20 rules for investing in Vietnam

Andy Ho's guide to investing in the "Wild East". Estimated reading time: 24 minutes.

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. From time to time, I may have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Last year, Vietnam investor Andy Ho of VinaCapital published a book called Crossing the Street. I was excited to see it because books about Vietnamese equities are few and far between.

First some background about Andy. His family was originally from Vietnam but moved to the United States after the war. He started his career at Ernst & Young, then ended up taking an MBA at MIT and working for Dell for a few years.

After a vacation to Vietnam in 2003, he fell in love with the country. So much so that he and his wife decided to live there for a few years. Now, almost two decades later, he is still in the country and enjoying every moment of it.

Andy's current position is Chief Investment Officer of VinaCapital, one of Vietnam’s largest investment managers with roughly US$4 billion in assets under management. The company manages several funds, including the London-listed closed-end fund VinaCapital Vietnam Opportunity Fund (VOF LN).

I recommend Kalani Scarrott’s interview with Andy on the Compounding Curiosity podcast. It provides the background story of how he ended up in Vietnam and the challenges he encountered along the way.

The case for investing in Vietnam

Andy Ho calls Vietnam “the last significant opportunity for investors in Southeast Asia”.

Vietnam is following the East Asian playbook of manufacturing export-led growth - just like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China before it.

After the Vietnam war ended in 1975, formerly capitalist South Vietnam was taken over by the Communist Party of Vietnam and the country was unified.

The first measure taken by the communists was to nationalise and centralise the entire economy. Around 800,000 Vietnamese fled the country after the war, including Andy’s family.

It only took three years before war broke out again - this time against Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge, led by dictator Pol Pot. That war continued until the late 1980s. So Vietnam was almost in a constant state of war for almost half a century.

By the late 1980s, the country was in disarray. And it was becoming clear that the planned economy was not functioning properly.

The Communist Party introduced a new reform program called Doi Moi to create a “socialist-oriented market economy”. One of the first Doi Moi policies was to permit foreign investment to modernise the economy.

Today, Vietnam is buzzing with activity. The country has more free trade agreements than any other country in Southeast Asia. It’s become the default destination for companies wanting to diversify their manufacturing supply chains out of China. Vietnam is a perfect choice for manufacturing - in close proximity to key component suppliers in Asia and along the key trade route between Asia and the West.

Vietnam’s success is most evident in the country’s exports, which have risen the fastest of any country in Southeast Asia.

This export growth is also showing up in the country’s urbanisation, with young Vietnamese moving to factories to improve their livelihoods. Vietnam’s urbanisation rate is still only 38%, compared to China’s 70% and Japan’s 92%.

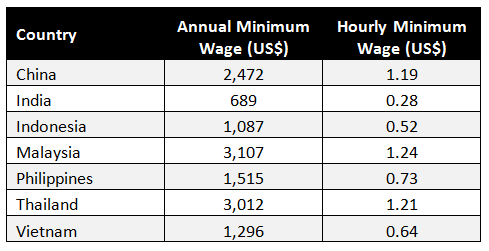

Vietnam’s potential is massive. Its GDP per capita is only US$2,800/year, compared to Thailand’s US$7,200 and China’s US$10,500. Manufacturing wages remain competitive, even against countries with worse infrastructure such as the Philippines and Indonesia.

Out of a total population of 97 million, Vietnam now has a middle class of 30 million people. And it’s rising rapidly. Many of those individuals are starting to buy properties, cars, home appliances, electronics and more.

Imagine the upside potential. The car ownership per 1,000 people in Vietnam is only 25 compared to 173 in China and 816 in the United States. The oil consumption per capita is only 1.9 barrels per year in Vietnam compared to 3.3 in China and 20 in the United States.

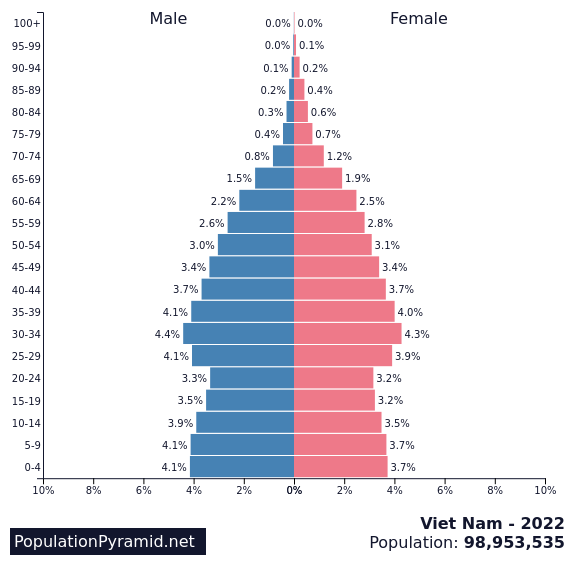

In addition, Vietnam’s demographics are excellent, with two-thirds of the population below 35 years of age. Vietnam’s working-age population is going to grow for another 15-20 years.

The country is also highly educated. Vietnam’s PISA scores are higher than the equivalent scores in the United States, the United Kingdom and even South Korea, even though its GDP per capita is minuscule in comparison.

Vietnam’s stock markets

Most of Vietnam’s blue-chip companies are listed on the Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange (HOSE), in the country’s biggest city Ho Chi Minh City (formerly known as Saigon). There are 416 listed stocks listed on the HOSE, including those of high-profile companies such as Vingroup, Masan Group and Airports Corp of Vietnam.

Then there is the Hanoi Stock Exchange in the capital of Hanoi. It has 348 stocks listed there, many of them from Northern Vietnam.

Finally, there’s the Unlisted Public Company Market (UPCoM), which is actually a part of the Hanoi Stock Exchange. UPCoM is where newly privatised state-owned enterprises list prior to migrating to the Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange.

Vietnam’s aggregate market cap has risen rapidly over the past ten years, driven by earnings growth, higher valuations and privatisations of state-owned enterprises.

There are foreign ownership limits in Vietnam. For many companies, foreigners cannot own more than 49% of the shares and for banks, that number is just 30%.

If the foreign ownership limit has been reached, foreign investors may have to pay a premium to the local share price to get hold of a block of shares from another foreigner. Popular stocks such as FPT Corporation trade at almost permanent premiums to their local share price.

As a foreign investor, getting access to the Vietnamese stock market is difficult. Few international retail brokers offer trading access. And those who do, including Phillip Securities, UOB Kay-Hian and Maybank offer phone trading access only.

So most investors who are serious about investing in Vietnam tend to open a dedicated Vietnamese brokerage account with a local firm such as Saigon Securities.

They can also invest in Vietnam focused ETFs such as the VanEck Vietnam ETF (VNM US) or the Global X MSCI Vietnam ETF (VNAM US). Or a closed-end fund such as VinaCapital’s own Vietnam Opportunity Fund (VOF LN).

The Vietnam Opportunity Fund

The fund that Andy has been closely involved with since he started at VinaCapital in 2007 is the Vietnam Opportunity Fund (VOF). It’s a closed-end fund listed on the London Stock Exchange with the ticker VOF LN.

The fund’s largest holdings are currently the steel producer Hoa Phat Group, real estate developer Khang Dien House, Asia Commercial Bank, Airports Corporation of Vietnam and tech company FPT Corporation.

It’s performed nicely since its inception in 2003, rising over ~8x in pound sterling terms with dividends reinvested, representing a compound annual growth rate of close to 13%.

In the latest fund update, VOF traded at a 19.5% discount to NAV with a management fee of 0.5-1.5% and a performance fee of 12.5%. At that time, 63% of the fund is invested in publicly listed equities and the rest is in private equity or private equity-like situations. You can find the VOF fact sheet here.

Andy’s 20 rules for investing in Vietnam

What I love about the book is the collection of stories about how business is done in real life-Vietnam. Andy is honest about the risks and challenges he and his team encountered along the way. And how they learnt to deal with them.

After reading the book, you come away with a feeling that you’ll probably want a local partner or a local adviser before committing any capital. Plenty of opportunities - but plenty of pitfalls as well.

So here is a short overview of Andy’s 20 key rules for investing in Vietnamese companies, especially from the perspective of a private equity investor.

1. Ensure alignment between management, controlling shareholders and yourself

The first point is straightforward. If management sells a stake in a company to you, he or she has to remain committed to the business. Your interests and theirs have to be aligned.

Andy tells the story of a state-owned fish-processing company that had just been privatised through an IPO. The government remained the controlling shareholder.

When visiting the company’s plant in the Mekong Delta, he realised that half of the inputs (raw fish) came from the fish farmed by the families of the company’s executives. For every piece of raw fish that was processed through the plant - the CEO and the people around him would take a cut.

Other examples included:

A beer company where the distributors were owned by company executives

A food company that sourced raw material from a company owned by a board member

A high-profile company where every purchase order included a 5-20% kickback

A large conglomerate where the chances of employment were higher if the candidate provided undefined “services” to the head of the HR department

These are just some of the stories mentioned in the book.

What can be done to minimise the risk of such situations emerging? First, Andy thinks that it’s important that the management team have a meaningful stake in the business. Second, that the management team is rotated frequently. And finally, that they’re paid fair wages so that they don’t feel forced to game the system to survive.

2. A carrot without a stick is useless

When VOF invests in a company, it tries to include provisions in the deal terms to make sure that management fulfils its commitments. Those commitments are usually related to increasing either revenue, profit and EBITDA.

The specific provisions include

Cash rebate: the sponsor is forced to return some of the principal

Share top-up: VOF receives more shares in the company

Put option: allows VOF to sell the block of shares back to the company with a stated minimum IRR

Drag-along rights: the sponsor gives away a controlling stake which VOF can then sell to a third-party, strategic buyer

If a sponsor over-promises and then consistently misses its target, then VinaCapital might want to get out. A put option might help them achieve this, without any need for activism or a messy divorce.

3. Trust in the management

Can you trust the management to develop a reasonable business plan, execute it and - most importantly - not steal from the company? That’s what Andy refers to as the trust factor.

He mentions the story of a large successful construction company in Vietnam that VOF invested in.

The business was booming and the construction company managed to build a significant backlog of work.

Then suddenly, something weird happened. The company set up subsidiaries that were majority-owned by the board of directors, the management and key allies. And these subsidiaries started competing with the ListCo for business.

In 2015, the net profit of those subsidiaries was only 11% of that of the ListCo. By 2019, the number had jumped to 51%. The individuals that owned shares in the subsidiaries were getting rich.

So in order for VinaCapital to remain aligned with the controlling shareholder, it took an equivalent stake in the subsidiary and tried to convince the sponsor to merge the subsidiary with the ListCo. But trying to restructure the business was difficult.

Since then, the ListCo has received a new controlling shareholder and VOF is working together with it to restructure the business. The overall business has been successful - it’s just that VinaCapital hasn’t been able to trust the management team to work in the best interests of minority shahorelders.

4. Never invest in a subsidiary

Subsidiaries are often established for the purpose of managing taxes or transferring profits to the parent. There will typically be related party transactions with the parent. And who knows whether those transactions will be done at arms-length prices.

Another problem with subsidiaries is the focus of the top management team. On what subsidiaries will the founder spend most of his time on?

An excellent example is Vietnam’s high-profile conglomerate Vingroup. It has interests in everything from residential property development to shopping malls, hotels, education and healthcare.

One of Vingroup’s newer subsidiaries is a car company called VinFast. The problem with this subsidiary is that the Chairman of Vingroup personally owns 41% of VinFast. While Vingroup itself has a decent reputation, it opens up questions about conflicts of interests down the road. VinFast is now transforming itself into an EV company and will most likely seek a US IPO at a high price. But by the sound of it, VOF will probably not be interested in VinFast or any other Vingroup subsidiary.

The numbers prove Andy’s point. If you had invested in the parent Vingroup in its IPO in 2007 until today, you would have enjoyed an annual return of 23%. But the success of Vingroup itself has not been replicated in any of Vingroup’s listed subsidiaries.

5. Never invest in a greenfield hotel

Vietnam’s tourism boom began in the early 2000s after the industry opened up. State-owned hotel operators sought to upgrade their properties, while international hotel companies like Sheraton wanted in.

In 2006, VinaCapital was asked to take over a project building a three-star hotel overlooking a beach in Nha Trang. The original budget for the project was US$34 million.

First, the project was upgraded from a 28-floor hotel to a five-star resort to be managed by an international hotel chain. International hotel companies have strict requirements for the hotels they manage, including the style of furnishing and the available amenities. Those upgrades weren’t cheap.

Second, inflation sky-rocketed in 2008 causing construction costs to rise 33% in a short period of time.

Third, the government complained about the hotel’s viewing tower being too high and causing an “encroachment of air space”. Causing the hotel to be forced to buy additional land-use rights in order to complete the construction.

By the time the hotel finally opened in 2010, the costs had ballooned to US$64 million. And with initial occupancy rates only reaching 22%, the project didn’t meet the stated ambitions. VinaCapital sold most of its stake in 2013 but continues to have a minority interest. The hotel has started to perform better more recently.

It’s better to invest in already-operating hotels with history and reputations. Another hotel investment VinaCapital was involved in, the Metropole Hotel in Hanoi, performed beautifully. It has a unique position as a colonial-style hotel in the heart of Hanoi’s old town. The scarcity of such hotels has made it into a trophy asset and enabled VinaCapital to earn a decent IRR on its investment.

6. Never build a hospital

In 2009, VinaCapital was approached by Dr Nguyen Huu Tung to fund the construction of a new hospital project in Ho Chi Minh City - the Hoan My Hospital Saigon.

At the time, only 5% of Vietnam’s hospitals and only 3% of beds were private. The private healthcare sector was booming, driven by a newly affluent population seeking better care.

The original budget for the 200-bed hospital was US$19 million with an estimated US$9 million for the building and US$6.5 million for the equipment.

But after construction had started, hospital equipment costs started to increase. Within just a year, the budget had swollen to US$40 million due to higher interest rates, high inflation and rising building and equipment costs. The project was starting to become a nightmare.

With rising costs, VinaCapital decided to invest in the parent, the hospital operator Hoan My Group, as well. And that proved to be a far superior decision. VinaCapital eventually sold its stake in Hoan My Group to India’s Fortis Healthcare and Richard Chandler Corporation at a profit less than two years later.

In greenfield construction, cost overruns are common, especially in healthcare where rising prices for equipment can cause budgets to exceed initial estimates in a short period of time.

7. Avoid export businesses and body shops

Andy doesn’t believe in “body shops” such as simple consumer electronics businesses or textile factories. Such operations tend to be a race to the bottom - the lowest cost operator will win, and there’s always a cheaper country to produce in. Such businesses typically operate at low margins. And they tend to be capital-intensive, providing a poor return on capital.

The capital intensive nature of the business has to do with working capital:

First, they need to pay for imported raw materials. It can take days or weeks before they arrive.

Then, the raw material will tie up capital as inventory.

The conversion to finished goods takes additional time.

Then the finished goods are shipped. It takes weeks to ship the product to the US and Europe.

And even then, the customer will typically only have to pay the manufacturer on 30-, 60- or even 90-day terms.

Throughout this process, the export business has to maintain working capital, financed through bank borrowings at rates of 6-10% per year. The export business almost becomes like a bank to their customer.

And while Vietnam’s labour costs are currently low, they are likely to rise over time. It also doesn’t have China’s scale in electronics manufacturing and Thailand’s scale in car manufacturing. It’s just a tough business to be in.

8. Never buy anything from another healthy fund or financial investor

If the seller is intelligent and the asset is supposed to be good, then why do they want to sell it? Why not just exit the investment via an IPO or a strategic sale?

There’s usually an information asymmetry between the seller and the buyer. The seller knows something that may or may not be discovered during the due diligence process. And that information asymmetry can be hard to deal with as an outsider.

It’s far better to buy an asset from a seller that is not healthy. For example, the seller might be closing down. An organisation might be restructured in a way that assets will need to be sold. Those are the situations when you as a buyer can get quality assets at bargain prices.

9. Never invest in a company belonging to your friend… or your enemy

If a friend is unsuccessful in obtaining a bank loan or an investment from a third party they may come to you for advice. And if you’re a kind person, you will naturally consider helping them.

In Vietnam, there will almost always be challenges along the way. Problems can usually be worked out, one way or another. But Andy found that if you’re dealing with a friend, the relationship will often be strained in the process. Either during the co-ownership of the company or when you try to exit from it.

So the rule then is never to invest in a company that belongs to your friend. If you have to, the best option will be a loan that’s clear on the interest, repayment date and the collateral.

10. No money out!

When making an investment, VOF wants the money invested to stay in the business - not be paid out to a shareholder or sponsor.

If the controlling shareholder uses cash received to start another business, he or she may lose focus on the original company.

In Andy’s experience, the most common uses for newfound wealth in Vietnam tends to be either of the following four categories:

Real estate

Gambling

Mistresses

Golf

All of these hobbies can lead to trouble in their own ways. For example, gambling is illegal in Vietnam and a conviction can lead to a prohibition to serve on company boards.

And mistresses can be expensive. Allegedly up to US$5,000/month for full board, clothes and car for the mistress, not even counting the marital strife and a loss of focus that can result from having mistresses.

For that reason and others, Andy thinks that female founders tend to be more focused on the business. They are less likely to gamble, they don’t play golf. And they tend to be more discreet.

11. Do not take promises at face value

Entrepreneurs will often make promises that everything is in order, that corporate governance systems are in place and that can deliver on their growth commitments.

In other words: “Trust, but verify”. There’s a good chance that not all of their promises will turn out to be true.

What’s especially common is that a company maintains two sets of books:

One set of tax books

One set of (secret) management books

While nobody likes to pay taxes, companies that haven’t paid their taxes will eventually need to admit the problem. Overhanging tax liabilities can be solved, of course, but they need to be brought to light.

12. Get official documents for all transactions

Vietnam’s bureaucracy is notorious for its complexity. Documents will require official red stamps. Then there’s the “red invoice” - official receipts for products and services that prove that a company has paid VAT.

Just like in China, each Vietnamese business has a “company chop”. It’s one of the most important assets for any business. With the company chop, you can authorise payment or publish official notices. Every signature will need to have a stamp from the company chop.

The key is this: the person who has the chop has effective power over the organisation. And that is not an exaggeration.

Andy tells the story of a husband-and-wife team running a company in Vietnam. The marriage fell apart and the wife ran off to Australia, company chop in her hand. And once she left, her ex-husband back in Vietnam was unable to transact company business. The organisation ended up paralysed.

So before VinaCapital or VOF invest in any company, they’ll want official documentation with the requisite red stamps. If the company cannot produce them, they’ll just walk away.

13. Perform health and background checks on key executives

In smaller companies, the fortunes of the business are often tied to the original founder. If he or she is falling sick, then the value of the business could be impaired.

Many years ago, VinaCapital was presented with an opportunity to invest in a wire company in Ngo Han.

Just before the final investment was to take place, the CEO died from cancer and there was no successor. He had kept his illness a secret.

From then on, Andy and his team learned to conduct thorough background and health checks on all businesses they invest in. That also includes investigating the founder’s personal spending, past civil disputes and other family connections within the company.

14. Consider the risk of marriages falling apart

Then there’s a risk that marriages break apart. That could spell trouble if the business is run by a husband-wife team, and they suddenly start fighting against each other.

Consider the case of Trang Nguyen Corporation, the most successful coffee company in Vietnam. It was run by a husband-wife team of Dang Le Nguyen Vu and Le Hoang Diep Thao, known in the press as the “Coffee King” and the “Coffee Queen” of Vietnam.

When the company was founded, the “King” served as Chairman and CEO and the “Queen” as deputy general director. But in actuality, she was the person running the business. But in 2013, the King retreated to the mountains of Vietnam to meditate. While he was meditating, the Queen ran the company and the business became an incredible success story.

But in 2015, she filed for divorce. The King came back and as revenge, the King ousted her from the company. After years of legal drama, the court ruled that the King would receive 60% of shared assets and control of the group.

Meanwhile, the company suffered. In 2018, profits fell 50%. The Queen went on to start her own coffee brand “King Coffee” - perhaps a thinly veiled attempt to get back at him. And now they continue to fight, each with their own competing brands.

15. When in doubt, put it in the assumptions section of the letter of intent

One way of dealing with the information asymmetry in a new investment is to provide the seller with a letter of intent. The statement section will include assumptions about the family, the CEO’s health, that none of the management team has criminal records, that there have been no discussions of divorce, use of funding, etc.

The sponsor will usually correct any mistaken assumptions. And if he or she is not forthright, then that calls into question the sponsor’s trustworthiness.

16. Any promise can be broken if it’s not written down in a signed document.

Since disputes often end up in arbitration courts in Singapore or Hong Kong, it’s often best to have all important documents in two languages - both Vietnamese and English. That way you can avoid mistranslations and misunderstandings.

17. Always have an exit clause, even if you have to pay a penalty

Exits can usually happen through either a trade sale or an IPO. Consumer-facing businesses are usually easy to IPO because the products will be familiar to retail investors.

But industrial companies and other B2B businesses may have difficulties going public. In preparing for a sale, VinaCapital typically helps companies strengthen their brand names, their distribution channels or their manufacturing capabilities.

Andy talks about VOF’s investment in vodka company Halico. Its Hanoi Vodka brand was well known and seen as a strategic asset for international buyers. In preparing for the exit, VinaCapital helped them develop all these three areas, which helped drive sales, especially through improved distribution and marketing.

In 2011, VOF sold the company to Diageo, which saw Halico as a way to gain access to the company's distribution network throughout Vietnam.

18. Put money in escrow with third-party banks

After the negotiations of investment have been finalised, money will typically be put in an escrow account.

Andy mentions the case of a co-investment with a Japanese company. After the money had been placed in the escrow account, VOF wanted to renegotiate the terms. But the bank simply ignored them.

The problem was that the escrow account was with a related party bank. And as they held on to the capital sitting in escrow, they earned interest on it.

The lesson was that escrow accounts should always be at one of the large state-owned commercial banks. Or failing that, one of the international bank branches, such as Standard Chartered or Citibank.

19. Think three times when exercising a convertible loan

Convertibility features typically allow the owner to convert their loan to equity within a 2-3 year time.

While it can be tempting to convert to an equity holder, your downside protection is far less than as a debt holder. Convertibility features offer optionality, and optionality is valuable. And since you’ll be converted to a minority shareholder, you might end up in a vulnerable situation of being a minority investor in a company that’s not run for your benefit.

So think twice before converting.

20. Don’t take control - use drag-along rights

Taking control of a business can be messy. You’ll have to find a new CEO to run the business. You’d be responsible for the company’s representations, warrants and contingent liabilities.

A solution is so-called “drag-along rights”. Such rights enable you to gain a controlling 51% share in the business with the option to sell that stake to a third-party buyer. And while the original sponsor may “lose their baby” so to speak, it will be a less messy divorce than trying to effect change as a minority shareholder.

Conclusion

Today, the Vietnamese stock market index trades at just 13.7x P/E - a low multiple compared to other global stock markets.

The Vietnamese growth story is compelling. Economic growth in emerging markets is typically driven by light manufacturing exports, and Vietnam excels in that area. Vietnam will be a much richer country 5-10 years from today.

There are some signs of froth in the stock market. Trading volumes have been elevated during the pandemic, suggesting high retail participation - and perhaps even speculative activity. I would imagine that the Vietnamese economy will experience boom-bust cycles just like any other developing country, and that’s okay.

One question mark is Vietnam’s capital controls. It’s challenging to transfer capital out of the country.

So what can a newly affluent Vietnamese do with his or her money? They can invest in property domestically or in the stock market. That could be a reason why we’re now observing cap rates as low as 2-3% in central parts of Ho Chi Minh City, despite high mortgage rates of 7-8%.

The question is what would happen to the exchange rate and asset prices if the capital account was liberalised. At what prices would markets clear?

Then there’s a broader question about politics. Vietnam is still a communist country, at least in name.

Will private property rights be respected by future Communist Party leaders? Recently, there have been echoes of Xi Jinping in the Communist Party of Vietnam’s new anti-corruption campaign. As with China, you can never be sure whether the campaign is simply an effort to deal with corruption or to neutralise businessmen who aren’t loyal to the communist party elite.

But so far, Vietnam is developing faster than almost any other country on earth. It’s an exciting story. Andy Ho’s book is a fun read for those who want an insider’s account of what it’s like investing in a frontier market such as Vietnam. The stories he tells - and the honesty with which he tells them - can’t be found anywhere else.

Thank you for reading!

Sign up for over 20 deep-dive reports on Asian stocks per year and full disclosure of my personal portfolio. I will be happy to see you join!