Book review: Asia's Investment Prophets

A book from Claire Barnes about with investor perspectives on pre-crisis Asia

Claire Barnes's book Asia's Investment Prophets is a historical document.

It was written in 1994 and published in 1995, just before the Asian Financial Crisis. Since it’s now out of print, it’s difficult to find and costs US$189 on Amazon. So to spare you from buying the book, I thought I should give you a summary of the key insights I absorbed from the book.

The book is an Asia 1990s version of The Market Wizards. It features 16 interviews with famous fund managers at the time, as well as a profile of an insurance company operating in Hong Kong at the time (I left this part out of my review below as I thought it didn’t add much value).

What makes the book special in my view is not just the historical perspective, but also the fact that it was written right before the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997. Some cautious investors saw the crisis coming and hedged themselves appropriately. Others bought into the hype.

I also tried to track down every investor featured in the book by Bloomberg, Google and other public sources to see where they are today. Some investors remain successful even today. And many of those who suffered excessive drawdowns didn’t live to see another day.

This is the story of 16 investment prophets on the cusp of one of the greatest financial crises the world has ever seen.

Backdrop

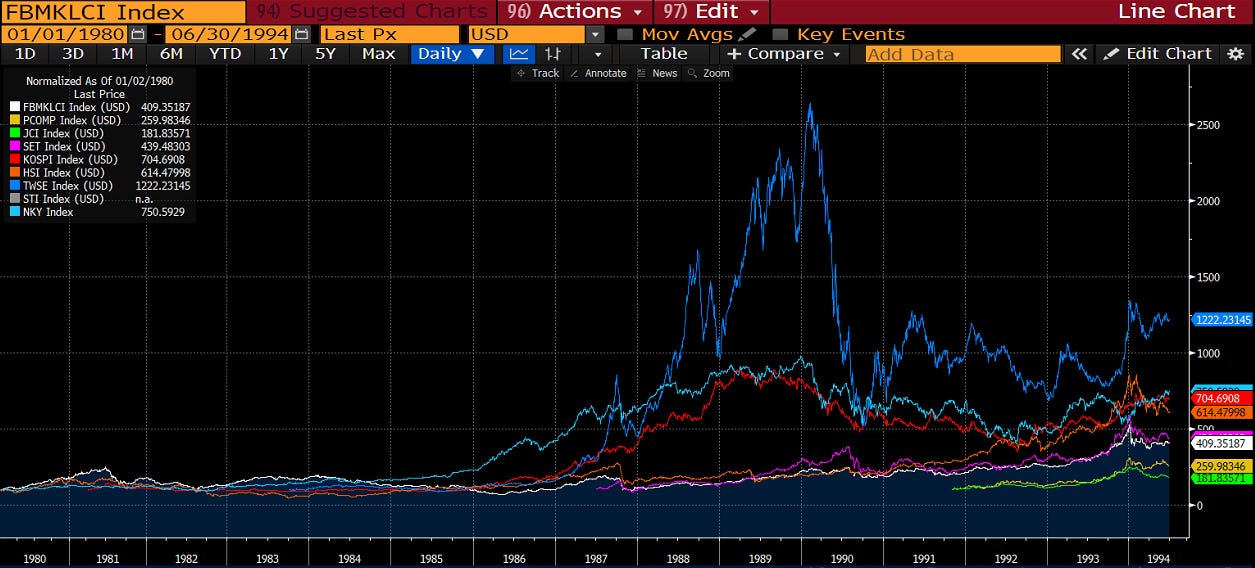

Claire Barnes book was written in 1994. The major East Asian stock markets such as Japan, Korea and Taiwan rallied throughout the 1980s, peaking around the turn of the decade. The culprit was an easy monetary policy in Japan, with credit flowing into financial assets. Some of that money found its way into Korea and Taiwan, which at that time had just begun to open up their capital markets to foreign investors. A mania ensued, as I wrote about in this post about the 1980s bubble in Taiwan.

From the vantage point of 1994, many investors felt that it was now Southeast Asia’s turn to outperform. Malaysia and Singapore had had a massive rally in 1993. Hong Kong’s stock market, on the other hand, was climbing a wall of worry, especially as the handover to the People’s Republic of China was getting closer.

With stock prices getting into more dangerous territory, fund managers looked for bargains elsewhere, in Thailand, Korea and small caps. Others felt that growth was so strong in this part of the world that it did not matter whether P/E multiples came up a bit. Valuation multiples in Southeast Asia still had a long way to go to reach the levels of Japan in 1989.

I will now give you profiles of each of the fund managers featured in the book, together with their outlooks for the future as 1995 was rapidly approaching.

1. Peter Phillips, Fidelity

Fidelity’s Peter Phillips was known as one of the most analytical stock-pickers in Hong Kong at the time. Originally from Australia, he ran the Hong Kong / China fund for 3-4 years and achieved astounding results. By the mid-1990s he had taken over Fidelity Funds South-East Asia.

Fidelity was a large fund manager and one of its key advantages was having its in-house dealing function. Fidelity also had specialised software for harmonising and comparing portfolios. After studying the previous day’s market movements and an hour of administrative work, Phillips would spend the rest of the day analysing companies.

And stock picking is where Phillips excelled. Country specialists on the ground would send him ideas and he then spent time parsing through their reports. Together with his team and country specialists, he had managed to narrow down the list of 11,000 listed companies in Asia to 400 that he thought deserved their attention. Phillips personally visited 250-300 company meetings each per year - making him possibly the most hard-working of any fund manager in Hong Kong at the time.

Just like his American colleague Peter Lynch, Phillips’s stock-picking approach was completely bottom-up. He claimed that even though he ignored macroeconomic factors, he was still able to understand the broad picture from the data points he collected from individual companies.

While he was primarily looking for undervalued companies, he also wanted to understand why a company was cheap. Understanding the regional history, social trends and the background of the families involved helped.

South China Morning Post was a key holding in his fund, though he had reduced the position now that Robert Kuok had taken over the company in 1993. But he still loved the stock. At home in Hong Kong, Phillips had been counting the number of advertising pages in the Saturday edition and found that it was up 10% for the year to date. Could the increase in the number of advertising pages perhaps presage an earnings beat? He thought it might. He also liked the paper’s new state-of-the-art plant in New Territories, which in addition to South China Morning Post could also be used for Chinese publications at a later stage.

In the early 1990s, Phillip’s favourite market by far was Taiwan. After the big crash in the early 1990s, prices had come down to more reasonable levels. He described it as the largest emerging market in Asia: big, illiquid and poorly researched. He also thought that many Taiwanese companies would benefit from the opening up of China. Compared to companies in Hong Kong, Taiwanese companies were operations-focused, less status-conscious and often run by engineers or other people with strong technical qualifications.

One of the Taiwanese stocks he liked was Standard Foods, which was listed after the management buy-out of the old Quaker Oats business. A major trend in Taiwan was a great focus on health, with consumers turning to Standard Foods healthier offerings. He also liked the fact that the CEO had a PhD in food science. For a company growing close to 25% per year, a P/E multiple of 18x was certainly not excessive.

Another sector he really liked was life insurance. Premium income in Hong Kong at the time was growing at 27% per year for the prior decade - not bad for what has traditionally been seen as a “difficult market”.

2. Adrian Cantwell

Global Asset Management’s (GAM’s) Adrian Cantwell was described in the book as a “relaxed and sociable figure”. While running a high-pressure hedge fund, he also managed to find balance in his life, spending time on weekends with his three young children and a stunningly beautiful wife.

A key differentiating factor about the GAM organisation was that it required him to spend practically no time on marketing. He knew his objective: to make money in absolute terms while avoiding losses and preserving capital.

Even though Cantwell had an absolute return mandate, he had a long bias and did not trade excessively. Once he found a company with decent prospects for earnings growth, he bought at a low P/E relative to its historical trading range. And then hold the stock for years.

Just like the team at Fidelity, Cantwell visited 200-300 companies per year. What did he look for? Through his company meetings, he looked for an overall impression of the business, management style, management logic and the broad business direction.

He was especially cautious about corporate governance:

“Throughout the whole of Asia, you are always at risk of the main shareholder acting to the disadvantage of minority shareholders.”

As an investor - he admitted - there’s not much you can do about it. If you eliminated all companies that were less than perfect, the available stock universe would be too greatly reduced. And so the pragmatic side of Cantwell won out, with him conceding that sometimes “one [still] has to be prepared to play the game”.

One stock that Cantwell liked was Hong Kong airline Cathay Pacific. The airline was a very well-managed company in his view and had fallen to a low level compared to its historical range.

By 1994 Cantwell had turned cautious. Specifically, when it came to Singapore and Malaysia, stock prices had run too far:

“Malaysia was extraordinarily overvalued, and Singapore didn’t look fantastic relative to cash.”

He felt that most of the stories had become conceptual and that brokers were looking three or four years out to justify their recommendations, compared to just one or two prior. That was usually an ominous sign.

3. David Lui

Hongkonger David Lui (雷賢達) had one of the best long-term track records in Hong Kong by the mid-1990s. He had studied at the London School of Economics and worked for a number of financial institutions before taking over the Schroders Asia Hong Kong Fund in 1985. In the following ten years, the Schroders Asian Fund had compounded at a rate of 30% per year, resulting in an increase in net asset value of over 13x. It was an extraordinary track record.

A key part of Lui’s investment strategy was playing the cycles. He combined that with broad diversification and a low turnover of just 20%. He never cared about index weights and was willing to make large bets as long as he believed in something. For example, from 1989 to 1993, he made a massive bet that the Hong Kong property market would boom. That bet ended up being massively profitable for his fund.

In the interview, Lui stressed the need to meet management and do basic research. In his own words: “Young analysts often only look at financials and ignore rapid changes in the competitive environment”. He took the example of Hong Kong’s pager companies doing well in 1993. But once Motorola and NEC stepped into the market, the smaller players would have to cut their prices and see their margins shrink. So he felt that a fuller picture of the competitive environment was needed in your analysis rather than just focusing on the numbers.

Lui bought into Singapore shipyards in 1986 when nobody else paid attention. At the time, the Singapore government had written it off as a “sunset industry”. Earnings had been in decline for over half a decade. But Lui believed that a cyclical turn was coming. He rode the cyclical upturn up to the peak in 1989.

One of Lui’s favourite situations was buying after a major political risk had been absorbed by the market. He was an aggressive buyer after the Tian’anmen protests in 1989. He bought again in 1992 when Thailand had a coup. He felt that most political changes actually did not have a major effect on a country’s development. So once the market starts to worry about politics, that’s usually the time to buy.

Lui believed that interest rates would move higher towards 1996-97. In 1993, he became cautious on Hong Kong property developers for that reason, thinking that the property cycle had turned. Interest rates had reversed. The growth in the Chinese economy had peaked out temporarily. And the supply of land in Hong Kong was about to increase.

How about the Hong Kong stock market? His view was that valuations in Hong Kong were unusually high compared to historical levels. Short-term, he was cautious, advising friends to wait for more opportune market conditions.

Lui was also worried about the handover over Hong Kong to China:

“We still have the 1997 problem, and some people will continue to leave the country. It doesn’t take much to change the market, with prices at such a high level.”

The markets that Lui was more bullish about were Korea and Taiwan. He felt they were well-equipped to take advantage of the rising demand for high tech products, something that could not be said for Hong Kong, Malaysia or Thailand. In addition, Koreans and Taiwanese were well educated and hard-working people and that would eventually show in their countries’ development.

4. Colin Armstrong

Jardine Fleming’s Colin Armstrong was described by his competitors and colleagues as “the best bull market fund manager in Asia”. He believed that Asia as a whole remained in a structural bull market, despite some recent wobbles in 1994.

He moved to Japan from Hong Kong in 1984 to take over the small-cap and technology team at Jardine’s. After he realised that the best profits were made elsewhere, he switched to the Japan Trust, which had a broader mandate. It performed incredibly well throughout the later parts of the Japanese bull market. While his fund was hurt by the downturn in 1990, he pulled a lot of money out and transferred it to a new long/short fund called Jardine Fleming Ninja Trust. That helped cushion the blow of a weakening Japanese stock market.

In 1991, Armstrong left Japan, claiming that the decision was “mostly out of boredom”. He moved down to Hong Kong and assumed the leadership of Jardine Fleming’s Pacific Regional Group. His performance over those first few years was great.

Armstrong described his own strategy as “starting off entirely macro, and then try to fit the micro to the macro”. If you find a lot more interesting companies in a particular market, then something is wrong with your macro view.

His stock-picking approach was basically: buy the stocks that promised the fastest earnings growth while having the best story. Within a broader basket, he felt that approach would work out well. He felt he almost had a duty to stay bullish.

“People put their money into Asian markets because the economies are growth economies, and so by definition you are a growth fund manager… you are destined to underperform perpetually [if you buy conservatively-run blue-chips].”

In terms of the organisation, he emphasized optimism among his employees:

“You should be positive about things. If you believe something’s right to do, you should do it… I don’t see any point in giving money to managers who take a neutral view… The key to doing well as a fund manager is to try to have a positive view.”

In 1995, he believed that bull phases were going to be longer and stronger than bear periods. Over the course of a cycle, he believed that an aggressively bullish view will outperform. And that in the meantime, Jardine Fleming’s funds would feature at the top of league tables far more often than at the bottom.

Still, despite his bullish tendencies, he viewed Japan as being in a long-term bear market:

“I don’t people will see a new high in the Japanese market for the next twenty to thirty years.”

He was betting that other Asian markets were still at a developing stage. They hadn’t yet seen the type of asset inflation and multiple expansion that characterised Japan’s stock market bubble. How much will stock markets outside of Japan rise? Armstrong believed that most of the Asian markets would rise another 3-400% in the next five years. So you have just to stay bullish to capture most of that upswing.

5. William Kaye

Bill Kaye was described as a brash American newcomer on the Hong Kong investing scene. Swinging into town in 1991, he thought he was on the leading edge of Asian investment. At dinner parties, he would repeatedly tell people that his hero was Gordon Gecko. He cultivated a similar tough-guy image for himself.

Kaye spoke in disparaging terms about money management in Asia, which he described as “plain vanilla”. His own firm on the other hand sought absolute returns, aiming to outperform in all markets. He had a particular interest in derivatives, a market that he felt was immature in Asia in the early 1990s.

Kaye’s pedigree was excellent. He studied economics at Vanderbilt University and joined Goldman Sachs in the M&A department in 1977 after an MBA at the University of Chicago. Though he had decent deal exposure at Goldman, including working on the first-ever LBO, he left within 1 year and joined the risk arbitrage department of Paine Webber in 1978. The firm’s track record under Bill’s tenure was excellent with close to 25% per year returns and 75-100% with leverage. But in an unlucky series of events, Paine Webber was burned by the failed takeover of United Airline’s parent in 1989, which led to losses and Bill leaving his job.

Convinced that China was the greatest macro story in the world, he then teamed up with Jack Perkowski to start the Pacific Alliance Group in Hong Kong, backed by Tiger Management.

Even though Bill Kaye came to Hong Kong at a time when Asian markets were starting to get hot, he wasn’t a true believer:

“The time to buy the public companies in China or the Indian subcontinent is when for some reason, usually investor sentiment or very negative capital flows, you have reason to believe they are artificially depressed… You want to get there when they are dirt cheap, and nobody knows how to price anything… We’re not in that environment right now in almost any emerging country, and we haven’t been for a while… Now I wouldn’t touch anything in the Philippines.”

He was also bearish on Japanese stocks:

“How do you support valuations, with the market on 85 times earnings. If earnings doubled, the market would still be expensive. And what would cause the doubling? Not exports, because they export the worse the currency situation gets.”

Any bullish views? Yes, he saw potential in Korea. Valuations were compelling, and Koreans were lower-cost producers than Japanese. He also felt that the New Zealand macro picture was excellent, with projected growth of 4-5%, low inflation and high real interest rates. The currency eventually had to appreciate. And he also thought that the Malaysian Ringgit was a “safe bet”.

He was bearish on Hong Kong property, however. He though home prices could probably fall 20-25%:

“Why would you buy Hong Kong property shares? It’s got to be one of the most expensive cities in the world in which to operate.”

6. Edward Kong

Edward Kong’s (江志聖) EK Investment set up shop in Hong Kong in 1991. Kong was a Hongkonger who went to the University of Chicago and then to Schroders in Hong Kong, running the Schroders Asia Hong Kong Fund before David Lui.

David Lui described Edward Kong as the best fund manager he has ever known. Many others remarked that he had a remarkable knack for market timing. The various funds under Kong’s management had compounded over 30% per year since 1983.

Just like Bill Kaye’s firm, Edward Kong’s hedge fund focused on absolute returns. But unlike Kaye’s firm, Edward focused on value investing. He would form a core portfolio of stocks and then control the risk of the portfolio by hedging individual markets where he thought they were expensive and take advantage of arbitrage opportunities.

Kong thought that US investment techniques cannot be used in Asia. He took the example of Warren Buffett relying on 10-K’s. In Asia, there simply isn’t enough information. And the market environment can change quickly. Other issues include unpredictable government policies and even fraudulent misrepresentation. Over here, it was foolish to put 20% of the portfolio in a single stock and wait ten years for it to work out.

One home run was Edward’s investment in Swire Pacific, the holding company. At the time, investors focused solely on the company’s P/E ratio. But with Swire’s largest holding Cathay Pacific losing money, the P/E ratio did not tell a great deal about the company’s underlying value. And Swire Pacific’s P/E ratio was lower than even its largest subsidiary Swire Properties. He felt it was a no-brainer.

Another win was buying Hutchison Whampoa in 1984 when the market was crashing due to the Sino-British negotiation. Hutchison fell from HK$24 to HK$8. With HK$4 in cash and earnings of HK$2.5, he felt that the downside was protected - especially since prospective earnings growth was about 25% per year and Li Ka-Shing was a well-respected steward of capital.

Another win was textile stock Winsor, which in 1983 traded at 3x earnings and a 17-18% yield. He had calculated the asset values of the company’s properties as well as its textile quotas and felt that he had enough margin of safety to bet big.

After the Tian’anmen crash of 1989, Kong switched heavily into property stocks.

“I don’t have any more foresight than others as to whether there would be a civil war. I wasn’t bullish or bearish; I had no idea what would happen. But I was sure that property stocks would outperform.”

Thanks to his team’s investigative research, Kong was one of the few fund managers in Hong Kong that managed to avoid the bankruptcy of Carrian (the “Enron of 1980s Hong Kong”). It was a difficult time for him personally. He faced considerable pressure at Schroders to participate in the stock’s rise but luckily he managed to withstand those pressures and stay away from the stock.

From the 1994 vantage point, Kong was cautious. He viewed Indonesia as abnormally risky because of poor liquidity. He ruled out Taiwan and Korea because of the barriers to foreign investors and possible premiums for stocks with foreign ownership limits.

Instead, he put his money into Singapore and Thailand, as he found companies there that he viewed as cheap. It didn’t matter that the markets might be overvalued - he cared about stocks in the portfolio and not the broader macro picture.

7. David Chrichton-Watt

Watt was probably the most unassuming of all hedge fund managers portrayed in the book. He was a trekker, with experience hiking all across Asia. He first moved to Asia in 1972 working for stockbroking firm J Ballas in Singapore. He then moved to Hong Kong in 1975, again working in a brokerage firm before setting up his own fund management company in the early 1980s.

He had made three famous calls:

He was early into Thailand, where he started buying personally in 1982. At that time, good quality companies could be picked up for one to 1.5x cash flow. In the late 1970s, the bank deposit rate was 18% and the dividend yield on stocks was even higher. Watt was almost the only buyer and the liquidity was horrendous. He couldn’t even get custody for his shares and had to persuade Siam Commercial Bank to set up a custodian department for him. Financial statements had to be collected in folders from auditors. He waited for several years before the Thai market really took off in 1985.

He shorted the Japanese market at 38,000 when the bubble finally burst in 1989 and covered the position at 19,000. Perfect timing.

He was an early buyer of Sri Lanka from 1991 onwards. Watt visited Sri Lanka in the early 1980s but was deterred by political violence until the 1990-91 period. When he visited Colombo, he decided that volumes on the stock market were so low that the only option was to buy privatisations. So he bid for a distillery company, a television company and eventually Asian Hotels Corporation, which owned the Oberoi, the Renaissance and the Intercontinental.

The last year had been spectacular - up 120% in 1993. And this strong performance was achieved despite Watt buying puts all the way up to protect the downside.

By the mid-1990s, Watt managed about US$200 million, with about half from George Soros. But his broader outlook was dour. He couldn’t find stocks of reasonable value and felt that direct investments were more attractive.

“Now everything is picked over, down to darkest Africa, and we have these floods of mindless research. I don’t want to pay four times book value and twenty times cash flow.”

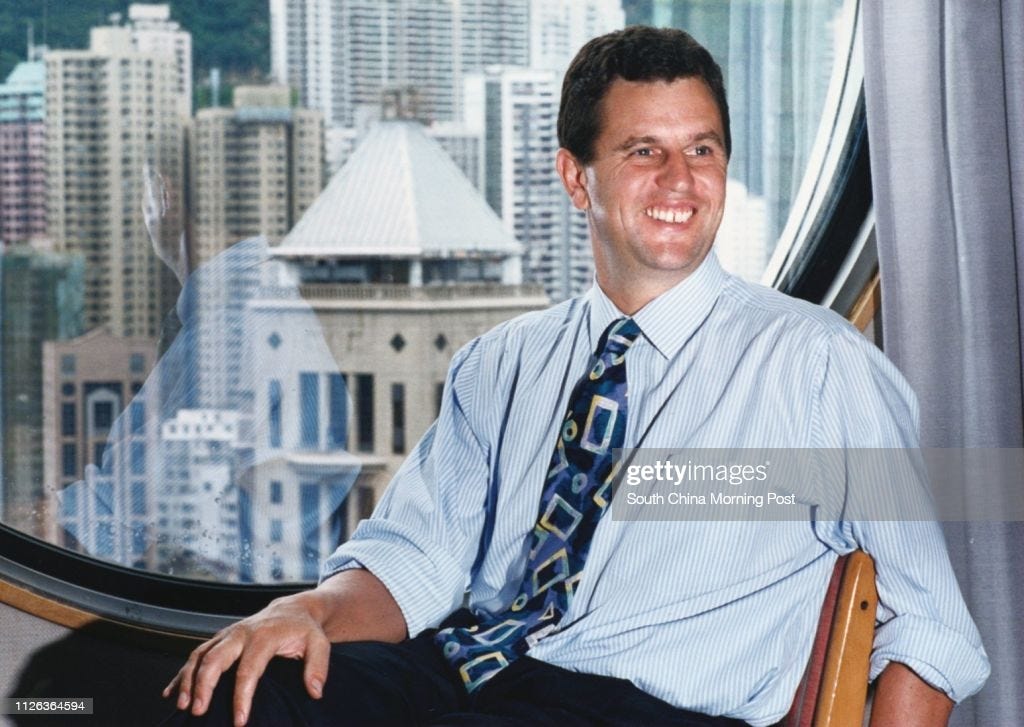

8. Peter Everington

Everington is most famous for inventing the “Asian Tigers” name for the newly industrialising economies of East and Southeast Asia. But he was also an excellent fund manager who created an enviable track record throughout the 1980s, most of the time at fund manager GT Management. Coming from the UK, he felt that while he may not have much Asia experience, he knew how to manage money.

A previous colleague referred to Peter Everington as “his most difficult trainee ever” saying that he was “absolutely impossible, he would not listen.” But somehow he stuck around long enough for management at GT to take notice of him.

Everington initially covered UK equities for GT after university. He then moved to San Francisco where he teamed up with colleague Jim Mellon to help GT set up US investment portfolios. Eventually, Mellon and Peter Everington both moved to Hong Kong, where they worked for a few years before teaming up to form Regent Pacific in 1991. Everington would be in charge of the fund management operation.

Everington had a talent for spotting long-term trends. In late 1985, he predicted a major bull market in South-East Asia due to a rising Japanese Yen and a falling oil price. The “Tiger Fund” was set up to take advantage of this new trend.

By the mid-1990s, Everington thought that the bull market could be close to over:

“These days you cannot say that the Asian markets are cheap; they’re not cheap at all… That’s why I’m moving away from plain vanilla towards risk-managed products.”

He thought that the key culprit was all the money flooding out of America, driving up asset prices. At the same time, American expertise had lead to a flourishing derivatives market, which Everington thought could help him navigate riskier waters.

Everington pointed out how inefficient markets in Asia were at the time. In January 2014, the Merrill Lynch India Fund on the London market went to a 20% premium to the net asset value. That would have been normal for closed-end funds, but this was an open-ended fund(!) So he was able to short it on Thursday night and subscribe to the fund on Monday at asset value, making 17% per cent in just four days.

Another favourite play was to take advantage of foreigners buying stocks in Korea in shares that exceeded the foreign ownership limit. Due to these foreign ownership limits, foreign shares traded at a premium to the local share price. Every once in a while a foreigner would sell the shares straight into the market without realising he or she could have made 10% by dealing over-the-counter with other foreigners. In these instances, Everington would step in, buy the shares and sell in the OTC market for a 6.5% gain in less than an hour.

He also felt options in Hong Kong were excessively priced during the mid-1990s. They traded at 45-55% implied volatility compared to New York’s 8-9% and Tokyo’s 16%. So he would take advantage of the wild swings in implied vol and hope that they would eventually mean-revert.

Another favourite tactic was to take advantage of the fact that the Hang Seng index was calculated once a minute. So Everington set up a computer system that would calculate the index on a real-time basis, giving the company a thirty-second advantage, helping them understand how the bid-offer spread was moving relative to last traded prices.

From Everington’s vantage point, the build-up in liquidity to the mid-1990s was worrying. Hong Kong’s exchange rate mechanism gave it no ability to adjust to the monetary inflow. In the preceding six years, the monetary base had risen sixfold and from August to October 1993 alone it had risen 50%. He felt that eventually, the process would go into reverse and lead to a massive crisis.

He didn’t agree that the Hong Kong market was cheap. Much of the earnings came from property developers, who were enjoying unsustainable margins based on land purchased many years ago. Property accounted for 40% of bank assets in Hong Kong banks, compared to 30% at the previous 1981 top. He felt a hard landing seemed more likely than a soft one. And then you had the issue of Hong Kong’s handover to the People’s Republic of China in 1997, which he thought could potentially lead to a panic of some sort.

South Korea looked a lot better. The market was still below its high five years ago and he felt that the economy would be capable of sustaining fast growth. On a price/cash flow basis (price divided by net profit + depreciation), the Korean market was half the price of any other Asian market. And Korea’s money supply was starting to accelerate.

Do you have to be sophisticated to invest in Asian markets? No, said Everington:

“It’s nothing as sophisticated as overseas, you just have to be a little bit ahead of the market. It’s wrong to be too far ahead; otherwise you’re probably like Marc Faber - indefinite timing.”

9. Michael Sofaer

Sofaer was the longest-established Asia-focused hedge fund manager at the time with roughly US$600 million under management. Most of the money was in the specialised Arral Asian Fund. But he wasn’t actually based in Asia. He traded from his comfortable home at Belgravia Square in central London. But that had worked out well for him.

Others described Sofaer as the “perfect English gentleman”, even though he was originally from Baghdad. After working at Schroders as an analyst for a few years in both London and Hong Kong, he left the company at age 26 to set up his own firm. He travelled to New York to learn more about the hedge fund industry and met with George Soros and Michael Steinhardt. Upon returning to Hong Kong, he set up his own company backed with US$1 million by George Soros.

Sofaer’s approach was all about fundamentals. Buying inexpensive stocks while making sure that they met basic quality tests. Stocks that seemed cheap needed to be thoroughly examined. And he was wary of leverage. Finally, Sofaer was willing to be patient waiting for the value to be unlocked.

His track record was decent, with a 17% compounded return for his global fund from 1980 to 1994 against 11% for MSCI World with much lower volatility. The last five years for the Arral Asian Fund until 1994 had given him a 29% CAGR, again with low volatility and at the top of the league tables.

Unlike the stock pickers at Fidelity, Sofaer paid a great deal of attention to liquidity changes, monitoring a range of indicators. His three analysts did the stock-picking while he was more in charge of broad asset allocation.

Like many others, Sofaer turned cautious by the mid-1990s:

“While we do not underestimate Hong Kong’s resilience, there are too many accidents waiting to happen for us to be long this market. We are long at present as we feel a meaningful rally in the US from oversold level may help Hong Kong higher, but our medium-term outlook is not bullish and we would anticipate being net short the market over the next few months.”

10. Kerr Neilson

Sydney-based Platinum Asset Management was founded in 1994 by South African Kerr Neilson with funding from George Soros. He started his investment career at a pension fund in London in 1973 but after a few years decided there were no prospects of making any money. He moved back to South Africa working for a fund management company and later set up the research department for a brokerage firm. But his negative views on South Africa led him to eventually move to Australia and join Bankers Trust.

Neilson’s track record running the retail funds of Bankers Trust in Australia for many years was excellent. In the five years prior to 1994, Neilson’s International Fund had recorded an annual growth of 25% per year, putting him at the top of international league tables.

Neilson was a sceptic by nature: conservative and cautious. He wanted stocks that were out of favour or neglected by the market, perhaps because of an unfavourable short-term outlook for the industry or recent mistakes by management. He was also looking for change: something that will improve the long-term earnings picture, whether that be technology, government regulation or competition.

He had been an early buyer of Thailand, buying stocks in the mid-1980s on P/Es of around 5x. Many of the stocks such as Siam Cement rose by over ten times in the subsequent decade. Likewise, he was early into Indonesia at a time when only four or five stocks were available to foreigners.

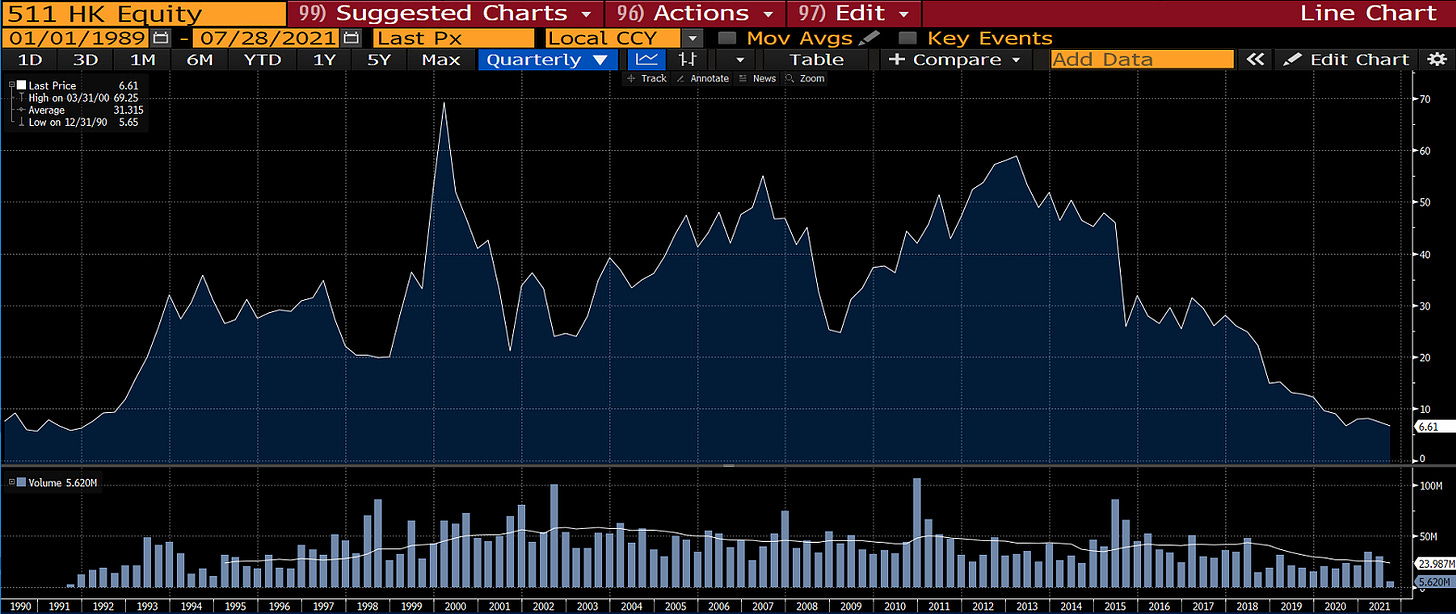

Where did he find value in the early 1990s? Neilson was excited by Hong Kong television station TVB (“Television Broadcasts”; 511 HK). It was reliant on cyclical advertising revenues and growth had been weak the precedent three years until 1991. Competing stations were also poaching staff.

Neilson thought that the market had lost sight of TVB’s strong competitive advantage. The number one television station would receive a disproportionate share of advertising revenue. There was a growth kicker: TVB’s signal could easily be picked up across the border in China, where 60 million potential viewers could potentially see TVB’s shows in addition to Hong Kong’s 5 million. And TVB had an excellent library of Cantonese language dramas. It turned out to be an excellent idea. TVB’s share price rose 6x over the subsequent two years.

As the mid-1990s approached, Neilson became more cautious. He felt that emerging markets had been “a gift from heaven” but that there were few stones left to turn over after a huge re-rating in both Asia and Latin America. In his own words: “the game is almost over”.

“Buying something when it is unfashionable is the key. Now everyone is talking Mexico and everyone owns it; how can you make money when everyone owns it?”

He felt that people weren’t questioning the ideas of the herd. For example, he was astounded by the prices in Hong Kong’s over-priced property market. Most people were delusional in thinking that the Hong Kong property boom would never end.

By 1995, Neilson turned significantly more cautious. He felt that many of these markets had a huge risk of a de-rating. Singapore derated in the mid-1980s. And he felt Japan would derate as well as it had stopped being a high growth economy.

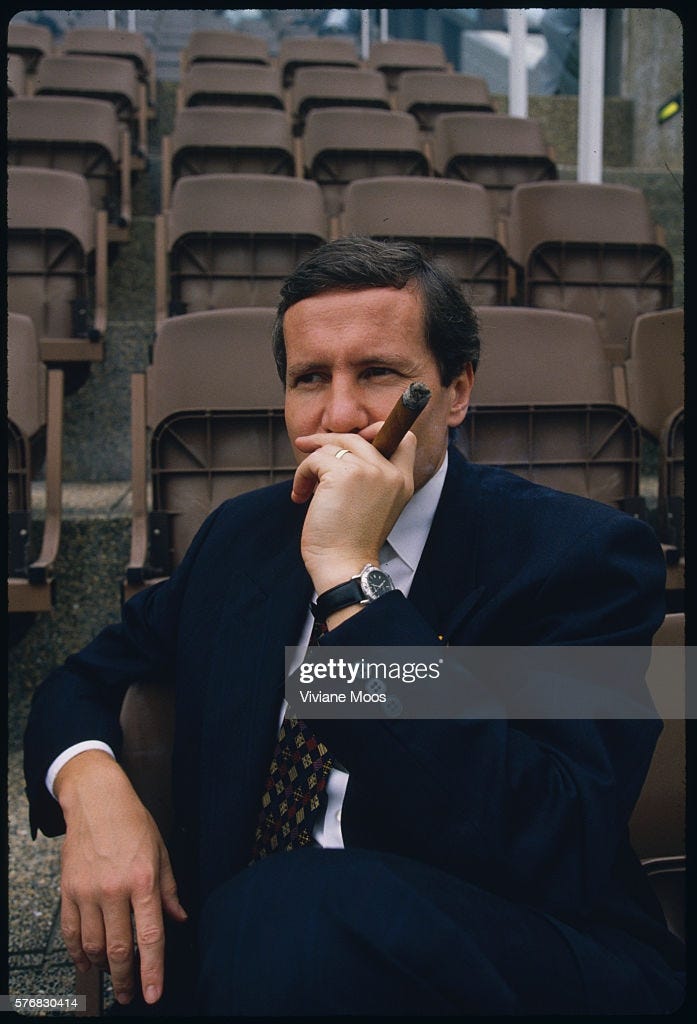

11. Marc Faber

Faber had always been controversial. He was a ski racer growing up in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. He decided to move to Asia after a business trip, visiting Pattaya in Thailand, where he was charmed by local ladies and wanted to stay. Unusual for the fund industry, he wore a ponytail and felt more at home in Hong Kong nightclubs than attending serious investment conferences.

A South China Morning Post poll once asked public figures whether they had ever taken cannabis. Most people refused to answer the question. Faber, on the other hand, was more straightforward and told the reporter:

“Naturally I have smoked a lot of marijuana, but for breakfast I prefer omelette of Balinese mushrooms.”

But despite Faber’s public image, he was more serious than he let on. He received a PhD in economics from the University of Zurich and had a superb library of first edition books on economics and stock market cycles. The more intelligent professionals around Hong Kong saw through his public persona and had a lot of respect for him. His “Gloom, Boom & Doom Report” remains a must reading for any Asia focused institutional investor to this day.

Faber leaned bearish. He played up this image of being an eternal pessimist, helping him gain publicity but also criticism for more bullish individuals. Back in 1987, he wrote:

“No-one likes a party spoiler, and as long as the stock-market orgy goes on the pessimists are shunned almost as badly as AIDS carriers”.

What few people realised is that many of Faber’s long-term calls had also been spectacular. He invested early in Latin America, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. He bought Vietnamese debt at 12 cents on the dollar just before it rose to 70. He bought shares in Korea in 1978, well before foreigners were officially allowed to do so - by bringing in cash into the country in a suitcase on his flight over to Seoul. He also bought Taiwanese stocks in 1980 and waited until the market went vertical in 1985-1990.

Investors accuse him of a major flaw: getting out too early. In 1992, Faber wrote a report called the Life Cycle of Emerging Markets, analysing the investor psychology of each market phase:

He said that he likes to invest in phase zero, which is characterised by long-lasting economic stagnation, flat or falling per capita income, little capital investment, unstable political and social conditions, depressed profits and no FDI or portfolio investment. Faber tries to exit in phase two when large inflows of foreign funds propel the market to overvaluation, hotels are full of foreign portfolio managers, new hotels are under construction, thick research reports are published by brokers and new country funds are launched.

He admits that he tends to get out prematurely and short markets before they peak. A competitor criticised Faber for that reason:

“Why does he do it? It’s as if he can’t bear having anyone else on the beach. As soon as the market is discovered, he picks up his ball and doesn’t want to play.”

Faber defended his market manoeuvres by saying that phase three tends to be a high-risk zone. While in phase two almost all stocks rise, in phase three, the advance becomes much more narrow and breadth deteriorates. The highs reached during phase three may not be exceeded for five or fifteen years or more. So it’s best to start selling a little bit before the market index actually peaks.

One of Faber’s key ideas is “The Paradox of Inflation”: that hyper-inflation tends to produce the greatest bargains. He took the example of the Philippines in 1985 when the Commercial Stock Index had fallen 76% in US Dollar terms. Meanwhile, the Mining Index had fallen by 94% and the Oil Index had fallen by 97%. The entire stock market capitalisation of the Philippines was only US$500 million. Philippine Long Distance Telephone was selling at less than 1.7x earnings. You don’t get such bargains in stable environments. In the same way, The Weiman hyperinflation provided the best buying opportunity for German shares in the 20th century.

By 1995, Faber felt that public markets were fully valued. He was “extremely wary” of the major world equity markets on the grounds of not just valuation, but also the time elapsed, cycle theory, a high proportion of assets now held in equities and leverage of the key players. He felt that a turning point had been characterised by a rolling top in Japan, Korea and Taiwan in 1990 and that all markets would be affected.

In addition, he pointed out that there had been a stampede into emerging markets:

“During the mania, the less people know about an investment theme, the more enthusiastically they tend to endorse the idea… during a mania, the less investors know, the more credulous they are.”

How did he deal with an overvalued market? Faber had decided to turn to private investments. By the mid-1990s, he had become a distributor of Grolsch beer in Hong Kong (“It didn’t give me a headache the next day, so I thought this is a good product!”). He also invested in a hotel project in Da Nang, Vietnam as well as in New Zealand apartment buildings. Other than that, Dr Doom remained cautious.

12. Richard Lawrence

Richard Lawrence had just started out as a fund manager in the early 1990s. An American, Lawrence studied economics at Brown University and then spent two years working as a financial analyst in Venezuela and later New York. He moved to Hong Kong in 1985, becoming a founding employee in FP Special Assets, which was set up to invest in undervalued publicly-listed equities, real estate or venture capital throughout the Asia Pacific.

Lawrence’s value investing roots are clear. When describing his strategy, he cited Benjamin Graham, John Neff, Warren Buffett, Peter Lynch and the other great value investors of the previous decades. Like them, Lawrence wanted to buy good companies at low prices.

His own company Overlook Investments was set up in 1993, renting a small office from Marc Faber who was the first outside investor in his fund. The fund’s prospectus detailed some of the characteristics that Lawrence was looking for: superior long-term growth in EPS, a proven track record of self-financing its growth, strong free cash flows, high return on equity, a strong balance sheet etc. He liked stocks that traded at less than half of their long-term growth rate or less than half of their sustainable ROE.

Lawrence was diligent from the very beginning of Overlook Investments. He used paper sources only, avoiding screens. He spent a lot of time on financial modelling and cash flow projections. He would do 150-200 company visits each year and had a stock turnover of only ~20%.

In 1995, Lawrence had most of his portfolio in Korea, followed by Hong Kong and Thailand. He had no interest or views on the macroeconomic conditions in each of these markets, he just happened to find inexpensive stocks in these countries. So he was unprepared for any macroeconomic shocks, preferring instead “to focus on the fundamentals”.

For example, in 1993 he invested in Shin Poong Paper Manufacturing Company in South Korea, a producer of white cardboard paper used for packaging consumer products. What attracted Lawrence to Shin Poong was its 20% market share, positive feedback from customers, exposure to the fast-growing Guangdong market, improving competitiveness from the rising Japanese Yen, a strong balance sheet, conservative depreciation policy and a new capacity expansion of 40%. The stock traded at 5.3x trailing EPS and had grown at a rate of 23% since 1984.

The rest of his portfolio had similar types of inexpensive, compounder-type stocks that most had never heard of. Song Woun Industries, Winton Holdings, Pacific Insurance and Samsung Radiator. Most of them at P/E ratios of 5-8x.

13. Cheah Cheng Hye

Cheah’s speciality was Hong Kong small caps. Many fund managers at the time treated Hong Kong small caps with suspicion, but Cheah went against the grain and argued that there were bargains among the rubbish. His local knowledge and connections helped him and his partners separate the wheat from the chaff.

Cheah grew up in Malaysia but spent most of his career as a journalist in Hong Kong. After a stint from the Asian Wall Street Journal, he joined Morgan Greenfell to set up their Hong Kong Research department in 1989. After a few years, he met a person called V-Nee Yeh and they formed their own firm in 1993 called “Value Partners”. Initial assets were just US$3 million but grew quickly to US$70 million within a year and a half.

What is Cheah’s strategy? He liked to buy cheap stocks. Bombed out IPOs was a favourite area to search for new ideas. Another area of opportunity was cyclical turnaround stories where the shares traded below book value, had no institutional following and he thought an immediate earnings rebound was coming.

He shunned any contact with brokers, preferring to rely on annual reports and Value Partner’s own network of contacts throughout Hong Kong. Low P/E, high dividend yield, low price-book and a decent return on equity were all factors he took into account.

By the end of 1994, Cheah had 80% of his portfolio in Hong Kong stocks. The average P/E was 7.9x, dividend yield 5.9%, P/B of 1.6x and ROE 23%.

One of Cheah’s favourite stocks was taxi financing company Winton Holdings. Why? Because as a specialist lender he thought they would be able to appraise the creditworthiness of borrowers better than others. They borrowed at 1-2% over HIBOR and lent at a floating rate around 22-23%. The default rate had historically been just around 0.5%. The market seems to have considered Winton’s margins to be unsustainable but Cheah felt he had done his research and that the business would continue to compound capital at a rapid rate.

14. Charles Fowler

Among the people featured in the book, Charles Fowler was the only fund manager who had never lived in Asia.

A stock picker at heart, Fowler loved to visit small companies, arguing that they were less researched. And if they were researched, it was usually by the most junior analyst who failed to pick up significant points at the company level.

Fowler tried to take 6-18 month views on a market and is looking for situations where the market was getting something wrong. He admitted that he didn’t have many ideas each year, so when he did, he backed them heavily.

His investment strategy was based on a long-term concept and blue-sky potential, together with the likelihood of positive surprises. In other words, he was looking for blue chips before they became blue chips.

Fowler’s track record was enviable. He bought Philippine stocks in 1986 in the last days of the Marcos regime. Had he been really brave, he would have bought prior to the election. But he moved after they had shot up 50% and still made a killing on his investments. For example, he started buying Philippine Long Distance Telephone at PHP 1.5/share. By the mid-1990s, the stock had reached PHP 70.

A little later in 1986, he bought a large stake in Taiwan ahead of the market’s upwards explosion. At the time, the index was just 1,000. By 1990 it had risen to 12,000. As the savvy investor that Fowler was, he chickened out at 7-8,000 for a five-fold profit for the fund. He then watched on the sidelines as the market crashed down to 2,500.

Hotel investments in Southeast Asia also turned out well. He bought Jakarta International Hotels in 1988 and quadrupled his money. He was early into Sri Lanka, investing in Asian Hotels.

15. Angus Tulloch

Based in Scotland’s Edinburgh, Angus Tulloch ran Stewart Ivory’s emerging markets team. He graduated from Cambridge with a degree in economics and history. After a few jobs in accounting, he joined Cazenove in 1980, spent three years in Hong Kong before moving back to the UK.

One of Tulloch’s key tenets is that much of investment theory had developed in the United States where real estate is much more important as a component of the business. Westerners tend to argue that the value of a company is the sum of its future cash flows. But in Asia, entrepreneurs care a lot more about building asset values. When choosing a site for a brewery, for example, an entrepreneur may pick a location with long-term potential for an extraordinary gain in land prices. So Tulloch learnt to take asset values into account and would track the growth in net asset values and bet on entrepreneurs who were adept at building value, be it through cash flows or clever investments.

Over the five years to 1994, the Stewart Ivory New Pacific Fund had achieved a compound annual growth rate of 23% against 13% for the MSCI Pacific Index.

One of the stocks that Tulloch liked the most was Singapore’s Trans Island Bus Service (now part of Temasek-owned SMRT). He bought it when its P/E was half that of the market. He appreciated that buses were depreciated over just eight years compared to fifteen in the UK.

He also liked Malaysia’s Perlis Plantations, with its NAV growth of 17% per year. Its key interests included flour-milling and sugar-refining, whose cash flows were used to buy low yielding but potentially rewarding assets (hotels, plantations and property).

16. Anthony Cragg

Cragg was one of the few successful American fund managers who invested in Asia at the time. After finishing university in Oxford, he spent three years teaching English in Nagoya. In 1980 he joined Gartmore, first in London and then in Hong Kong, before setting up the Tokyo office in 1984. After a short stint back in London, he moved to Milwaukee, United States in 1993.

While he described himself as a value investor, he felt that American analysts were unnecessarily focusing on precise calculations. In an Asian context, whether a company trades at 12x or 15x earnings often doesn’t matter much. In a fast-growing business, one year’s worth of growth could easily equalise the multiples.

In the book, Cragg was described as a safe pair of hands. Experience with impressions of thousands of company visits over the years helped him recognise patterns.

On the other hand, volatility in the region could be scary even to seasoned investors. Price movements often mean nothing. A share price could have sold down due to a clumsy foreign seller, a silly domestic rumour or a weak market that day.

“You can’t afford to worry, you just buy more and average down, but this volatility can be quite unsettling for a US-trained investor.”

Cragg was consistently cynical on prospects in China, swimming against a tide of enthusiasm. He warned that entrepreneurs were adept at supplying the stocks which the market wants, playing on the enthusiasm of naive new investors.

“China was such a strong drug, it was like honey to bees, a lot of companies blew up that angle.”

The Aftermath

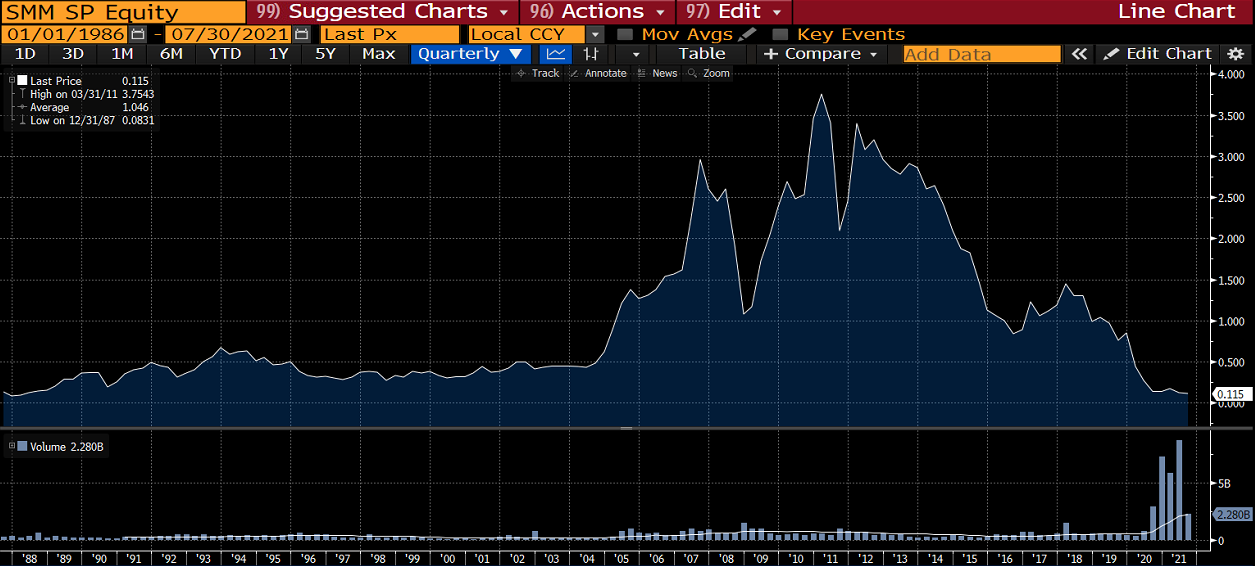

Roughly 2 years after the book was written, Southeast Asian stock markets began to wobble. It quickly turned into a carnage - especially among small-caps and the more illiquid markets such as Indonesia and the Philippines. While the stocks in some of these markets were cheap on their own, emerging market currencies went into a free-fall after developed market liquidity tightened while carry trade flows reversed.

Current account deficits in markets such as Thailand, South Korea and Indonesia led to a vicious circle of falling exchange rates, higher debt burdens, central banks hiking interest rates, forced deleveraging and complete and in the end - total panic. The Indonesian market fell over 90% in US Dollar terms.

So what happened with each of the personalities featured in Claire Barnes’s book?

Fidelity’s talented stock picker Peter Phillips (1) stayed with Fidelity for many years, moving to Japan with the firm in 2001. He later set up Frontier Asia Capital in Hong Kong together with Jeff Kung, his colleague at Fidelity. Fidelity’s Emerging Asia Fund dropped roughly 50% in the crisis but went on to perform very well in the subsequent decades.

Adrian Cantwell (2) of Global Asset Management won the South China Morning Post’s Fund Manager of the Year 1995 award. But he ceased to be in the press following the Asian Financial Crisis. It appears that he moved back to the UK working as a senior investment manager at Thring Townsend, later running his own consultancy firm Cantwell Consultancy. And now, it looks like he is based in Vancouver as the CEO of Shield Hedge Fund Management.

David Lui (3) continued working for Schroders after the crisis. He helped Schroders set up a joint venture with Bank of Communications in 2005 and moved to Shanghai where he started his new career. It seems to have worked out very well for him.

Perma-bull Colin Armstrong (4) was sacked from Jardine Fleming in 1996. He had “engaged in the late allocation of deals after changes in the price of the instruments traded had occurred”, making significant profits for himself in the process. Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission revoked his registrations as an investment adviser, securities dealer and commodities trading adviser. Colin Armstrong was forced to pay back US$20 million in restitution payments to investors. Jardine Fleming itself was acquired by JP Morgan in 2000. It seems that Armstrong never managed to make a come-back.

William Kaye (5) stayed in Hong Kong. His Pacific Alliance Group is still in business after 30 years. He is now a senior managing director of the firm, overseeing portfolio and direct investments. But on his Linkedin profile, Bill says that:

“I still have a passion for investing but it's no longer about the $$$. I like the challenges involved in my work and the fact I continue to learn new things every day.”

Bill became interested in the gold market in 2008 and described his views on the metal in a 2015 interview with Real Vision TV.

Investor genius Edward Kong’s (6) EK Investments survived the crisis and Kong stayed on as a responsible officer for the firm until 2013. There are no traces of him on either Bloomberg or in any other English news publications.

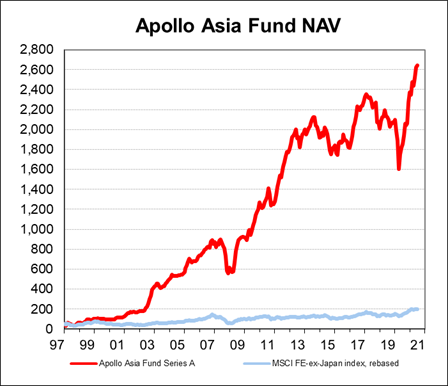

David Crichton-Watt (7) moved to Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia. He helped author Claire Barnes set up the Apollo Asia Fund and also the Phoenix Gold Fund, the Panah Fund and the Alwaha Fund under AIMS Asset Management. Although the funds remain small at a few hundred million US Dollars, he seems to have done well for himself given that he recently purchased a Georgian house in Herefordshire, UK. But his Linkedin profile suggests that he still lives in Kuala Lumpur and continues to manage money.

Peter Everington (8) continued to serve as an executive director of Regent Pacific until 2002. Regent Pacific acquired an Internet investment group in 2000 and expressed bullishness about the Internet sector:

“We have been an early investor in a number of Asian internet companies and have built up an excellent portfolio."

Since then, Regent Pacific changed its name to Interman. It now seems to have zero assets under management. Everington was last listed as a Vice Chairman of Koreaonline Ltd in Seoul but it’s unclear whether this company still exists. He is listed as a trustee for a charity in England, suggesting that he has moved back to the UK.

Michael Sofaer (9) still runs his own firm Sofaer Capital out of London, UK. According to this Institutional Investor article, Sofaer’s flagship SCI Asian Hedge Fund returned 11% CAGR in the decade to 2002 compared to just 3% the MSCI all countries Far East ex-Japan Index. According to the article, Sofaer hedged his portfolios and thereby protected his capital during the crisis:

“Sofaer saw the crash coming and shorted the Thai baht as well as the Indonesian rupiah, the South Korean won and the Malaysian ringgit”

Kerr Neilson (10) still serves as the CEO of Platinum Asset Management and remains a portfolio manager for the global mandates. The company went public in 2007 and has become a household name in Australia and across the world.

Marc Faber (11) remained a major media personality, continued to write his Gloom Boom & Doom Report and is also involved in a number of funds, including Leopard Capital’s Cambodia Fund and the AFC Asia Frontier Fund. His book Tomorrow’s Gold in 2002 became a global best-seller. Racist remarks in 2017 caused him to be banned from major media platforms but he continues to do interviews with smaller platforms such as ICICI Direct and Wall Street Silver.

Richard Lawrence (12) still runs Overlook Investments, which has become a very successful organisation with US$7.6 billion under management. Over the past year, he has expressed bullishness about Uni-President Enterprises, China Yangtze Power, Alibaba and Galaxy Entertainment.

Cheah Cheng Hye’s (13) Value Partners became a highly successful asset management firm in Hong Kong and went public in 2007. It’s widely regarded as a Hong Kong success story, though the company’s investments have become more conservative over time. His partner V-Nee Yeh later became a member of the Executive Council of the Hong Kong government.

Charles Fowler (14) at John Govett became Chairman of MG Capital in 2002. Lately, he has become involved in charities and non-profit organisations such as the Human Value Foundation and UK Values Alliance.

Angus Tulloch (15) stayed with Stewart Investments and later Stewart Ivory where he served as a co-manager of the Asia Pacific Fund as well as two other Asia related funds with AUM of around US$400 million. He retired in 2017.

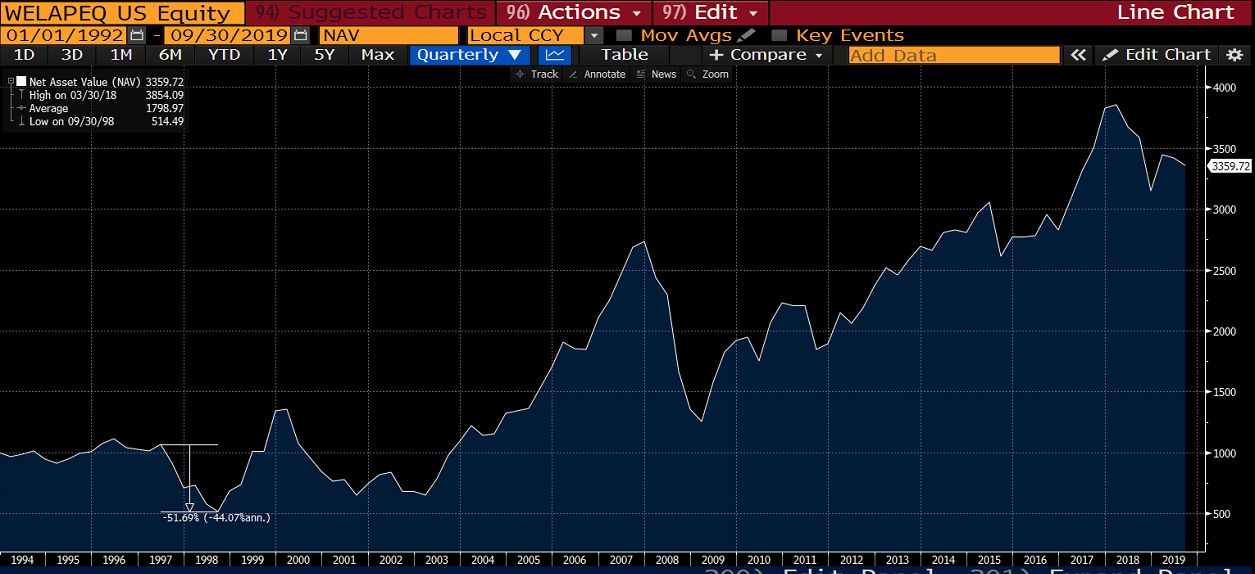

Anthony Cragg (16) at Strong/Corneliuson stayed with Strong Capital Management until it was acquired by Wells Capital Management. Since 2018, Cragg is listed as a “former adviser”, suggesting that he may have started to retire. The Asia Pacific Fund had a drawdown of around 50% through the Asian Financial Crisis but remained small, despite spectacular performance in the subsequent decades.

The author of the book Claire Barnes went into fund management herself. She set up Apollo Asia Fund through the help of David Watt close to the bottom of the crisis in 1997 and has compounded at an annual rate of 19% since inception. According to her latest quarterly letter, she now has a large proportion of her fund in Vietnamese equities.

Final words

While the Asian Financial Crisis was a traumatic experience for most fund managers who lived through it, it seems that most of the investors featured in Claire Barnes book managed to survive the crisis. Many of them had drawdowns of over 50%, but ultimately managed to persevere.

The individuals working for large organisations such as Fidelity and Schroders did well and moved on to managing other funds within their companies.

The investors who emphasised value did better than others. I am thinking primarily of Richard Lawrence, Cheah Cheng Hye and David Watt.

Perma-bull Colin Armstrong was accused of fraud and never managed to make a comeback. The lesson here may be to always be honest in your dealings.

One last comment is about the stocks featured in the book. Some of the true blue chips mentioned by the investment prophets such as Cathay Pacific, TVB and South China Morning Post performed well in the short run. But today, they are shadows of their former selves.

The future is unpredictable, so the best we can do is to keep learning, try to survive and hopefully live to see another day.

If you would like to support me and get 20x high-quality deep-dives per year, thematic reports and other reports, try out the Asian Century Stocks subscription service - for the price of a few weekly cappuccinos.

I think you are confusing Asia Frontier Capital (Thomas Hugger) with Frontier Asia Capital (Peter Phillips). The two are unrelated. Angus Tulloch retired in 2017.