Fraud in Asia

A review of Tan & Robinson's 2014 book. Estimated reading time: 24 minutes

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

Tan & Robinson’s book Asian Financial Statement Analysis is probably the definitive book on how to spot fraud and misrepresentation in this part of the world.

Be careful of companies with high margins, poor cash flows, fast-growing balance sheets and complex corporate structures with frequent related party transactions.

I have great respect for the detailed work that short-sellers carry out. In my experience, high-profile short-seller reports should always be taken seriously.

Perhaps the most important factor for any investment in Asia is assessing corporate governance. There are few books on the subject, making it difficult to navigate.

I was thrilled to read Chinhwee Tan and Tom Robinson’s Asian Financial Statement Analysis. The book is from 2014 and discusses real-world examples of fraud and misrepresentation across Asia.

Tan has experience as a forensic accountant and collaborated with his former professor, Tom Robinson, to write this book. And in my view, it remains the best book on the subject.

In this post, I’ll discuss what I learned from the book and what you should be careful of when investing in the region.

Table of contents

1. The basics

1.1. Overstating earnings

1.2. Overstating financial position

1.3. Overstating operating cash flow

1.4. Managing earnings

1.5. Corporate governance issues

2. Case studies

2.1. Satyam

2.2. Sino-Forest

2.3. Longtop Financial

2.4. Olympus

2.5. Oriental Century

2.6. RINO International

2.7. Oceanus

2.8. China Biotics

2.9. West China Cement

2.10. Harbin Electric

2.11. Renhe Commercial Holdings

2.12. Duoyuan Global Water

2.13. Winsway Coking Coal

2.14. PUDA Coal

2.15. Sino-Environment Technology Group

2.16. Real Gold Mining

2.17. Fibrechem Technologies

3. Conclusions1. The basics

Let’s start with the basics. Modern commerce is built on accounting, specifically the double-entry accounting system developed by Luca Pacioli in the 15th century. Just like fingerprints are used to solve murder cases, double-entry accounting can determine where a financial crime has occurred.

The so-called accounting equation tells us that:

Assets = Equity + LiabilitiesThis is important because it means that if any item changes on the asset side of the balance sheet, you’ll also see an effect on the liability side and vice versa. Changes to balance sheet items can give us clues of what’s happening.

The three financial statements - the income statement, the balance sheet and the cash flow statement - are interrelated.

For example, net profit from the income statement ends up in retained earnings on the balance sheet. Cash flow from operations is derived from the net profit figure. It also ends up as cash on the balance sheet. So, you’ll need to review all three financial statements if you want to get a grip on the changes in the conditions of a firm.

Tan & Robinson argue that there are five categories of accounting games that companies can play:

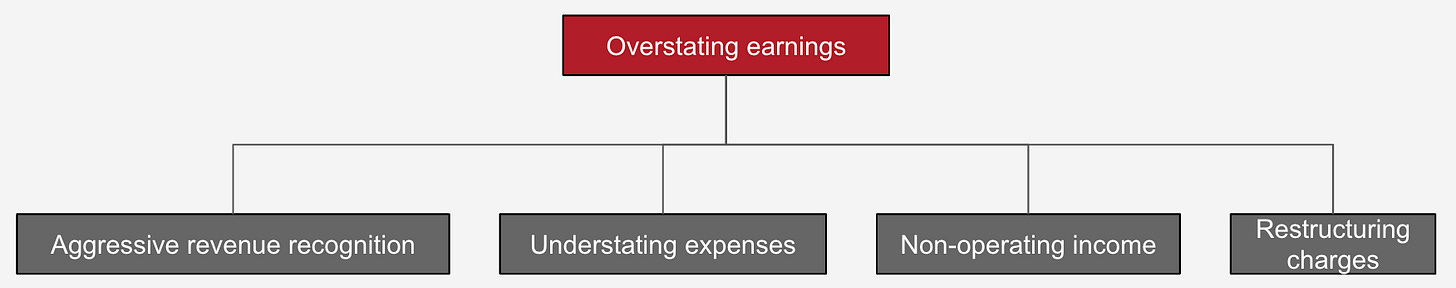

1.1. Overstating earnings

Companies can boost earnings through either aggressive revenue recognition or deferral of expenses. They can also reclassify non-operating income as revenues or operating expenses as “restructuring costs”, but it’ll be obvious the second you open the income statement.

