Table of Contents

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

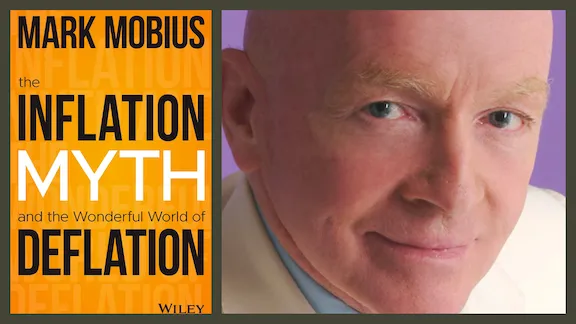

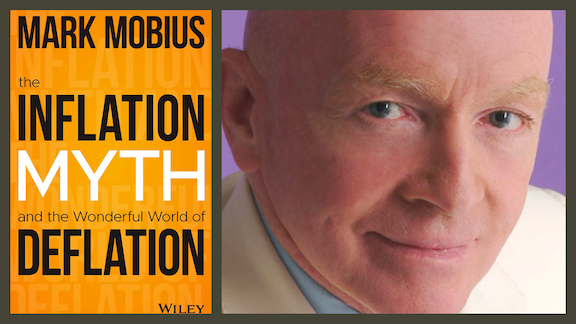

Mark Mobius is not a fan of inflation.

In his new book The Inflation Myth, emerging market fund manager Mark Mobius tells you all you need to know about inflation. How central banks were created to enable governments to spend money they didn’t have. How excess spending explains much of the inflation pressures we’re seeing today. And how government inflation statistics almost always understate the true nature of inflation.

If true inflation is higher than we think, it will have widespread ramifications for asset prices. Regulated assets whose revenues are adjusted in line with CPI may not offer as much inflation protection as you think.

1. A brief history of inflation

Inflation can be defined as a loss of purchasing power - your $100 being able to buy fewer and fewer goods and services over time.

The first known example of widespread inflation was in the fourth century BC when the ruler of Syracuse “Dionysius” had the brilliant idea of dealing with rising debts by changing the face of all coins. Each coin became worth two, thus halving the debt burden at a stroke.

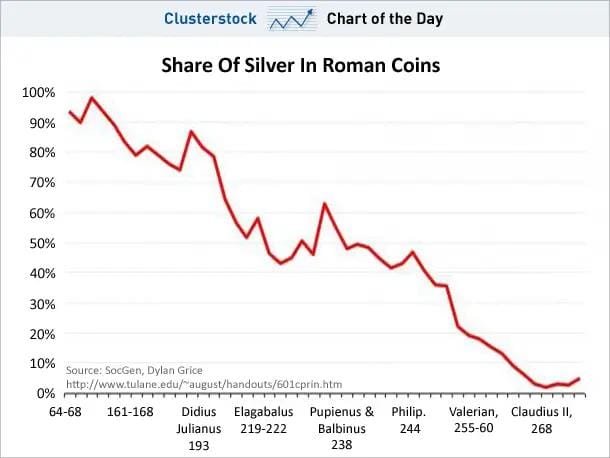

Similar debasement took place in the Roman Empire, with the silver content falling from 100% to less than 10% in the span of 200 years:

The invention of paper money in seventh-century China accelerated the process towards inflation. But throughout most of subsequent history, such paper money was usually backed by gold or silver as coins had been in the past.

