemic.

If you would like to support me and get 20x high-quality deep-dives per year and other thematic reports like this, try out the Asian Century Stocks subscription service - all for the price of a few weekly cappuccinos.

Michael, you might have a look at Infomart (2492 jp). They supply software, mainly to the restaurant business in Japan. Stock has sold off because of an acquisition I think. But one of the activist investment funds owns 8% of the company now.