Table of Contents

Disclaimer: Asian Century Stocks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to discuss your investment options with your financial advisers and to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs. From time to time, I may have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website. Note that this is a disclosure and not a recommendation to buy or sell.

Summary

- The Japanese Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) industry has dozens of companies listed, and many of them are growing rapidly with decent unit economics.

- This post is an “initiation of coverage” of the industry, discussing the SaaS business model, how to think about the sector, industry trends and the investable universe of stocks.

- Ideally, a SaaS company should have a best-in-class product, a large total addressable market, high switching costs, high sales productivity and a low valuation multiple.

- Some of the key trends in the industry include a catch-up of the still-low penetration rate of SaaS products, a continuous shift from on-premise to cloud, a government digital transformation push, outsourcing of software development, and disruption from generative AI tools.

- The investable universe of stocks spans horizontal ERP providers such as OBIC, accounting software providers such as freee, vertical SaaS companies such as Temairazu and collaboration software developer Cybozu. I go through each of them in depth.

In 2011, Marc Andreessen said that software is eating the world. However, Japan didn’t get the memo. A conservative, hardware-centric culture continues to permeate the Japanese IT industry.

However, a few dozen listed software developers are pushing the country into the new era of software-first products. I’m speaking of Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) companies that charge for their software using subscription models.

While I’m generally skeptical about software companies, I think the SaaS model is attractive. Subscription revenues are recurring, stable, and predictable. Online mass distribution leads to high margins at the horizon. The total addressable market is often large, providing a whitespace for growth.

I’ve spent the last week trying to understand the sector. Many others have written thoughtful commentary on SaaS companies, including Made in Japan, Japan Business Insights, Nippon Nuggets and Find the Moat.

This post can be seen as an “initiation of coverage.” Given the plethora of opportunities in Japan’s SaaS industry, I plan to write about it for years to come.

Table of contents

1. Software-as-a-Service: the basics

1.1. The SaaS business model

1.2. Acquiring new customers

1.3. Retaining customers

1.4. Monetizing customers

2. Stock picking among SaaS names

2.1. Best-in-class product

2.2. Large total addressable market

2.3. High switching costs

2.4. High sales productivity

2.5. Low valuation multiples

3. Trends in Japan’s SaaS industry

3.1. Rising SaaS penetration

3.2. A shift from on-premise to SaaS

3.3. The government’s digitalization push

3.4. The rise of Vertical SaaS

3.5. Outsourcing to Vietnam and elsewhere

3.6. Disruption from generative AI tools

4. The investable universe of stocks

4.1. Horizontal ERP

4.2. Vertical ERP

4.3. Collaboration software

4.4. Data services tools

5. Conclusion1. Software-as-a-Service: the basics

1.1. The SaaS business model

Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) is not an industry per se - it’s more of a delivery mechanism for software.

In the past, software was sold through one-off licenses that made up the majority of the cost. The software was installed on customers’ computers. Over time, they would pay maintenance fees to receive continuous support until the software became outdated.

Internet connectivity changed this entire model. By storing data online (“on the cloud”) rather than on-premise, it could suddenly be accessed from anywhere. Customers now pay monthly or yearly for access to the software. And any updates are made seamlessly without any disruption to customer workflows.

The benefits of the SaaS model are multifold:

- There’s no need to send out individuals to install the software on-premise

- It reduces the up-front costs for the customer

- Small companies can scale up their expenses slowly, in line with revenues

- Clients can then access the software from any device, e.g. with a web browser

- The cost of SaaS products also tends to be low in absolute terms, given the low marginal cost of production

- And finally, the software is updated continuously without any disruptions

So, how about vendors - will they benefit, too? In theory, the transition should be helpful - if they gain enough scale to pay for initial development costs. Many SaaS companies earn gross margins of close to 80-90%. Even if a SaaS company isn’t profitable today, it might become profitable at scale.

On the other hand, competition is greater online. And the switching costs of moving from one service to another are much lower than if the software has been custom-made and installed by say a system integrator on client computers.

Then there’s the cost of finding customers. Sales and marketing costs frequently make up 75% - if not more - of total expenses. So, the yearly or monthly subscription fees must compensate for the often significant costs of acquiring each customer.

You could also argue that SaaS companies are also in the hands of cloud service providers such as Amazon Web Services and Microsoft Azure. SaaS developers need to pay these providers for storage, computation, and other services. AWS even has a marketplace with many competitors directly with SaaS companies themselves.

So, I don’t think it’s as easy as saying that SaaS is necessarily superior. But if developers can get their business models right, develop unique software that becomes deeply embedded in client workflows, and charge an amount that justifies customer acquisition cost, then they can indeed become future cash flow machines.

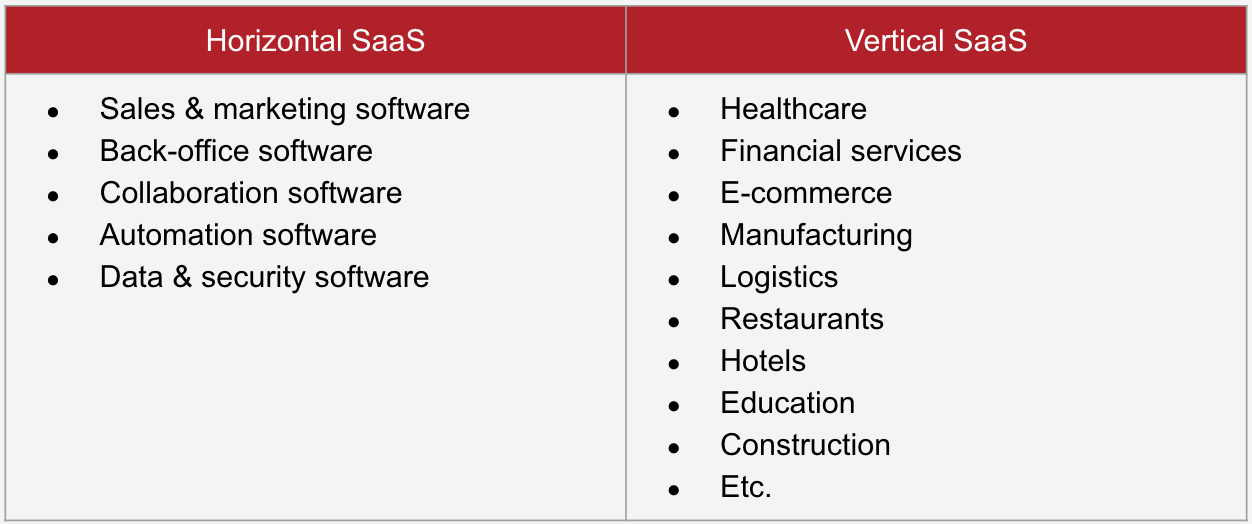

We can broadly divide the industry into two categories:

- Horizontal SaaS: Software designed to cater to a broad audience

- Vertical SaaS: Software purpose-built for a particular industry

Among these two, vertical SaaS solutions seem to be taking market share. Examples include data management software for hospitals or inventory management software for logistics companies.

So, how do you find success in the industry? Logically, success must come from three separate factors: acquiring new customers, retaining customers and then monetizing those same customers. Each deserves a discussion of its own.

1.2. Acquiring new customers

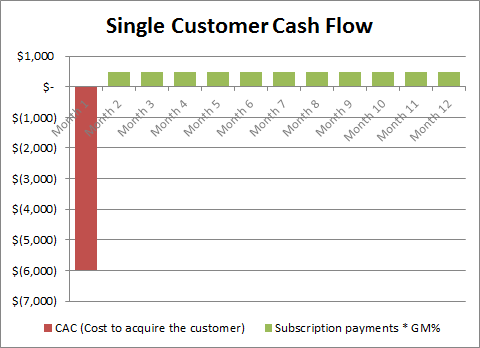

The SaaS business model is unique because customer acquisition costs are taken upfront, while subscription revenues occur in subsequent periods. That means that SaaS company cash flows tend to be negative initially and then positive later. In other words, SaaS companies need investments to get them off the ground.

On the other hand, if customers pay yearly rather than monthly, the company will get an entire year’s worth of revenues on day 1. That cash flow should help pay for some of those initial investments.

Finding a new subscriber is known as customer acquisition cost (CAC). A SaaS company’s sales and marketing costs are a proxy for the CAC. To calculate it, take the total sales and marketing expenses and divide them by the number of new customers.

Since acquiring customers is costly, faster growth leads to weaker cash flows in the short term. The new customer will bring in a great deal of revenue over his total lifetime, but initially, the company will see a squeeze on profitability and cash flow. In the words of Ron Gill at Netsuite:

“If plans go well, you may decide it is time to hit the accelerator (increasing spending on lead generation, hiring additional sales reps, adding data center capacity, etc.) in order to pick-up the pace of customer acquisition. The thing that surprises many investors and boards of directors about the SaaS model is that, even with perfect execution, an acceleration of growth will often be accompanied by a squeeze on profitability and cash flow.”

So, don’t fear initial losses in the early stages of a SaaS company’s growth journey. These could be due to a mismatch in the timing of costs, with development costs, sales, and marketing expensed immediately and revenues recognized over time.

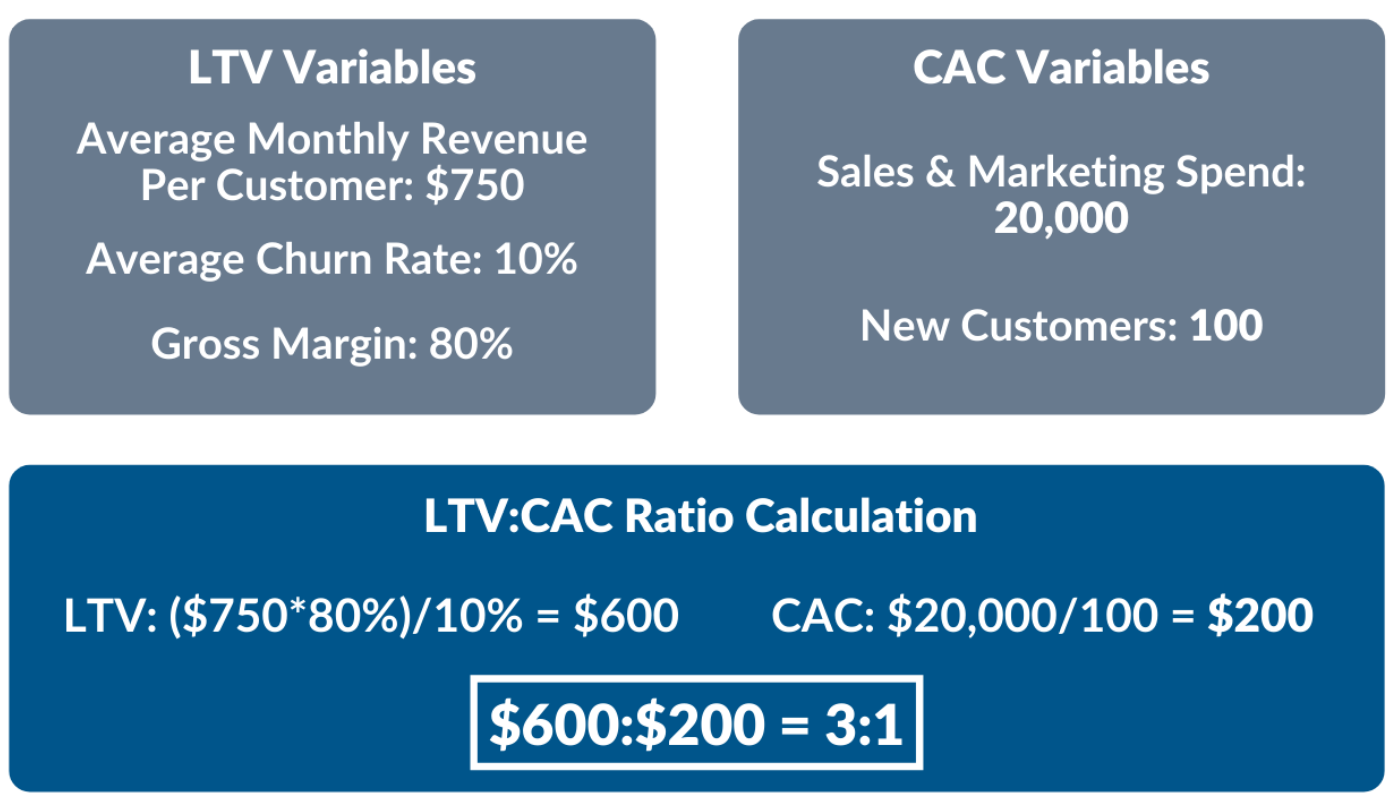

To understand whether spending money on growth makes sense, you’ll need to weigh the cost of acquiring a customer (customer acquisition cost) with the lifetime revenues that the customer brings in, also known as customer lifetime value (“LTV”). Part of the calculation is the churn rate - how many stop paying within the first year.

- Customer acquisition cost (CAC) = sales & marketing expense / new customers

- Lifetime value (LTV) = Average revenue per user (ARPU) * gross margin / churn rate

If the LTV/CAC ratio is above 3x, ramping up spending on acquiring the customer usually makes sense. The LTV/CAC ratio will typically depend on your go-to-market strategy and will not be static.

For example, for Asian Century Stocks, the average lifetime value of a subscriber is about US$500. CAC therefore shouldn’t be higher than US$167. If my sales & marketing expenses are LinkedIn ads, and 1% of clicks lead to a paying customer, then I know that each ad shouldn’t cost more than $1.7 per click. For reference, a LinkedIn ad costs about US$5 per click, so this go-to-market strategy wouldn’t make sense given these numbers.

Another way to evaluate the cost of acquiring new customers is to look at the number of months it takes to recover the cost. You should get back your money within 12 months, and ideally, as fast as 5-7 months.

If the company can grow consistently by purchasing ads or through an in-house sales organization, you’ll want to ramp up that spending and enjoy that flywheel. You’ll end up with a growth machine - at least for now.

The key factor driving a high LTV/CAC ratio is customer love for the product. The software needs to offer something special and perhaps be deeply embedded in the customer’s organization. Such a value proposition ultimately leads to a low churn rate and high customer lifetime value.

To acquire new customers, SaaS companies employ different go-to-market strategies. They might spend money on ads, as mentioned above. They might spend money increasing their reach on social media or search engines. They might pay system integrators or resellers to distribute the product. Or they might employ sales staff, who engage in cold outreach to get new leads.

SaaS companies should consider all of these options and evaluate each lead source's return on investment, using LTV/CAC as a yardstick.

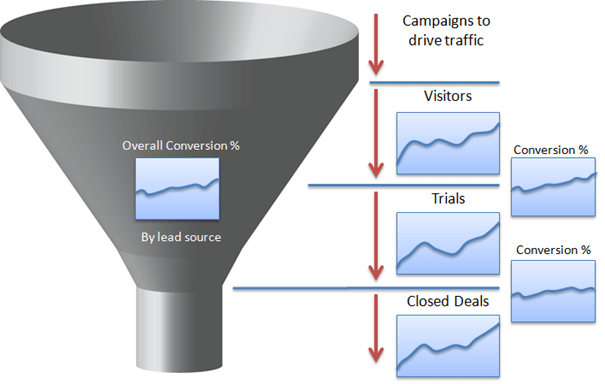

Conversion of new leads into paying customers can be pictured as a funnel that gets smaller based on some conversion rate. Many companies offer free versions of their software (the “freemium model”) and then up-sell value-added services for those who become paying subscribers.

Early on in the development of SaaS product, the company should be focused on securing new leads, offering free trials and converting them into paid customers. But over time, the company will want to switch its focus to retaining old customers and improve the customer lifetime value that way.

1.3. Retaining customers

The most important number that SaaS investors focus on is Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR). It refers to the normalized yearly revenues the company expects from its existing customers. If a company gets paid monthly, it’s known as the Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR).

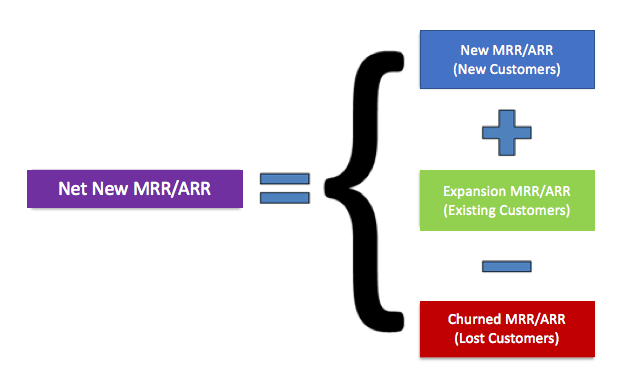

To grow annual recurring revenues, a company needs to either find new customers (“new ARR”), sell more to existing customers (“expansion ARR”), or reduce customer losses (“churn”).

The net increase in the ARR is also known as Bookings, or simply how much new business the company has brought in on a net basis.

Bookings = new customer ARR + expansion ARR - churned ARRIdeally, the net increase in the ARR should grow every quarter.

A related metric is the Net Retention Rate (NRR), measuring the company’s ability to retain revenue from existing customers over a specific period of time.

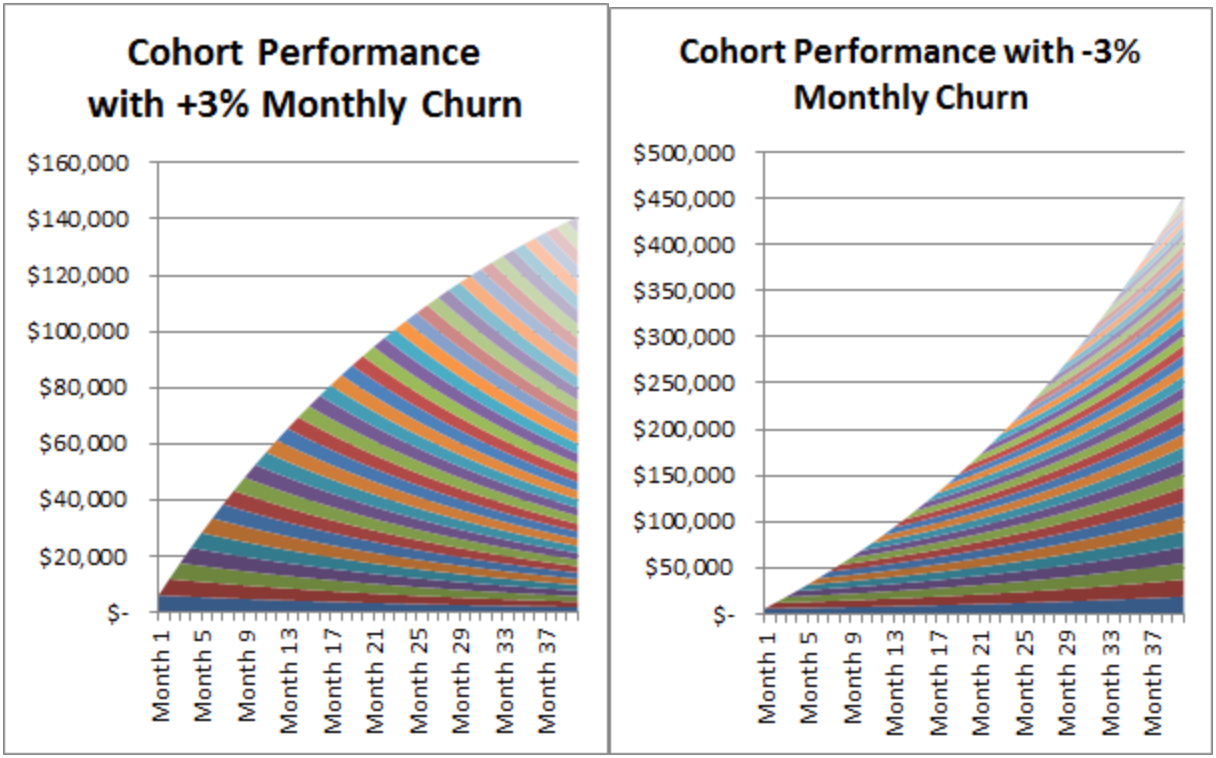

A high churn of a SaaS product is problematic. This means that the service is losing customers at a high rate, and those customers need to be replaced. But if the company can replace those losing customers through up-selling to existing customers, then you’ll get what’s known as negative churn - the holy grail in the SaaS industry.

With negative churn, the company will enjoy an acceleration in revenue growth over time and a parabolic rise in revenues. In other words, each cohort of paying customers will pay more and more. Any new customers will then just add to the total, leading to an acceleration in revenues.

Fellow Substack author Lenny Rachitsky wrote about a study on his Substack, claiming that normal business-to-consumer churn ratios are 3-5% and for business-to-consumer products, 2.5-5.0% for small-to-medium enterprises and 1-2% for large enterprises.

But suppose you find a company with a high churn. What are the explanatory factors for this high churn? There can be a multitude of factors involved. For example:

- The product might not provide value for customers

- The software might be unreliable

- The company may not provide enough customer support

- The switching costs might be too low

- The software might have been sold to the wrong groups of customers

- The customers may have gone out of business

- Or, the company might not be effectively up-selling to existing clients and thus not achieve this holy grail of “negative churn”

The bottom line is this: if a SaaS company can achieve a low churn, its economics will improve materially. SaaS companies with robust revenue retention should be valued highly by the market, and they often are. Once churn is low, monetizing customers more effectively will be the next step.

