Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

- China has two domestic stock exchanges: Shanghai and Shenzhen. But getting approval to list domestically can be difficult.

- There’s also the option to list overseas. Besides Hong Kong, the largest market by far for Chinese companies to list overseas is the United States.

- Companies listed in the US tend to use depositary receipts to gain access to capital, often through complex Variable Interest Entities (VIEs) structures.

- There’s been a crackdown on companies in several sectors, including technology, education and property development. It’s unclear whether this crackdown is over and what role private enterprises will play in tomorrow’s China.

- I’ve identified 12 companies among China’s ADRs that qualify as “hidden champions” - companies that dominate their niches and enjoy strong competitive advantages. While frauds are common, I’ve tried to exclude them from the list.

My previous posts on hidden champions in Singapore and Hong Kong were well received.

The concept of “hidden champions” was introduced in Hermann Simon’s book Hidden Champions of the 21st Century. It refers to companies dominating their respective niches. Common denominators among such companies include high earnings growth and high returns on capital.

In today’s post, I’m shifting my attention to Chinese companies listed in the United States. Most of these companies are not directly listed but trade through so-called American Depositary Receipts (ADRs). Let’s see whether it’s possible to find hidden champions among them.

Table of contents:

1. China’s overseas listings

2. The Chinese ADR market in 2023

3. A shift in the political landscape

4. Screening for candidates

5. Hidden champions among China’s ADRs

6. Conclusion1. China’s overseas listings

When Chinese companies have wanted to raise capital, historically, they’ve chosen to do so at China’s two domestic exchanges: Shanghai and Shenzhen. But due to difficulties in gaining approval for a domestic listing, some companies instead choose to raise capital overseas.

There are many hurdles in doing so. For example, China’s capital controls make it difficult to repatriate capital raised overseas back into China. If a company wants to list its shares overseas directly, it will need regulatory approval. And finally, there are foreign ownership limits for companies operating in sensitive areas such as technology, media and education.

Chinese companies have become increasingly adept and navigating this environment. One solution has been to raise capital through so-called depositary receipts. These are certificates issued by banks that represent ownership of the underlying shares. Dividends get passed on to the holders of the depositary receipts at the ratio at which they represent the underlying. Those listed in America are known as American Depositary Receipts (ADRs), and those elsewhere as Global Depositary Receipts (GDRs).

It’s worth making a distinction between sponsored ADRs and unsponsored ones. With sponsored ADRs, the company has a formal agreement with the bank that creates them. Unsponsored ones are where banks choose to issue depositary receipts on their own. These tend to be illiquid. And since they’re not considered securities under US law, they do not need to file reports with the SEC.

The first Chinese company to list in America in 1992 used this structure: the automaker Brilliance Automotive, which would later form a joint venture with BMW in China. Brilliance issued depositary receipts against underlying shares of a Brilliance subsidiary in Bermuda, which only owned part of the entire group.

The next part of the development of China’s ADR market was in the year 2000. That was the year when China Telecom was listed on the NYSE as part of a push to impose market discipline on its state-owned enterprises.

That same year, the Chinese tech company Sina Corporation devised a way to get around China’s foreign ownership restrictions: Variable Interest Entities (VIEs). Since China’s law prohibits foreign ownership in sensitive sectors like technology, Sina set up an offshore company in the Cayman Islands that had an agreement with Sina’s main business in China to transfer profits.

Following Sina’s innovation, many Chinese tech companies were listed in the United States, including Baidu in 2006 and Alibaba and JD in 2014.

VIEs are controversial. Many Chinese ADRs using such VIE structures pay out capital previously raised overseas, and their dividend yields tend to be low. Many Chinese investors call ADRs “concept stocks” (概念股).

In the early 2010s, a series of accounting scandals among Chinese overseas listed companies shook the market, including Sino-Forest in Toronto and Longtop Financial. The SEC started paying attention and has been trying to improve the quality of accounting in overseas listed Chinese companies.

After President Donald Trump’s Executive Order 13959 in 2020, it became illegal for American citizens to own shares in Chinese military-linked companies. This included Chinese telecom companies such as China Telecom, and they were therefore forced to be delisted from the NYSE.

That same year, we also saw the introduction of the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act. This law states that companies that prevent the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) from conducting inspections will be delisted from US exchanges. But so far, they’ve been given access to all audit records requested. That means the delisting risk is off the table, at least for now.

2. The Chinese ADR market in 2023

Hong Kong remains the biggest market for Chinese companies to raise capital overseas; many companies are listed directly.

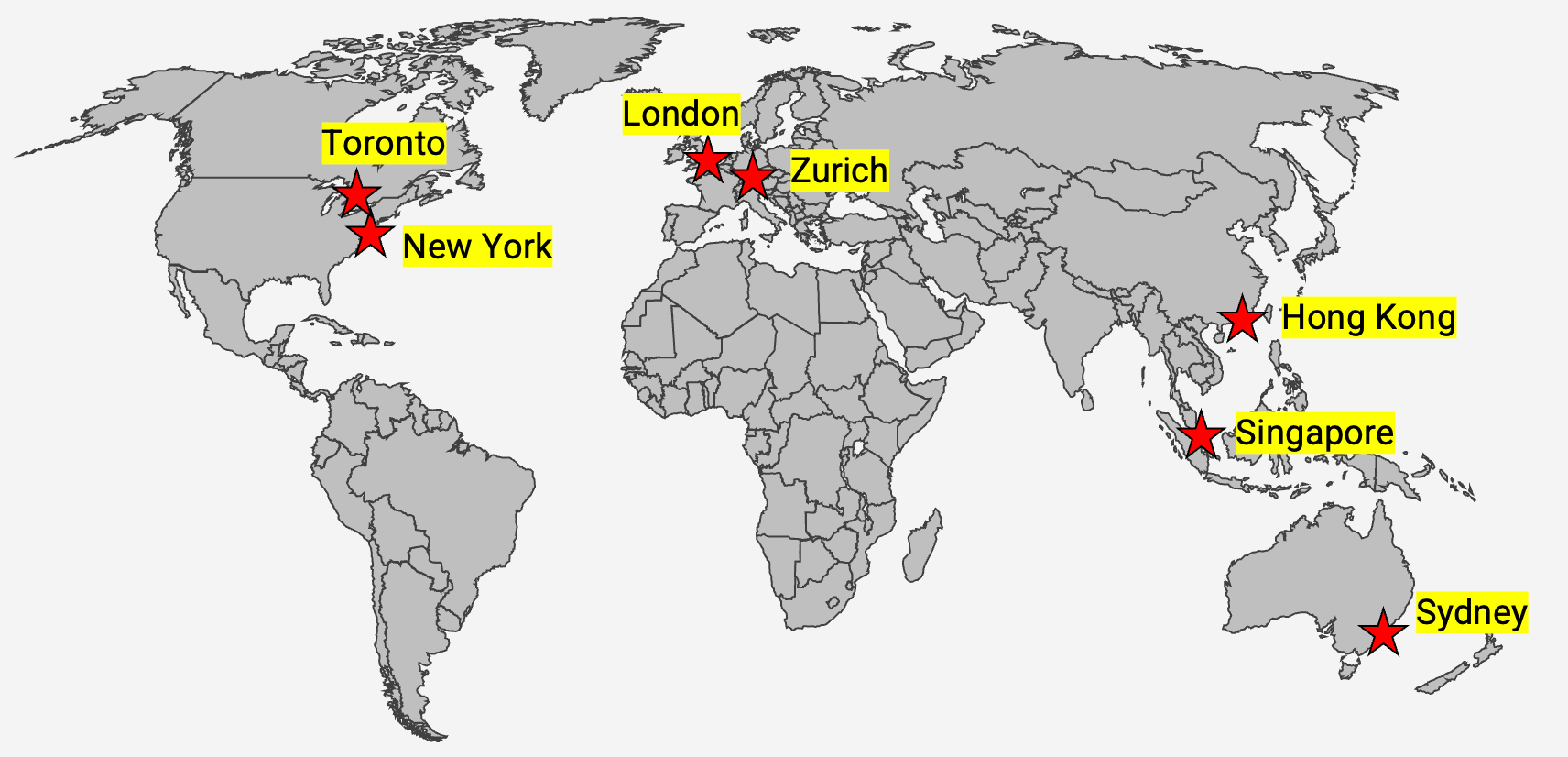

The United States is the second-biggest market for Chinese overseas listing by far. Meanwhile, while Chinese companies are listed in London, Singapore, Zurich, Toronto and Sydney, these are much smaller markets.

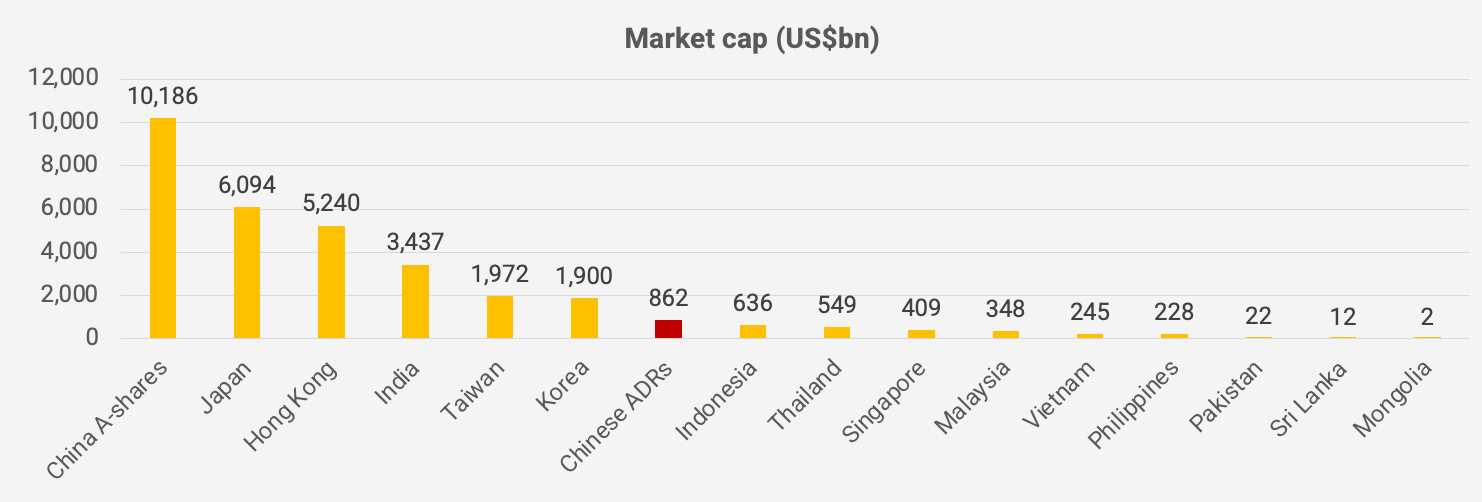

Summing up the market caps of all Chinese companies listed in the United States, you get to US$860 billion, making the market bigger than Indonesia but smaller than South Korea.

The performance of the ADR market has been horrendous in the past two years. And even over 15 years, the index has been largely flat. And with few dividends paid, for that matter. Here is a chart of the S&P China ADR index from late-2001 until today:

This index now trades at a forward P/E of 15.0x, price/book of 2.0x and a dividend yield of 0.3%. That may not sound low, but tech companies tend to be faster-growing and difficult to value using traditional valuation multiples.

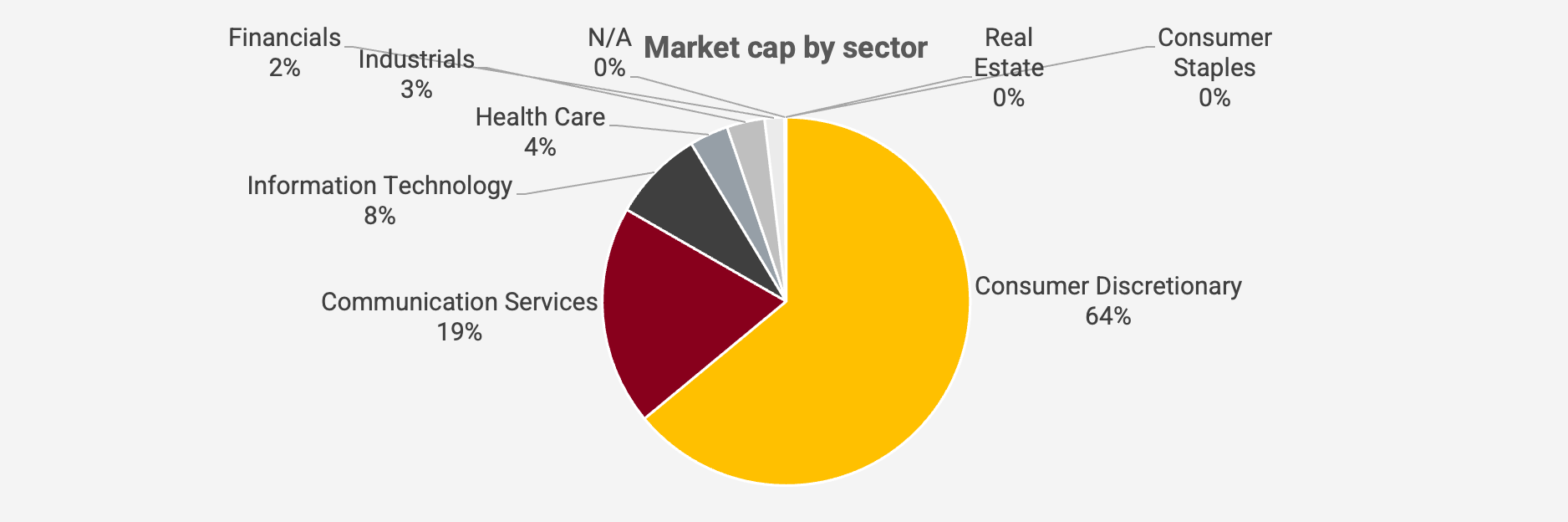

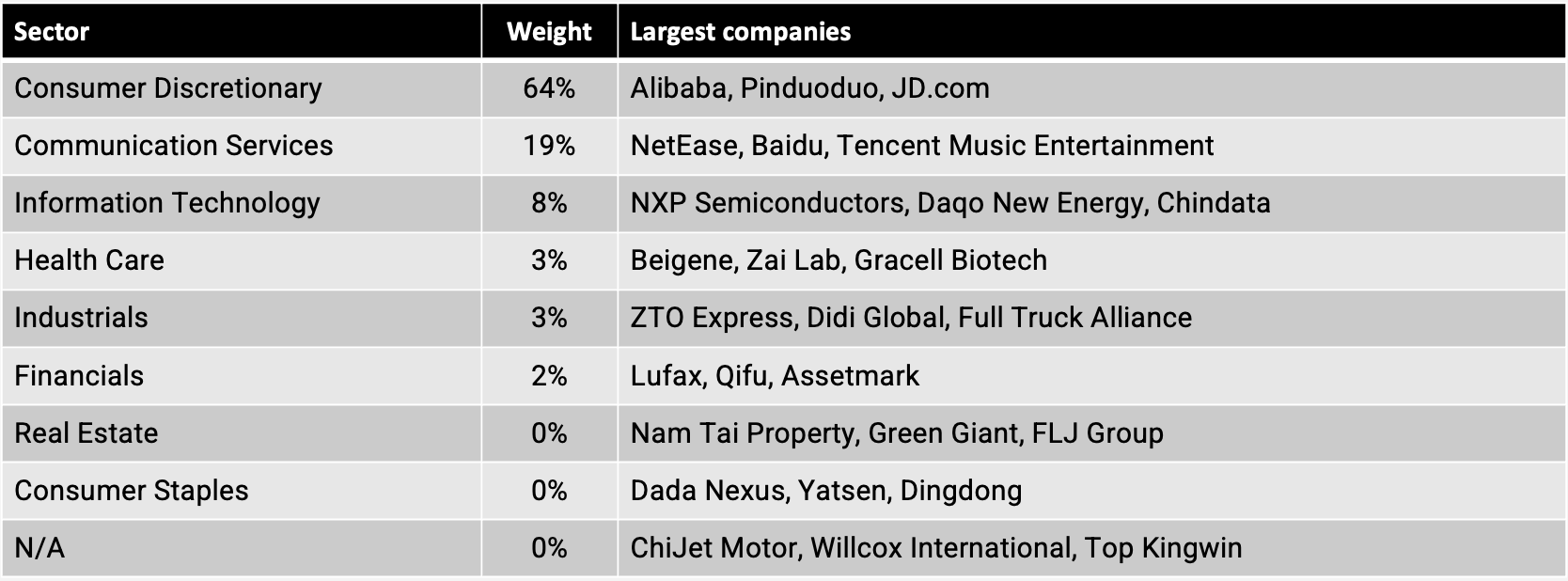

In total, there are 376 Chinese companies listed in the United States, but most of these are small. Applying a US$50 million market cap minimum will leave you with only 148 ADRs. Here is a sector split for these stocks:

But within the sectors called “consumer discretionary” and “communication services” you’ll find many tech companies such as Alibaba and JD.com. Here are the largest companies in each of the above sectors.

3. A shift in the political landscape

I think it’s worth pointing out the shifts we’ve seen in the political landscape over the past few years. The poor performance of China’s ADRs might reflect US sanctions, a weaker Chinese economy and poor investor sentiment. But it’s also related to a set of crackdowns that began in 2020.

Since Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in the late 1970s, the government has become increasingly committed to private-sector entrepreneurship. A key turning point was the 1988 regulation on private enterprises, which allowed anybody to start a company.

But since Xi Jinping became General Secretary in 2012, China has turned more socialist. An early sign of this shift was in bank lending from 70% to private enterprises in 2012 to just 30% in 2016, according to Nicholas Lardy.

More recently, the Communist Party has been pushing for all private companies to institute Communist Party committees, including subsidiaries of foreign companies. The delineation of responsibilities between the company board and these party committees is unclear. The idea is that the party committee in each company will “executive the will of the party”. And from my understanding, they will also have a veto on hiring decisions.

That’s why I was concerned when the crackdown on Chinese tech companies began in late 2020. Since then, many CEOs have resigned, although we don’t know exactly why.

In some cases, these resignations occurred right after the government received “golden shares” in the company, most notably at Bytedance before Zhang Yiming resigned a month after. But the resignations have been industry-wide: other than Zhang Yiming, we’ve also seen Jack Ma at Alibaba, Richard Liu at JD, Dowson Tong at Tencent Music Entertainment, Colin Huang at Pinduoduo and Su Hua at Kuaishou resign.

The Communist Party has also cracked down on other sectors. For example, tuition centres were declared illegal overnight, causing companies engaged in that sector to become practically worthless.

And from late 2020, private property developers have been cut off from credit, justified through the so-called Three Red Lines document. Whatever the intended purpose, the result has been that private developers are going bankrupt en masse, with their remaining assets slowly gobbled up by state-owned enterprises.

This has made me question private enterprises' role in tomorrow’s China. It’s possible that the crackdowns that occurred from 2020 to 2022 were part of a gamble to consolidate power in the run-up to the October 2022 Party Congress.

A more cynical view would be that state-owned enterprises will be favoured from now onwards, while private companies pushing forward the Party’s Made in China 2025 vision will be tolerated.

But it’s also possible that much of this negative news has already been priced-in. A glimmer of hope was provided by central banker Guo Shuqing in January 2023 when he said that the crackdown on Chinese tech companies was basically over. Is he right? Only time will tell.

4. Screening for candidates

Just like previously, I like to screen for my hidden champions using three main metrics:

- The historical average return on equity

- Growth in earnings per share

- Share price performance

But given the complex realities of running a business in a communist country, I’m looking for businesses aligned with the Communist Party. Specifically, companies that are not at odds with party supremacy or the plans set out in Made in China 2025.

I’m also looking for companies with sustainable competitive advantages - companies whose products or services are unique and add value to customers.

The following ten companies score the highest in terms of historical return on equity: