Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.

Summary

- After Ben Keswick took over Jardine Matheson, the company has slowly transitioned away from being an owner-operator to more of a portfolio manager.

- The privatization of Jardine Strategic was under-priced, but it also simplified the corporate structure. That should be positive for minorities in the long term.

- Jardine Matheson’s own board has now been stacked with private equity professionals. And new CEO Lincoln Pan comes from private equity firm PAG, where he built up its non-China business.

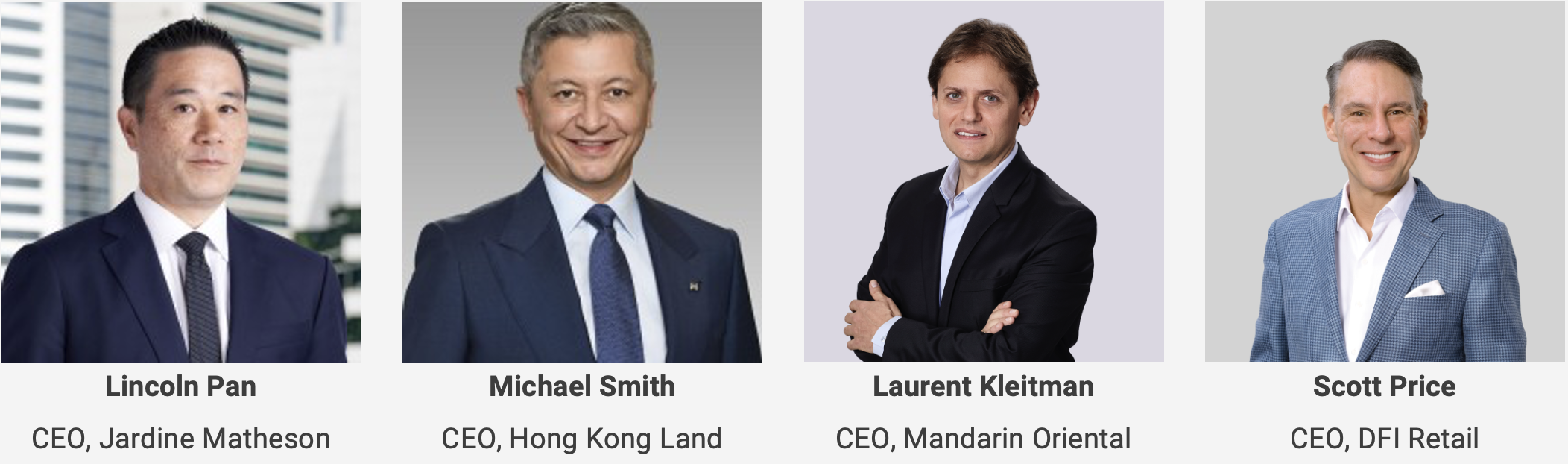

- The CEOs of several of Jardine Matheson’s listed subsidiaries have also been replaced, including at Hong Kong Land, DFI Retail and Mandarin Oriental.

- In this post, I discuss the reforms that have taken place within the group and the implications for each of the portfolio companies.

Jardine Matheson is one of the original Hong Kong trading houses that has survived to the present day - a sprawling network of companies serving consumers in Asia.

The performance of Jardine’s companies has been weak in the past few years. But after Ben Keswick took over in 2019, significant changes have taken place. Most importantly, Jardine Matheson is moving towards a decentralized structure where it’s becoming more of an investor than an owner-operator.

In this post, I’ll explain exactly what those changes are. And the implications for each of the portfolio companies.

Table of contents:

1. Introduction to Jardines Matheson

2. An overview of the group today

3. The 2025 reform agenda

4. The investable universe of stocks

5. Conclusion1. Introduction to Jardine Matheson

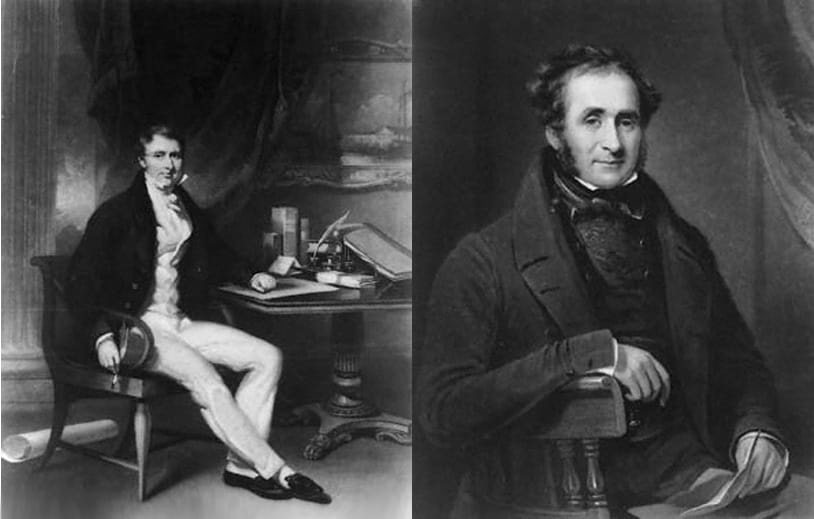

Jardines was one of Hong Kong’s original trading houses, also known as “hongs”. It was set up as a partnership between William Jardine and James Matheson — two Scottish businessmen — to serve as a trading operation between different parts of the British Empire.

They had met in British-controlled Bombay in 1820, then moved to Canton, where they took over a previous partnership into their own hands. Once Hong Kong became British in 1841, they shifted their operations there and bought the first piece of land ever sold in Hong Kong, close to what is today considered to be Causeway Bay.

Initially, the Jardine Matheson partnership was active in the trading of opium, tea and cotton, primarily from India to the rest of Asia. It owned a network of steamships that transported products along the Chinese coast and into Japan.

In the 1850s, a Scotsman named William Keswick came to Hong Kong and married the niece of William Jardine. He established the Japanese office of Jardine Matheson in the trading hub of Yokohama. And eventually he became managing partner — the so-called “tai-pan” — of the entire business in the late 1880s. And that’s how the Keswick family ended up in control of the whole group.

After William Keswick stepped down in 1889, Jardine Matheson started to diversify into other industries. For example, it set up Hong Kong Land to build offices in Hong Kong’s central business district. It set up mills and cotton spinning companies in Shanghai in 1895. It set up a construction company in 1923 to build properties and infrastructure assets. And it launched an EWO-branded brewery in Shanghai in 1935.

After the communists took over the Chinese Mainland in 1949, Jardine lost all of its Shanghai assets. But it retained its Hong Kong operations and instead expanded the business to other parts of Asia.

A pivotal point in the development of the group was the involvement of Henry Keswick, the great-grandson of William Keswick. He was born in Shanghai in 1938, studied at Eton and Trinity College before moving back to Asia in the 1950s. After Jardine Matheson became a public company in 1961, Henry became the most powerful individual within the business. Much thanks to his deal-making, its total assets grew from US$70 million in the early 1970s to US$27 billion by 2018.

Some of Henry’s biggest deals included buying Reunion Properties in 1973, doubling the group’s assets in one go. The Hong Kong stock market was on a tear at the time, and Jardine Matheson only had to issue 7% more shares to finance the acquisition. Henry also acquired the Theo H. Davies sugar trading operation in 1973, just before a multi-year bull market in sugar.

He built the Mandarin Hotel in Hong Kong and eventually merged it with The Oriental Hotel in Bangkok, forming the base of the Mandarin Oriental hospitality group. He built a Hong Kong-based property business called Gammon Construction as well as a Mercedes dealership called Zung Fu. He turned Dairy Farm into a pan-Asian retailer running supermarkets, 7-Eleven stores, pharmacies, IKEA stores and bakeries. And he also built up brokerage firm Jardine Fleming before selling it to JPMorgan Chase.

But his biggest home run might have been the acquisition of Indonesian auto distributor Astra International after the Asian Financial Crisis in 2001. In the following 25 years, the share price has gone up by a factor of 36x, and the stock still trades at no more than 7x P/E.

That said, Henry Keswick was no friend of minority shareholders. Under his supervision, Jardine Matheson built up a complex corporate structure designed to entrench Keswick family control. To that end, he set up Jardine Strategic in 1986, with reciprocal share ownership that amplified the family’s voting power.

The corporate structure has improved a bit in recent years, but many question why this complex corporate structure is necessary, whether this pyramid of listed companies is simply designed to keep the family in control, potentially at the expense of us minorities.

2. An overview of the group today

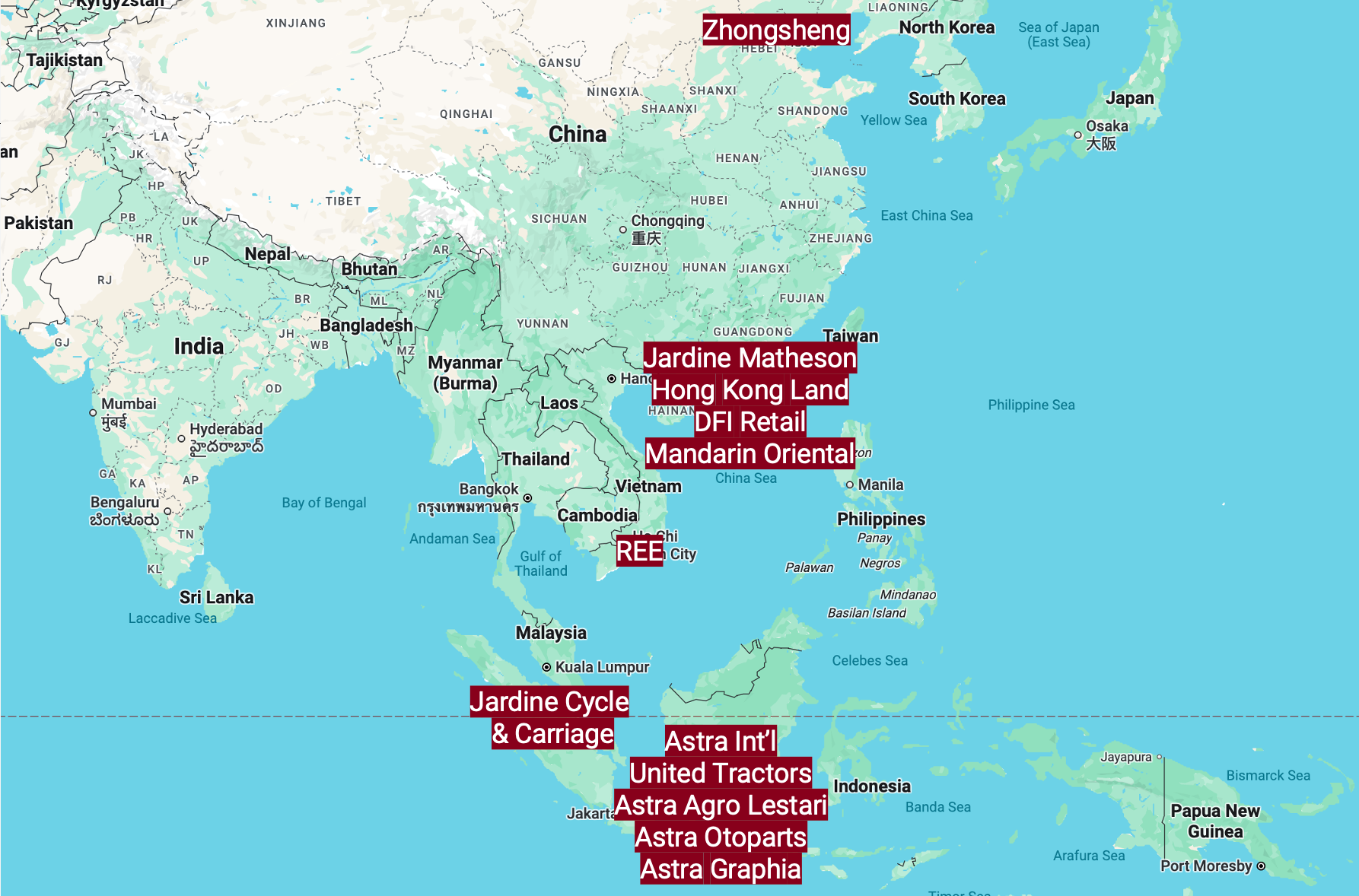

The Jardine Matheson is today a massive empire of companies operating across the Asia-Pacific, employing a total of 450,000 staff. They operate in two primary regions: China and Southeast Asia.

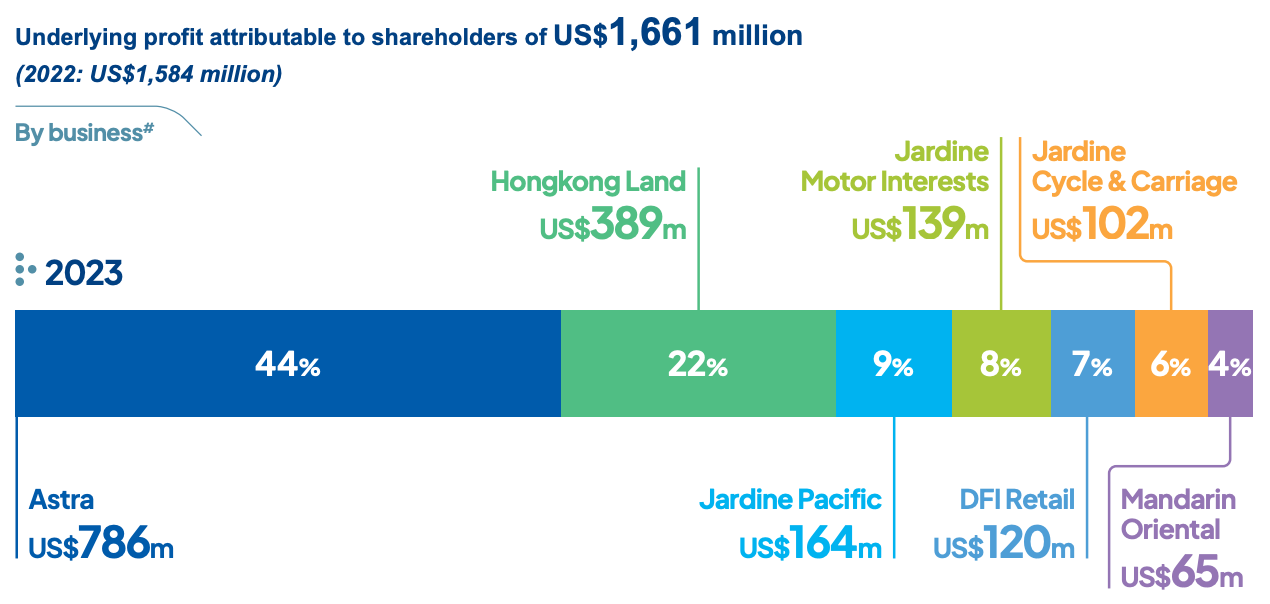

In 2024, roughly 70% of underlying net profit came from Southeast Asia, and much of that from Indonesian auto distributor Astra International.

After the sale of supermarket chain Yonghui Superstores, the only Mainland Chinese company in the portfolio is auto distributor Zhongsheng. In Hong Kong, you’ll find a big part of the Jardine Matheson bureaucracy. Jardine Matheson is based in Hong Kong, as is commercial property owner Hong Kong Land, hotel developer Mandarin Oriental and retail operator DFI Retail.

The Southeast Asian business is mostly controlled through a separately listed subsidiary, Jardine Cycle & Carriage. Through this entity, Jardines controls a majority stake in Astra International, which in turn owns a number of major Indonesian businesses:

- United Tractors sells heavy machinery from Komatsu and operates coal mining businesses

- Astra Agro Lestari owns oil palm plantations

- Astra Otoparts sells automotive components to its parent company

- And finally, Astra Graphia is an IT consulting and printing services business

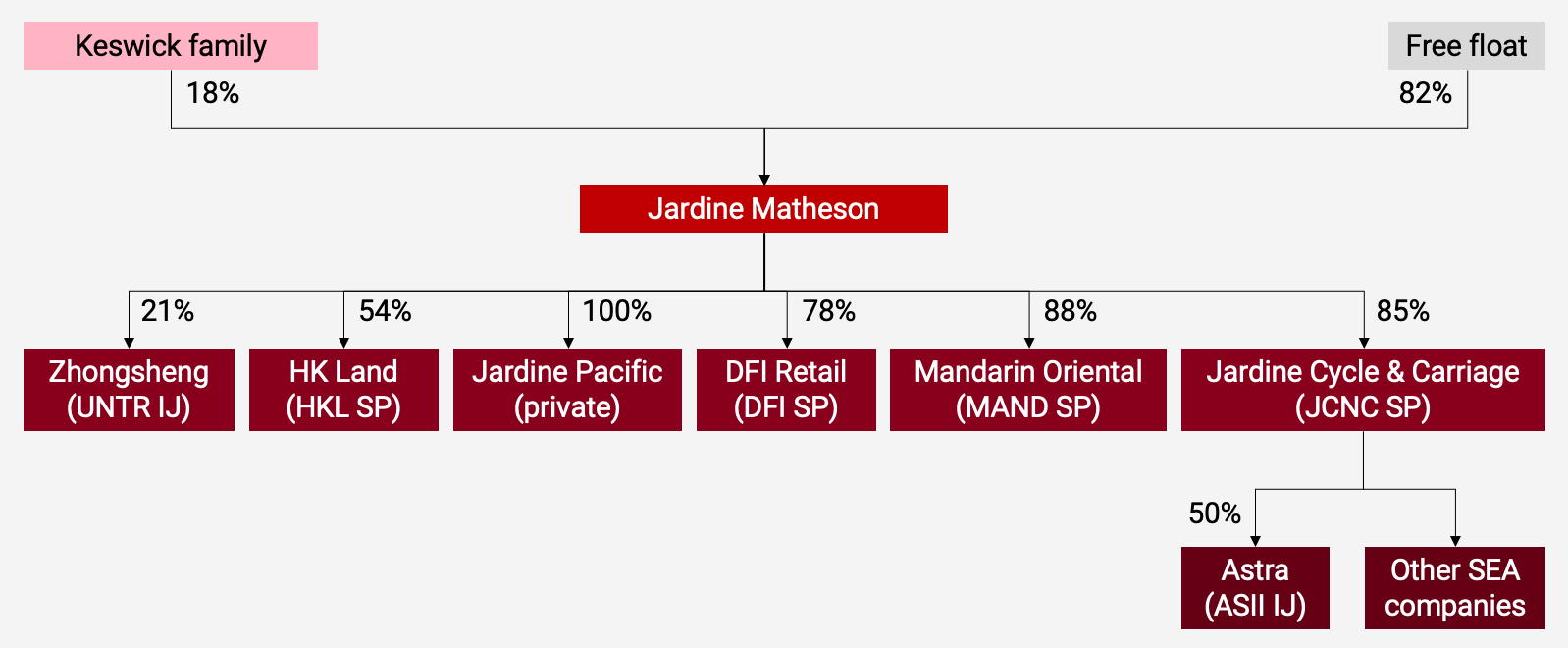

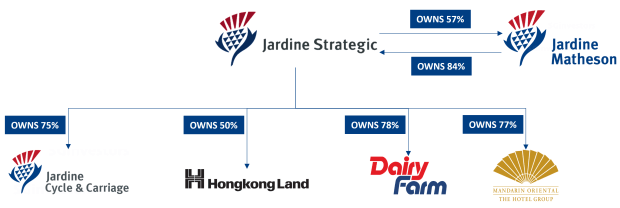

Here is Jardine Matheson’s corporate structure as it looks today:

The Keswick family controls only 18% of Jardine Matheson and only 18% of the votes, so it’s not entirely in control anymore. The employee stock option plan represents another 13%, and then you have value funds such as First Eagle and Orbis participating with smaller stakes.

Note, however, that most of the subsidiaries are >50% owned by Jardine Matheson, so they are fully in control of them, putting their minorities at risk. That’s something that Jardine Strategic shareholders got to experience first-hand.

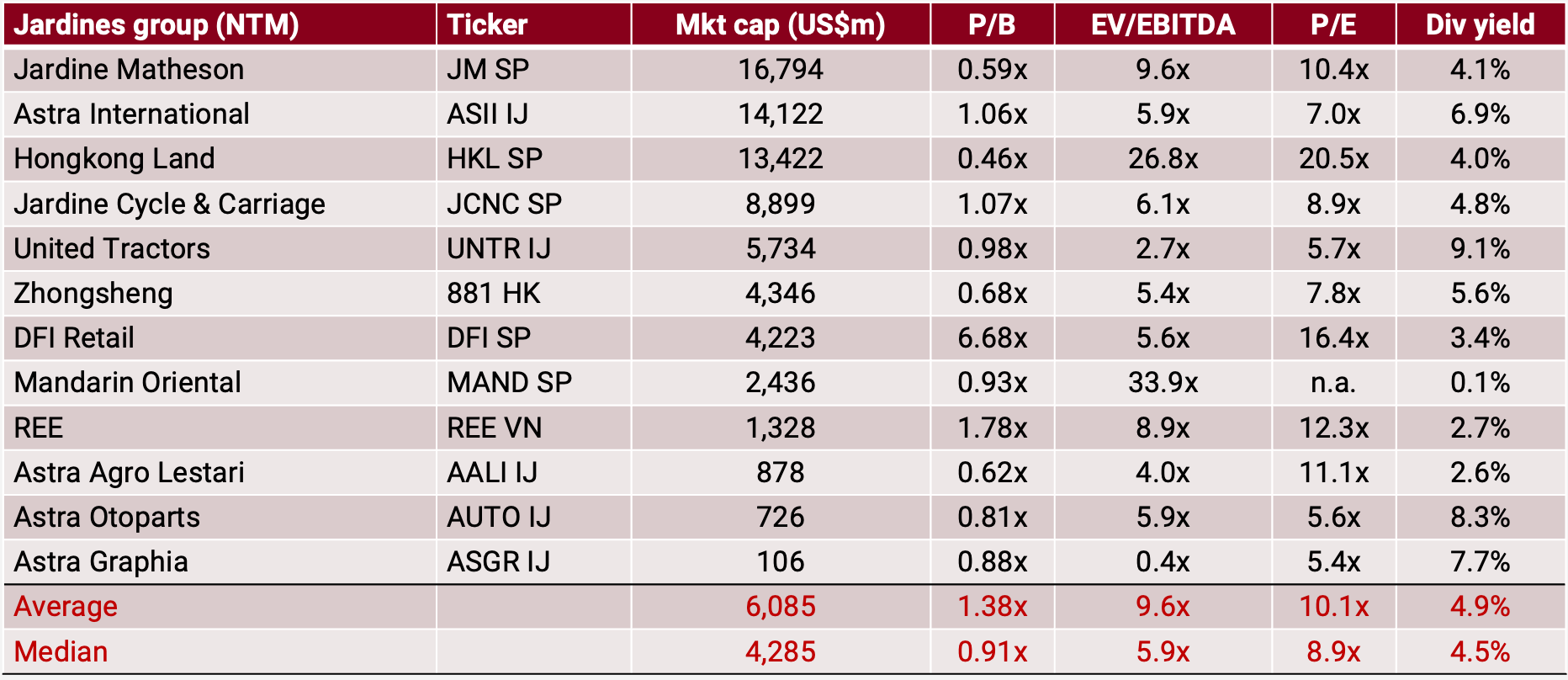

Neither of the stocks looks particularly expensive, with the average Jardine company trading at no more than 10x P/E. There are good reasons for that, with some investors thinking that the group is perhaps behind its time. But perhaps the current reform agenda can eventually put the group on the right track.

3. The 2025 reform agenda

After Henry Keswick stepped down as Chairman in 2018, his nephew Ben Keswick took over the group.

And finally, we’re starting to see changes taking place.

The most significant shift was the 2021 privatization of Jardine Strategic. Jardine Matheson used to own 84% of Jardine Strategic, and Jardine Strategic, in turn, owned 57% of Jardine Matheson in a cross-holding structure. In the privatization, Jardine Matheson put in a US$5.5 billion bid for the remaining 15% it didn’t already own and cancelled its stake in Jardine Matheson.

Shareholders revolted because the US$33/share offer represented a 43% discount to Jardine Strategic’s net asset value/share of US$58. But since Jardine Matheson controlled more than 75% of the required votes, the deal went through, and Jardine Strategic minorities just had to suck it up.

On the positive side, Jardine Matheson’s corporate structure is now simpler with less room for minority abuse, at least in the top part of the structure.

But there’s a broader change taking place within the group. Ben Keswick has committed to a transition for Jardine Matheson from an owner-operator to a portfolio manager. In his own words:

“We have been on an ongoing transition away from our historical owner-operator model, towards becoming an engaged investor with a sharpened focus on generating superior, long-term returns for shareholders”

The board has become much leaner than before: now just nine directors vs 14 previously. What’s particularly bullish is that a number of private equity executives have joined the board. For example, Carlyle’s Janine Feng joined the board in May 2023, economist Keyu Jin joined in January 2024, KKR’s Ming Lu joined in February 2025, and investment banker Tim Wise joined in May 2025. This shift towards finance professionals on the board probably signals that Jardine is taking the “portfolio approach” to management seriously.

And we’re also seeing progress within the top executive ranks. Former private equity executive Lincoln Pan has now taken over as CEO. He has a great reputation and was almost solely responsible for building up private equity group PAG’s non-China business. He has a JD from Harvard Law School and a background as a McKinsey consultant.

There’s also been a number of new hires in Jardine’s portfolio companies:

- August 2023: DFI Retail’s new CEO, Scott Price, is an American who was previously in senior positions at Coca-Cola Japan, DHL Express Japan and Walmart Asia. He has degrees from the University of North Carolina and the University of Virginia. He’s known to be a turnaround expert and has taken several steps to streamline the portfolio.

- September 2023: Mandarin Oriental’s new CEO, Laurent Kleitman, came from Christian Dior, where he headed up the perfume division. Before that, he was president of the consumer beauty division of Coty. He also spent 25 years at Unilever. Since he took over, he has been focused on building the Mandarin Oriental brand, which I think is exactly what is needed here, rather than property development.

- April 2024: Hong Kong Land’s new CEO, Michael Smith, comes from real estate manager Mapletree, where he was a regional CEO for Europe and the US. Prior to that, he spent 11 years at Goldman Sachs and 10 years at UBS, both in investment banking. He’s originally from Australia with a degree from the University of South Australia. Since taking over, he has been pushing to exit China and reinvest capital into higher-return vehicles.

The talent of these CEOs will matter more and more as Jardine is moving towards a decentralized structure. The portfolio company CEOs will focus on the operational side of things, while Lincoln Pan oversees overall capital allocation within the group — a bit like at Berkshire Hathaway.

One practical aspect of this decentralization is that Jardine has now scrapped its graduate trainee program. Instead of rotating between Jardine portfolio companies, talent is now encouraged to focus their careers on each of the single entities, serving them, not the parent. I think that’s a great development.

Executive remuneration within Jardine Matheson is apparently based on four key priorities: evolving the portfolio, enhancing entrepreneurialism, driving innovation and operational excellence and embedding sustainability. I’m finding these targets very fuzzy and wonder if they’ll help Lincoln Pan drive returns appropriately.

On the website, however, Jardine Matheson does state four financial objectives that are much more concrete in their nature: 1) high-quality long-term growth of earnings and cash flows 2) investment ROICs higher than WACC 3) NAV per share growth and 4) progressive dividends. Poor acquisitions will penalize executives on ROIC, so hopefully these guidelines will prevent what Peter Lynch used to call “diworsification”.

Within the portfolio companies, executive remuneration now seems more straightforward than it used to be. For example,

- At Hong Kong Land, the share-based portion is now measured on total shareholder return vs the cost of equity and vs peers over a 3-5 year time frame.

- At DFI Retail, pay is now based on both total shareholder return and the return on capital.

- At Mandarin Oriental, bonuses are based more on qualitative factors such as brand perception.

So, overall, remuneration policies have improved, though how much differs from subsidiary to subsidiary.

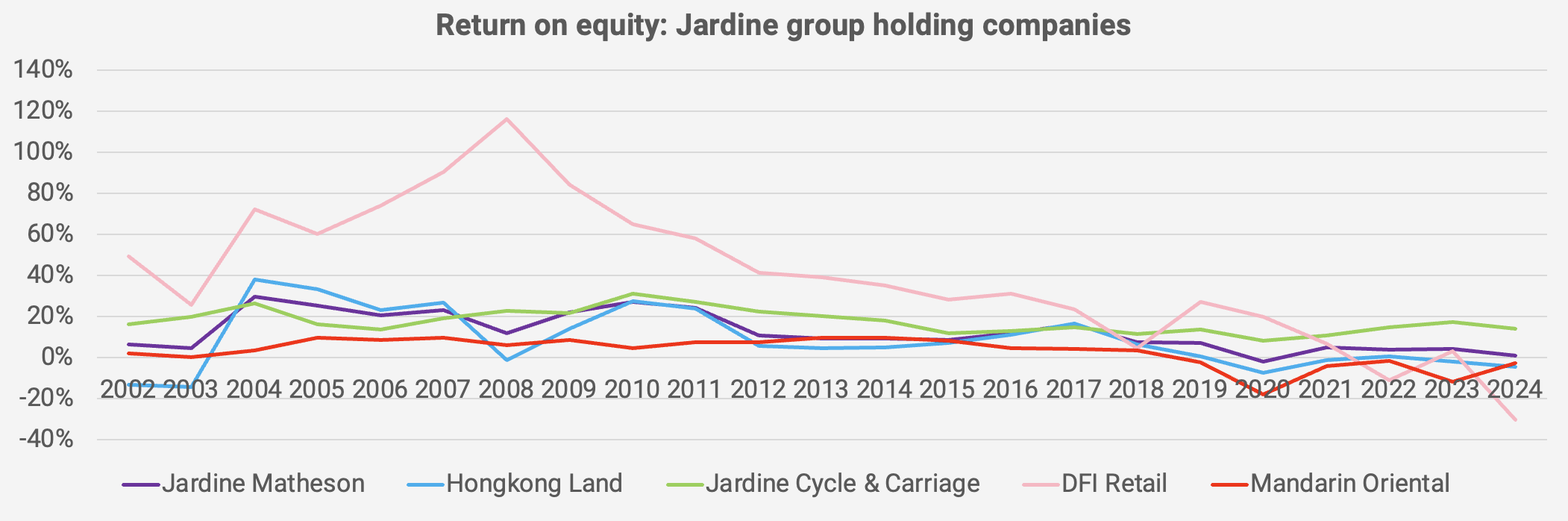

With all these changes taking place, has Jardine Matheson’s capital allocation improved? That remains to be seen. There has been no obvious improvement to the return on equity of Jardine’s main holding companies:

Though some of the group’s recent M&A deals have indeed been encouraging:

- In April 2024, Mandarin Oriental sold its Paris hotel property for US$227 million, as well as the associated retail space for US$160 million. It retains the management contract for the Paris hotel, so this transaction seems to be aimed at moving towards a more asset-light model. I love to see it.

- In September 2024, DFI Retail sold its 21% stake in Yonghui Superstores at a big loss. It was unprofitable at the time, and Scott pointed to DFI Retail’s new strategy of divesting unprofitable companies. DFI Retail also divested its 22% stake in Robinson Retail in the Philippines and Cold Storage & Giant supermarkets in Singapore. The proceeds from these divestments will be used to pay down debt and then reinvest in pharmacies and 7-Eleven stores. And he even paid out a US$600 million special dividend, directly benefitting DFI Retail’s minority shareholders.

- In April 2025, Hong Kong Land sold a number of One Exchange Square floors to Hong Kong Exchange and Clearing for HK$6.3 billion. This included 147,000 square feet of floor space from floors 42 to 50, where HKEX already occupies office space. The rental yield was a relatively low 2.9% — in fact, lower than Hong Kong’s 10-year government bond yield. So I think the transaction made perfect sense from the point of view of Hong Kong Land. The proceeds will be used for debt reduction and share repurchases, as management believes the stock continues to be undervalued.

- In early 2024, Jardine Cycle & Carriage sold barely profitable Siam City Cement for US$99 million and reinvested the capital in fast-growing Vietnamese mini-conglomerate REE.

So overall, I think these moves are a step in the right direction. I’m particularly positive about Michael Smith at Hong Kong Land, as he seems to have the right mindset when it comes to capital allocation.

4. The investable universe of stocks

4.1. Jardine Matheson (JM SP)