1.4. Monetizing customers

Many SaaS products use a freemium model, where some features are free to lure customers. Once they see the value in it, they’ll be willing to pay extra for added features.

In other cases, the company employs enterprise sales representatives who take inbound calls from customers or do cold outreach to get customers to pay.

Pricing can be volume-based or feature-based. In the former case, customers can pay extra for higher storage in iCloud, for example, or cross-sell a related product that adds a feature they didn’t know they needed.

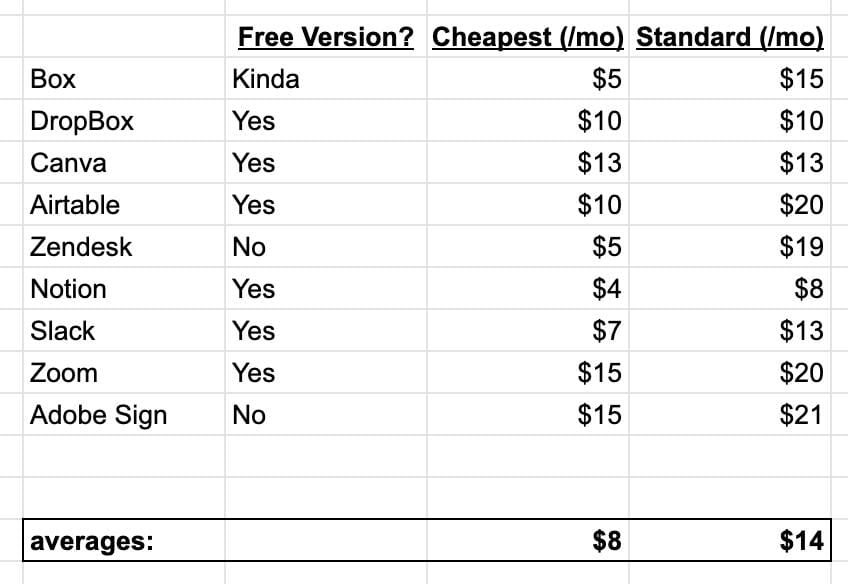

Business-to-consumer products can cost anywhere from $4/month to $20 or even higher. SaaS products sold to enterprises such as Salesforce.com can easily cost $500/month or more.

The problem with the business-to-consumer market is that at $5/month plans, it’s difficult to justify the costs of acquiring customers, either through time spent or through paid channels. It will also be difficult to provide customer support. So, be careful when companies try to survive with low average revenue per user (ARPU). It may simply not be enough to justify the cost of acquiring said users.

There are ways customers can be compelled to pay more. For example, telecom operators are known to make the pricing variable or unique. If it becomes difficult to compare pricing plans with those of competitors, customers may be more willing to pay up - at least on the margin.

2. Stock picking among SaaS names

Over the past week, I’ve read through dozens of write-ups on SaaS companies and found five or so factors that determine the strength of a particular idea. In no particular order, these are best-in-class products, a large total addressable market (TAM), high switching costs, high sales productivity and low valuation multiples.

2.1. Best-in-class product

Engineers talk about finding the perfect product-market fit. But it isn’t easy to quantify. At the end of the day, it’s about a fuzzy concept known as customer love.

One way to find such services is to talk to customers and understand how strongly they feel about the product.

Customer engagement can also be telling. For example, a high ratio between daily active users (DAU) and monthly active users (MAU) tells you that users are compelled to return daily.

Then there’s the question of reputation. You don’t get fired for buying IBM. The same is probably true for many other leading vendors in each vertical. Trust is a valuable commodity, and customers tend to have the greatest trust in the incumbents.

The best products tend to have 90%+ retention rates. Monthly churn should be well below 2%. To the extent the company adds customers, these new customers should have mostly positive reviews. One Japanese website with SaaS reviews is IT Grid Review, a Japanese version of G2 or Trustpilot.

2.2. Large total addressable market

The future revenue of SaaS companies can be seen as a function of:

- The number of addressable customers

- The conversion rate to paid

- The gross profit margin

- Average revenue per user (ARPU)

To get a sense of the addressable market, we can consider the number of individuals or companies that could potentially become buyers. We can also look at the penetration of similar software in other countries. Benchmarking the average cost per user is also helpful to understand the potential upside in the monetization rate. Understanding the potential for cross-selling opportunities once customers become entrenched is also helpful.

2.3. High switching costs

Switching costs for SaaS products tend to be lower than for on-premises software. However, SaaS products sold to enterprise customers are still deeply embedded in customers’ day-to-day workflows. For example, customer information stored on OBIC’s platform is difficult to transfer to another. Much of the software in the enterprise market is also customized to the client’s wishes, even among SaaS offerings. Such high switching costs will provide the vendor with pricing power.

A service with many features built into it will also be difficult to compete with. Upstarts won’t be able to match the value proposition. And once software has been built, it doesn’t require much upkeep. So, with a growing feature set, incumbents can slowly ramp up switching costs.

The software product is often integrated with those of other software vendors. For example, Salesforce’s customer relationship management (CRM) system uses Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) to retrieve data from and send it to the Human Capital Management (HCM) platform Workday.

Compliance with data protection regulations like GDPR and SOC2 can also hinder competition and make switching to other services less likely.

On the other hand, SaaS products tend to have lower switching costs by nature. Switching from one website to another is not difficult. SaaS products in the business-to-consumer area are particularly at risk of churn. However, even for enterprise products, platforms such as AWS may figure out how to make migrations between vendors easier than they are today.

2.4. High sales productivity

In the early stage of a SaaS company’s development, the founder will be the person selling the product. Eventually, he or she will have to hire sales representatives who may or may not exhibit high sales productivity.

You can measure productivity by looking at periodic bookings per sales representative. You might also want to adjust for the how many months of cash is collected up-front. And the cost incurred to reach that sales number.

A related concept is billings, which is the amount of money invoiced in any given period. To get this number, take the revenue in one quarter and add the change in deferred revenue over the quarter, which you can find in the balance sheet. Compare the billings with those for the previous quarter. It’s a better metric than revenue since revenue is a lagging indicator.

Another way to measure sales productivity is through the LTV/CAC ratio. As mentioned earlier, anything above 3x is acceptable. Another way is to look at the number of months it takes to recover the customer acquisition cost, ideally 5-7 months.

Enterprise customers will offer better LTV/CAC ratios than small and medium-sized businesses and individuals. The latter are less likely to spend on premium features, and customer acquisition costs tend to be higher. Churn tends to be higher, too.

2.5. Low valuation multiples

SaaS companies are tricky to value. They incur most of the cost of acquiring a customer directly, including sales, marketing, development, etc. Yet the revenues are recognized over time as the service is used. This creates a mismatch of revenues and expenses, leading to losses in the highest-growth phase of a SaaS company.

Instead, SaaS companies are typically valued as a multiple of their Annualized Recurring Revenues (ARR). Historically, high-growth SaaS companies globally have been valued at around 8x EV/ARR or EV/Sales, as they typically be similar.

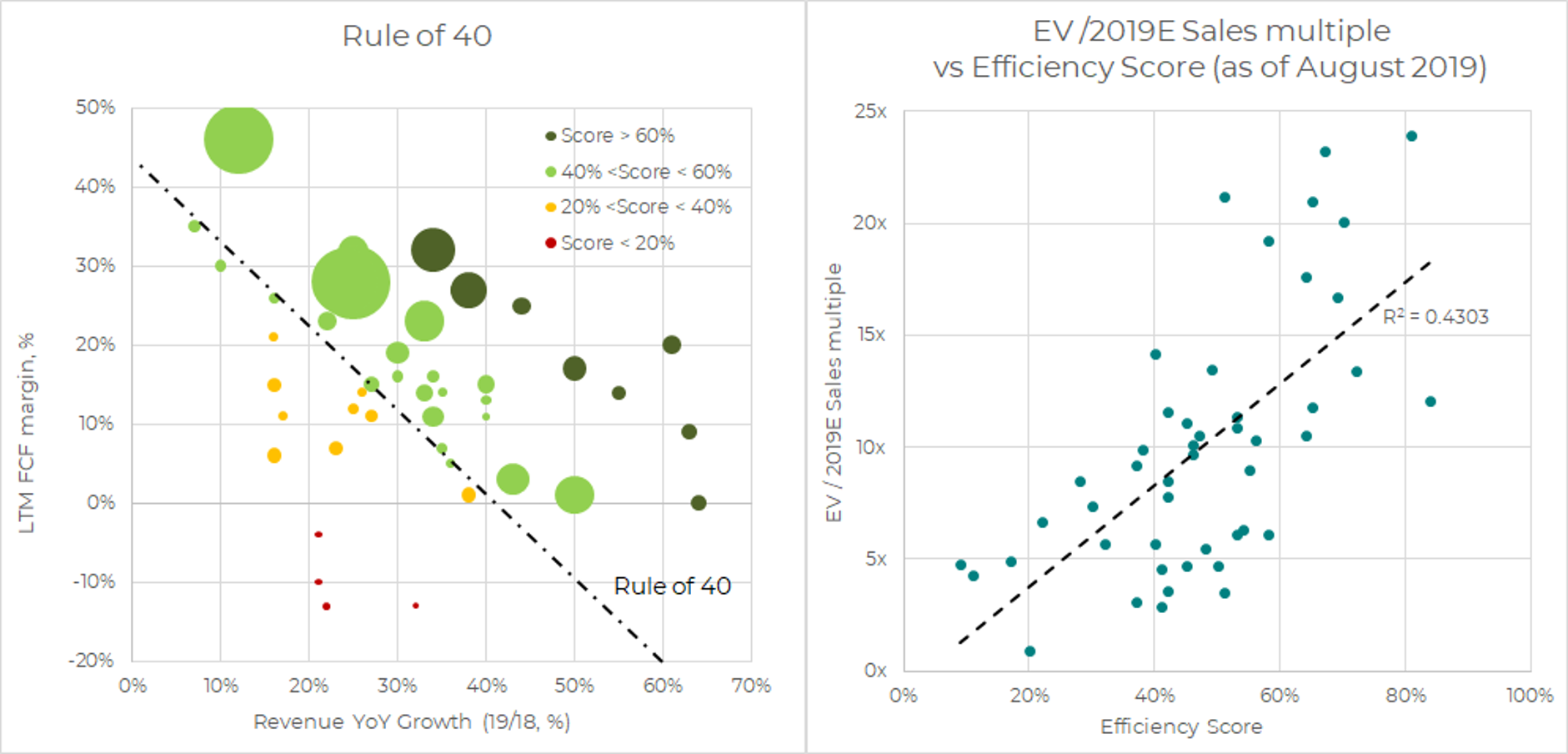

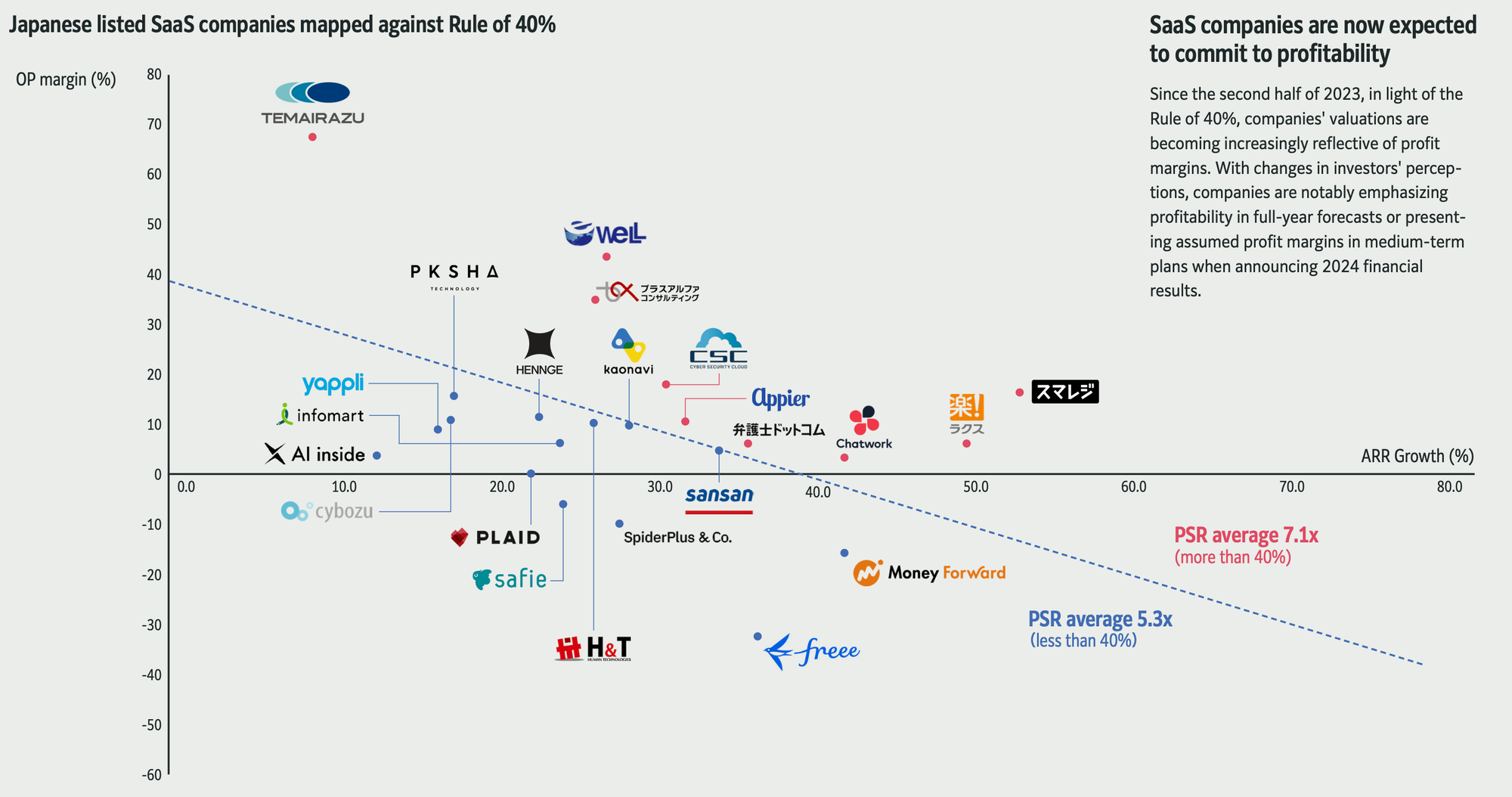

You can also weigh this multiple against a broad metric of quality, known as the Rule of 40. Simply add up 1) the revenue growth rate and 2) the operating profit margin after deducting stock-based compensation. If the sum of these two numbers exceeds 40%, then the company exhibits a healthy balance of growth and profitability. Companies that meet this hurdle yet trade at a low ARR are, hence, worth buying.

You can also look at EV/Sales with customer churn or net retention ratios to understand how sustainable revenues are. If they are sustainable, the company isn’t paying much stock-based compensation and unit economics are strong, we can probably assume that margins will improve over time. It’s difficult to say where margins will end up, though, as the LTV/CAC ratio is not static. So, the value of a particular SaaS company is difficult to pinpoint.

For mature SaaS companies, the calculus becomes much simpler. Just look at them on an EV/EBIT or P/E multiple basis, bearing in mind growth and whether margins have stabilized or not.

3. Trends in Japan’s SaaS industry

3.1. Rising SaaS penetration

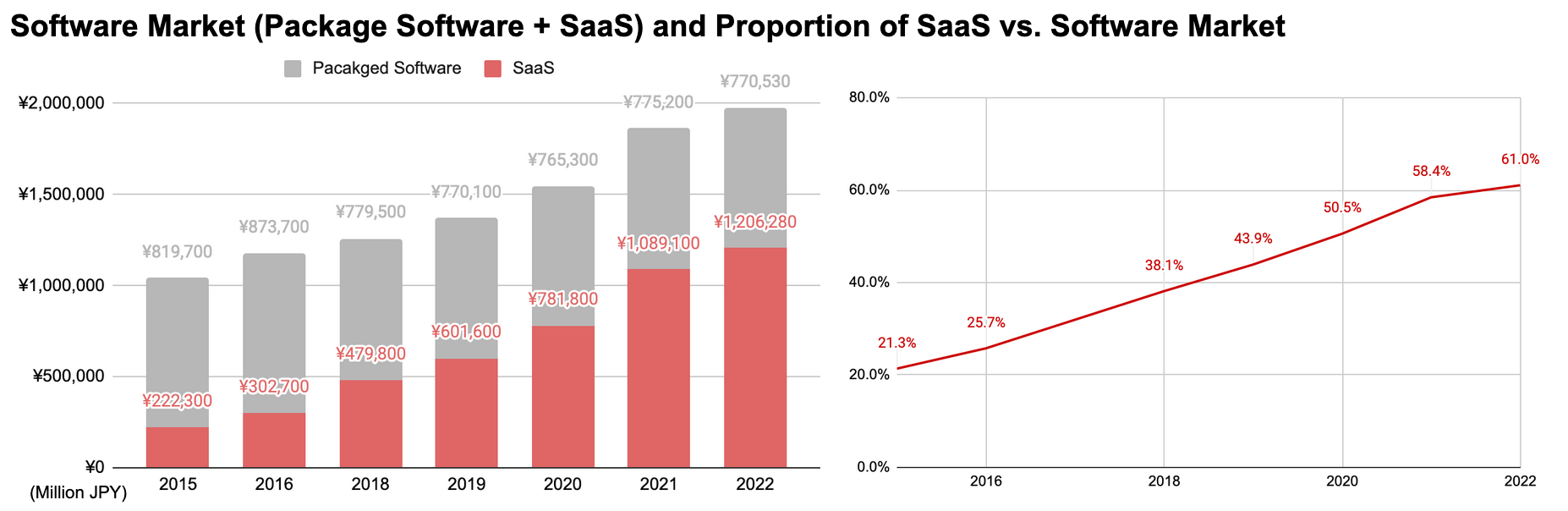

The Japanese SaaS market seems to be growing at an 11% compound annual growth rate, beating expectations a few years ago. The overall software market is clearly moving towards SaaS offerings, with packaged software becoming a thing of the past.

But the upside is even greater than this. Much of Japan’s software is custom-made for specific clients rather than packaged and sold as a product. I’ve seen numbers suggesting that SaaS’s share of total IT spending in Japan remains low at just 5% vs. closer to 20% in the United States.

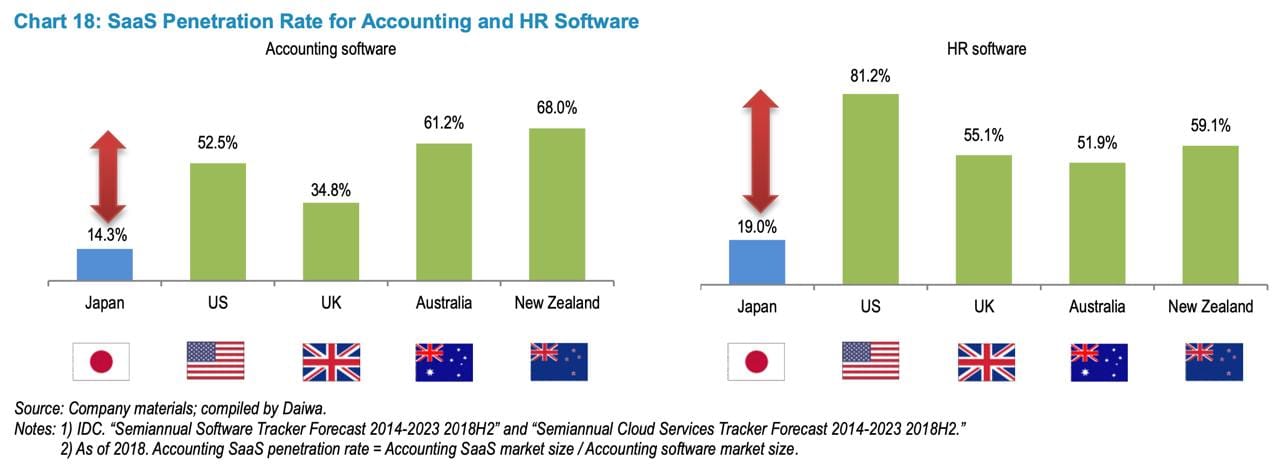

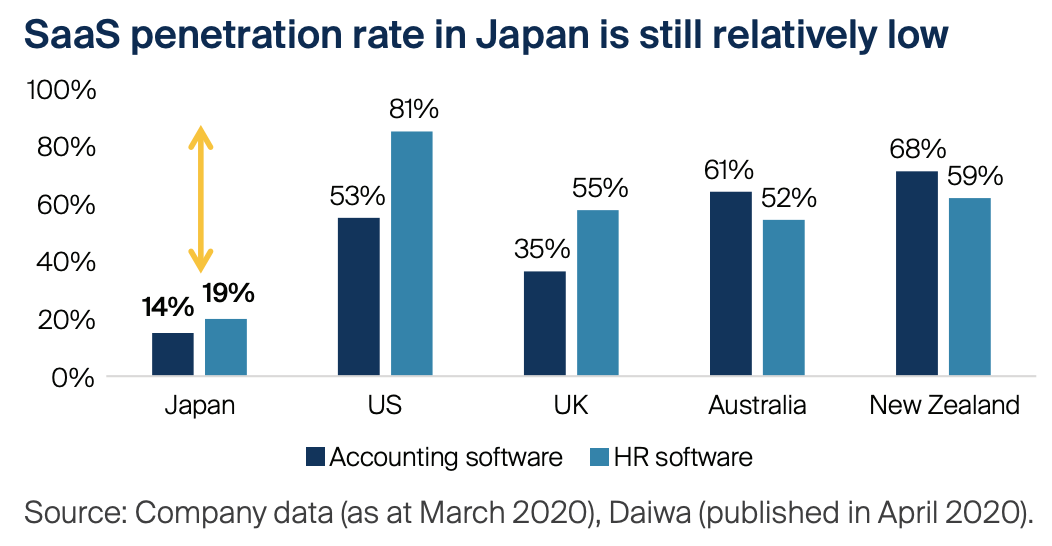

That 4x upside seems to hold true for several sectors. For example, within the accounting and HR software fields, Japan’s SaaS penetration rate is just a quarter of that of the United States.

While these are 2020 numbers, so they are slightly outdated, it’s clear that there is clearly plenty of catch-up potential.

A more recent survey done by Boxil showed that only 34% of Japan’s companies use any SaaS tool. And if they do, they only use 1-10 SaaS tools for their businesses, rather than the 200+ used by most companies globally.

Another study by Okta shows that the number of apps used by Japanese companies is only 35 compared to a global average of 93. So surely, there’s got to be potential for Japan’s SaaS companies to grow.

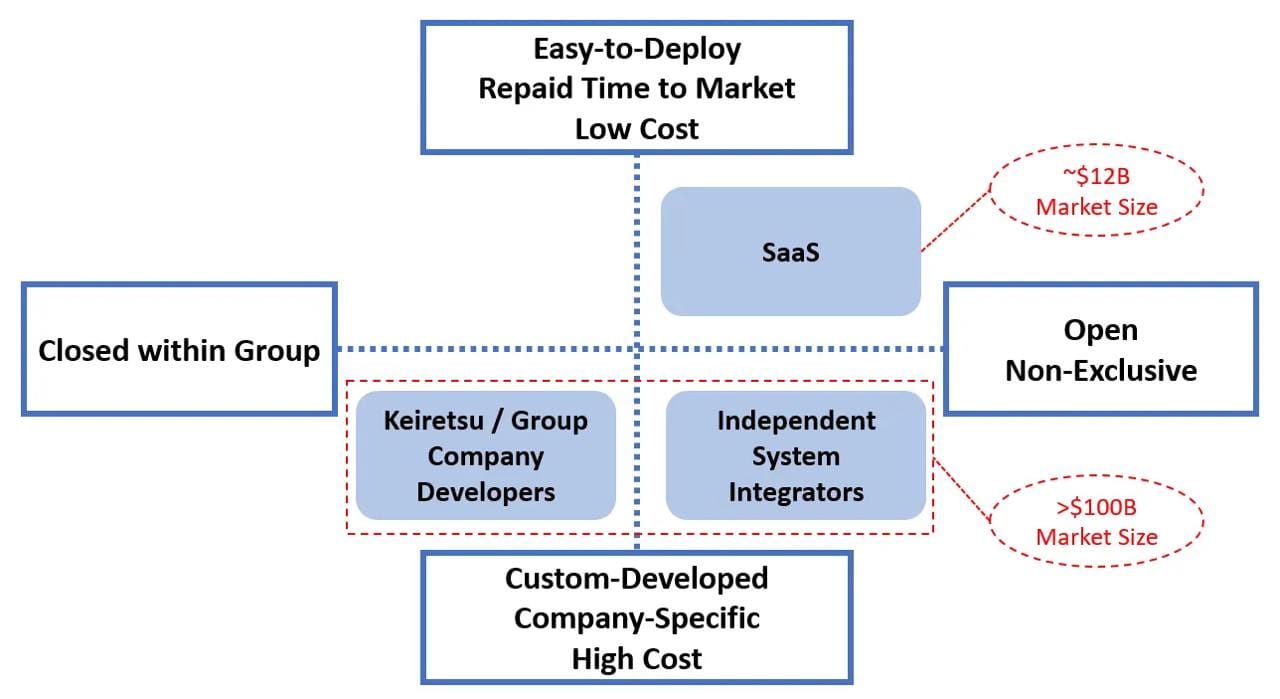

3.2. A shift from on-premise to SaaS

Driving this shift towards SaaS products is a move from on-premise software to cloud services. The Japanese software industry has been slow to change, having been dominated by hardware-centric manufacturing companies that place a low importance on software development. To the extent that SaaS products are developed, they’re often done so internally with sister companies or by system integrators. The software would only be used by a specific keiretsu, with software customized to its needs. The more conventional software developers include Fujitsu, NTT Data and Nomura Research Institute.

Japan doesn’t have much of a venture capital industry, and that’s weighed on software innovation. However, since SaaS doesn’t require much capital investment, younger companies have been able to break through, selling low-priced software to small and medium-sized enterprises. Foreign companies such as Salesforce and Oracle have also broken into the enterprise market. With the clear benefits of SaaS, including low up-front cost, scalability, accessibility and continuous support, the industry will continue to shift away from on-premise software, though perhaps at a slow pace.

3.3. The government’s digitalization push

In 2021, the Japanese government established its Digital Agency. It was a push by then-prime minister Fumio Kishida to accelerate the digitalization of government services. One such initiative is the GovCloud. Each government agency will replace its current software vendors with a cloud computing platforms such as Amazon Web Services, and then let other government agencies build applications on top of this. Many government processes remain manual but should migrate to digital soon, benefitting certain SaaS vendors in the process.

In 2023, Japan’s Information Technology Promotion Agency wrote a digital transformation (DX) whitepaper showing that Japan lags behind the United States. The number of companies in Japan with 100-300 employees with digital transformation teams is only 68% compared to 90% in the United States. So digital transformation hasn’t been a priority among companies either, and the government is trying to address this problem.

One measure is Japan’s new Startup Visa program, focused on attracting innovative companies to Japan. And attracting foreign entrepreneurs who want to build start-ups in the country.

3.4. The rise of Vertical SaaS

Another key trend is the rise of vertical SaaS products addressing issues relating to specific industries. We’ve products tailor-made for the construction industry, logistics, manufacturing, the hospitality industry, etc.

Among Japan’s venture capital backed SaaS companies, there are only about 100 to 150 vertical SaaS businesses today. In the listed universe, examples of vertical SaaS companies include Temairazu for the hospitality industry and CYND for beauty salons. Though the fastest growing vertical SaaS companies appear to the medical and the logistics industries.

3.5. Outsourcing to Vietnam and elsewhere

Another key trend has been to shift software development offshore, including to Vietnam and India. American-listed software company Zoom has become famous for employing most of its engineers within mainland China. However, even in Japan, several publicly listed SaaS companies such as Raksul, Money Forward, and Cybozu have all located a portion of their employees abroad.

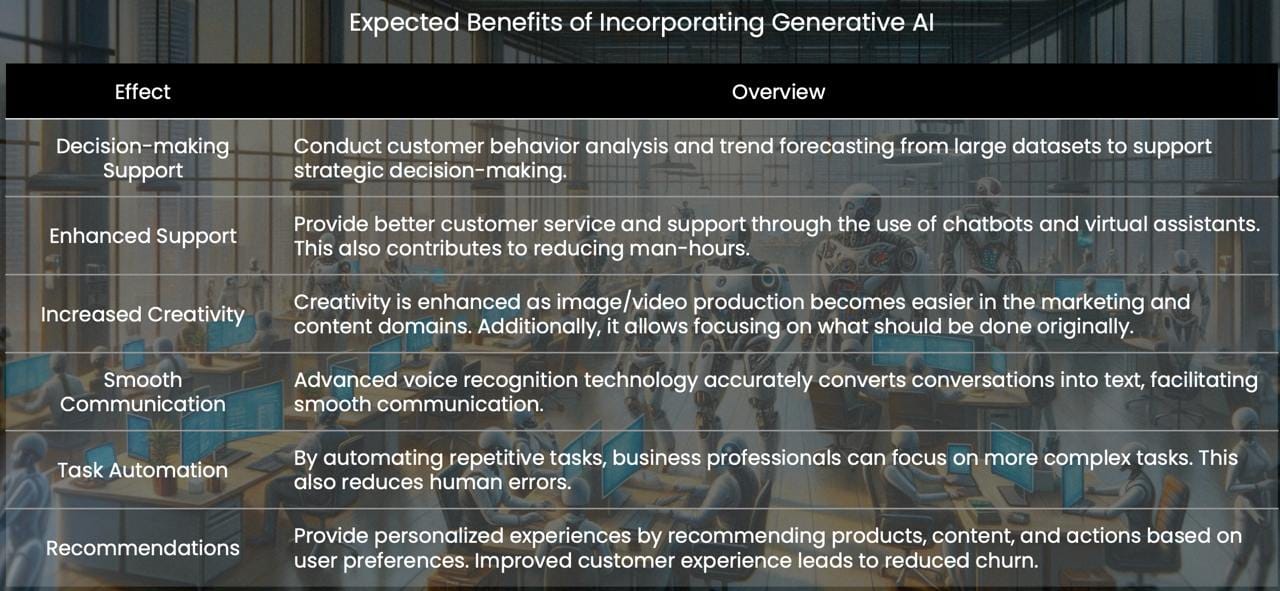

3.6. Disruption from generative AI tools

Finally, there’s an open question of whether generative AI tools and large language models will disrupt some of the current software vendors. Presumably, the ease of developing new software should devalue existing offerings.

So far, the AI native companies that have emerged have focused primarily on customer support services, chat and marketing tools.

Other use cases of generative AI tools include:

- Improved algorithms to provide personalized recommendations based on user preferences.

- Greater ease in creating AI-generated images, which should impact services such as image data banks

- Automation of repetitive tasks, perhaps within the accounting field.

These are the sectors that I would consider to be ripe for disruption.

4. The investable universe of stocks

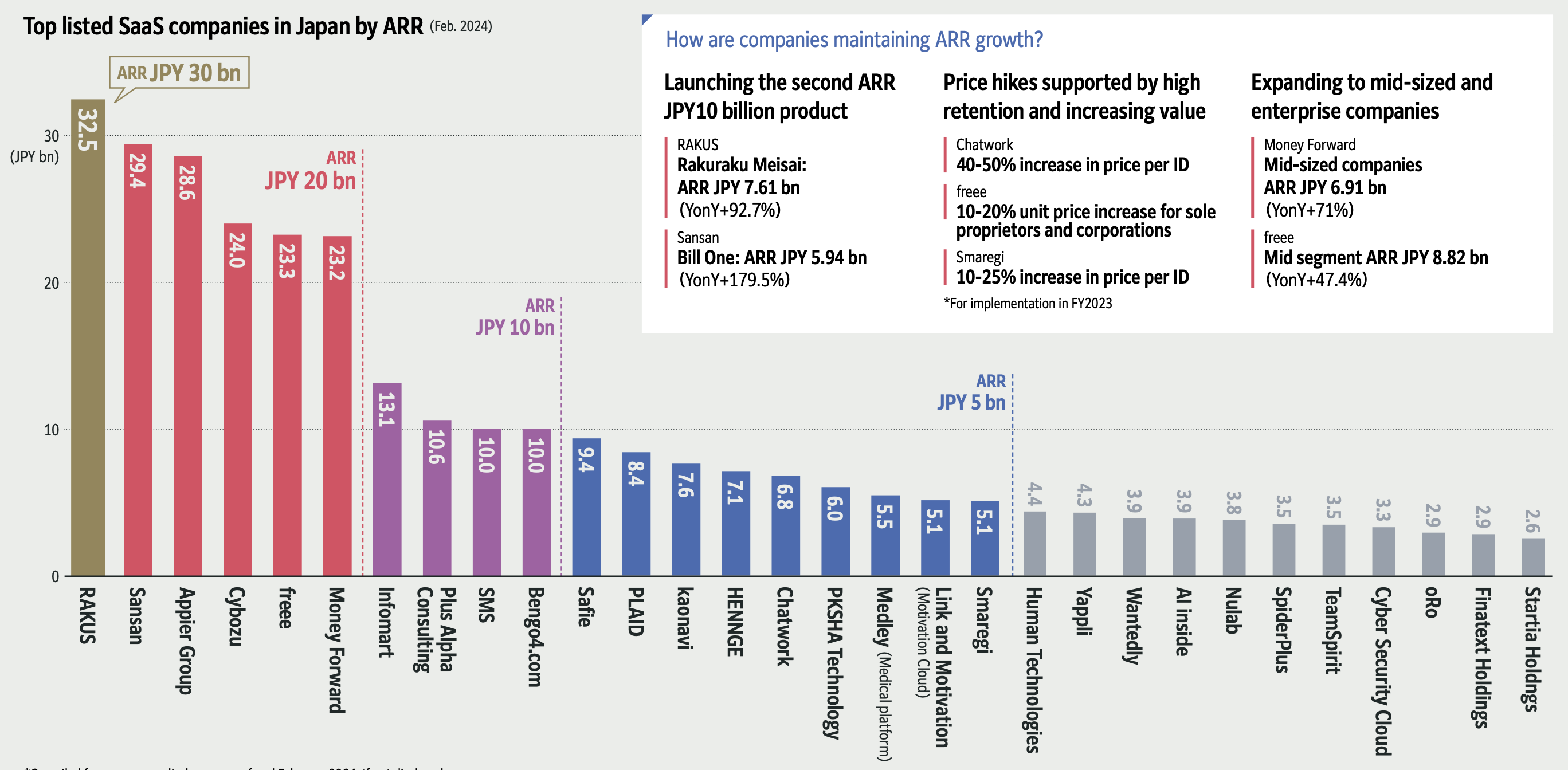

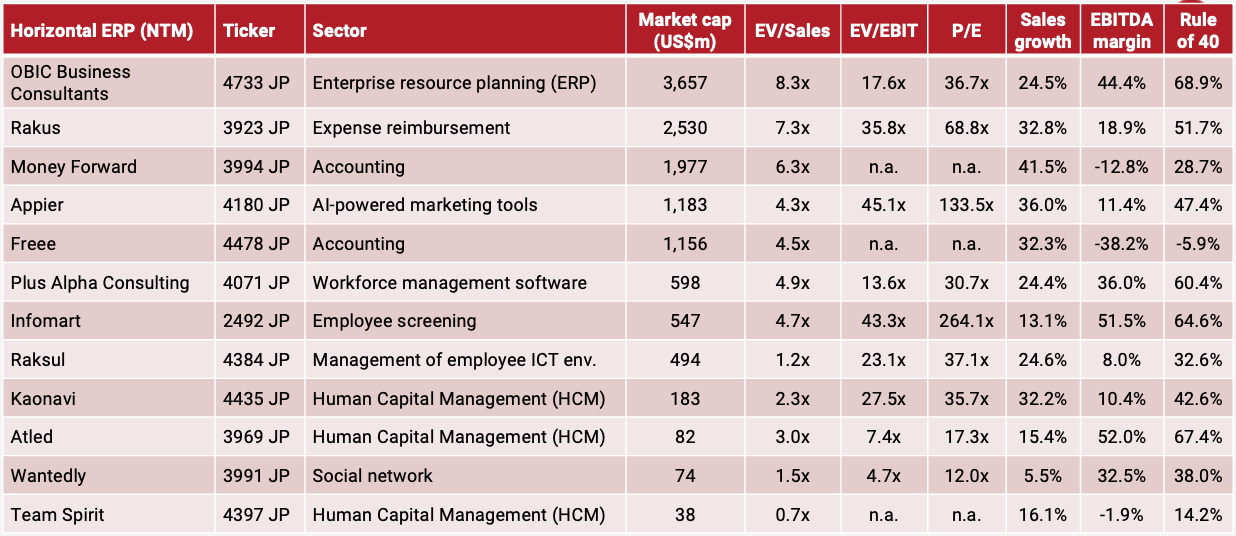

Japan’s listed SaaS companies enjoyed a COVID-19 bump in ARR growth. Since then, we’ve seen a normalization of demand. And consequently, SaaS multiples have come down to more palatable levels. The average EV/Sales is now well below 10x and frequently below 5x. You could argue that there’s finally value in the sector.

Japan’s largest SaaS companies by annual recurring revenue include Rakus, Sansan, Appier, Cybozu, freee and Money Forward. In other words, the list is dominated by horizontal ERP companies, including accounting software providers.

In terms of the Rule of 40, the ones that score best are hospitality booking system providers Temaizaru, Rakus and Chatwork (kubell). But bear in mind that sales growth can be volatile. And the latest sales growth numbers tend to be priced-in, anyway.

To understand the investable universe of SaaS stocks, I’ve divided them into four categories: horizontal enterprise resource planning (ERP) companies, vertical ERP companies focusing on specific industries, collaboration tools, and finally, data services providers. There may be better ways to partition the universe, but it’s a good start.

4.1. Horizontal ERP

Japan’s largest enterprise resource planning (ERP) company is OBIC, which provides customized software solutions to its customers. OBIC’s separately listed subsidiary OBIC Business Consultants (4733 JP - US$3.7 billion) is more focused on customized solutions for customers as well as cloud services. OBIC has a product called Kanjo Bugyo, which has a top market share among ERP software in Japan. The SaaS version is called Bugyo Cloud, but so far, only a small portion of its customers have completed their migration to the SaaS offering.

Rakus (3923 JP - US$2.5 billion) has the leading market share in several niche applications, such as expense settlement and digital invoicing systems. Other companies within the business spend management industry are SAP’s Concur and Panasonic subsidiary EasySoft. There’s a clear risk that others, such as accounting software providers Money Forward and freee, will enter the field eventually, too. Rakus’s software has middling IT Grid Review scores. And the stock trades at a relatively elevated 7.3x EV/Sales.

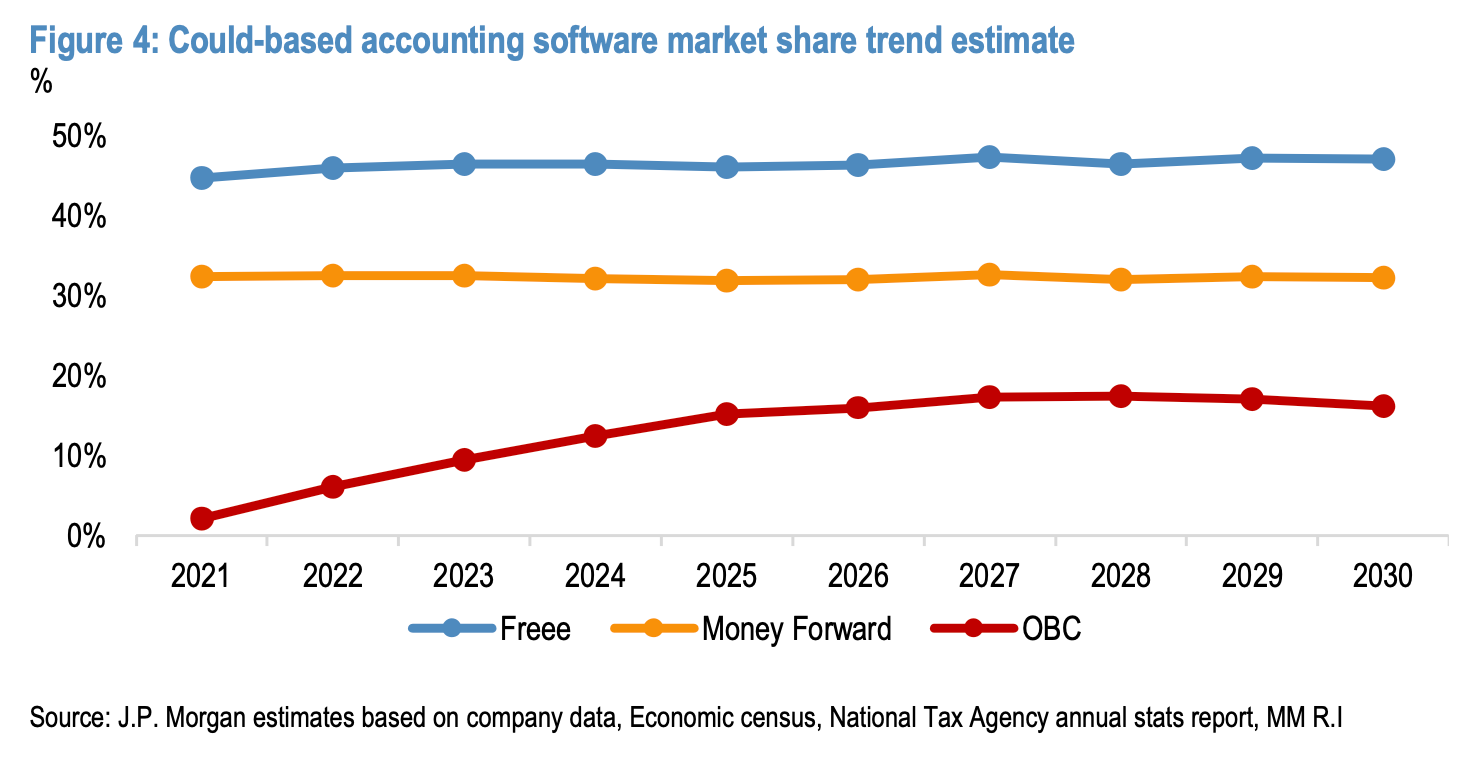

The story with accounting software developer freee (4478 JP - US$1.2 billion) is more exciting. You can think of it as the Japanese version of Xero, a New Zealand accounting software developer that’s been a 30-bagger since its IPO in 2012. Today, freee has annual recurring revenues of JPY 26 billion (US$172 million) and 532,000 customers. The monthly churn rate is currently 1.2% but 0.6% for its 200,000 corporate customers. The total addressable market is close to 7.0 million businesses, including self-employed individuals. The fees are around JPY 24,000/year (US$159/year) for self-employed individuals and much higher for corporates, with an ARPU of about JPY 50,000/year (US$330/year). These prices seem reasonable, though I wonder how much further upside there is. The stock now trades at an EV/Sales of 4.5x. Can freee’s revenues reach JPY 170 billion, giving it an EV/Sales of 1.0x with Xero-like margins of 15%? It’s plausible. However, bear in mind that Freee has diluted shareholders by 7% per year in the past few years through equity issuance and stock compensation.

Competitor Money Forward (3994 JP - US$2.0 billion) is said to have an inferior product to free though its product Money Forward ME (マネーフォワード) actually has a similar IT Grid Review score to freee’s. It’s also marginally more profitable, with an EBITDA margin of -13%. I don’t see either freee or Money Forward as necessarily trading at the wrong valuations.

Appier (4180 JP - US$1.2 billion) is listed in Japan but is actually a Taiwanese company. It uses generative AI tools to help businesses identify potential customers. Its software is designed to improve customer engagement and drive marketing ROI higher. I have no idea whether its product is effective or not.

Within the human resource management industry, competition appears to be cutthroat. One such company is Plus Alpha Consulting (4071 JP - US$598 million) (“PAC”), which offers a product called Talent Palette that helps the HR department keep track of work hours, payroll and work history. It has a 4.0 score on IT Grid Review. The yearly churn rate is only 5.8%. The software apparently has 4,700 features, which should keep competition at bay. Key competitors include Visional (not a pure-play), Kaonavi, Freee and Money Forward. There should also be switching costs after employee data is stored in the Talent Palette database. The software is apparently strong in analyzing unstructured data, used, for example, in identifying motivated employees, though there is a risk that this feature becomes commoditized by the rise of generative AI tools. The ARPU is currently JPY 400,000 or about US$2,665. That ARPU seems high to me. The fact that it doesn’t provide stock compensation is a major plus in my mind. The stock trades at 4.9x EV/Sales, 13.6x EV/EBIT and 30.7x P/E, with revenues doubling in the last three years. It looks compelling. There’s a great recent write-up on the stock here.

Competitor Kaonavi (4435 JP - US$183 million) has a similar product with a worse score on IT Review and recent deceleration in top-line growth due to competition Visional, Freee and Money Forward. The annualized churn rate has been 7%, slightly higher than Talent Palette’s. There could be an upside in the ARPU of just JPY 187,000/year or about US$1,240/year. The stock also trades cheaply at just 2.3x EV/Revenues despite a respectable Rule of 40 score of 43%. The following VIC post here argued that Kaonavi has “verifiably attractive unit economics”. No significant stock compensation either. If the VIC poster is correct that we could be seeing a 30% operating margin on the horizon, the stock looks very cheap indeed. Would just need to become comfortable with the quality of the product.

Raksul (4384 JP - US$494 million) is somewhat of a conglomerate. Its main business is providing a platform for outsourced business printing services. Raksul also owns a transportation brokerage service called Hacobell. And finally, it owns a SaaS company called Josys, which helps companies keep track of company IT resources, including both licenses and devices. Josys doesn’t seem fully owned, but Raksul will have the opportunity to buy out minorities at some point. Does the product have a moat? Unclear. In Richard Katz’s new book, he mentions Raksul as an innovative company. You can find a VIC write-up on the company here and an interview with CEO Yasukane Matsumoto here. The stock does look cheap at 1.2x EV/Sales, but I’d have to do more research to understand whether the business printing service segment is on a decline or not.

Infomart (2492 JP - US$547 million) is a provider of an online platform that connects restaurants with wholesalers. They pay a monthly fee for access to the platform, with no further transaction costs. Growth has been tepid, and margins have contracted, with weaker gross margins and higher promotional expenses. You can find a write-up at Shared Research’s website here. But I’m not keen to dig deeper.

Substack Made in Japan wrote about Atled (3969 JP - US$82 million) earlier this year here. He made the case that Atled’s workflow management software products “X-point” and “Agile Works” dominate this particular niche. Processes that can be handled by the software include claims, purchase agreements and requests for time off. Employees can then track the progress and see the documentation submitted for each project until approval. IT Grid Reviews for X-point Cloud and AgileWorks are both 3.9. The monthly churn is incredibly low at just 0.14% per month and that clearly bodes well for earnings sustainability. From that perspective, an EV/Sales of 3.0, EV/EBIT of 7.4x and P/E of 17.3x look attractive. The company is growing in the double digits, though it does seem like a low-value-added product to me.

Wantedly has a business social networking platform with the same name, apparently with 2 million individual users and 30,000 corporate users. It matches candidates and employers based on the employer’s vision and values. It makes money through a fixed monthly fee for corporate users and advertising revenues on top. The product has a 3.8 score on IT Grid Review, with employers saying that you can hire people who fit your corporate culture. Seems like a niche service. The stock is cheap at P/E 12.0x, but sales growth appears to be tepid.

Finally, Teamspirit (4397 JP - US$38 million) offers a software product for attendance management, replacing the age-old process of employees checking in and out with time cards. It also offers an expense approval and reporting feature. It’s had strength in small- and medium-sized businesses and is now refocusing its attention on larger enterprise customers. The founder has just stepped back. The stock does look cheap at 0.7x EV/Sales but is not profitable. The product has a 3.8 score on IT Grid Review. You can find a nice write-up on TeamSpirit at Japan Business Insights here.

Overall, in this segment I’m most excited about Plus Alpha Consulting and Kaonavi, as their software should be deeply integrated with customer workflows. They’ve been good to shareholders. And their valuations look compelling, too.

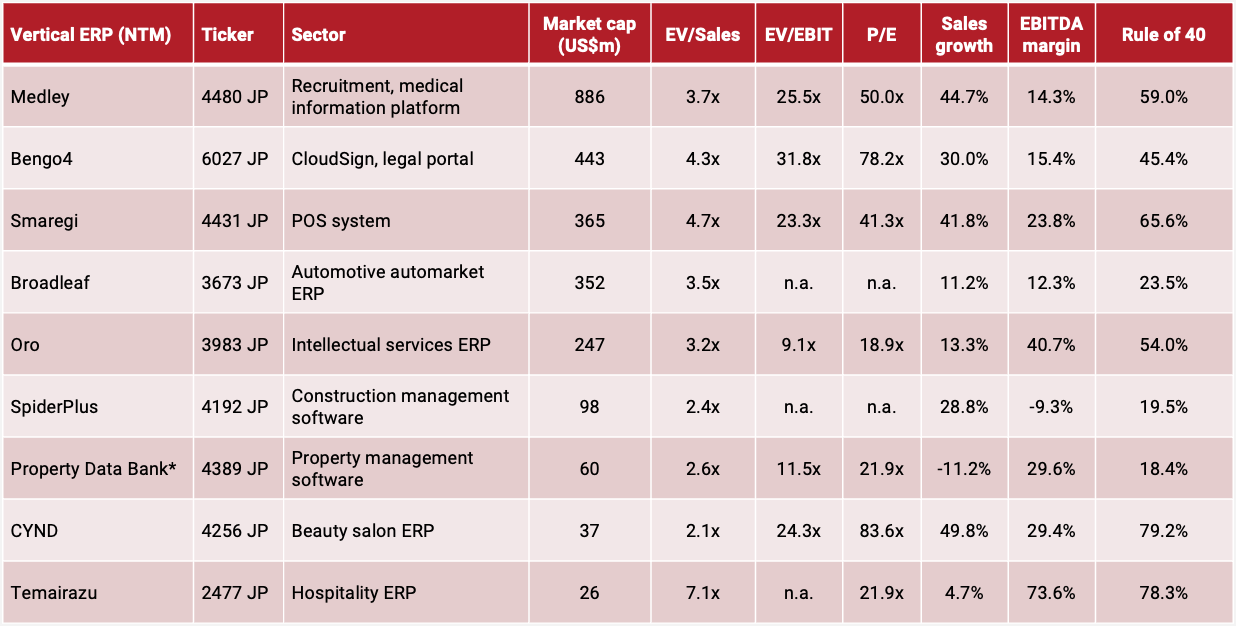

4.2. Vertical ERP

Vertical enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems help companies in manage business processes such as accounting, logistics, payroll, customer relationships, etc. These differ from say SAP in that they only target companies within verticals such as the hospitality industry or the healthcare industry.

The largest such vertical ERP developer is Medley (4480 JP - US$886 million). It has two main services: a job matching website called JobMedley, as well as a SaaS ERP product called Medical PF, targeting hospitals, clinics, pharmacies and dentist offices. Medical PF’s revenues seem to be growing rapidly - almost doubling year-on-year. It’s on the verge of becoming cash flow positive. Some of Medical PF’s features include telemedicine, an electronic medical record system, a pharmacy support system and an online medical encyclopaedia. The stock based compensation is only about 1% of sales per year and fully expensed. An EV/Sales multiple of 3.7x doesn’t seem high at all given how explosive Medley’s growth has been. There’s a great write-up on Medley at Jake Barfield’s Substack here.

Bengo4 (6027 JP - US$443 million) has several key business areas, too. It owns a platform called Bengo4, a platform that connects consumers to lawyers with 11 million monthly users. It has a similar platform for tax accountants. It also has a legal affairs portal with information sold to the 58,000 lawyer members. Finally, it offers a SaaS product called CloudSign, which allows users to electronically sign documents. I don’t understand why signing can’t take place through Adobe Acrobat or similar software. However, the IT Grid Review score is 4.3, so customers clearly think otherwise. The EV/Sales of 4.3x, EV/EBIT of 31.8x and P/E of 78.2x means the stock is priced for growth. A nice little write-up on Bengo4 can be found at Nippon Nuggets here.

Smaregi (4431 JP - US$365 million) offers a Points of Sales (POS) system sold to retailers. It helps manage cash registers, inventory, customer relationships, and reservations. Users can also help analyze transaction data through visualizations. There are apparently 45,000 stores using the Smaregi POS system. It has also created an app ecosystem called the Smaregi App Market to improve the feature offering. The Smaregi IT Grid Review score is a whopping 4.3 stars. It can handle QR payments and credit cards. Growth has been explosive, and the operating margins have remained positive throughout. With ~40%+ revenue growth, who knows what the right multiple is? I haven’t found a good write-up on the stock, but I’m excited and want to dig deeper.

Then we get to Japanese auto aftermarket software company Broadleaf (3673 JP - US$352 million). Its customers are auto maintenance shops. It has an auto parts inventory database as well as an online marketplace that connects buyers and sellers. Over half of the revenues come from license fees for the use of its software. It’s been transitioning to a SaaS pricing model, but I’m not sure how far it’s come in this transition. I’m skeptical about the product, and indeed, revenues have fallen in the past few years. Japan Business Insights wrote about Broadleaf here.

A company that’s more of a pure-play SaaS company is oRo (3983 JP - US$247 million). It’s a provider of a SaaS ERP system called ZAC, which is designed for industries that manage business on a case-by-case basis: IT services, advertising, public relations, content production, consulting, etc. It used to offer one-off purchase options but has now completely transitioned to a SaaS fee structure. It recently launched a new SaaS management tool called dxeco, which it has high hopes for, helping to track subscriptions within each company. oRo also wants to expand internationally. The EV/Sales of 3.2x seems low, but the low sales growth suggests an underlying issue. The ZAC score on IT Grid Review is only 3.2. There’s a great recent VIC write-up on oRo here, but it might be leaning too bullish.

SpiderPlus (3983 JP - US$247 million) is another vertical SaaS focusing on the construction industry. Its software helps construction companies manage projects, with site drawings, construction photographs, and inspection records all stored online and accessible through any device. A few years ago, it only had about 1,000 clients, so it does seem like a small business. But it was growing rapidly. The standard version only costs JPY 3,000/month (US$20/month), which seems minimal. The EV/Sales is only 2.4x, but the company is making losses, the cash flow is negative, and it is growing relatively slowly. It doesn’t have any reviews on IT Grid Review. There’s a write-up on Nippon Nuggets here from 2021, back when SpiderPlus used to trade at heady levels.

Another vertical SaaS is Property Data Bank (3983 JP - US$247 million), which was covered by Made in Japan here. The software is used by commercial property landlords to manage their assets. For example, its customers might be J-REITs or large corporations such as Japanese railway operators. Part of the revenues are non-recurring and part subscriptions. It’s been profitable almost from the beginning and remains so. It’s also worrying to see revenues decline so early in its development, though Made in Japan makes the case that it’s due to delayed orders and delayed revenue recognition. If so, the stock could be cheap-ish at 2.6x EV/Sales. I haven’t been able to find any reviews for its products, so my conviction in the product is low.

CYND (4256 JP - US$37 million) is a vertical SaaS product focusing on the beauty industry. It provides reservation management software with an estimated 3% market share in Japan. It acquired its second-largest competitor, Pacific Porter, in January 2023. The ARPU per store is currently JPY 109,000/year, equivalent to US$722/year. I am not sure whether there’s an upside in this number. However, there could be an upside from their 15,000 contracted stores to the addressable market of 550,000. The two founders seem to understand capital allocation and are advised by Sun Mountain. CYND’s key product, Beauty Merit, has 4.5 stars at IT Grid Review. There’s an amazing write-up on CYND here. At 2.1x EV/Sales, it seems like a steal.

A more mature business is Temairazu (4256 JP - US$37 million). A recent VIC write-up on Temairazu can be found here. Like CYND, it provides a booking service for hotel rooms, helping them manage room inventories effectively across different sales channels. In other words, it’s a middleman between a multitude of booking websites and a large number of hotels. Surprisingly, Temairazu saw revenues almost flat during COVID-19, but thanks to the weak yen, they’ve now begun growing again. There’s no feedback on IT Grid Review. The stock has an EV/Sales of 7.1x, which can be justified thanks to a whopping 74% EBITDA margin, giving it a P/E of 21.9x.

I’m finding a great number of companies to be excited about here. For example, Medley is showing explosive growth and occupies a niche for itself. Smaregi’s POS system has an incredible score on IT Grid Review and is exhibiting explosive top-line growth of 40%+. I’m perhaps even more excited by CYND, which only has a 3% market share in Japan, with plenty of whitespace for further growth and an EV/Sales multiple of just 2.1x.

4.3. Collaboration software

Collaboration software falls outside the realm of enterprise resource planning services, and hence I put them in a separate category. Such software can be likened to Slack or perhaps Microsoft Teams.

For example, Cybozu (4256 JP - US$675 million) has a product called Kintone that helps teams manage their workflows and communicate in one place. There’s also a no-code feature that helps users create web apps. There’s another product called Cybozu Office that offers email, scheduling and document management. There’s also a groupware product called Garoon that facilitates collaboration across teams across different projects. These have IT Grid Review scores of 3.7-3.8. Kintone has become a major success, but overall, the company doesn’t meet the Rule of 40 hurdle. An EV/Sales of 3.1x is not high but in line with the peer group.

kubell (4448 JP - US$129 million) is a business communication app that sounds like it’s similar to Slack. It offers chat, task management, file sharing, video calls and contact management features. The IT Grid Review score of 3.8 is just okay, with reviewers commenting that it’s easy to use, allowing for quick communication. I doubt that it’s more convenient than Google’s G Suite or Slack, however. kubell is not profitable, though it is now cash flow positive. The EV/Sales multiple of 2.4x doesn’t seem excessive. There’s a quick introduction to kubell (formerly Chatwork) at the Nippon Nuggets Substack here.

Finally, Nulab (5033 JP - US$34 million) is yet another SaaS collaboration tool with 4 million users globally. Its flagship product is called Backlog - a project management tool targeted to software development firms. It has task management, version control, and bug tracking features. The website and software look slick, and I’m surprised they’ve grown successfully overseas. The IT Grid Review score of 3.9 is average, but users seem satisfied, especially when organizing multiple projects simultaneously. Nulab also has an ID management tool. Top-line growth ranged from 16% to 35% in the past few years, and the company is now profitable with a P/E of 14.8x. Seems like a complete steal to me - I wonder if there is more to the story.

Out of the three, I’m certainly most attracted to Nulab, with its explosive sales growth and low valuation multiples. But there’s probably a key investor concern that I haven’t yet identified.

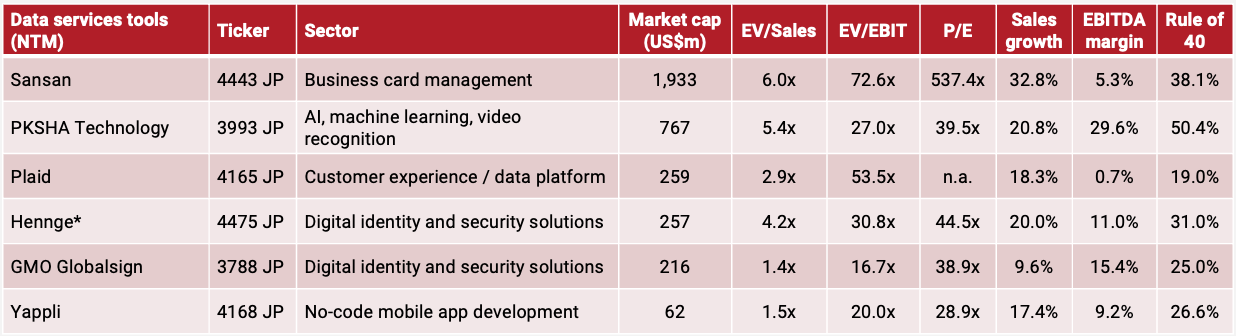

4.4. Data services tools

We’re now getting to the final section of this post: data analytics, data processing tools, cyber security software, authentication software, etc. Essentially software falling into the “other segment”.

For example, Sansan (4443 JP - US$1.9 billion) is Japan’s leading platform for scanning and exchanging business cards. I didn’t even know this was a business, but the Japanese seem to take the exchanging of business cards seriously. In 2021, almost 3 million people had downloaded the Sansan app and registered their business cards with the platform. Sansan also connects with Salesforce, making it possible to find contact details through the Salesforce platform. I still think it’s an odd business ripe for disruption, and at 6.0x EV/Sales, I’m not interested in getting involved. The Nippon Nuggets Substack wrote about Sansan back in 2021 here.

PKSHA Technology (3993 JP - US$767 million) specializes in natural language processing, image recognition and machine learning. It’s a bit fuzzy exactly how they help their clients, but it seems like they tailor-make algorithms for clients, for example, by constructing AI chatbots, voice bots, etc. It then gets paid subscription fees for the services throughout the utilization of its software. Sounds like PKSHA could either benefit from generative AI tools or be at risk for disruption. Above my pay grade, without a doubt.

Plaid (4165 JP - US$259 million) - not to be confused with the American fintech company with the same name - offers a digital marketing service under the Karte brand name. These provide website analytics and segmentation of website visitors. Back in 2021, Plaid had over 500 corporate customers paying Plaid to track their websites. The product helps clients understand customers' behaviour better, though I’m sure Google Analytics can provide similar services for free. It also helps display personalized content for each website visitor, boosting sales and retention, especially for e-commerce websites. The product has a 4.1 score in IT Grid Review. The company remains loss-making and cash flow negative with modest share count dilution. There’s a Nippon Nuggets write-up on the stock here.

Hennge’s (4475 JP - US$257 million) software product Hennge One allows organizations to access multiple cloud services with a single set of credentials. This should help simplify user management. It offers multi-factor authentication and IP restrictions. It also offers an email security solution. In essence, it’s a proxy for the growth of cloud services in Japan, with cloud adoption still far behind most other developed markets. I’m still not sure how strong Hennge’s moat is, however, with the value-add from the software seemingly limited. Nippon Nuggets wrote about Hennge as well, and the write-up is available here.

GMO Globalsign (3788 JP - US$216 million) is an identity and security solutions company, part of the broader GMO Internet Group. It seems like the key benefit of GlobalSign is that it facilitates digital signatures. It doesn’t meet the hurdle of the Rule of 40. I’m not sure how much of a moat it has, and I don’t find the valuation particularly appealing either.

Finally, Yappli (4168 JP - US$62 million) is a no-code platform that helps companies build mobile apps easily. Clients include blue chip companies such as Toyota, Kyocera, Fujitsu, Yamaha, etc. Apparently, in 2021, the LTV/CAC ratio was 5x, suggesting that growth remained profitable at that time. Nippon Nuggets, who wrote about the company here argues that it’s comparable to WIX but for mobile apps. Growth has decelerated, and the company remains negative cash flow. Customer reviews on IT Grid Review are poor at 3.5.

Neither of these companies is understandable for a generalist like me, and I therefore prefer to stay away.

Conclusion

I’ve been cautious about technology companies in the past. Fundamentals can change quickly, and switching costs are often low. SaaS companies deserve greater attention because revenues are recurring and frequently growing rapidly. The best SaaS businesses can enjoy incredible margins at scale. And while precision may not be attainable, the considerable upside for some of them can probably justify the risk.

The companies I’m most excited about are human capital management software developers Plus Alpha Consulting and Kaonavi, as they should enjoy switching costs. Given their growth, Medley and CYND seem to trade at low valuations in the vertical SaaS industry. Finally, both Smaregi and Nulab offer compelling services with significant potential for growth. Expect much more on the Japanese SaaS industry here on Asian Century Stocks in the future.