Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

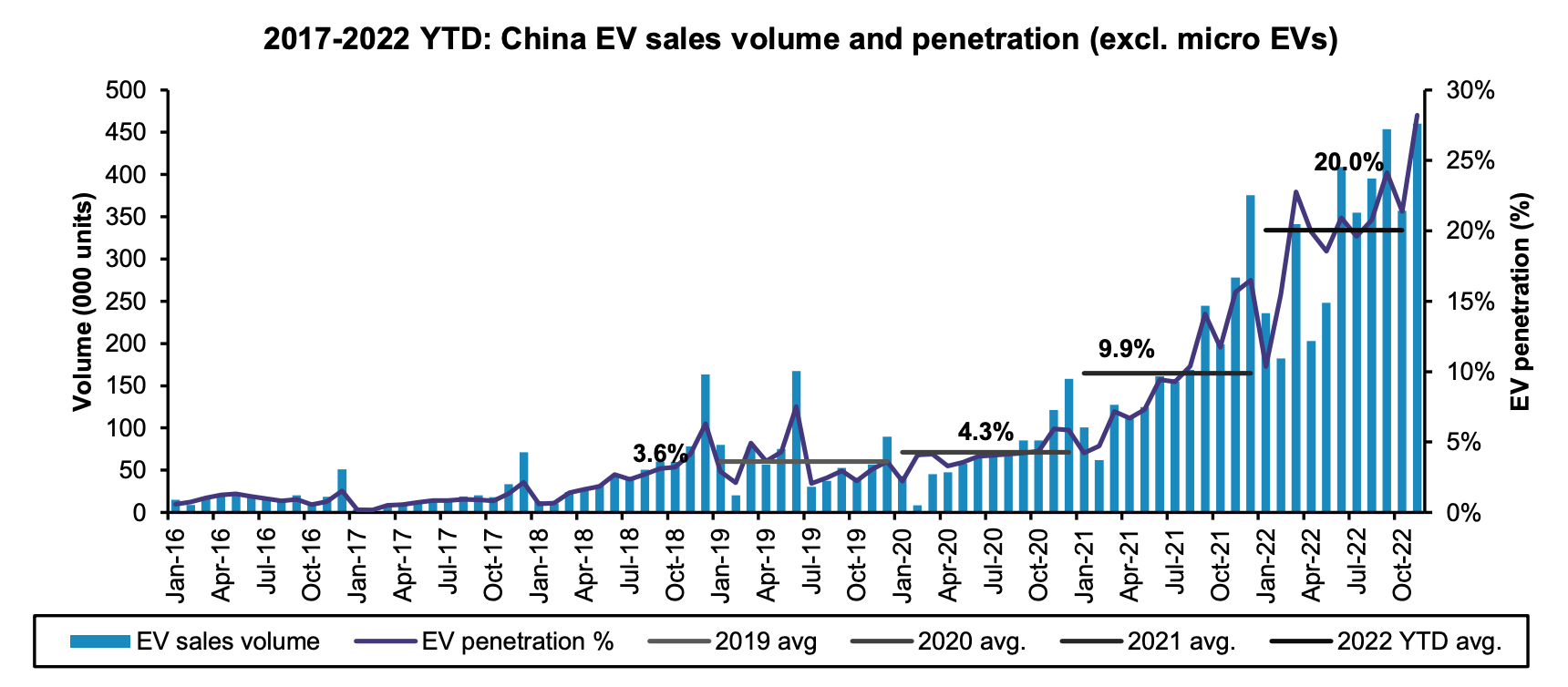

China’s electric vehicle (EV) market has been on a tear:

But much of this success has been driven by subsidies. And those subsidies cannot last forever.

The big question for 2023 will be whether the market will be impacted by the phase-out of financial subsidies that will occur by the end of the year.

1. China’s initial EV subsidy spark

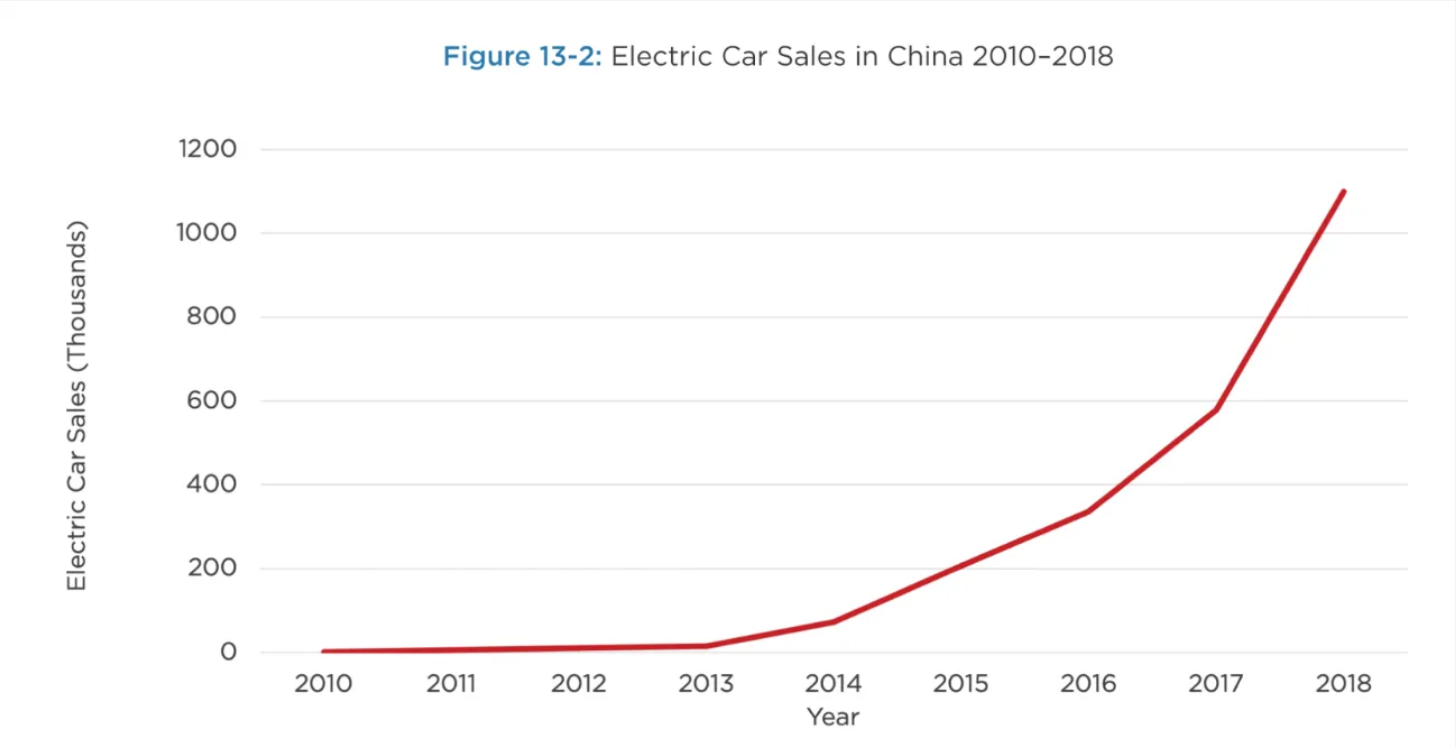

The first step in the development of China’s EV market came with the 2009 pilot program Thousands of Vehicles, Tens of Cities.

The program aimed to roll out at least 1,000 EVs in ten cities over three years to test their commercial viability. The government introduced subsidies based on fuel savings. A battery-passenger EV in the pilot program enjoyed a financial subsidy of CNY 60,000 per vehicle.