Regarding aggressive revenue recognition, search for the footnote describing those policies and compare them to the company’s peers.

You’ll also spot aggressive revenue recognition on the balance sheet. Since profits from fictitious revenues end up in retained earnings on the balance sheet, accounts receivables will typically grow. So, you should compare the year-on-year growth in accounts receivable with those of the revenue line. Or look at the number of receivable days vs the company’s peers.

The rise in retained earnings can also be matched by entirely fake cash balances. In that case, they’ll have to produce fake documentation and try to hide the fact that the cash isn’t bringing in any interest income. And you should be particularly careful of companies that classify cash in unusual ways, like the Indian IT company Satyam did.

When it comes to understating expenses, dishonest companies either avoid reporting them altogether or defer them to a later period. For example, they might have sister companies taking on the burden of payroll.

Understating expenses also leads to higher retained earnings on the balance sheet. And it’ll often be matched on the asset side through overvalued inventory. You’ll spot this trick by comparing the number of inventory days with the company’s peers.

Understating expenses can also be done by capitalizing costs rather than expensing them. For example, costs might end up in property, plant & equipment or in unusual categories like “deferred customer acquisition costs”. It’s worth looking at strange movements in such balance sheet items and see whether they should be written down.

Key takeaways: Earnings manipulation takes place through aggressive revenue recognition or understating expenses, and to spot them, you should review balance sheet items like accounts receivables and inventories.

1.2. Overstating financial position

This takes us to the next point: companies can manipulate the size of their balance sheet, often to improve leverage ratios or specific ratios like return on equity.

For example, a company could move liabilities off the balance sheet through special purpose vehicles (SPV). After the SPV has been de-consolidated, the leverage doesn’t seem as high. However, the company might still guarantee the debt inside the SPV and thus still be liable.

Another common way to reduce perceived leverage is to enter into operating leases. Today, IFRS 16 forces the capitalization of operating leases, too. But outside of IFRS 16, classifying a lease a operating rather than capital lease will help improve leverage ratios. A typical example is an airline leasing aircraft and not consolidating the debt onto its balance sheet.

But what I’ve most commonly found in Asia is that companies reduce their ownership in subsidiaries below 50% and then opt for equity method accounting. This type of accounting removes the debt from the balance sheet and only records the subsidiary’s net assets. It’s common in the Chinese property development industry.

Management can also play around with assets measured at “fair value”. For example, there’s some leeway in measuring the value of financial assets, biological assets, land and buildings, etc. You’ll have to go through the footnotes to understand which methods are used and whether those methods are appropriate for that particular situation.

Key takeaways: Companies can use tricks to hide true indebtedness. Look for keywords such as “equity method”, “special-purpose entities”, “joint ventures”, “associated companies”, “nonconsolidated entities”, “guarantees”, and “commitments” to spot such games.

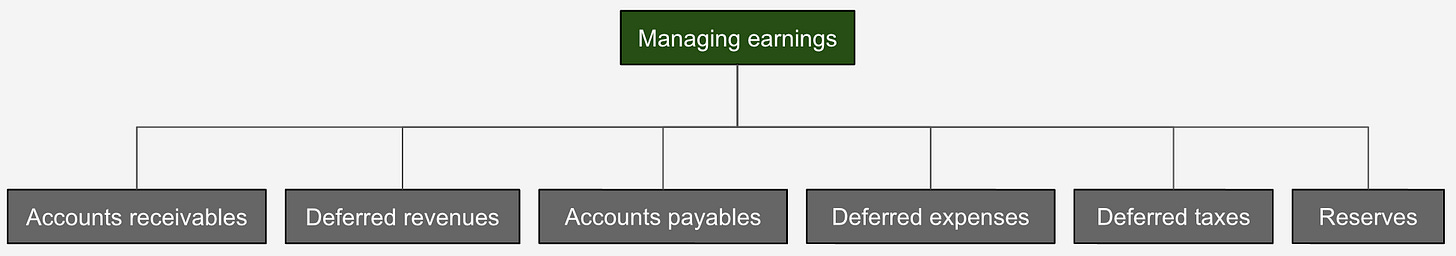

1.3. Managing earnings

While companies can fabricate earnings through various methods, they can also shift earnings from one period to another. They use specific balance sheets like accruals or deferrals to achieve this. The purpose might be to protect the share price by covering up a weaker quarter.