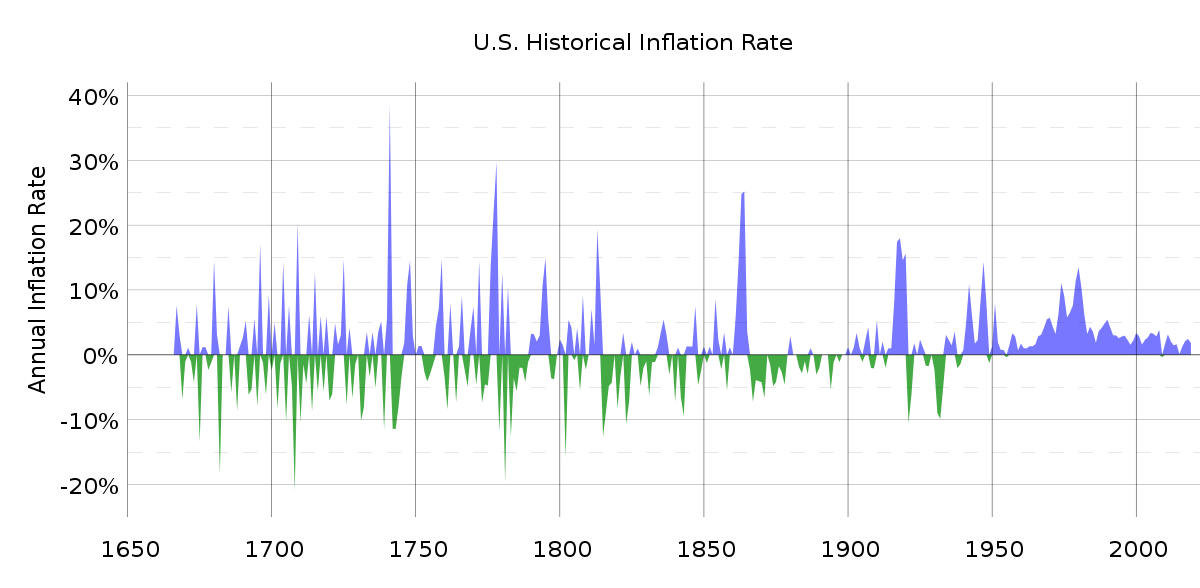

In the 17th to 19th century United States, when the US Dollar was mostly backed by hard currency, periods of inflation and deflation mostly balanced each other out. So net-net, inflation pressures remained modest.

The US economy was strong during this period. For example, between 1870 and 1900, the US experienced a multi-year period of deflation. The mechanisation of labour, improved transport infrastructure, oil lamps and so on caused productivity improvements that led to lower prices. Such deflation was not harmful at all - quite the opposite:

“Thanks to the spread of electricity and other such wonders in the final quarter of the 19th century, prices dwindled year by year at a rate of 1.5% to 2% per year. People didn't call it deflation – they called it progress.” - Jim Grant

As you can tell from the chart above, the US inflation rate has picked up significantly since the early parts of the 20th century. Mobius argues that central were created by governments to spend money they didn’t have. For example, both world wars were financed through large budget deficits in the United States and Europe. And the US inflation rate only picked up after President Nixon severed the link between gold and the US Dollar back in 1971.

Since then, we’ve been in a pure fiat world. The US Dollar is not backed by anything except the fact that domestic contracts need to be denominated in US Dollars (“legal tender laws”) and that you need US Dollars to pay your taxes.

So it’s difficult to speak of any “intrinsic value” of our fiat currencies, per se. The supply and the demand for them are usually stable until savers become concerned about government spending. But until this point, the path of least resistance for most individuals is to keep their savings in the national currency.

Meanwhile, governments have their own constraints. If they’re not careful, a big loss of purchasing power can cause voter discontent. Understanding this risk, governments generally try to keep inflation in the low single digits - high enough to favour itself and vested interests but not high enough to cause voters to revolt.

Today, most democracies have ended up with inflation targets of around 2%, including the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve, though the latter has a dual mandate of low inflation and maximum employment.

2. Inflation comes from excess money creation

According to Mobius, there are four theories of where inflation comes from:

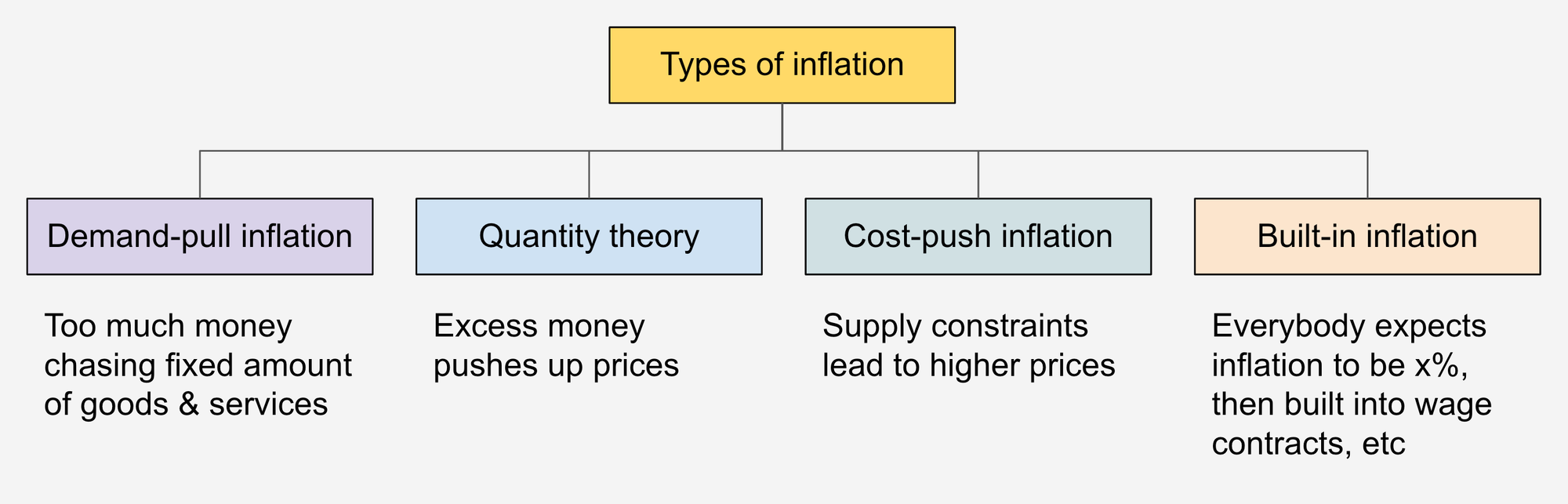

- Economist John Maynard Keynes argued that inflation comes from too much demand chasing a limited number of goods and services. This is also known as demand-pull inflation.

- Another economist, Milton Friedman, argued that it’s usually excess money that causes demand to increase in the first place, causing inflation to shoot up. This explanation is known as the quantity theory of money.

- The third theory of inflation is cost-push inflation, when supply constraints lead to higher prices. However, those tend to be temporary.

- Finally, when everybody expects inflation to be x% every year, they will demand their wages to keep up with inflation. Companies will also be pushed to raise prices by an equal percentage to keep their profit margins intact. This is what’s known as built-in inflation.

In my view, demand-pull inflation seems to be the explanation for long-term inflation pressures. But the primary cause of this higher demand growth is clearly excess money creation. People need higher salaries to spend more, and salaries don’t shoot up for no reason.

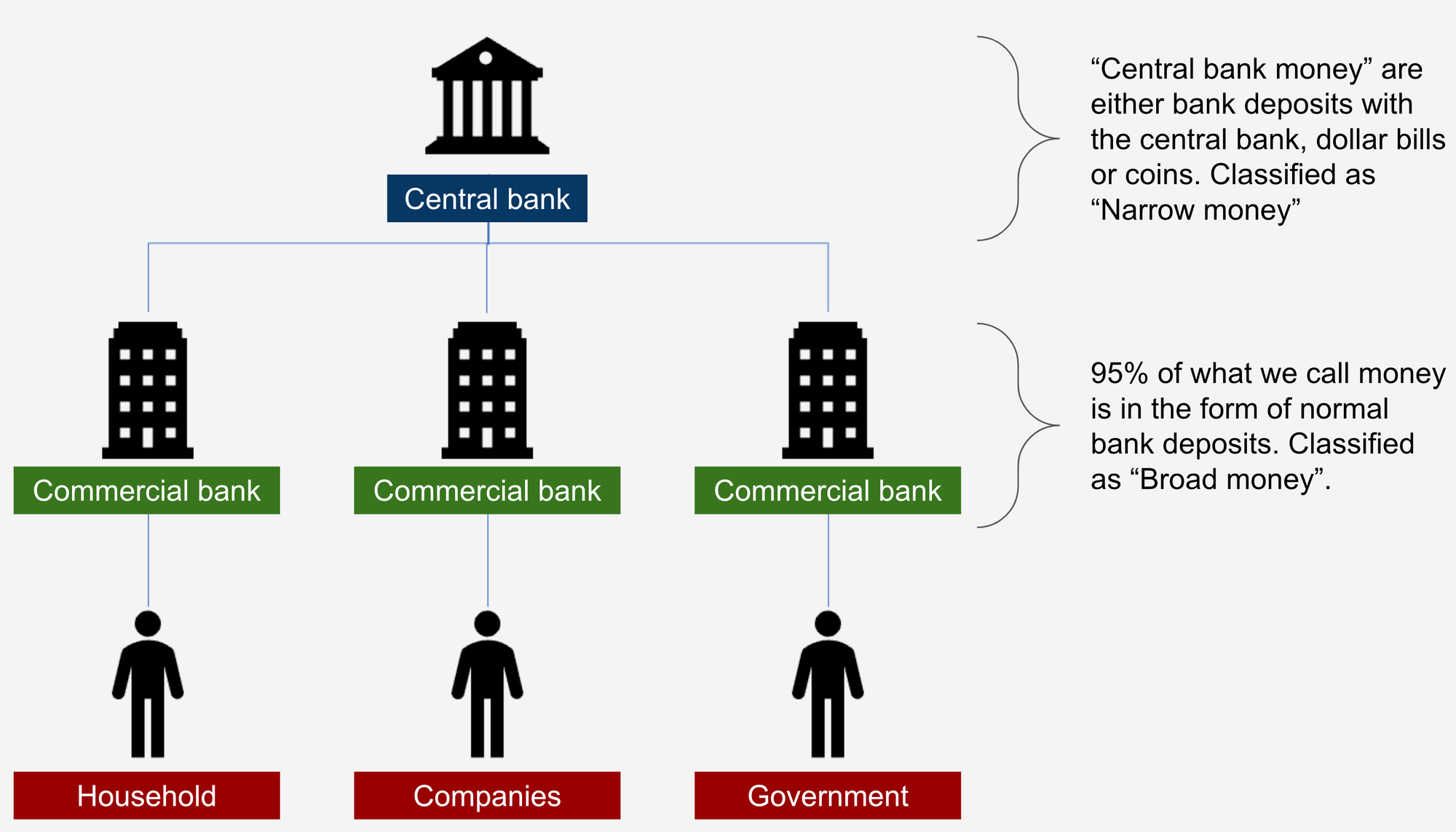

The process by which money is created in today’s fractional reserve banking system is complex. Households, companies and the government put their money in normal commercial banks. Commercial banks then set aside a percentage of those deposits in the central bank to ensure they have enough liquidity for potential withdrawals.

When most people think of money creation, they often picture central banks printing new money, either physical bills or adding reserves that commercial banks hold with the central, in a process called quantitative easing.

But the type of money we call central bank reserves are “stuck” in the banking system and cannot be spent on goods and services. And so they don’t really affect consumer price inflation. Today, when the link between commercial bank lending and the quantity of central bank reserves has been severed through the introduction of interest on excess reserves, they’re only used to settle liabilities between banks. The quantity of reserves doesn’t matter much for inflation anymore. Central bank money is also known as “narrow money” and is only 5% of the total money in circulation.

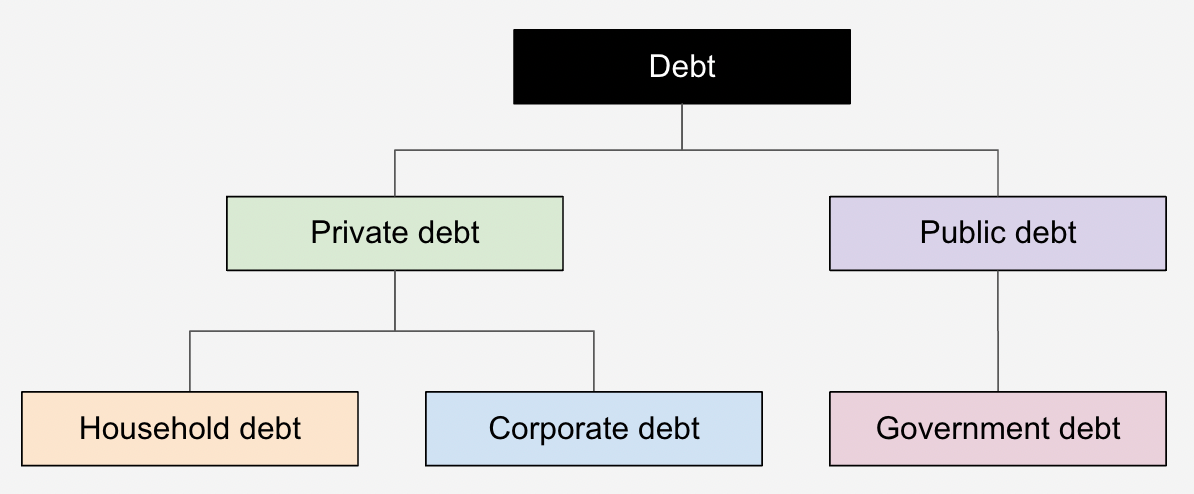

The remaining 95% of the money comes in the form of normal commercial bank deposits. And those bank deposits don’t grow by “money printing”. Instead, commercial bank deposits grow whenever someone takes on a new loan: either private sector borrowers such as households or corporates or the public sector through central and local governments:

It almost seems like magic. But in a fractional reserve banking system, bank loans can be created out of thin air, increasing the money supply. For example, if you take on a mortgage to buy a property, you receive money from the bank, and the seller of the property receives money in a bank deposit. The total amount of bank deposits in the economy suddenly increased.

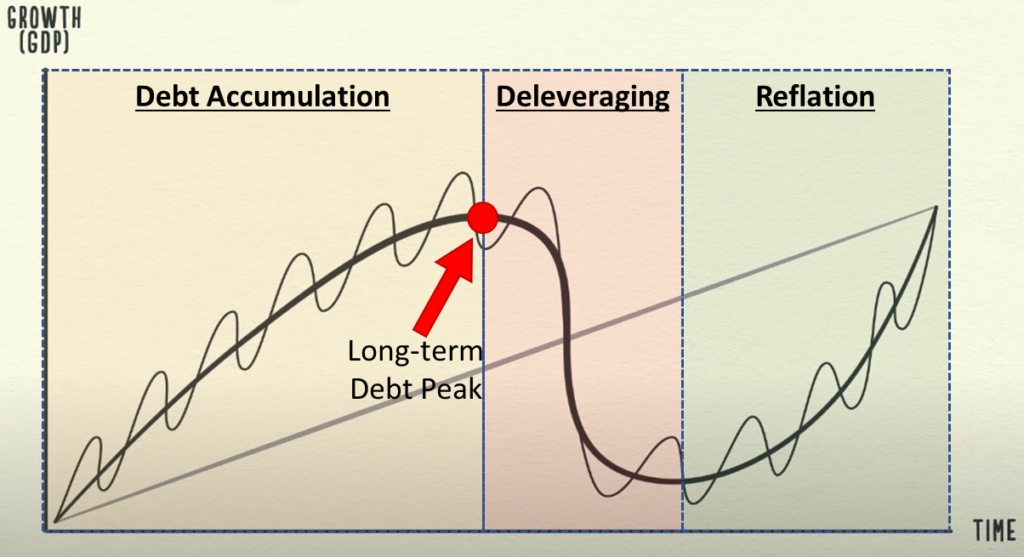

Private sector money creation typically moves in long-term cycles. When there is not much debt in the economy, any new loans will have a large impact on the money supply and therefore push inflation higher. Eventually, the private sector becomes so indebted that it cannot take on any more debt - despite zero interest rates. The economy reaches the end of the debt accumulation phase.

At this point, governments can step in and ramp up their budget deficits. If they do it well, they’ll help deleverage the economy. If they don’t do it well, governments end up over-indebted. So at the end of the long-term debt cycle, they need to be careful in how they act:

- In a Great Depression scenario, government budget deficits are too-low or completely absent while the private sector reduces its debt. This causes a large contraction in the money supply. Widespread bankruptcies ensue.

- In the Japan scenario, new government borrowing just-about balance private sector deleveraging and nominal growth remains almost the same as the interest rate. You end up with a functioning economy but no money supply growth. Debt/GDP remains the same. Low-interest rates also enable zombie companies to survive, causing productivity to suffer.

- In a “beautiful deleveraging” scenario, the government budget deficit is large enough for growth to reach “escape velocity” - with nominal income growth greatly exceeding the interest rate. This happened during the Second World War when “yield curve control” kept interest rates low while high budget deficits allowed the economy to deleverage. And eventually, a new long-term debt cycle began twenty years later.

So borrowing creates new money, which then chases a limited amount of goods and services, driving up prices in the process. This debt accumulation continues until the private sector has so much debt that it’s reluctant to take on any more debt. It’s then up to the government to step in if it wants inflation to continue.

3. Interest rates determine the cycle

It’s not inevitable that the private sector gears up to unsustainable levels as I described above. The driver of higher leverage is typically that interest rates are so low that you’d be a fool not to borrow. And when interest rates are too low, those who have the ability to borrow benefit at the expense of all others in the economy.

In 1932, American economist Irving Fisher came up with the concept of the real interest rate. It can be described formally as:

Real interest rate = nominal interest rate - expected inflation rateFisher argued that the nominal interest rate matters less than the interest rate adjusted for inflation. For example:

- A 4% interest rate in a 6% inflation environment, with a real interest rate of -2%, should be seen as attractive

- Whereas a 2% interest rate in a zero-inflation environment, a real interest rate of 2% should not

The problem with Fisher’s view is that it doesn’t predict actual borrower behaviour. Few borrowers take on debt hoping that consumer prices will fall so that they can buy consumer goods later for a cheaper price. That’s just not how borrowers think.

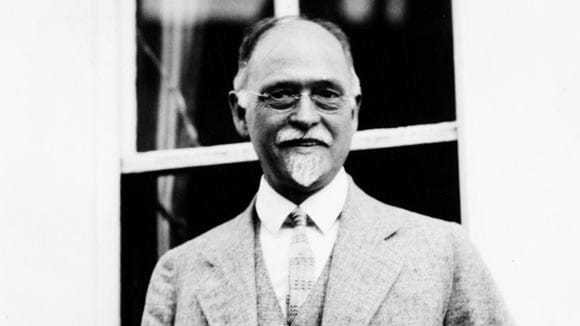

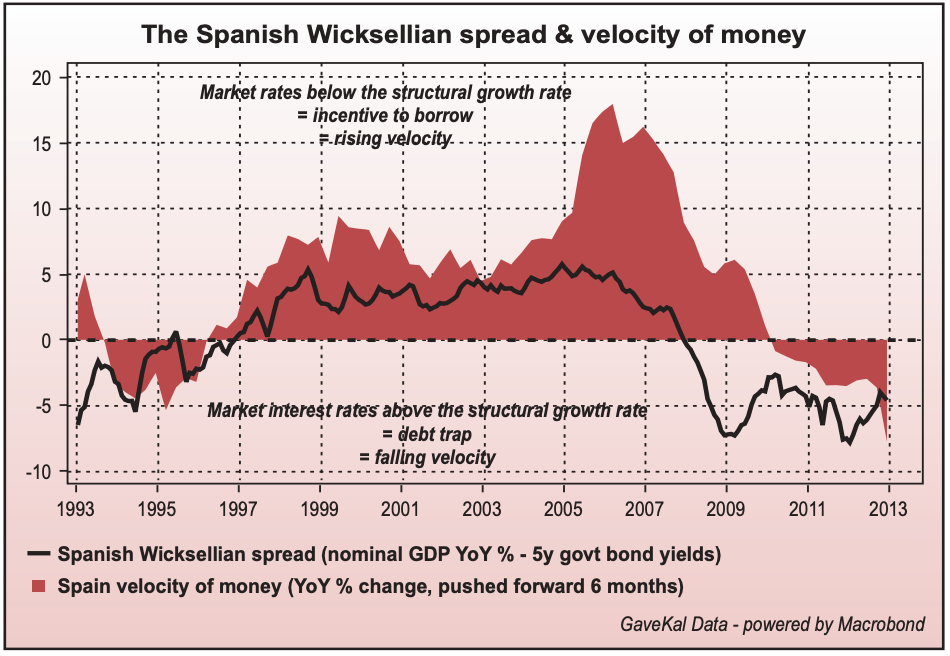

A better model of borrower behaviour is that offered by the so-called Wicksellian spread. It’s named after Swedish economist Knut Wicksell who argued that there is an invisible “natural rate of interest” that causes the supply and demand for capital to clear:

Wicksellian spread = Natural rate of interest - interest rateAnd so, how do you calculate this invisible “natural rate of interest”?

French economist Charles Gave argues that the natural interest rate can be approximated by the returns on capital for the average BBB-rated company. It can also be approximated by nominal wage growth or nominal GDP. Charles Gave’s reasoning is that if average companies can make a positive return from borrowing and investing - they will do so. Or if households can make a positive return from borrowing and investing in wage proxies like rental houses, they will also do so.

The conclusion is that if the interest rate is way below returns on capital for companies or way below wage growth for households, then the private sector will probably borrow. And with higher borrowing, you’ll get excess money sloshing around in the economy, causing the inflation rate to rise.

4. Inflation statistics are inaccurate

“One of the things I'm pretty convinced of based on our analysis is that inflation is under‐reported in China by as much as 4 to 5% a year … if the inflation figures were wrong, then this would also apply to the levels of economic growth the country was enjoying” - Jim Chanos

Governments justify persistent inflation with the argument that as long as citizens maintain their purchasing power, then they won’t be hurt by the inflation.

But one problem with that argument is that inflation is almost impossible to measure. And even if it were possible to measure it, governments are incentivised to conceal the true inflation to avoid voter backlash.

Another problem with the argument is that asset price inflation is typically neglected by central banks. So even if consumer price inflation is low, a loose monetary policy can cause some people to get rich while the rest are unable to compete when it comes to buying a house or affording, say, college tuition.

The inflation rate is usually approximated by the change in a consumer price index (“CPI”). A government agency identifies a broad basket of goods that consumers typically buy. It then uses surveys to measure how the prices of the goods in the basket change over time.

But as Mobius points out, CPI has several key flaws that make it an inaccurate metric:

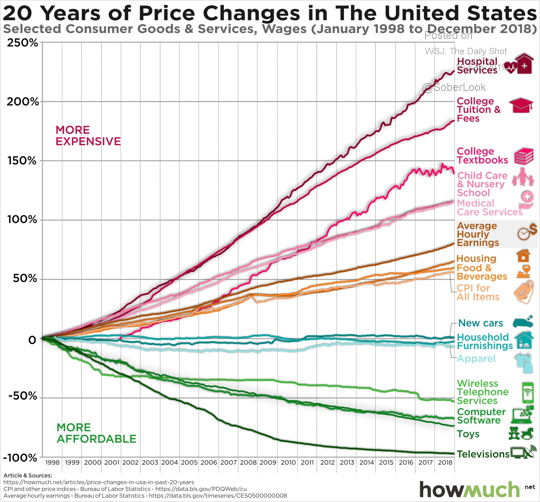

- The first problem is that CPI excludes certain goods and services, such as mortgage costs and out-of-pocket costs for medical care. Other related metrics, such as “Core CPI” and “Core PCE”, ignore food, energy and other important categories. Further, many of the fastest-rising expenses for households tend to be underweighted in CPI measurements:

- Second, the basket of goods changes rapidly. It’s impossible to update the basket in real time. For example, a study showed that 44% of online sales in a given year were goods that didn’t exist the year before. How can the basket be adjusted properly to account for such rapid shifts in consumption?

- Third, most CPI calculations perform so-called hedonic adjustments. For example, if the price of a steak rises, the government assumes that consumers will simply purchase a cheaper substitute, like hamburgers. Or if the price of a memory chip goes down, CPI is adjusted downwards, even though most consumers will just buy the latest computer instead and not notice any difference.

- Fourth, inflation statistics are backwards-looking. They don’t tell you what the current inflation pressures are like - only what inflationary pressures were in the past.

- Finally, CPI calculations are based on what people say they buy - not what they actually buy. Who knows whether consumers are truthful or not?

So even if governments want to target the inflation rate to ensure constant purchasing power, it’s easier said than done.

And governments may not even want to tell you the truth in the first place. This inaccurate representation of inflation helps governments deceive their citizens about the true nature of the economy, as economic growth is measured in real terms after subtracting a somewhat arbitrary inflation measurement like the GDP deflator.

5. Governments love inflation

“By a continuing process of inflation, government can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens” - John Maynard Keynes

Governments are comfortable with a moderate level of inflation. The shift to fiat currencies and the central bank setting of interest rates has enabled them to spend money above what has already been raised through normal taxation.

With fiat currencies, they can now promise their voters spending programs they care about without facing the challenge of raising taxes. This is particularly useful in developing countries where tax systems tend to be unsophisticated.

Another reason for governments to push for higher inflation is that voters will be tricked into thinking they are progressing when their compensation rises. They may not realise that their costs are probably rising even faster.

Let’s also not deny the fact that big businesses often lobby their government to keep spending on specific areas. And as inflation surprises to the upside, businesses will also benefit from a lower labour cost. We saw that in Weimar Germany in 1919-23 when the real labour cost fell 40-60% vs the pre-inflation era. You can find my post on that topic here:

If the inflation rate gets too high, voters will eventually revolt. For example, Germany’s hyperinflation of the early 1920s left a scar in the national psyche causing Germans to remain prudent borrowers. And the generation that lived through China’s hyperinflation of the early 1940s became suspicious of paper money for decades to come.

Today, governments seem to think low single-digit inflation is the sweet spot. They will argue that a little bit of inflation is good for the economy, even though - as Mobius points out - there is no proof that this is actually the case.

Inflation is simply a compromise that enables politicians to get re-elected, help them favour vested interests and boosts real economic growth calculated by subtracting inflation rates that are probably underestimated in the first place.

6. Inflation causes redistribution of wealth

“[Inflation] discourages all prudence and thrift. It encourages squandering, gambling, reckless waste of all kind. It often makes it more profitable to speculate than to produce. It tears apart the whole fabric of stable economic relationships. Its inexcusable injustices drive men toward desperate remedies. It plants the seeds of fascism and communism.” - Henry Hazlitt

Inflation leads to winners and losers. That’s especially the case if inflation surprises to the upside or surprises to the downside. In such scenarios, long-term contracts that are fixed in nominal terms will benefit one party and do a disservice to the other party.

For example, if your wireless operator gives you 30-day payment terms, then if inflation surprises to the upside, you will gain by being able to pay after 30 days in depreciated currency. Meanwhile, the wireless operator giving those payment terms will lose.

Such redistribution of wealth has widespread implications and is largely neglected by the public.

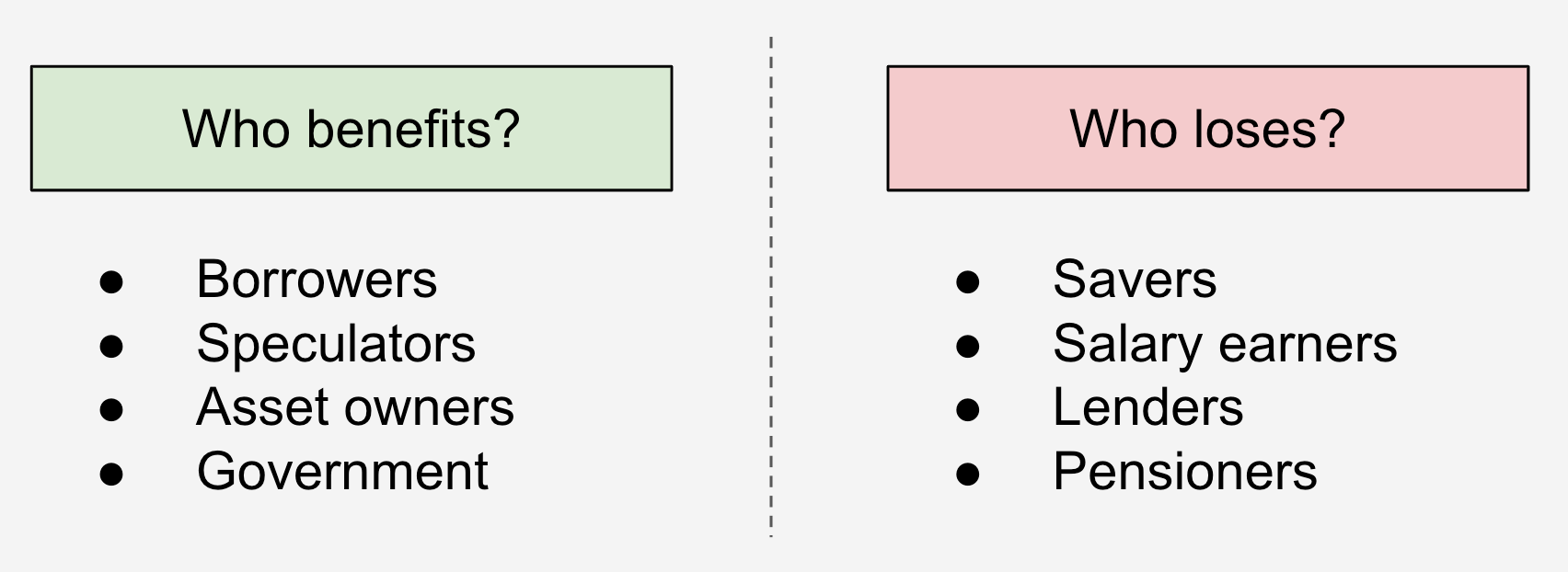

So who benefits from high inflation? Generally, the rich asset owners and speculators benefit while the hard-working middle class are on the losing end:

Specifically, these are the groups that benefit from higher-than-expected inflation:

- Fixed-rate borrowers such as corporates or the government benefit as they will receive money today and be able to pay it back through depreciated currency.

- Speculators can borrow at low-interest rates and invest in assets that grow in line with nominal incomes, for example, precious metals, real estate or stocks.

- Business owners selling products that are unregulated: Companies whose revenues are non-regulated and enjoy pricing power tend to adjust to inflation almost instantaneously. They also benefit from lower real wages, which tend to lag behind the true inflation rate.

- Governments: Inflation helps governments reduce their liabilities. And persistent government deficits help them spend beyond their means. Also, as income tax brackets and personal exemptions tend to be fixed in the short-term, inflation causes overall taxation pressures to rise, a phenomenon called bracket creep.

Who loses from higher-than-expected inflation?

- First and foremost, savers: Most individuals and businesses keep their money in demand deposits at commercial banks. The interest they receive tends to be far lower than the CPI and way below nominal income growth. So inflation can be seen as a tax on savers.

- Individuals on fixed salary: Individuals who have to bargain hard for any wage increase will be in a tough spot. Trying to keep up with inflation may require them to switch jobs frequently to battle the inertia inherent in the setting of middle-class wages.

- Lenders: Owners of fixed-income securities or lenders tend to lose from inflation. They pay out money today, but the money they receive in the future will have depreciated.

- Pensioners: Other groups that live off fixed incomes are pensioners and those that receive disability benefits. While there may be CPI adjustments in the payouts, CPI often doesn’t capture the true extent of underlying inflation.

In my view, this redistribution is hard to justify from any moral standpoint. It creates a perverse incentive structure that no doubt weighs on productivity.

If economic actors spend more time trying to benefit from this ongoing redistribution of wealth rather than being productive, society-wide prosperity will decrease.

7. Inflation protection might not be enough

This discussion takes us to my final point:

If inflation statistics understate the true nature of inflation, then any asset whose value is linked to consumer price inflation will be at risk.

Early on in my career, I worked in corporate finance, advising companies and funds on their acquisitions of infrastructure-related assets, including utilities, railroads, toll roads, airports and so on.

Such regulated assets typically have CPI adjustments in their revenue line that protect investors from currency devaluation. If Mark Mobius is right that CPI understates true inflation pressures, investors in such assets will eventually lose out.

Meanwhile, any company with true pricing power, such as consumer goods companies and owners of real estate, will be able to raise their prices much faster - not only in line with CPI but with overall wage growth. Which - as Mark Mobius points out - has almost always been higher than CPI.

The philosophical argument behind CPI-linked “inflation protection” doesn’t make sense either. Who cares if your CPI adjustment allows you to buy a similar number of television sets or sweaters in the future? What matters for investors is the opportunity cost they face in choosing to invest in one asset over the other.

If goods producers or owners of real estate can raise prices faster than regulated assets, then those stocks should trade at much higher multiples today. So be sceptical whenever someone claims that CPI adjustments will adequately protect against currency devaluation.

8. Conclusion

Since central banks were introduced in the 19th and 20th centuries and currencies ceased to be backed by gold and silver, inflation has become a recurring theme in our lives.

While we might be close to the end of the long-term debt cycle, COVID-19 has shown us that governments are totally capable of raising their budget deficits to excessive-, World War 2-type levels. High inflation rates may well continue.

Don’t buy into the idea that CPI-linked assets protect your purchasing power. It’s usually better to own wage proxies like real estate. Or companies whose revenues are unregulated and have enough pricing power to raise prices in line with wages. And across the cycle, we should probably avoid fixed-income assets such as bank deposits and maybe even bonds, too.

Asian Century Stocks is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.