But the real spark of China’s EV industry came in 2013-2014 when the subsidies were expanded to 39 cities. And this time around, the subsidy levels increased significantly across the following:

- Central government subsidies: A battery vehicle with mileage of 150-250km received CNY 50,000 in central government subsidies

- Local government subsidies: up to 100% of the central government subsidy could added on top

- Purchase tax exemption: China’s 10% vehicle registration tax was waived for all electric vehicles

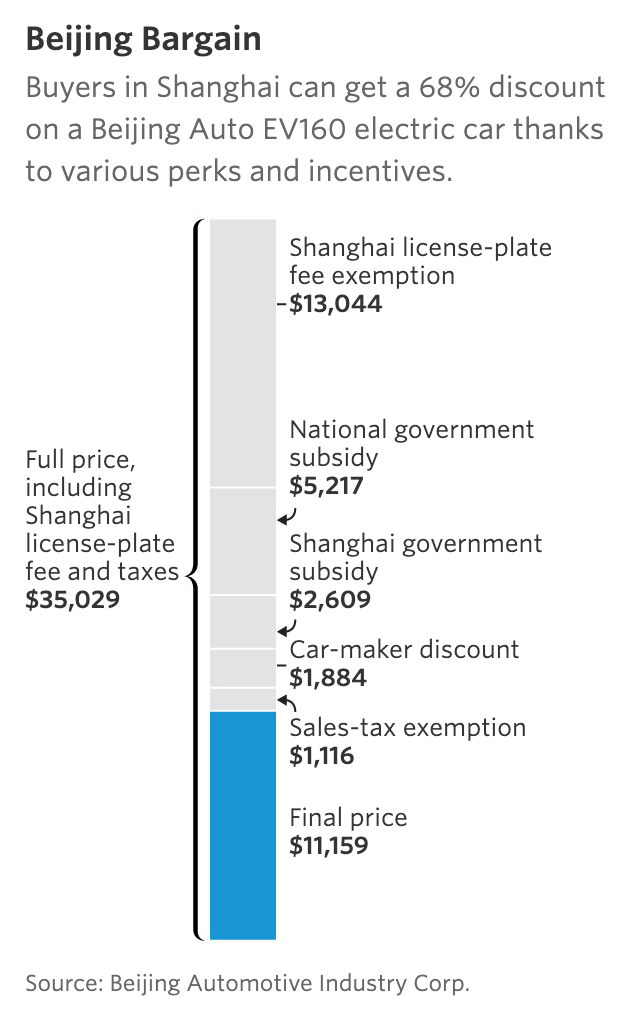

Adding up these financial subsidies, a buyer in those 39 cities could get more than half of the price of his or her EV subsidised by the government. Nothing to sneer at.

Then came the license plate benefits. In cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Chengdu, you started getting traffic control and license plate benefits by purchasing an EV. In some cities, owning an EV enabled you to drive any day of the week. In other cities, buying an EV enabled you to get a scarce license plate for free.

Here’s one example of how the above subsidies could add up. In the case of a Shanghai-based purchaser of a Beijing Auto EV160 vehicle, by applying relevant subsidies, an EV with a theoretical price of US$35,029 ended up costing just US$11,159 - a discount of almost 70%.

There were also subsidies given to the car makers. The central government contributed significantly to EV-related R&D projects. They reduced the import duties for EV-related parts and equipment. And they also subsidised the installation of EV charging facilities.

As you can guess, the impact on the Chinese EV market was legendary. The EV penetration rate rose from almost nothing in 2013 to over a million vehicles by 2018.

2. The gradual phase-out of subsidies

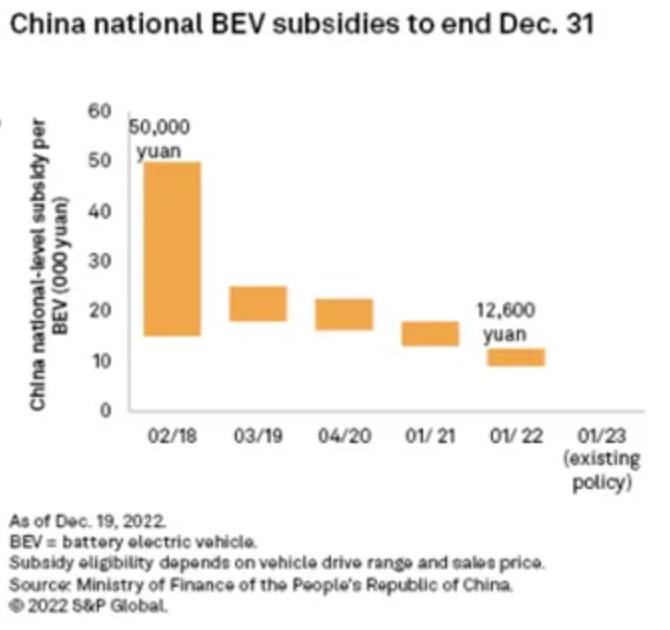

But we’re now starting to see the subsidies being phased out.

From 2017, the local government EV subsidies were reduced to no more than 50% of what the central government offered. And from 2018, the central government itself reduced its financial subsidy to 80%, 60%, 40% and, by the end of 2022, to 0% of the original amount.

The 10% purchase tax exemption will remain until the end of 2023. But after that, Chinese EV buyers will be left without any financial subsidies whatsoever.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that the EV market will crash. Traffic control and license plate provisions still remain. In 2019, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) ordered local governments to remove EV license plate restrictions, allowing anyone who wants to purchase an EV to do so.

Such traffic control and license plate benefits include being able to drive your EV all days of the week, being able to bypass license plate lotteries or obtaining a license plate for free.

License plate benefits can be significant. In Beijing, for example, there have been 3 million people on the waiting list, and only 100,000 license plates were handed out each year.

The Chinese government also pushed for ride-hailing fleets to become electric. For example, from 2020 onwards, Shenzhen required that 100% of its ride-hailing vehicles be electric. In 2021, Guangzhou, Zhengzhou, Wuhan and Xi’an also introduced similar laws.

The final chapter in China’s EV subsidy story is about so-called “NEV credits”. Such credits are modelled after California’s zero-emission vehicles program, which tries to use market-based pricing to incentivise EV production. In detail:

- If an automaker produces a traditional gasoline engine vehicle, he will need to offset that vehicle through an “NEV credit”.

- The automaker can either obtain NEV credits by producing electric vehicles or by buying NEV credits from another automaker.

- Those NEV credits cannot be carried forward to the next year. That means that the industry’s aggregate NEV production has to hit the target each year, or else certain automakers will have to pay financial penalties.

In my view, while the 2013 financial subsidies helped pushed the demand for electric vehicles, these NEV credits will instead push new supply of them.

So to summarise, we’re now at an important crossroad, with the central government and local government EV subsidies reduced to zero on 31 December 2022. And the 10% purchase tax waiver for EVs will be removed by the end of this year as well.

The big question now is whether China’s EV market has reached “escape velocity”. Or is it simply a mirage built on unsustainable government subsidies?

3. Implications of China’s new EV policies

“It’s the state’s support which is really driving the attention and demand for EVs… I just have a slight skepticism that in the future, if these subsidies are gone, whether the consumers would still want to buy EVs at the market price.”

- Hiroji Onishi, Senior Manager at Toyota China

For the Chinese EV market to become self-sustaining, consumers will need to find electric vehicles a better value proposition than their ICE equivalents. EVs need to offer a combination of better convenience and lower prices.

- Convenience: Whether EVs are convenient is debatable. While charging your EV at home saves you a trip to the gas station, few Chinese have access to EV charging points. The driving range remains far lower than you’d get with an ICE. If you need to drive longer distances, expect to queue up for a charging station and wait a long time for the car to become fully charged. The safety aspect is also worth mentioning, as batteries can and occasionally do self-combust.

- Low price: The price of a battery needs to come down significantly below the price of an internal combustion engine. EV batteries are often replaced after 8-10 years, whereas a gasoline engine easily lasts twice as long. Electricity is cheaper than gasoline, but it’s still hard to make the numbers work. Today, a typical EV battery costs about US$10,000, while an engine costs no more than US$3,000. It will take many years of 5% per year energy density improvements, or a breakthrough in solid-state battery technology, for the calculus to change significantly.

In my view, the above calculus does not favour electric vehicles.

The reality is this: the main draw of buying an electric vehicle in China has been the massive financial subsidies and the license plates benefits. We’re unlikely to see a typical S-curve mass adoption curves as we’ve had with smartphones, microwaves and colour televisions, for example, in the past. Hedge fund manager Jim Chanos seems to agree that EVs does not the fit the profile of a typical S-curve:

@garyblack00 EV’s, out for ten years now, are the slowest adopted “disruptive” consumer technology in modern memory. Less than 3% in a decade. Despite massive subsidies.

— Diogenes (@WallStCynic) 7:24 PM ∙ Jul 10, 2020

In the near term, expect a drop in EV sales as the financial subsidies are phased out. As I’ve written in the past, when EV subsidies were removed in Hong Kong, Denmark and the state of Georgia, EV sales dropped 80-90%.

Traffic control and vehicle ownership control exemptions will remain in many cities. That will ensure certain demand. The only question is, how long will such restrictions remain?

Another question is how China’s new NEV credit system will affect the economics of building an electric vehicle. Here is how I foresee the market developing:

- Pure-play EV makers will benefit from the NEV credits they obtain from producing vehicles at the expense of traditional automakers.

- As long as the value of an NEV credit is positive, car companies will be willing to sell EVs at a loss since they’ll make up for that loss through sales of NEV credits.

- The value of the NEV credits will incentivise automakers to build their EVs as cheaply as possible to maximise the NEV credit value/cost ratio.

In my view, at the end of the day, the auto industry is competitive. Without a moat such as a Tesla-style charging network, it will be difficult to achieve superior returns on capital. It doesn’t matter much whether regulation pushes the consumer in one direction or another.

4. Evidence of an unbalanced market

Several on-the-ground facts make it clear that EVs are not going to become mainstream anytime soon:

- In China, over half of auto sales are for vehicles below CNY 150,000. But the high battery costs of building an EV make it almost impossible to sell them below that level. Battery prices either have to fall, or the government has to intervene somehow.

- Almost all of China’s urban population live in apartments, and only a portion of those individuals have access to underground parking garages suitable for EV charging stations. Even fewer have the wiring set up for an EV charger, and even fewer would install such chargers if the state grid did not subsidise installations.

Another concerning trend is the auto graveyards that have popped up across China over the past few years. A source at an automaker suggested that roughly 70% of EV buyers were not individuals but corporations. So the main driver of China’s EV market is companies, such as the major ride-hailing companies.

Many cities require their ride-hailing fleets to be electric. And the ride-hailing companies tend to have automakers behind them. One trend we’ve seen in the past few years is automakers buying minority stakes in ride-hailing companies, which have then purchased the vehicles produced by the automaker itself.

That’s problematic because ride-hailing companies are now experiencing significant losses. But the charade has continued in many places, with car manufacturers enjoying subsidies and being able to reach their financial targets through such schemes.

Since lower-end EVs are not particularly convenient, some ride-hailing companies have left their vehicles abandoned in auto graveyards until the subsidies have been received. And there are reports of vicious depreciation of the lower-end EVs typically used by ride-hailing companies. Since they’re not worth much, they’re often sold for scrap after a few years.

It’s hard to say how common such auto graveyards are. But if the 70% number is accurate, then at least we know that EV sales are probably driven by regulation rather than real, underlying demand.