Here are the balance sheet items that are typically used to manage earnings volatility:

Accounts receivables: Change estimates for bad debt expense and earnings will change a bit on the margin.

Deferred revenues: Avoid recording revenue later, even though the funds have already been received.

Accounts payables: Take on more expenses in the current period even though the company hasn’t paid for them yet. This can include payroll, rent, taxes, etc.

Deferred expenses: For example, classifying marketing expenses as “deferred customer acquisition costs” is common in the insurance industry.

Deferred taxes arise from differences in how profits are recorded in the financial and tax statements. Watch out for deferred tax assets since they could imply profitability issues.

Contingencies & reserves: A company can set up cookie-jar reserves after an acquisition, enabling it to save income for a future year.

Key takeaway: If a company records very little margin volatility, you might want to dig deeper into these accruals and deferral items to see whether the company might smoothen earnings through accounting tricks.

1.4. Overstating operating cash flow

Tan & Robinson make the case that some companies actively try to move around items in the cash flow statements to boost operating or free cash flow.

For example, they might stop paying suppliers or selling accounts receivables and classify that sale as operating cash flow. Or classify operating expenditures as capital expenditures.

I pay great attention to the operating cash flow and try to compare it with the net income. This ratio should be higher than 1x on average, since you add depreciation & amortization to net income to get to operating cash flow. But if you do, just be aware that operating cash flow can be manipulated in particular years.

You’ll also want to check the free cash flow, i.e. the operating cash flow less capex to understand cash generation. If it’s consistently negative, you’ll probably want to see a high return on equity to prove that the capex yields some return.

Key takeaways: Check the items in cash flow statements to make sure they belong in the right section, for example interest income should be in the financing section and not the operating section.

1.5. Corporate governance issues

This final category has to do with how insiders can enrich themselves at the expense of minority shareholders. Tan & Robinson argue that we should look at the following factors when assessing corporate governance in the region:

Board governance: A board with a majority of external, independent board members.

Shareholders rights: Equal voting rights given to minority shareholders

Interlocking ownerships: Cross-shareholdings and other relationships between companies in the group.

Related-party transactions: Transactions between companies within the larger group or between management and the ListCo.

Structure: Variable interest entity structure or direct ownership of equity?

Excessive compensation: Management enriching themselves at shareholders’ expense.

Personal use of assets: For example, the CEO’s family lives in a property owned by the company.

Lack of transparency: Disclosures are insufficient to understand major transactions or the condition of the company.

Auditor issues: Qualified opinion, auditor hired by management for consulting services or too close of a relationship with the firm, etc.

Key takeaways: Always check the corporate structure, related party transactions and other conflicts of interest.

2. Case studies

Now, let’s jump into the juicy part of the book, where Tan & Robinson discuss precedents. And most importantly, what you could have done to spot each fraud.

2.1. Satyam

India’s Satyam used to be one of the largest IT consultancies in the world prior to the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. That fiscal year ending in March, revenues grew at a rate of +46% year-on-year.

But the company was found to have falsified revenues. The clue was that its accounts receivables grew much faster than revenues. Short-term receivables grew +51% year-on-year, long-term receivables +80% year-on-year and unbilled revenues +111% year-on-year.

An unusual item on the balance sheet called “investments in bank deposits” was treated separately from cash. It didn’t earn much interest, which was suspicious in and of itself.

Key takeaway: If you see fast growth in accounts receivables or unusual cash items, check the revenue recognition policies and whether reported growth is realistic or not.

2.2. Sino-Forest

The Sino-Forest scandal was high-profile and kicked off investigations of many Chinese frauds in North America in 2011-2013. Several high-profile investors, such as John Paulson and Richard Chandler, were hurt by the downfall of Sino-Forest.

It was supposedly China's largest private forestry operator, with 790,000 hectares of forestry assets. The company had listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange through a reverse merger and then raised about US$3 billion through debt and equity. By 2011, it traded at a market cap of US$4.5 billion. It showed amazing financial metrics with EBITDA margins as high as 60-70%.

In June 2011, Carson Block’s firm, Muddy Waters, released a report accusing Sino-Forest of fraud, and the stock fell by over 80%. An independent committee was formed to investigate the fraud allegations. And in the end, only 18% of the timber holdings were confirmed by plantation rights certificates.

The investigation also found that most of the revenue came from related parties that acted as middle-man between Sino-Forest and its customers. These were described as “authorized intermediaries” though not identified.

So, what was the giveaway? The lack of cash flows in Sino-Forest’s financials. It invested heavily in Timber Holdings, funded by debt and equity raises. The timber holdings balance rose by +43% in 2010. And the fact that it used “authorized intermediaries” meant no third-party verification of its transactions. It’s also worth noting that management only owned about 3% of the company - a tiny amount compared to outside shareholders.

Key takeaway: Watch out for companies with a lack of cash flow, inexplicably high margins and unidentified intermediaries acting on behalf of customers.

2.3. Longtop Financial

Chinese banking software developer Longtop Financial was brought down by Andrew Left’s Citron Research in 2011. It had reported operating margins of 49% and impressive growth.

However, Citron pointed out a few issues with the company. It had set up a new business called Xiamen Longtop Human Resources that employed the majority of staff at Longtop Financial. But its accounts weren’t consolidated into the ListCo. This sister business was fully disclosed in its SEC filings.

After Citron released its report, Longtop announced a share buyback. Auditor Deloitte responded by trying to verify its cash holdings. But as soon as they went to Longtop’s banks, Longtop fired its auditor on the spot.

After Citron confirmed that its SEC financials did not match those of its government SAIC filings, NYSE suspended the stock from trading.

In hindsight, the warning signs should have been Longtop Financial’s high gross margins of almost 70% - way higher than any of its peers.

Clearly, Longtop had simply shifted costs to its sister company, Xiamen Longtop Human Resources. It was also noteworthy that the owner had transferred 70% of his shares to employees and friends after the IPO, perhaps to pay off hidden liabilities. After its IPO, it had engaged in 20 acquisitions, most of which were unprofitable entities and purchased from unidentified individuals.

Key takeaway: Watch out for companies with inexplicably high operating margins and with tight relationships with sister companies whose accounts aren’t consolidated into the ListCo.

2.4. Olympus

Olympus is a Japanese manufacturer of precision machinery - no doubt one of the highest-quality companies in Japan. However, in 2011, it was discovered that the company had covered up a significant loss on its balance sheet after Japan’s bubble burst in 1990. The loss was about JPY 100 billion or nearly US$1 billion at the then-prevailing USD/JPY exchange rate.

Olympys’s trick was this: its 1990s loss had been kept off its books by transferring the financial assets not consolidated into the ListCo. These other companies bought the assets above fair market value using money borrowed from Olympus. Later, when changes in accounting rules forced Olympus to consolidate these companies, it was forced to acquire them at high valuations.

The only clue was significant goodwill on Olympus’s balance sheet after repurchasing the overvalued assets. Goodwill is recorded whenever an asset is acquired above book value. And in Olympus’s case, the difference between the price and book value was significant.

The story unravelled after a new CEO joined in 2011, and he alleged that management had significantly overpaid for acquisitions. He was fired, but an investigation proved him right, and write-downs soon followed. The stock dropped by over half and remained weak for several years.

Key takeaway: Watch out for when goodwill exceeds equity by a significant margin.

2.5. Oriental Century

Oriental Century was a Singapore-listed operator of schools in China, including Oriental Pearl College, Humen Oriental and Nanchang Oriental. In 2006, Singapore’s Raffles Education bought a 29.9% stake in Oriental Century but remained a passive investor. The first of the schools was owned by a related party called Dongguan Baisheng, owned by the CEO Yuean Wang and other insiders. The ListCo earned a management fee for operating Oriental Pearl College but did not own the asset.

After the Great Financial Crisis in 2009, Oriental Century restated its past results. CEO Yuean Wang acknowledged that two of the schools had operated at losses, that the company had inflated sales and cash balances and also diverted money to a related party. Wang was swiftly terminated as CEO, and the CFO quit as well. A PwC audit showed that revenues over the preceding five years had been just CNY 20 million, compared to the reported CNY 329 million. The company was liquidated the following year.

Key takeaways: Be careful of transactions with related parties, especially when they’re owned by senior executives. Not owning all operating assets within the ListCo should be a warning sign.

2.6. RINO International

RINO International was another target of Carson Block’s Muddy Waters. The company was engaged in wastewater treatment equipment with amazing gross margins of 35-40% - way higher than the peer group’s 20%.

RINO’s corporate structure was complex: it owned one variable-interest entity, which in turn owned three other entities, all consolidated into the ListCo. So, the consolidated accounts should have given a true picture of the company’s condition. But as Muddy Waters pointed out, RINO’s property, plant & equipment were minuscule at just 4.7% of total assets and a small fraction of revenues.

Carson had retrieved SAIC filings showing that reported revenues were only about 5% of those reported in its SEC filings. He also proved that RINO had not fulfilled the terms of the VIE agreement.

Key takeaways: Be careful of companies producing commodity products yet show margins. Low PP&E/revenues was another warning sign. Also, be careful of companies operating with VIE structures, especially when they’re not operating in sensitive sectors like the finance or software industries.

2.7. Oceanus

Oceanus is a Singapore-listed food supplier of seafood such as abalone from its two farms in China. It was listed in Singapore in 2008 through a reverse merger. In the following two years, it showed strong top-line growth of 17% per year and the book value of its abalone assets more than doubled in two years to US$180 million. By 2011, it had achieved a market cap of US$310 million and an enterprise value of US$530 million.

But in late 2011, it issued a profit warning and wrote down its abalone assets by US$140 million. It explained the write-down by saying it had seen an unexpected increase in the mortality rate of its 200 million abalone population, with 42 million abalones perishing vs 6 million the previous year.

In actuality, between 2008 and 2010, Oceanus’s volume of abalone sold actually decreased, but the rising value made up for it. The company had essentially overstated the number of abalones, their size and the growth in the valuation of these biological assets. Meanwhile, the cash balance dropped from US$88 million in 2009 to US$4 million by 2011. The founder, Ng Cher Yew, had been a director of 3 companies that were dissolved or struck off the company register.

Key takeaways: Watch out for improper valuation of biological assets, as they’re frequently wrong. Check the background of the CEO and whether he’s been involved in fraud in the past.

2.8. China-Biotics

China-Biotics was a Shanghai-based maker of food supplements that went public in 2006 through a reverse merger. It produced probiotics, specifically acidophilus in pill format, for sale in mainland China. It also sold probiotics in bulk to the dairy and animal feed industries. In 2010, revenue grew by +50% year-on-year with gross margins of 70%. And it had a sizeable cash balance of US$132 million.

In early 2009, a short-seller pointed out that its 70% gross margins were hard to believe and that it had found large discrepancies with its SAIC filings. Later, private investigators found that many stores China-Biotics claimed to own did not exist. Finally, in 2011, auditor BDO resigned. It said it could not verify the cash balance that China-Biotics claimed to own and refused to certify the company’s 2011 numbers. After failing to file a 10-K, it entered into a trading halt.

The give-away was China-Bioti’s high margins. It was also suspicious that its inventory days were just nine days. It suggested a lack of inventory to support the scale of the business. An industry organization confirmed that China-Biotics had no footprint to speak of. It also accrued tax liabilities because it probably didn’t have taxable income in the eyes of the tax authorities.

Key takeaways: Watch out for companies with frequent CFO turnover, inexplicably high margins, low inventory days and low tax payments.

2.9. West China Cement

West China Cement is a Shaanxi-based cement company which had 17 production lines with a total capacity of 23 million tons. It was listed on AIM in 2006 and then relisted on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2010.

In 2012, it was targeted by Soren Aandahl’s Glaucus Research, who called it a “blatant fraud”. It believed that its 20 percentage point margin premium to its competitors was unreasonable and that it had been overpaying for loss-making cement factories from unidentified individuals (CNY 350/ton of capacity vs peers’ CNY 60 per ton). Glaucus also pointed out that West China Cement had high auditor and management turnover.

It turns out that Glaucus was mostly correct. West China Cement’s selling prices were actually lower than those of the industry, and its costs were comparable. Several management team members had a checkered past at Sino Vanadium, Norstar Founders Group and others. However, the company continues to operate and remains listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Key takeaways: Be careful of companies with unreasonably high margins, with frequent M&A transactions and individuals with a track record of mismanagement.

2.10. Harbin Electric

Harbin Electric is a Heilongjiang-based electric motor manufacturer selling to global OEMs or integrated systems. It grew through the acquisitions of companies such as Weihai Hengda and Advanced Automation Group Shanghai. Growth was rapid in 2010, though with negative operating cash flow.

In 2010, the board received a proposal for a management buyout by the CEO and Baring Private Equity. The CEO entered a term loan facility with China Development Bank, collateralized by his shares.

Short-sellers question Harbin Electric’s numbers. They found mismatches between SEC and SAIC filings. However, despite doubling revenues in 2010 to US$500 million, it could not disclose a single verifiable large customer. And its operating margins of 20% were far higher than any of its peers. It also entered into consulting agreements with undisclosed individuals.

Yet despite these concerns, the privatization was completed as planned, and the company is now private.

Key takeaways: Whether Harbin Electric was a fraud remains unknown. But in any case, be careful of companies with negative cash flows, unreasonably high margins and no verifiable customers.

2.11. Renhe Commercial Holdings

Renhe Commercial Holdings was a developer of underground shopping centers. It supposedly installed furniture, fixtures and equipment in government-owned underground bomb shelters and used those spaces for commercial purposes. It was listed in Hong Kong in 2008 and saw tremendous revenue growth in 2011 of +96% and gross margins of +70%.

But Renhe’s operating cash flows were weak, with a majority of profits coming from one-off gains and sucked up by rising accounts receivables. It also issued shares repeatedly throughout 2009, partly to finance the acquisition of agricultural wholesale markets from the controlling shareholder. It also sold five projects to undisclosed projects and recorded accounts receivables for them, yet never collected any cash.

Key takeaways: Be careful of business models not proven elsewhere. Check whether net profits are earned in cash. Also, be careful of companies engaging in M&A, especially with undisclosed parties.

2.12. Duoyuan Global Water

Duoyuan Global Water was a US-listed Chinese supplier of water treatment equipment. The company showed strong growth and was audited by Langfang Zhongtianjian, which had a shoddy track record.

In 2011, Carson Block’s Muddy Water issued a report claiming that its revenues were overstated by 100x, with actual revenues less than US$800,000. He had been to its factory in Hebei province and saw few signs of human activity, counting only 240 employees. He also found that Duoyuan’s distributor network was non-existent. And finally, it engaged in related-party transactions with the company’s CEO, Wenhua Guo.

A warning signal was when 4/6 independent directors resigned after management refused to provide more information after Muddy Water’s report. There were also incorrect classifications in the cash flow statement. Also, Duoyuan had zero work-in-progress inventory, which is unusual for a manufacturing company.

Key takeaways: The low inventory was a warning sign, as were repeated related party transactions.

2.13. Winsway Coking Coal

Winsway Coking Coal is a supplier of coking coal in Inner Mongolia. It was listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2010. It accumulated a debt burden that still looked reasonable with just 2x total debt/EBITDA and an EBITDA interest coverage ratio of 7.5x.

In 2011, an outfit called Jonestown Research accused Winsway of overstating its coal inventory by HK$ 1 billion in 2011 and engaging in undisclosed related party transactions with a company that had previously been a subsidiary of Winsway. By doing so, it could claim higher revenues and explain away the lack of cash on the balance sheet.

A warning sign was that the company's promoter had only listed a part of the group, keeping the most valuable parts to himself. The complex corporate structure created scope for mismanagement.

That said, it’s not clear whether Jonestown was correct. KPMG signed off on Winsway’s financials, and Winsway acquired a large Canadian coal miner called Grand Coal in a joint venture while also selling the CEO’s 30% stake to state-owned enterprise CHALCO. From my understanding, Winsway has recently changed its name to E-Commodities Holdings.

Key takeaways: Be careful of complex corporate structures and relationships with middle-man distributors and suppliers that may or may not be related parties.

2.14. PUDA Coal

PUDA Coal was a coal company providing coking coal to steel manufacturing in China’s Shanxi province owned by a certain Chairman Zhao. It had two segments: coal mining and coal washing. It was listed through a reverse merger in 2005 and then raised capital twice in 2010. It appeared to be a profitable, well-run company.

But in 2011, GeoInvesting and Alfred Little published a report on PUDA, stating that it was, in fact, an empty shell company that had failed to disclose the transfer of PUDA’s 90% stake in Shanxi Coal to the Chairman. It later sold part of that stake to CITIC Trust. The auditor resigned. And the stock went to zero.

The most obvious warning sign was that Chairman Zhao operated a separate company called Resources Group and also owned six mines in the Pinglu Project, where PUDA received most of its coal.

Key takeaways: Be careful of complex corporate structures, especially when senior management owns related businesses.

2.15. Sino-Environment Technology Group

Sino-Environment (SinoEnv) was a Singapore-listed Fujian company operating in the industrial waste gas and wastewater industries. It was controlled by the CEO, Sun Jiangrong. It had reported cash holdings of SG$40 million within mainland China.

In 2008, CEO Sun defaulted on an SG$120 million loan from hedge fund Stark Investments, which had been collateralized by his holdings in SinoEnv. This forced him to sell his entire stake and lose control.

After the new owners took over, PwC performed an audit. It found that SG$85 million of transactions made by SinoEnv were made without approval from the board, including for four waste power plants where construction had not yet begun.

Key takeaways: In this case, it’s unclear what could have warned you about the mismanagement of the company.

2.16. Real Gold Mining

Real Gold Mining was a miner based in China’s Inner Mongolia. It was listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange during the gold fever in 2009 and raised more capital in 2010. With the proceeds from these capital raises, it acquired several other miners.

A 2011 article in the South China Morning Post pointed out that the company’s 2009 accounts did not match those of its SAIC filings. Soon thereafter, the shares were suspended. It turned out that approximately HK$1.5 billion of company funds had been funneled to majority shareholder Wu Ruilin on top of personal loans to him. The ListCo had also acquired two phosphorus mines from him personally for HK$520 million. Trading in the stock was halted in 2011.

Other than the M&A transactions with Wu, the giveaway was that out of the five major customers disclosed in the IPO prospectus, only one confirmed that it had a real connection with Real Gold.

Key takeaways: Try to verify a company’s key customers. Also, be careful of frequent related party transactions.

2.17. Fibrechem Technologies

Fibrechem Technologies was a Singapore-listed company producing polyester fibers and microfiber at three plants in China’s Fujian province. Up until 2008, it appeared to be growing rapidly with high margins.

However, in 2009, auditor Deloitte refused to sign off on the company’s financial statements due to difficulties determining cash and accounts receivables. The CEO then resigned.

Three years later, an investigation uncovered accounting irregularities with overstated assets and a non-existent cash balance, which may have been embezzled. Fibrechem also had improper disclosure of assets and liabilities. It also uncovered a transfer of a controlling stake in a subsidiary out of reach of creditors.

The warning signs were excessive cash reserves about the company’s size. In addition, it kept borrowing money despite its large cash position. And the operating margins were double those of its closest peers.

Key takeaways: Question companies selling commodity products at high margins. And question companies with large cash piles that keep raising more debt for some reason or another.

3. Conclusions

Tan & Robinson’s book Asian Financial Statement Analysis was like a blast from the past. I highly recommend it if you want to up your game when spotting fraud and misrepresentation.

The main takeaway from the case studies in the book is to be careful of companies with inexplicably high margins, poor cash flows, fast-growing balance sheets and complex corporate structures with frequent related party transactions.

Trying to avoid fraud altogether is difficult. But I’m hopeful that if we’re mindful of the typical warning signals, we can at least avoid the worst offenders, the ones that actually end up going to zero.

If you would like to support me and get 20x high-quality deep-dives per year and other thematic reports like this, try out the Asian Century Stocks subscription service - all for the price of a few weekly cappuccinos.

This is great stuff! Also like the summary of key concepts and the overall structure!

Thanks for the great review and summary of key concepts!