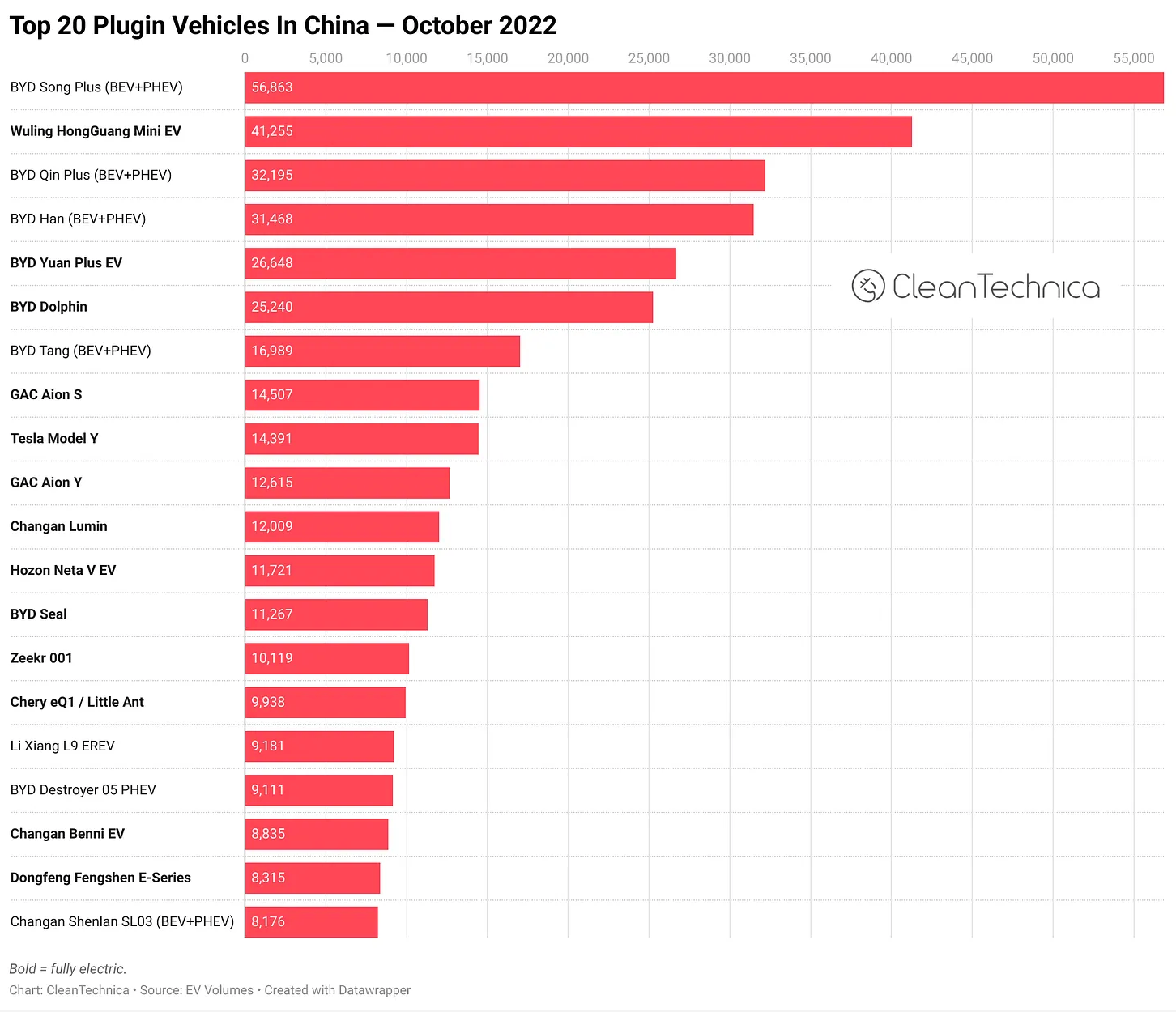

Another piece of evidence that speaks against EVs is that most of the most popular EVs are ultra-cheap, including so-called “Mini EVs”.

For example, the ultra-popular Wuling Hongguang Mini EV costs no more than CNY 40,000. It’s unclear how automaker SAIC can make money on such vehicles if it wasn’t for the NEV credits they obtain from them.

While NEV credits were worth around CNY 2,000 each in 2020 and 2021, income from selling NEV credits has declined. Many automakers seem to think that it’s better to produce the required number of EVs rather than buy credits from somebody else or pay the penalties.

Again, it looks like much of what we see in China’s auto market today is driven by regulation rather than real, underlying demand.

The remaining part of this post will be exclusively available to paid subscribers. Click below to subscribe and gain access to the full post: